There is a remarkable absence of barriers between you and anything you come across. The hypnotic, breathtaking dances and frantic contortions of a mask festival, for example, are not put on for the benefit of visitors – they exist for the village, and the ancestors.

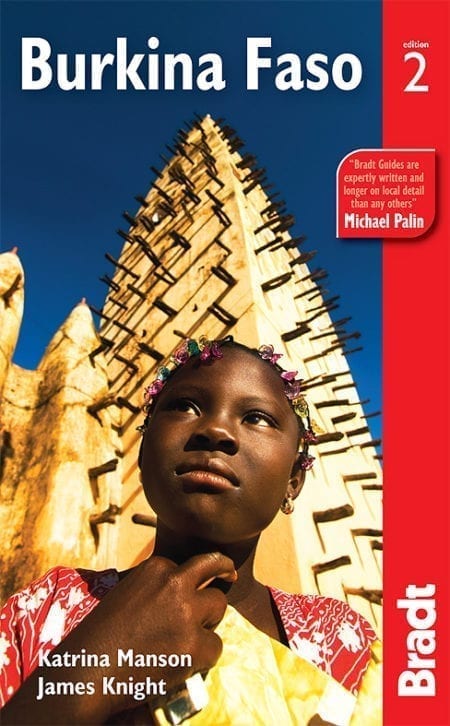

Katrina Manson & James Knight, authors of Burkina Faso: the Bradt Guide

We arrived in Burkina Faso with enough French to order a sandwich but not much else, and somehow found a place to stay within three days. Within no time, we made friends with some guys from the area – which was at one time legendary for its skilled horseback riders (Burkina Faso is obsessed with stallions) – who helped us spruce the place up, devour delicious grilled garlic chicken, and swing tea with hot coals at full arm’s length in the empty living room.

But the best was yet to come. Living in the capital Ouagadougou (Ouaga) was a wonderworld of open-air cinema, live music in late-night bars and the thrill of pleasanterie – teasing banter that makes immediate friends of strangers. Leaving the capital took us deep into the unknown – tracking lions in the east, watching bronzemakers and leatherworkers at work in the central belt, and disappearing into thousand-year-old ruins in the far northern sands of Bani, where blues guitar mingled with the starry night. The lush green habitat of elephants and brightly painted, booby-trapped homes in the south was the final revelation.

And then of course there were the festivals in this richly cultured country, which seemed to take place every other week. Highlights included watching synchronised equine dancing in the northeastern land of historic warrior horsemen, and walking down the red carpet to Africa’s premier film gala, flush with having learned the French for 35mm film (pelicule).

For more information, check out our guide to Burkina Faso:

Food and drink in Burkina Faso

Food

African dishes

The national staple is tô (sagbo in Moore), a white, starchy mountain made from pounded millet and water. Tasteless and filling, it’s often combined with a fairly tasty green sauce (sauce feuille) made of baobab leaves, rich in calcium.

A more adventurous alternative is foutou, from neighbouring Côte d’Ivoire. It has a similar texture to tô but is made from yams. Foutou banane has plantain added and is delicious.

Classic dishes are riz gras and riz sauce, available at resto-bars across the country. Riz gras is rice covered with cabbage and bits of bitter African aubergine, with a few morsels of meat in a tomato sauce. Riz sauce consists of plain white rice with one of two sauces – sauce tomate is the most common, but you’ll also find sauce arachide, a thick reddish-brown groundnut sauce; a Burkinabe satay. Vegetarians take note: both have chunks of meat thrown in. Prices vary (150–1,500f a plate), depending on how smart the restaurant, and how much sauce you get. Fish and chicken soup are readily available. Th ey can look unappetising, but generally slurp down well.

Chicken is easy to come by in the smallest of bars, often killed the moment it is ordered and taking some time to arrive as a result. Be warned that nothing is wasted by locals – head, neck, eyes and all – although a maquis may take squeamish foreign sensibilities into account. Several tasty preparations mask the often poor quality of meat, including lime juice, mustard and onions, garlic, tomato and green peppers.

Two chicken stews, poulet yassa, strong on onions and lemon and from Senegal, and poulet kedjenou, from Côte d’Ivoire, are popular in Burkina. Poulet bicyclette is a classic, local take on rôtisserie chicken and when done well, with lashings of garlic, is difficult to beat. Poulet rabilet makes good use of soumbala, in a pungent, slightly sweet, nutty sauce.

Another Burkinabe classic is pintade – domesticated guineafowl; their raucous cackling is commonly heard across the country. You’ll find them roasting alongside chicken at countless roadside chop stalls; they tend to cost a bit more. They also feature on numerous restaurant menus.

With so much cattle in the country, there is also plenty of beef on offer. Small chunks, skewered and grilled, are called brochettes, and available for as little as 100f, sometimes served with onions, tomatoes, green peppers and plenty of garlic. You can also find merguez sausage.

Pork is popular in animist/Christian districts. A favourite way to cook it is in a little mud-brick oven, when it’s known as porc au four (oven-cooked pork). Some maquis make it their speciality and are justly famous as a result; good porc au four is heavenly. It’s more of an option for late morning/lunchtime than for evenings. Not to miss out on a treat, Muslims have their own variation – oven-cooked mutton, or mouton au four.

Agouti is a gamey, rich meat that could easily pass for rabbit when you don’t know what it is. When you learn that it is cane rat by another name it quickly becomes a little harder to swallow. Dogs and cats are also eaten in Burkinabe villages.

If you see anyone with food in front of them, wish them bon appétit. This is often met with the response vous êtes invité (you are invited) – not an actual request to share the meal so much as a warm expression of hospitality.

In the markets

A wander around any town market will offer several eye-openers, along with a good selection of tomatoes, onions, peppers, aubergines and garlic. Soumbala smells, and tastes, of dirty socks. It is a bundle of tightly packed soft black balls made from fermented nere seed, high in protein. It’s pretty much the original African stock cube, and is used to add fl avour to dishes, although it’s something of an acquired taste. Children are also particularly fond of the sweet yellow powder found inside nere pods. Kurakura is the equivalent of the Burkinabe pretzel, made of dried peanut butter.

Dried fish, flat and angry-looking, can be underestimated. One poor traveller once combined the dried offering from the marketplace with lettuce and cucumber in a sandwich. Suffice to say he didn’t get much beyond a bite. His error was to eat it raw; it is another pungent seasoner used as a stock cube, dispersed in giant pots of liquid with stewed vegetables and sometimes meat, to accompany starchy tô, or rice for special occasions. You may even see women selling pieces of calcium-rich cement, which expectant mothers are advised to chomp on for the sake of junior.

Street food

Watching the preparations for Burkina’s endless night-time meat barbecues can be fascinating, if a little off -putting. Men bring razor-sharp machetes down onto a wooden chopping block, splicing all manner of meat cuts into small chunks. You can’t help but shut your eyes in an involuntary wince every time the knife comes down. Portions are parcelled out in brown paper over grills, and a powerful orange spice, called can-can-can and made from groundnuts and chillis, is added. It makes anything taste edible, and has a local reputation for aphrodisiac properties.

Day and night, women fry up plantain and maize on the streets, sell mangoes and groundnuts and fry up starchy snacks. Samsa (beignets in French) is made from black-eyed beans (benga), pounded until their starchy skin comes off. The remaining powder is added to water, fashioned into rounds and fried in shea butter. Eaten hot, ensuring flies have no time to settle, they’re pretty good. You can also pick up sesame-seed biscuits – shaped like hearts come Valentine’s Day – in every street-side shop and petrol station.

Drinks

Soft drinks

With so much fruit in Burkina, delicious juices are available, often sold on the street in 50f plastic sachets. Bissap juice is a bit like a cross between elderberry, cranberry and blackberry, made from deep purple petals of the bissap flower. Tamarind juice looks like light-coloured Coca-Cola, but tastes entirely different: sweet, rich and slightly spicy. Limburghi, or gingembre (ginger juice), can really pack a punch and, served ice-cold, is delicious. Brakina, the nation’s brewer, also makes a range of soft drinks. Flavours such as mango, cola, pineapple and fruit cocktail can become a bit sickly after a while, but their main advantage is that they come in plastic bottles, so you can take them on the road with you. They can be bought from street-side kiosks from 300f. The canned, non-alcoholic version of Guinness, called Malta, is also available.

Sharing Chinese tea, oft en several servings from the same pot, is a much-enjoyed social activity. The preparation process has a laborious, ritualistic element to it that, rigorously observed, can take half an hour, providing the opportunity for a good gossip. A small iron stand is swirled around to introduce as much air as possible to the coals, and a small teapot placed on top to cook slowly. When finally ready, the dark tea is poured into small thimble-like glasses, with a fine froth on the top. This ensures the tea is not too hot when it touches the lips. The more froth you’re offered, the greater the honour.

Beer

Burkina’s two main beers are Brakina and So.b.bra (pronounced ‘So-baybra’), sold in big 650ml bottles (about 600–800f). Both have a delicious wheaty taste and the latter is slightly stronger. The slightly more upmarket favourite is Flag, brewed in Burkina but hailing from Senegal. It is available in a smaller 330ml bottle (known as a flagette) and is slightly heavier. Castel is another option. Locally brewed beer (dolo or chapalo) is widely available in villages and towns. Palm wine (banji) is popular in the south, as is an extremely strong sugarcane liquor known as qui m’a poussé (‘who’s pushed me?’).

Health and safety in Burkina Faso

Health

People new to exotic travel often worry about tropical diseases, but it is accidents that are the biggest danger. Road accidents are very common in many parts of Burkina Faso so be aware and do what you can to reduce risks: try to travel during daylight hours, always wear a seatbelt and refuse to be driven by anyone who has been drinking. Listen to local advice about areas where violent crime is rife too.

Before you go

Preparations to ensure a healthy trip to Burkina Faso require checks on your immunisation status: it is wise to be up to date on tetanus, polio and diphtheria (now given as an all-in-one vaccine, Revaxis, that lasts for ten years), and hepatitis A. Immunisations against cholera, meningococcus and rabies may also be recommended. Proof of vaccination against yellow fever is needed for entry into Burkina Faso if you are coming from another yellow fever endemic area. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that this vaccine should be taken for Burkina Faso by those over nine months of age, although proof of entry is only officially required for those over one year of age.

If the vaccine is not suitable for you then obtain an exemption certificate from your GP or a travel clinic. This does mean that you will not be protected against the disease, which puts you at risk. Yellow fever is transmitted by day-biting mosquitoes, so if the trip is imperative then wear loose long-sleeved clothing and protect exposed skins with insect repellents.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on http://www.istm.org/. For other journey preparation information, consult www.travelhealthpro.org.uk (UK) or http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ (US). Information about various medications may be found on www.netdoctor.co.uk/travel. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Road safety

With their overlapping traffic of bicycles, mopeds, cars and enormous trucks, Ouaga’s roads can be a terrifying experience. Throw in the odd donkey cart, crazed coach drivers and wheeled trolleys carrying such hazards as long steel rods, it is a wonder the instance of accidents in Burkina Faso is not higher.

When driving in the two main cities, constant vigilance is absolutely vital. Cars drive on the right. At roundabouts, traffic coming onto the roundabout has right of way, so vehicles on the roundabout must stop to let oncoming traffic pass.

Crime

It is difficult to think of a safer country than Burkina Faso. Certainly, downtown New York, London or Sydney pose more problems for strangers late at night than Ouagadougou, which at no stage felt threatening. Burkina Faso has the lowest murder rate in the world, although whether that’s down to under-reporting is hard to say. Despite gun shops adorning what can sometimes feel like every urban street corner, armed violence is rare.

Female travellers

Women travelling in the company of men are unlikely to find much bother, other than being asked how their husband is doing and, if they’ve not got either a husband or children, why not and hadn’t they’d better hurry up and get on with it. For women travelling alone, it is a different matter. Claiming you have a boyfriend, girlfriend or husband is unlikely to cut much mustard. ‘Yes, I have a girlfriend too, now let’s go and get it on’ is as likely as not to be the reply.

Most women say they don’t feel in danger, but are worn down by persistent and unpleasant advances. There is the occasional stereotyped view that travellers and tourists are easy, and some men are quick to try their luck. It pays to be aware and exercise caution. Be on your guard at rowdy nightclubs, meeting places for touts on the streets, and bus and coach stations. If you feel uncomfortable in a taxi, ask to be let out before you reach your ultimate destination, or choose a suitably important person’s home as your destination – the local chief ’s or naba’s palace, for example.

Don’t expose unnecessary flesh. While girls in gold shiny singlets whooshing round on bikes are de rigueur for Ouaga, it’s best to reassess outside the capital. In Burkina, legs are considered sexually attractive. Short skirts and shorts court controversy. On the other hand, wearing a piece of colourful local cotton, no matter how badly or self-consciously, acts as an ice-breaker. Women will notice the effort, love the idea and even give tips on how to tie it properly.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Homosexuality is legal in Burkina Faso; the legal age of consent for same-sex activity is 21 (it’s 13 for heterosexuals). However, bear in mind that society is very conservative and that homosexuality goes against most people’s religious and traditional beliefs; so it’s best to be discreet.

Travel and visas in Burkina Faso

Visas

If you are not a citizen of ECOWAS (the Economic Community of West African States), you will need a visa. In 2010, there was a massive price hike, especially for visas on arrival; so if you fail to get one in advance, you will have to pay a whopping 94,000f at the airport (it would appear that the same applies at borders), which is roughly double what you would pay back home. This can then be converted to a three-month single-entry visa at the Service des Passeports in Gounghin, a process that takes at least two days . Should you wish to stay for longer, or need multiple entry, there will be further expensive charges. So, the message is clear: get one before coming. They’re still not cheap as African visas go, but you will save time as well as money. All visas require two passport photos.

Getting there and away

By air

Getting to Burkina is likely to be the single biggest cost. Most connections go through Paris, and Air France has the best and most frequent service. Cheaper options include Point Afrique, Royal Air Maroc and Afriqiyah Airways.

Overland

Crossing into Burkina from neighbouring countries now seems to be subject to the same massive 94,000f fee as at the airport. If you have a visa already, you should have no problem.

If you are coming from Mali, the main tourist crossing point is close to Dogon country, between Koro in Mali, and Thiou in Burkina. The main entry point from Niger is between Makalondi and Kantchari; from Benin it is between Dassari and Tindangou; from Togo between Senkanse and Bitou; and from Ghana at Paga.

Getting around

There are an increasing number of good tarmac roads in Burkina; once the Koudougou–Dedougou stretch is finished (scheduled for 2013), all the main arteries heading out from Ouaga and Bobo will be covered. The quality of unpaved roads varies enormously, depending on volume of traffic and time of year.

There is a good network of coach companies, many of which run decent services and leave on time. Moped is the favoured vehicle for locals in town and for short spurts between towns as well, and it is easy to hire them wherever you fi nd yourself. For some destinations, car or 4×4 will be the only option, however, and even then some smaller roads will be ropey if not impassable, especially in the rainy season. Only train enthusiasts should try the rail network.

If none of the above applies, there will always be a bush taxi, or local vehicle passing between towns on market days or delivering the post.

By bus

Burkina is brimming with coach companies, and Ouaga is the central departure point. Th ere is competition on all routes, with daily departures; and although companies tend to co-operate on setting prices, fares have dropped a little over the last fi ve years. Budget on about 1,500f for every 100km. Nearly all allerretour (return) tickets are cheaper than the price of two singles. Timetables are generally adhered to, and it pays to arrive at least half an hour before the allotted departure time.

Local opinion tends to vary about which lines are flavour of the month. Companies operate their very worst vehicles on specifi c routes, though with more tar roads being completed and coaches abandoning those that aren’t, this is less of an issue these days. Th ere are five companies – TCV, STAF, Rakieta, TSR and STMB – that will meet most travellers’ needs; they all pride themselves on reliability and punctuality, and generally achieve both. Overall, STAF has a reputation for fast drivers and loud music, while STMB’s buses, once the best, are now the most run-down.

There will be a supplement for extra luggage, such as a bicycle (250f) or moped (500–1,000f) on the roof.

In addition to main depots, buses have secondary garages, so it’s worth checking the departure point in advance. Tickets are usually valid for one month, so buy them in advance on busy routes if you want to be sure of getting a seat. If you’re a little perplexed by the range of companies on offer, work out where you want to get to and stop someone to ask which company you need and where to go. There is always an answer.

By bush taxi

Bush taxis are a great option when coaches don’t dare service a particular destination, or for local hops from market day to market day.

It’s easiest to pick up a bush taxi at a town’s local gare routière, where you will spot Toyota minibuses and Peugeot 504s. If not, try the poste de police at the end of town since all cars and trucks have to stop here. It’s wise to approach the police officers, shake hands and explain your presence. Then just sit and wait. Prices depend on distance and state of the road, usually about 1,500f for a 100km stretch on tarmac. Count on paying up to twice as much for dilapidated dusty roads. Hiring an entire bush taxi means you get to choose the destination (known as a déplacement), but you pay for all the seats.

By moped and motorbike

The motorbike (commonly called a moto, whatever its size) has replaced the horse as a Burkinabe’s pride and joy. They are everywhere, from put-put mobylettes that are part-bicycle, part-moped, to heavy-revving Yamaha beasts. They are vulnerable to road accidents, particularly in Ouaga.

Outside Ouaga, Bobo and Banfora, there are few official moped-hire outlets.

Ask at your hotel, however, and invariably a battered machine will turn up within minutes, exhaust on the verge of falling off, petrol tank relying on fumes only. You may have to bargain, since owners are occasionally loath to lend their only means of transport to strangers. Expect to pay 2,500–5,000f per day (excluding petrol) for a P50, the dinky little 50cc models that are easy to use and most commonly seen around town, and more for bikes with gears and clutches.

By car

It will certainly make life easier to have a 4×4, but it’s not your only ticket for getting around. In the wet season, however, many roads become impassable, especially to the north and in the far southwest.

Car hire

If you’re hiring a car, check it well. Make sure you have all the proper paperwork – international driving licence, registration, MOT, insurance – or risk paying fines several times if you are stopped by police. Agree price and terms in advance, especially in case of damage, and sort out whether you will be reimbursed for any repairs you pay for on the road. If you want to drive outside Ouagadougou or Bobo, many companies will rent out a car only on condition that it comes with a chauffeur – which has both advantages and disadvantages. Cars tend to cost around 20,000–30,000f a day, 4x4s 40,000–70,000f. Prices often include chauffeur but exclude fuel.

By train

Despite the war in neighbouring Côte d’Ivoire, SITARAIL trains go regularly between Ouaga and Abidjan. Services leave Ouaga on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday at 07.30 for Abidjan, stopping at Koudougou (1,500f), Bobo (5,000f) and Banfora (8,000f). The return journey from Abidjan should pass through on Wednesday, Friday and Sunday in the evening.

By air

For the wealthy or those in a hurry, Air Burkina (Tel: 50 49 23 45/46/47) has internal flights to Bobo. You can also hire a small Cessna and pilot for trips from Ouagadougou to tiny airfields in far-flung corners of Burkina and beyond. Richard, at Hotel Ricardo (Tel: 50 30 70 72), is your man, with prices from 160,000f an hour (petrol price permitting).

By bicycle

This is the preferred method of transport for millions of Burkinabe. In Ouagadougou, bikes of all shapes and sizes throng the streets, sometimes five or six abreast at rush hour. You can always find someone prepared to hire out a bike for a day or two if you want cheap transport to explore dusty streets or surrounding countryside. The quality varies enormously, but don’t expect anything flash.

When to visit Burkina Faso

Received wisdom is that you can only visit Burkina between October and February, and most recommend November and December as the best months of all. While the weather is at its most palatable then, there is no need to restrict oneself to such a small window. Whatever the season, Burkina has something to offer.

Any chance to tie in a trip with one of Burkina’s numerous large-scale international festivals – the biennial pan-African cinema festival Fespaco, held every odd-numbered year in February, the arts and crafts extravaganza SIAO, held every even-numbered year in October, or Bobo-Dioulasso’s culture week, held in March every even-numbered year – is worth taking.

Climate

West Africa does not really have weather, in the sense of the daily changes experienced in temperate regions. It has climate instead, created by enormous air masses shifted by global forces across the region as a whole. Burkina sits across three climatic zones, which experience a decline in rainfall and shorter wet season as one moves from south to north. The Sudano-Guinean zone covers the southwestern bulge of the country that extends towards Côte d’Ivoire. This is the wettest part of the country, where the rainy season runs for a full six months from May to October, with maximum rainfall of up to 1,300mm a year.

The Sudano-Sahelian zone is the largest climatic region, covering half of Burkina’s surface area, and generally receives between 600 and 1,000mm of rain each year. Here the rains tend to finish slightly earlier, in September. The Sahelian zone, situated in the northernmost quarter of the country, is the driest region of all, seeing as little as 150mm of rain each year. Although the arid semi-desert of the Sahel currently covers 25% of the country, it is reckoned to be encroaching by 5–10cm each year, as overexploitation of the land and the destruction of plant cover, coupled with worrying trends in overall global warming, hasten the onset of desertification.

Generally speaking, landlocked Burkina escapes the debilitating humidity of its coastal neighbours, although daily temperatures tend to be slightly higher, averaging around 35°C. During the cooler periods, the temperature can drop sharply at night, down to as low as 5°C in the Sahel. In general, count on temperatures rarely falling below 30°C. In the dry season, the major metereological feature, apart from the unrelenting heat (which can hit 45°C), is the Harmattan wind, which blows from the northeast, bringing with it the sand of the Sahara. This peaks in February and early March, with the sun becoming completely obscured on some days.

Calendar

February: Cannes in Africa

Every odd-numbered year, the glitterati of Africa’s film industry come together in Ouagadougou to celebrate the best of the continent’s varied, vibrant cinema.

March: Bobo culture week

Every even-numbered year, Burkina Faso’s second city Bobo-Dioulasso hosts Semaine National de la Culture, a literary and arts festival that is the envy of the region.

April: Hot mask fests

As the dry season heat intensifies, local communities all over Burkina Faso come together to give thanks to the ancestors and spirits in fantastic masked celebrations that are unmissable.

October: Souvenir heaven

Every even-numbered year, the capital hosts a major festival that brings together some of the best examples of African jewellery, statuary and textiles. Do not miss the chance to take back some wonderful gifts.

Things to see and do in Burkina Faso

Bani

To some visitors, Bani is one of the most memorable villages in the country, with its stunning collection of hilltop mud mosques. Others feel the entire town is reaching out for the tourist ticket in the most crass of ways. While it’s true that on arrival you are likely to be somewhat swamped by children asking for cadeaux, the story behind the mosques that ring the town is fascinating.

Senoufou villages

Squeezed into the west of Burkina and overflowing into Côte d’Ivoire and Mali, the Senoufou are revered as a magical and mysterious people. They are held in such awe that some credulous Mossi are prepared to tell you that cannibalism is still practised among certain sects, if demanded by the chief or the spirits.

The Senoufou believe in a supreme being and creator of the universe, the god Koutyolo. In some versions of the myth he has fallen asleep, in others he was disgusted with his final creation, man – either way, he has withdrawn from the world, leaving it a guideless place. A kinder female god, Katielo, is a mother figure who exerts a more positive influence, overseeing the village and protecting the sacred wood. It is her influence that has enabled man to evolve and learn the arts of farming and music.

Bobo-Dioulasso

If you have the time for only a few days in the country, it may make sense to base your stay in Burkina’s second city, which is both a great hangout in its own right and within easy reach of a variety of trips. Burkina’s live-music capital is a joy for travellers, and much easier to get a feel for than the larger, busier neighbourhoods of Ouaga.

The lush landscape brings sweet relief from the arid climate of the central plateau and there are easy links to Mali and Ghana. Because of this, the town has more of an ostentatiously backpacker’s feel than other parts of the country and a great range of cheapish accommodation. Correspondingly, there is likely to be a profusion of guides offering their services.

Gobnangou Escarpment

The Gobnangou massif (Falaise de Gobnangou) extends from the Arly Reserve to Niger, looming over the plains of Gourmanche country in great fissured cliffs and descending slowly to a low rise further east. The cliffs shelter vulture colonies and are good for other raptors (including fox kestrel), swifts and swallows.

Villages nestle beneath it, comfortable in the protection it provides; waterfalls tumble down it, caves lie hidden in its depths and climbers can find an increasing number of routes to inch their way up it, thanks to the efforts of La Federation de l’Escalade Italienne (FASI). They have already opened several climbs and are aiming to create about 100.

Pama

Once capital of the region, Pama now languishes under a gentle haze of quiet and reverence. A selection of elegant resthouses nearby makes for a tranquil retreat, and it’s also a great staging post for trips into Benin’s Pendjari National Park. Visas can be bought on the border for 10,000f, and travel agencies in Ouagadougou, as well as hotels in the region, can organise the trip.

Domes de Fabedougou

In Western Australia, the bulbous rock formations of the Bungle Bungles draw thousands of tourists every year. Burkina has an almost geologically identical feature, yet it is almost entirely unheard of. So the magnificent, hauntingly beautiful Domes de Fabedougou rest undisturbed, all the better for their desolation, bar local cows and herders. Better still, they are there for the climbing, and there are some easy ascents up the cracked sides of the domes, which sit side by side like a series of enormous grey igloos.

Nazinga Game Ranch

With 800 elephants in this smallish park, an encounter is basically assured. During the height of the dry season, when water elsewhere is hard to come by, you simply need to turn up at the lakeside camp at around noon for a spectacular bathing show.

The observation area on the lake’s edge puts you right at the heart of the action. Young bulls, absorbed in the minutiae of their daily routine, stop and slowly look up, within touching distance. You can see the crevices and cracks of the caked mud on heffalump sides, the layer of stubbly hair covering trunks, and feel their elephantine breath on you. Elephants regularly wander through the camp to chow down on the well-watered shoots and leaves. If staying the night, take a torch if you’re prowling the campsite, to avoid bumping into one of the hairy monsters.

Sahel

Mention the north to anyone who knows Burkina well and a misty look may come into their eyes. ‘Ah,’ they’ll whisper, barely audible in their reverence: ‘I love the north.’ Even the fierce desert heat can’t drive them away. Travellers lose themselves to the Sahel. They traverse the dunes, sleep beneath its enormous canopy of stars, and a part of them never comes back. Couples love the romance so much they marry there.

Ouagadougou

It’s not just the spectacular name that makes Burkina’s capital so enticing. There might not be much in the way of sightseeing or architectural marvels, but as faras people-watching, eating and dancing goes, its dust-choked streets and endlessselection of gardens and outdoor bars off er a brilliant bazaar of modern west African life – all in a city small enough to get across in about half an hour, and so safe it puts Western capitals to shame. Ouaga also bills itself as a global arts capital, on a par with New York, London and Paris, and the wealth of culture on offer is not to be missed. There are festivals throughout the year – dance, theatre, poetry, film, modern art, jazz, masks, hiphop, puppetry – and cutting-edge craft smanship on offer.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Burkina Faso: