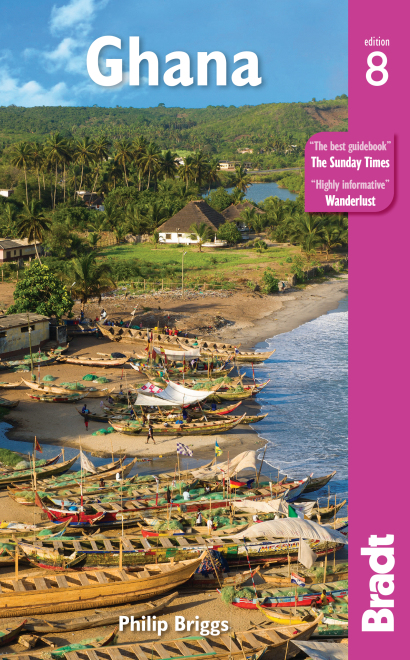

Tangibly steeped in history and tradition, yet paradoxically also building towards a brighter future, Ghana is simply one of Africa’s most rewarding and exciting travel destinations.

Philip Briggs, author of Ghana: the Bradt Guide

Ghana is a travel destination of immense natural and cultural diversity. It stretches inland from a sultry Atlantic coastline on the Gulf of Guinea through to the dry Sahelian plains bordering Burkina Faso. Only six hours’ flight from most European capitals, this famously hospitable West African nation is both an ideal holiday venue for first-time visitors to Africa and a rewarding destination for more seasoned travellers. Delightfully down-to-earth and free of tourist-circuit trappings, Ghana also has the advantage, at least for Anglophone travellers, of being one of the few West African countries where English is widely spoken.

Architectural attractions include the string of European forts and castles that line the former Gold Coast, some more than 500 years old, as well as the fantastic adobe mosques of the north, and the ancient fetish shrines that dot the countryside around Kumasi, capital of the venerable Ashanti Kingdom. For outdoor enthusiasts, the vast Mole National Park offers the opportunity to track elephants on foot, while the dense rainforests inland of the coast are home to a wealth of rare birds and monkeys. Hikers are drawn to the waterfalls and scenic slopes of the easterly Volta Region, while beach lovers can choose between the bustling surf scene at Busua or more isolated resorts in the vicinity of Cape Three Points and Beyin.

For more information, check out our guide to Ghana:

Food and drink in Ghana

Food

Local dishes generally comprise a starchy staple and some sort of soup or stew, often liberally flavoured with a hot, red powdered-pepper seasoning. Among the great many staples you’re likely to encounter, the most popular are fufu, kenkey, banku, akple, tuo zafi (TZ), omo tuo (rice balls), boiled rice, and fried yam or plantain. Particularly popular in the south, fufu is made of cassava, plantain or yam, mashed until the starch breaks down and it becomes a gooey ball, then cooked with no water to form an even gooier one. It is served submerged in a soup, typically palm nut, groundnut (peanut), or a chicken-and-tomato-based ‘light soup’, and is not supposed to be chewed, but rather mashed against the palate with your tongue and swallowed that way, as otherwise you could chew on it for ages!

Similar to each other in taste and sticky texture are banku and akple, both made of fermented maize and cassava, and often eaten with okro stew for double helpings of that gelatinous feel! Akple is particular to the Volta Region, while banku is found throughout Ghana. Kenkey is especially common among the Fante and Ga (indeed, they make two separate varieties of it) and also made of fermented maize, but is much firmer than banku or akple, as it’s boiled in a removable wrapping of plantain leaves or corn husks before being served with a spicy tomato sauce or similar. Largely restricted to the north, tuo zafi is a millet- or maize-based porridge. Fried yam, often sold at markets, is not dissimilar in taste and texture to potato chips – though, when bought on the street, it often has a lingering, petroleum-like taste, presumably a result of using the same oil for too long – and is great eaten with spicy tomato relish, or soft green palava sauce made from spinach-like cocoyam leaves.

Drink

Most visitors to Ghana drink a lot more than they would at home, thanks to the hot sticky climate, and since tap water is not recommended, you will probably find yourself going through several bought litres of water daily. This can be purchased in several forms. Conservative travellers will probably prefer to stick with 1.5-litre bottled mineral water, which is known locally as Voltic (after a well-known brand), and is widely available, inexpensive by international standards, and can usually be bought chilled on request. A far cheaper option, which most travellers drink without any problem, are the factory-sealed 500ml sachets known as ‘pure water’. These labelled sachets contain genuine purified water (often with a strong chemical taste to prove it), are usually chilled, and cost the equivalent of US$0.05 (or if you are based somewhere for a while, you can buy a pack of 30, containing a total of 15 litres, for US$1).

Elsewhere, mainly in small villages, ‘ice water’ is sold in unmarked plastic bags and comes from an undetermined source, so is perhaps best avoided. For a change of flavour, you can spice up the water with a sachet of Tang, a powdered orange or mango drink with added vitamins. Bottled pure orange and pineapple juice from Accra is also widely available at bars and restaurants catering to tourists. Also worth trying are the surprisingly good, sweetened Kalyppo fruit juices that come in 250ml packs. A cheap, refreshing and highly nutritious drink is fresh coconut juice. You’ll often see street vendors selling piles of coconuts, particularly along the coast – just ask them to chop one open and you can slurp down the liquid.

Health and safety in Ghana

Health

With the right vaccinations and a sensible attitude to malaria prevention, the chances of serious mishapin Ghana are small. It may help to put things into perspective to point out that, after malaria, your greatest concern in Ghana should not be the combined exotica of venomous snakes, stampeding elephants, gun-happy soldiers or the Ebola virus, but something altogether more mundane: a road accident.

Road accidents are very common in many parts of Ghana so be aware and do what you can to reduce risks: try to travel during daylight hours, always wear a seatbelt, and refuse to be driven by anyone who has been drinking. Listen to local advice about areas where violent crime is rife, too.

There are private clinics, hospitals and pharmacies in most large towns, and doctors generally speak fluent English. Consultation fees and laboratory tests are remarkably inexpensive when compared with most Western countries, so if you do fall sick it would be absurd to let financial considerations dissuade you from seeking medical help. Commonly required medicines, such as broad-spectrum antibiotics and Flagyl (though tinidazole is easier to take, it is not generally available in Ghana), are widely available and cheap throughout the region, as are malaria cures and prophylactics. It is advisable to carry all malaria-related tablets (whether for prophylaxis or treatment) with you, and only rely on their availability locally if you need to restock your supplies.

Safety

Ghana is overall a very safe travel destination, certainly where crime and associated issues are concerned. Levels of hassle are low, too, and tolerance for the quirks of outsiders is high, though it should be pointed out that, as is the case almost anywhere in the world, breaking the law – in particular the usage of illegal drugs – could land you in big trouble.

Dangerous driving is probably the biggest threat to life and limb in most parts of Africa. On a self-drive visit, drive defensively, being especially wary of stray livestock, gaping pot-holes, and imbecilic or bullying overtaking manoeuvres. Many vehicles lack headlights and most local drivers are reluctant headlight-users, so avoid driving at night and pull over in heavy storms. On a chauffeured tour, don’t be afraid to tell the driver to slow or calm down if you think he is too fast or reckless. Taxi drivers in Accra have also been known to attempt scams on travellers.

Female travellers

Women travelling alone have little to fear on a gender-specific level, and will often find themselves the subject of great kindness from strangers who want to see that they are safe. The most hassle you are likely to face is heightened levels of flirtatiousness from many Ghanaian men, with the odd direct proposition and a million marriage proposals thrown in. They can be persistent, but barring the marriage part, it’s nothing that you wouldn’t expect in any Western country, or – probably with a far greater degree of persistence – from many male travellers. It may sometimes help to pretend you have a husband at home or waiting for you in the next town – in which case, a wedding ring is accepted as ‘proof’ – but be aware whilst you are fabricating that he is almost worthless without having given you some ‘issue’, or children. Being married without offspring attracts the twin reactions of vigorous proposals from ‘better’ men, and sorrowful looks based on the assumption that your husband is impotent. If anyone does overstep the mark – by touching you, for instance – do make a fuss and slap the offending hand away to underscore that it is not acceptable.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Any act of male homosexuality (defined as being ‘deemed complete upon proof of the least degree of penetration’) is criminal in Ghana. Offenders risk a prison term of up to three years if the act is found to be consensual, and between five and 25 years if it isn’t. The law is ambiguous when it comes to sexual activity between females. Legalities aside, the vast majority of Ghanaians would regard any homosexual act or relationship, whether between male or female, or local or foreigner, to be profoundly unnatural and sinful. Over the past ten years or so, ugly anti-gay rhetoric spouted by religious leaders, much of which links homosexuality to satanic influences and a broader Western decadence, has been reported prominently by the sensationalist local press, affording the issue a far higher profile than was the case ten years ago.

Travelling with a disability

Many of Ghana’s highlights – such as the coastal forts and the Kakum rainforest canopy walkway – are going to present a challenge to people with mobility problems, but don’t let this exclude the country from your travel wish list. Depending on your ability and sense of adventure, most obstacles are surmountable and the rewards are well worth the effort. Ghanaians are well known for their friendliness and hospitality, so if you need help, you will receive it!

Travel and visas in Ghana

Visas

Check well in advance that your passport hasn’t expired and will not do so for a while, since you may be refused entry on a passport that’s due to expire within six months of your intended departure date. Visitors of practically all nationalities require a visa, which must be applied for in advance at the Ghanaian diplomatic mission (embassy or high commission) in your country of residence, where one exists. This is often a complicated and costly process, not least because many such missions are notoriously unhelpful and unresponsive (the Ghanaian embassy in the USA has a particularly bad reputation for mislaying passports, not answering phone calls, etc), so it is advisable to set things in motion as far in advance as possible. People travelling overland to Ghana should be aware that it is no longer possible to get a Ghanaian visa in neighbouring countries unless you are a resident of that country (for instance, the embassy in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, will only process visas for residents of Burkina Faso).

Should you want to stay in Ghana for longer than 60 days, you will have to apply for a visa extension once you are in the country and to pay an additional fee for every extra 30 days, regardless of whether you have paid for a single- or multiple-entry visa. It’s worth knowing that a visa extension in Accra might take two weeks to process, whereas it shouldn’t take more than 48 hours at any other regional capital – although a considerably more attractive option might be to buy a multiple-entry visa and then to cross into one of the neighbouring countries and get an extra 60 days on your return.

Getting there and away

By air

Airlines with scheduled flights to Accra include British Airways, Brussels Airlines, Delta Airlines, Egypt Air, Emirates, Ethiopia Airways, Iberia, KLM, Kenya Airways, Lufthansa, Royal Air Maroc, RwandAir, South African Airways, TAP Portugal and Turkish Airlines.

Flights from the USA and Canada tend to be expensive, so North Americans with more time than money may find it cheaper to fly to London, or elsewhere in Europe, and organise a ticket to Africa from there. As with most destinations, round-trip tickets to Ghana are typically a much better deal, so we recommend going this way if possible, rather than buying a one-way ticket and organising your return once you are there. Additionally, you may hit serious problems with airport immigration officials if you can’t show them a return ticket on arrival.

Overland from Europe

There are two overland routes between Europe and Ghana. Both start in Morocco and involve crossing the Sahara, one via Algeria and the other via Mauritania, then continuing through Mali and Burkina Faso. The Algeria option has been impassable for some years now, and these days Mali is also impossible to enter from the north, making the Mauritania route the only viable Sahara crossing in West Africa at the time of writing. Still, the situation with either route is highly changeable and you should seek current advice. For UK-based readers, the best way to gauge the situation is to contact the many overland truck companies that advertise in magazines such as TNT and Time Out. Unless you have a reliable 4×4, joining an overland truck trip is almost certainly the best way of doing this difficult route, especially if you have thoughts of continuing through the Democratic Republic of Congo to East Africa.

Getting around

Car rental and driving

Formal car rental options in Ghana are more or less restricted to Avis, Europcar and a number of private tour operators in Accra. In most cases, they will only rent a car with a local driver, whose expenses should be covered in the asking rate. An affordable alternative to renting a vehicle formally is to charter a taxi driver for one or more days – which, if you choose the right driver, means you also have a guide, interpreter and evening companion for the bar. The rate for this sort of service is highly negotiable, and it will depend on the distance you want to travel, the number of days, and whether fuel and the driver’s meals and room are included, but at worst you should be looking at around US$30 daily, exclusive of extras such as fuel – and a lot less in rural areas or the north of the country. If you want to rent a taxi as a private charter on a one-off basis, bank on a fee of around US$7–10 per hour inclusive of fuel and unlimited kilometres.

By public transport

Major roads through Ghana are covered by a variety of public transport, divisible into five broad categories, in descending order of comfort: air-conditioned coaches, air-conditioned vans (known variously as Fords, Stanbics or Yutons), Metro Mass buses, trotros (also sometimes called lorries) and shared taxis. In small towns and villages, all public transport generally arrives at and departs from one central terminus (usually referred to as the ‘station’, or ‘lorry station’). Most larger towns have several different stations, sometimes serving different types of transport or individual operators, other times a set of destinations in one direction. Most road transport doesn’t operate to a fixed schedule. Instead, vehicles simply wait at their designated station, and leave as soon as they are full. Occasionally while halfway through a trip, the driver will pull over, all passengers will disembark, then clamber aboard the next bus coming by, for reasons unclear for those not versed in the local language. This can all seem rather chaotic to first-time Africa visitors used to more formal train and bus timetables, especially where departure points are decentralised, but once you adapt, you’ll find that getting around Ghana’s roads is very cheap and straightforward, though the standard of driving leaves a great deal to be desired on the safety front.

When to visit Ghana

Calendar

April: paraglide from the Kwahu Plateau

Since 2003, the Ghana Paragliding Festival is an enjoyable annual fundraising event held at Nkawkaw, at the base of the Kwahu Plateau. In addition to paragliding from the tall cliffs above Nkawkaw, this festival – which takes place over the Easter weekend, usually in April – involves various traditional ceremonies and live music.

May: watch the famous Aboakyir Festival in Winneba

Said to be more than 300 years old, this popular festival in the first weekend of May is centred on a hunt in which Winneba’s oldest two Asafo companies, dressed in traditional regalia, attempt to capture a bushbuck using only their bare hands. The hunt takes place on Saturday and the captured animal is sacrificed to the oracles at a fetish shrine the next morning.

July: celebrate one of the country’s oldest festivals in Elmina

Thought to pre-date the arrival of the Portuguese at Elmina more than 500 years ago, the Bakatue Festival, held on the first Tuesday of July, heralds the start of a new fishing season. A variety of processions and competitions take place in the vicinity of St George’s Castle, the oldest European building in sub-Saharan Africa.

August: celebrate the Bontungu Festival in Anomabu

Set in the small but historic seaside town of Anomabu east of Cape Coast, the five-day Bontungu Festival is a riot of drumming and dancing rituals, held to invoke divine blessings for the coming year.

What to see and do in Ghana

Accra

It is tempting to introduce Accra as Ghana’s historical capital, or something similarly portentous. This, after all, is a city whose oldest Ga inhabitants settled there 500 years ago, whose coastline is guarded by a trio of 17th-century European-built forts, and which became a colonial capital back in 1877, when many other African metropolises – for instance Nairobi, Johannesburg and Addis Ababa – were still tracts of empty bush. Knowing this, Accra is perhaps something of a disappointment. Historic landmarks are sparse on the ground, and for the most part either closed to the public or surprisingly underwhelming – one notable exception is the colonial-era Jamestown Lighthouse, which offers an informal welcome to the curious visitor, and a superb gull’s-eye view over the old town.

In feel, Accra is a modern city. Emphatically so. Since the dawn of the colonial era, its population has grown from a few thousand to several million, so that it now ranks 11th on the list of Africa’s largest metropolitan areas. And while bespoke tourist attractions are few and far between, the old Ga quarters of Jamestown and Usshertown do possess a certain faded charm, while the more vibrant and modern districts of Adabraka and Osu are serviced by an alluringly cosmopolitan selection of bars, restaurants and other social venues.

Not the least of Accra’s assets is its amiability. Hectic it may be, chaotic in places, but few ‘developing world’ cities of comparable size feel as comparably safe and relaxed. As such, the Ghanaian capital tends to reward casual exploration. Scruffy lanes lined with open sewers and colonial-era homesteads might lead to grandiose independence monuments, to dazzling modern skyscrapers, to unkempt open spaces, or to rundown concrete blocks harking from the headiest days of Soviet town planning.

Boabeng-Fiema Monkey Sanctuary

This small but rather wonderful 2km² sanctuary was created in 1974 to protect the monkey population supported within a small patch of semi-deciduous forest centred on the villages of Boabeng and Fiema, which lie 1km apart in Nkoranza District. Two monkey species occur in significant numbers: Lowe’s mona and black-and-white colobus. The mona population is thought to stand at around 400 individuals, living in troops of 15–50 animals, several of which now have a territory in the forest fringe and adjacent woodland. The black-and-white colobus, with a population of 200 animals divided into 13 troops, are rarely seen outside the true forest. Recent reports of green, patas, spot-nosed and Diana monkeys remain unsubstantiated, but the forest does support a good variety of birds and butterflies.

Guided walks can be arranged at the visitor centre located beside the resthouse at the forest entrance. The village is the best place to see monkeys at close range. The unruly monas that scavenge here are particularly tame and spend a great deal of time on the ground; it is highly rewarding to be able to watch these normally shy forest monkeys interact at such close quarters. The colobus monkeys are more timid and tend to stick to the trees, but you should easily get a clear view of them, and it’s wonderful to see them leap between the trees with their feathery white tails in tow. A longer guided walk along some of the 10km of footpaths that emanate from the village provides an opportunity to see some of the many birds and butterflies, as well as a giant mahogany tree thought to be more than 150 years old. Small plastic bottles of the excellent local honey are on sale at the entrance, where there is also a good crafts shop.

Busua

Strung along a wide sandy beach for about 1km, Busua has long rivalled Kokrobite as the ultimate Ghanaian beach chill-out venue, though its relative distance from Accra and less densely clustered facilities mean that it generally comes across as quieter and less overtly touristy than its eastern counterpart. Flanked on the west by the Busua Lagoon, the beach is generally regarded to offer some of the safest swimming in the country, though (as with anywhere along the Ghanaian coastline) tides and currents can be unpredictable, so take local advice before you swim, and don’t venture out deeper than the locals do. Having attracted a steady influx of budget travellers to its beach since the 1960s, Busua has also emerged as a focal point of Ghana’s evergrowing surfing scene. While facilities are generally geared towards low-spending volunteers and backpackers, Busua does also cater to a more upmarket crowd, with the Busua Beach Resort in particular being a popular weekend retreat for expats associated with the mining industries in Tarkwa and Takoradi.

Since 2011, Busua has also been home to the Asa Baako Festival, which runs for three days every March and takes over the village with a series of concerts, parties, art exhibitions, sporting events, trekking, tree planting and more.

Cape Coast and Elmina

Owing to their great antiquity and nefarious role in the Atlantic slave trade, the castles at Cape Coast and Elmina are of global significance as the centrepieces of a UNESCO World Heritage Site embracing all the fortified buildings along the Ghanaian coast. Yet the towns over which they stand sentinel, far from being stuffy period pieces, are lively modern ports, steeped in Fante tradition and history, but also reflecting the contradictions and intricacies of 21st-century urban Africa.

Cape Coast

The attractive fishing port of Cape Coast, set on the east bank of the Fosu Lagoon, is steeped in history. Settled at various points by Portuguese, Danish, Swedish and Dutch traders, it became the coastal headquarters of Britain’s Royal African Company in 1664, and later served as the first capital of the Gold Coast Colony. The town’s antiquity is reflected in a varied range of architectural relicts spanning four centuries, most notably the hulking seafront presence of Cape Coast Castle, but also in its organic shape of tangled roads hugging the curves of low hills.

Elmina

Straddling the thin strip of land that separates the brackish Benya Lagoon from the crashing waves of the Atlantic, the strikingly attractive town of Elmina is the equal of nearby Cape Coast in terms of historical sightseeing, though it is often overlooked by tourists in favour of its larger neighbour. It started life as a fishing and salt-producing village at least 700 years ago and – despite having once formed the epicentre of the West African gold trade, first as the Portuguese and later the Dutch coastal headquarters – an overgrown fishing village is basically what Elmina remains today.

Eastern Highlands

The east of Ghana, though less geared towards upmarket tourism than the west coast, is a haven for independent travellers, rich in natural beauty and offering a wealth of low-key, low-cost travel possibilities to those with the initiative to take them up. For keen hikers and ramblers, the lush and relatively cool highlands around Ho and Hohoe are studded with the country’s highest peaks, as well as a plethora of accessible waterfalls and an excellent little monkey sanctuary at the village of Tafi Atome. The east coast, too, is rich in isolated, out-of-the-way gems, most notably the small ports of Ada and Keta, while the area immediately inland of Accra is notable, among other things, for the tranquil Aburi Botanical Garden and impressive Akosombo Dam on the Volta River.

Kakum National Park

Extending over an area of 375km² inland of Cape Coast, Kakum National Park protects the core of Ghana’s largest remaining tract of rainforest, parts of which also lie within the contiguous Assin Attandanso Game Production Area and Pra Suhien Forest Reserve. In addition to harbouring an immense diversity of plants and animals, Kakum is an important watershed, named after one of several rivers that rise within its boundaries and collectively provide water to 130 towns and villages, including Cape Coast. One of the most popular and accessible wildlife destinations in Ghana, the national park is less than an hour’s drive north of Cape Coast, whether you travel in a private vehicle or trotro. The main attraction for most visitors is a much-publicised canopy walkway that rises up to 40m above the forest floor, but birding walks and a limited range of other activities are also offered, albeit sometimes rather reluctantly.

Originally set aside as a forest reserve in 1931, Kakum was gazetted as a national park in 1992, partly at the initiative of local communities. The predominant vegetation type is moist semi-deciduous close-canopy rainforest, which is characterised by high rainfall figures (peaking between May and December) and an average humidity level of 90%. Parts of the park are ecologically compromised as a result of the extensive logging that took place in the 1970s and 1980s, but most of the forest remains in pristine condition, and logging has been outlawed within its boundaries since the national park was proclaimed.

Kumasi

The modern capital of Ashanti Region, Kumasi has also served as the royal capital of the Ashanti Kingdom for longer than three centuries. Yet, contrary to the sort of expectations conjured up by the epithet ‘ancient Ashanti capital’, one’s first impression upon arriving in Kumasi, particularly if you disembark near Kejetia Circle, is less likely to be rustic traditionalism than daunting developing-world urbanity. This is the largest settlement in the Ghanaian interior, with a population of approximately 2.2 million according to 2018 estimates, and one of the most hectic cities we’ve encountered anywhere in Africa.

Surging throngs of humanity and constant traffic jams emanate in every direction from the market and lorry station, creating an emphatically modern mood that can be positively overwhelming to newcomers, particularly those arriving from the relatively provincial north. For all that, Ghana’s second city ranks as a ‘must-see’ in most people’s book. True, historical Kumasi amounts to little more than the late 19th-century fort and a cluster of colonial-era buildings in the old city centre (known as Adum). But the city boasts several worthwhile sites of interest, ranging from the Prempeh II Jubilee Museum to the sprawling and redeveloped Kejetia Market, and is also a useful base for any number of day or overnight trips into rural Ashanti.

Mole National Park

Although Mole is undoubtedly Ghana’s premier wildlife destination, its immense potential as the linchpin of the northern tourist circuit remains largely unrealised, a bizarre oversight that not only is detrimental to travellers and to regional tourism development, but also works to the probable advantage of subsistence poachers. This has improved, with the surfacing of the road to the park, long-overdue introduction of organised game drives, and the opening of Zaina Lodge, which offers a luxurious tented camp experience that’s entirely unique to Ghana and would be right at home in the parks of eastern or southern Africa. Nevertheless, as things stand, the gameviewing circuit is limited to a 40km network of poorly maintained roads to the south of the Lovi River, leaving about 95% of the park inaccessible to visitors, and the infrastructure falls below the standard normally associated with national parks in southern and eastern Africa.

Set aside as a game reserve in 1958, a year after Ghana attained independence, Mole protects a vast tract of undulating and relatively dry savannah woodland that had always been thinly populated due to an abundance of tsetse flies and lack of perennial water. It was gazetted as a national park in 1971, following the controversial resettlement of the relatively few villagers who lived within its boundaries, and was extended to its present size of 4,840km² in 1991. The park lies at an average altitude of about 150m, but is bisected by the 250m-high Konkori Escarpment, on which the Mole Motel and Zaina Lodge are situated. The two main watercourses are the seasonal Lovi and Mole rivers, tributaries of the White Volta River that seldom flow in the dry season, but feed a scattering of more permanent waterholes.

Paga

Situated 12km north of Navrongo along a good surfaced road, Paga is the most popular crossing point between Ghana and Burkina Faso, though you’d scarcely know it from the subdued mood of the rustic town centre – a chaotic northern counterpart to Aflao or Elubo it most definitely isn’t! International connections aside, Paga is best known for its sacred crocodiles, which can be seen at unusually close quarters, and form the centrepiece of a perennially popular community tourist project. Other attractions include the Paga Pia’s Palace near the taxi park and Pikworo Slave Camp 2km from the town centre.

Paga hosts some superb examples of the extended family homesteads that characterise this border region – fantastic, labyrinthine, fortress-like constructions characterised by their curvaceous earthen walls, flat roofs and cosy courtyards. Many of the complexes are more than a century old, and they may be inhabited by more than ten separate households, each with its own living quarters and courtyards, some marked by rounded mud mounds under which an important family member is buried. The flat roofs are used not only for drying crops, but also as a place to sleep in hot weather, while the mud walls are often covered in symbolic paintings or portraits of animals.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Ghana:

Related articles

How many have you visited?

With some of the largest marketplaces in West Africa, organised chaos is something of a speciality in Ghana.

Author Philip Briggs describes the unusual shrines that are a distinctive feature of Ghana’s central coast region.

Ghana’s craft highlights provide a fascinating insight into the country’s unique customs.