It’s one of the most heart-warming and exciting of all European destinations. This is above all due to its people, who are some of the most hospitable and generous you could meet anywhere.

Tim Burford author of Georgia: the Bradt Travel Guide

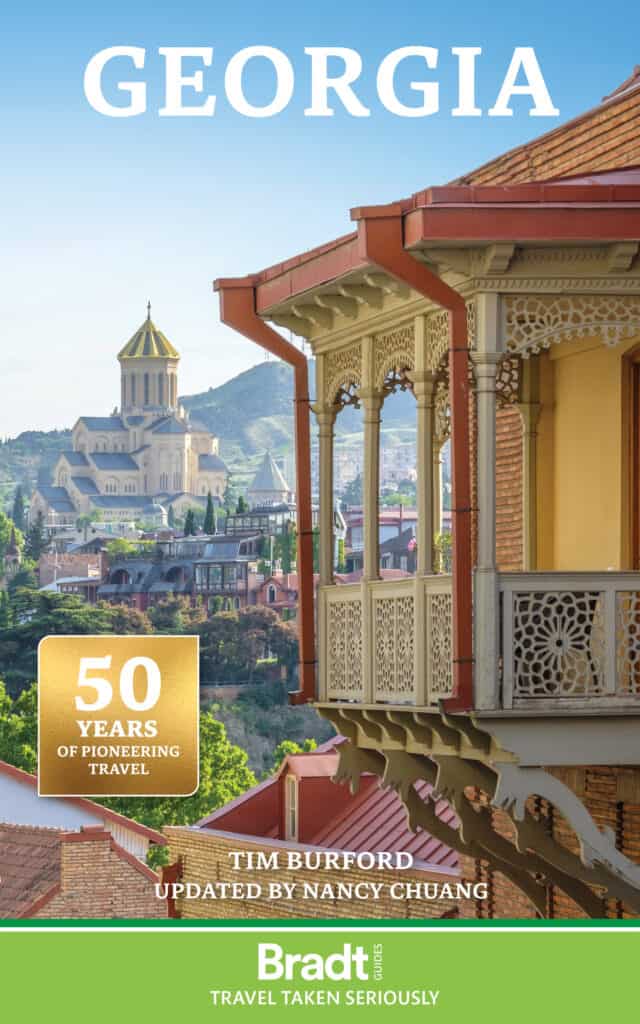

Although one of Europe’s lesser-known countries, Georgia is also one of its most captivating. Tbilisi, the stylish capital, is home to an exquisite blend of architecture, whilst sophisticated Batumi is often described as the Black Sea’s ‘Atlantic City’.

But its rural roots remain strong, and away from the cities you’ll find remote mountain villages and countless walking trails. Set against the backdrop of the High Caucasus, it’s a dreamland for any hiker or climber.

More information

For more information, see our guide to Georgia:

Food and drink in Georgia

Food

Georgian cuisine is far closer to that of Turkey and Iran than that of Russia, with plenty of garlic, walnuts, cumin and coriander; huge feasts are traditional, though not as huge as in the Brezhnev years, when food was absurdly cheap.

Meat is central, but a Georgian meal is served with many dishes (many cold), including vegetable ones, on the table at once and everyone helping themselves to whatever they want (so the concept of pairing specific wines and foods doesn’t work here).

When it comes to food and drink in Georgia, menus are rarely displayed outside restaurants, especially in English, and dishes come as and when – don’t expect a flight of orders to arrive simultaneously. It’s best to pace yourself, as it’s likely to be a long evening with plenty of wine.

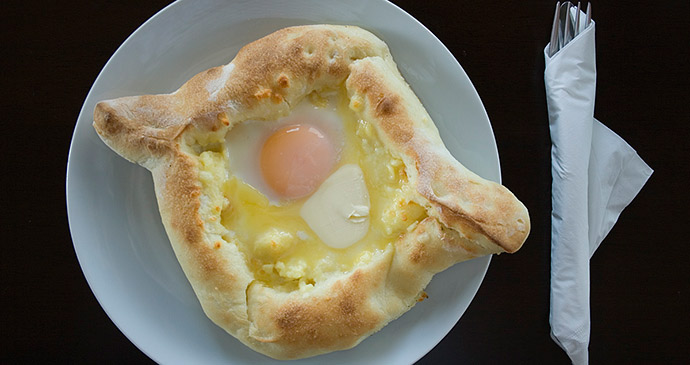

In Tbilisi there are fast-food joints selling shwarma (kebabs), burgers, hot dogs and a poor approximation to pizza. Cafes everywhere sell khachapuri and other traditional snacks. Street traders sell marozhni (ice cream) and semichki, the sunflower seeds which are chewed and spat out everywhere, and probably use more energy than they provide.

Those who would like to try their hand at reproducing some of the dishes they enjoyed in Georgia will find a wealth of inspiring and knowledgeable food and wine bloggers discovering Georgia.

Drink

Wine is absolutely central to the Georgian lifestyle and to their self-image, and everyone (especially men) drinks large quantities and will want you to do the same. In theory Georgians drink red wines in winter, and whites in summer, but in practice it’s hard to tell the difference, as even ‘red’ (literally ‘black’ or shavi) wines may in fact be straw-coloured.

There are lots of amber or orange wines, made with white varietals but with the skins, seeds and stalks left in contact for up to six months, producing something with tannin that’s more like a red and is great with food. Most families make their own, storing it in kvevri, large sealed clay vessels set into the floor of a room known as the marani. In every ancient site you visit, such as Vardzia or Uplistsikhe, there’ll be a marani or three.

Vodka is drunk in Georgia, but far less than in Russia and the other Slav countries; the national spirit is chacha, a firewater made at home, as a rule from grain, although in Svaneti, where grain doesn’t grow, they use bread instead!

Health and safety in Georgia

Health

Reform and privatisation of Georgia’s corrupt and run-down health service began in 1995; now a state medical insurance company and 12 health funds are funded by a payroll tax of 3% on employers and 1% on employees. The health service is still corrupt and run-down, but slowly improving as the economy recovers, though the share of GDP spent on health is still under 1%.

Although British citizens are covered by a reciprocal agreement and need only proof of UK residence (ie: UK passport) for free treatment, they will still have to pay cash for drugs and many other services; as a rule US health insurance is not valid in Georgia without paying a substantial premium. Treatment is expensive (US$600 for a hernia operation), and even if you can pay for it there is a shortage of basic medical supplies, such as hypodermic needles, anaesthetics and antibiotics. Embassies have lists of good English-speaking doctors in Tbilisi.

You are advised to be up to date with vaccinations against tetanus, diphtheria and polio, now available as an all-in-one ten-year vaccine (Revaxis). You should also be covered for hepatitis A and very occasionally typhoid for longer trips and more rural travel. Other vaccines that may be advised include a course of hepatitis B and rabies vaccine. Hepatitis B vaccination is essential if you will be working in a medical capacity and is usually recommended when working with children. Having the pre-exposure rabies jab is particularly important as there’s a shortage of the rabies immunoglobulin used for treatment following bites, scratches or even licks from any warm-blooded mammal. The courses for rabies and hepatitis B comprise three injections over a minimum of 21 days (for hepatitis B you need to be 16 or over for this super-accelerated course), so you should go to see your GP or travel clinic specialist well in advance of your trip.

Tuberculosis (TB) is common in Georgia with ≥40 cases per 100,000 population (Travel Health Pro, 2018). The disease is spread through close contact with infected sputum or through eating unpasteurised dairy products. Vaccination may be considered for those under 16 who are living or working with the local population for three months or more. Tuberculin-negative individuals under 35 years of age should be considered for vaccinating if they are at risk through their occupation. The vaccine becomes less effective with age, so vaccinating people over the age of 35 is considered only if they are at very high risk of disease.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on ISTM. For other journey preparation information, consult NaTHNac (UK) or CDC (US). Information about various medications may be found on NetDoctor. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Georgia is in general a safe country, with too few tourists for them to be targeted by thieves. Abkhazia, which has effectively seceded, is a little more problematic, and with no diplomatic representation you are very much on your own there if you get into trouble.

The bordering area around Zugdidi is also considered to be risky. South Ossetia is not only a problem politically, but crime levels are higher than elsewhere here too, partly due to the wide availability of guns; the same used to apply to Svaneti, where unwary tourists were almost routinely robbed until a few years ago, but this is now as safe as anywhere in the country. Nevertheless it is still probably wiser not to go walking too far outside Mestia or Ushguli without a local guide.

Tusheti and Khevsureti are also safe – they were closed to tourists due to the Chechen war but there’s no problem now. In Tbilisi, you should take the same common-sense precautions as in any other big city.

There’s little public drunkenness in Georgia, and there are usually plenty of people on the streets, even late at night; however, there have been vicious muggings of foreigners, usually in the dark entrances to apartment blocks. Otherwise, there is some pickpocketing, particularly in the metro, but few other problems.

The days of Kalashnikov-toting Mkhedrioni (political gangsters) running the whole country as one big protection racket are long gone!

Female travellers

Sexism in Georgia is as bad as anywhere in the world, but as a rule foreign women see only the positive, chivalrous side of the Georgian male’s world-view. In smaller towns and villages you may notice some stares and comments, but much less so than in neighbouring countries.

There are some notable female politicians, notably Justice Minister Tea Tsulukiani, and three former foreign ministers, Tamar Beruchashvili, Salome Zourabichvili and Maia Panjikidze, and 39% of Georgia’s judges are women. Nevertheless, the proportion of women in parliament has fallen considerably from 30% in Soviet times, hitting a low of 5% in 2008 before recovering to 12% in 2016. In 2016 just 1.6% of local councillors were women, and not a single mayor.

According to UN research, one in 11 married women in Georgia has been subjected to domestic violence; but the real number could be much higher as victims rarely speak out. Three-quarters of Georgian women believe domestic violence is a private matter and should remain within the family, and police refuse to get involved.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Despite the fact that discrimination against LGBT people is illegal, homosexuality is still viewed as a major deviation from Orthodox Christian values in Georgia – the Church itself is very anti-gay and priests have led violent protests against gay pride marches.

In a 2017 survey, Georgia was rated as the world’s third-most homophobic country, with 93% of Georgians saying they would object to having a gay neighbour. In October 2017 there were protests against Guram Kashia, captain of Georgia’s soccer team (who plays for Vitesse Arnhem), wearing an LGBTQ armband as part of a Dutch Football Union pro-diversity campaign – but the same month the first openly gay candidate stood for Tbilisi’s city council (although she wasn’t elected).

As you might expect, attitudes are changing faster in the capital than elsewhere – thanks to dating apps and inclusive nightclubs such as Bassiani, gay people there can now be much more open and confident in their identity.

Recent changes in legislation are due more to pro-Western alignment rather than any real buy-in by politicians. Nevertheless, there are a small number of pro-gay bars in Tbilisi, such as Success, Cafe Gallery, Salve and Divan. It is also normal for two men or women to share a room with each other.

Travel and Visas in Georgia

Visas

Citizens of the European Union, USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Israel and many other countries do not require visas for visits to Georgia of up to a year. Otherwise you’ll need to buy a single-entry visa at an embassy or consulate, or online. Visas are no longer issued at rail or sea entry points. Citizens of 94 countries can now stay for up to 360 days, after which you just need to leave the country and re-enter to stay another 360 days, and you’re even allowed to work in Georgia.

For further information, contact the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It’s better not to overstay – there’s a penalty of GEL190 (US$75) for up to six months beyond your visa’s expiry or GEL 360 beyond that, and you may not be allowed back for three months.

It’s easy enough to cross from Georgia to Abkhazia but you cannot travel from Russia to Georgia via Abkhazia; however, it’s not possible to visit South Ossetia or Tskhinvali for the time being. British and US embassies advise against visiting both Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

There was a great deal of petty corruption and grafting at Georgia’s borders in the past, with officials demanding a few dollars from travellers, but this has been cleaned up since the Rose Revolution. The problem now seems to be racism, with too many cases of people of colour being refused entry, even with a visa.

Getting there and away

By plane

Direct flights from London were introduced in 2017, both from Gatwick with Georgian Airways to Tbilisi and from Luton with Wizzair to Kutaisi. You can also go via Istanbul – Turkish Airlines give the most options: from Britain there are eight flights a day from London (both Heathrow and Gatwick), two from Manchester and one each from Birmingham and Edinburgh, the latter connecting with a midnight flight from Istanbul (Ataturk) that reaches Tbilisi at 04.30 (there’s also a 14.00 flight that arrives at 17.00); they also fly from Ataturk to Batumi.

By bus

Coming from Turkey, you’re mostlikely to travel by bus (the rail link from Kars to Tbilisi via Akhalkalaki opened at the end of 2017 but still has a limited passenger service). There are two main routes, along the Black Sea coast to Batumi, and by the Vale border crossing to Tbilisi; a less useful third crossing has opened at Çıldır in Javakheti. There are also minibuses and shared taxis between Yerevan (Armenia) and Tbilisi.

Getting around

By bus

The main mode of public transport is the bus. Cities have fairly substantial bus stations, while smaller places may just have a yard by the rail station or in the centre of town. Departure bays will have the destinations served written in Georgian, but if you look at the rear of this sign you may find the same information in Cyrillic or even Latin script. Comfortable modern buses run from Tbilisi to Kutaisi and Batumi. Fares are generally about GEL1 per 20km, eg: GEL8 to Lagodekhi, GEL18 from Tbilisi to Batumi or GEL10 from Kutaisi to Batumi.

By car

Driving is difficult, given the awful state of the roads and the excessive urgency of the other drivers. Self-drive car hire is not yet common, and the cost of a driver is not high, so this may be the easiest solution; in Tbilisi it’s easy to hire a taxi (including 4×4 vehicles) at the Didube bus station. The only major international car-hire chains represented in Tbilisi are Avis and Hertz, whose agents are Caucasus Travel. A licence from almost any of the developed Western countries is valid in Georgia.

Distances are not great: by road it’s about 85km from Tbilisi to Gori, 128km to Khashuri, 230km to Kutaisi and 384km to Batumi (349km by rail).

By train

There has been a remarkable revival of Georgia’s railways, making it the safest and most pleasant option for tourists travelling to the west of the country.

The tracks were previously neglected and pounded by heavy trains transporting oil from Baku, but now the pipelines are open and new trains have been introduced, in addition to the long-distance overnight trains – although there are still enough oil trains to cause delays.

The main line from Tbilisi to Samtredia is almost all double-track, and all Georgia’s railways are electrified, though at one time power cuts were causing US$30,000 of damage a month to delicate traction equipment, and causing oil trains to take an average of 35 hours from Baku to Batumi instead of the scheduled 21 hours. Now, new day trains run from Tbilisi to Batumi (5hrs), Poti (4hrs 5mins), Ozurgeti (8hrs 10mins) and Zugdidi (5hrs 25mins).

When to visit Georgia

Georgia may not suffer so much from energy shortages these days, but winter is still not the smartest time to visit, unless you are just interested in Tbilisi and the ski resorts. High summer can be too hot and humid, but spring and autumn are ideal times to visit; in particular the golden autumn colours can be spectacular, and the wineharvest makes this a great time to visit Kakheti; however, beach resorts such as Kobuleti close by the end of September.

Climate

There’s quite a wide range of climates in Georgia, from the warm, humid, subtropical Black Sea coast, via the colder, wet, alpine climate of the High Caucasus, to the arid steppes of the east.

Temperatures in the mountains range from an average –4.6°C in February to 16.4°C in July and August. In Svaneti the winter lasts for up to eight months, with an average temperature of –15°C; it gets even colder on the high bare plateaux of Javakheti where temperatures drop to –30°C. On the coast of Adjara, average temperatures range from 5.8°C in January to 23.8°C in August; on the Abkhaz coast temperatures are slightly lower in winter, noticeably warmer in April and May, but virtually the same in high summer. In eastern Georgia temperatures range from 0.5°C in January to 23°C in August, and in the south they range from –2.1°C in January to 20.1°C in August.

The weather in the Caucasus is more stable than in the Alps. In June there may still be too much snow for high hikes; July and August have the best weather, but even then it can drop to –10°C at 3,000–3,500m. Lower altitudes can often be hot and humid at this time of year, and the inhabitants of Tbilisi and Kutaisi flee to the coast or the mountains.

Precipitation ranges from 2,800mm in Abkhazia and Adjara to 300–600mm in the east (with 462mm in Tbilisi), and about 1,800mm at the main Caucasian passes. There’s an average of 1,350–2,520 hours of sunshine per year (3 hours a day in December, over 8 hours from June to August) in Tbilisi.

What to see and do in Georgia

Batumi

Batumi, with its sheltered natural harbour, existed as a Greek trading colony by the start of the 2nd century BC at the latest. Under Turkish rule it was never anything more than a tiny fishing village, but once the Russians arrived in 1878 it began a very rapid development.

Now it’s a city of around 130,000 people, and handles a great deal of trade with Turkey, both by land and sea. Its name is probably derived from the Greek words bathys limen (deep harbour).

From 2009, the Saakashvili government used an array of incentives to trigger a building boom aimed at turning Batumi into the Las Vegas of the Black Sea.

The new architecture is glitzy, verging on kitsch, particularly around Evropus Moedani (Europe Square) and especially all along the seafront, from the towers in Miracle Park to the New Boulevard well south of the city.

The Sheraton and Radisson hotels, built in 2010 and 2011, are now dwarfed by the Porta and Technical University towers, although plans for Donald Trump to co-finance, with the Silk Road Group, a Georgian ‘Trump Tower’ development have so far come to nothing.

The city is a popular destination for Turks, Arabs and Iranians, and their languages, and Russian, are more obvious here than English – whereas Tbilisi seems to be oriented towards Europe, Batumi is closer to Beirut or Dubai.

In 1990 the city covered 18km2, but it now sprawls over 65km2, with very high levels of car use and just 0.3% of the population cycling, and unsurprisingly congestion and pollution have become serious problems; a Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan is being developed, and cycle lanes are appearing across the city.

Borjomi

Just before km29/68 the main road up the left/west bank of the Mtkvari reaches the centre of the spa town of Borjomi, with shops, a market, and a bus station, just south of the centre.

One of the main attractions here is Borjomi spa, which, at an altitude of 800m, offers both health-giving waters and a bracing mountain atmosphere. Chekhov, Tchaikovsky, members of the Romanov family and Stalin were among those who came to take the waters here.

Inside Ekaterina Park, a covered pavilion has taps spewing out the famous Borjomi water. Together with Narzan (from the northern Caucasus) this was the former Soviet Union’s favourite mineral water, with 300 million bottles a year being filled when times were good.

It’s flavoured with sodium carbonate, tasting something like Vichy water – slightly warm and salty. The park was refurbished in 2005, and now has a modern pool near the entry, as well as restaurants, bars and a cinema.

The Borjomi-Kharagauli National Park marks the division between the humid Colchic habitats of western Georgia and the drier landscapes of the east. There is an intriguing mix of species here, as well as Tertiary relics and some endemic species (such as Gladiolus dzavacheticus and Corydallis erdelii).

The area became a nature reserve in 1935 and a national park in 1995, opening to the public only in 2001. The park covers 85,000ha with a buffer zone of 450,000ha, and includes Sametskhavareo, the highest peak in the region at 2,642m.

Davit-Gareja

In virtual desert on the Azerbaijani border is the Davit-Gareja complex of monasteries, a group of cave monasteries founded in the mid 6th century by St David (one of the 13 Holy Assyrian Fathers), and his disciple Lukian, after his stay on Tbilisi’s Holy Mountain. Over 20 monasteries have been identified, but only a few are widely known or visited.

There’s no way to get here other than by mountain bike, car or a trip organised by a tourist agency; it’s about 70km, or under 2 hours, each way from Tbilisi. A day trip costs around GEL150 for two people, or about half that if you have your own car; if not you’ll usually be accompanied by both a driver and a pretty knowledgeable guide.

From mid-April to early November a minibus operated by Gareji Line leaves daily at 11.00 from the Pushkin statue near the northeastern corner of Freedom Square in Tbilisi, stopping for lunch at the Oasis Club, then visiting the monasteries for about 3 hours and returning after 19.00.

If you’re thinking of moving from Tbilisi to a hotel in Sighnaghi or Telavi, ask about a transfer including the detour to Davit-Gareja, which makes a very cost-effective combination. A cheaper but fussier way to reach the monastery complex from Tbilisi is first to take a marshrutka to Gardabani or Sagarejo, then hire a taxi for the round trip from there. This does involve far more hanging around at bus stations, however.

Don’t be tempted by the daily bus to Udabno village, it’s tiny and you won’t find a taxi to get to the actual monasteries. There’s no government involvement at all, with lots of graffiti, bad paths and no safety warnings; it’s not at all easy for the elderly or less able to reach Udabno Monastery or enter the caves. Two hours is enough time to see the Lavra and Udabno monasteries.

Kazbegi

This is the only town in Khevi province (or Mokhavia) and the only place with anything resembling shops and accommodation. However, with a population of just 4,000 and relatively little through traffic to Russia, commercial opportunities are inevitably limited, although it’s worth looking for the local woollens, such as socks and hats.

It’s a small, sleepy place, dominated by free-range highland cattle and pigs. Known in the 19th century as Stepan-Tsminda (St Stephen), the town was then named after Alexander Kazbegi (or Qazbegi; 1848–93), a local noble who became a much-loved pastoral poet, living as a shepherd for seven years; it has now reverted to Stepantsminda, but Kazbegi remains the more widely used name.

The square, dominated by a monument to Kazbegi, is lined with 4×4 taxis and marshrutkas, as well as a couple of cafés and hotels. There are opportunities for outdoor exploration here, including exploring the Kazbegi Nature Reserve, doing the Gergeti Hike, and climbing Mount Kazbek.

Kutaisi

Kutaisi dates from perhaps the 17th century BC and was established as the Greek colony of Aia (still the name of the city’s football team) by the 7th century BC; it was the capital of Colchida (and thus the birthplace of Medea) from the second millennium BC, and from AD978 to 1122 capital of the united Georgia, Tbilisi being occupied by the Turks.

It was again capital of Imereti from the late 15th century to 1810. Kutaisi was spared by the Mongols, but was burnt by the Turks in 1510, 1666 and in 1692; they were driven out in 1770 by Solomon I.

Under communism it grew to be a city of 240,000, but its main employer, the Kamaz truck factory, soon closed and the city became the mafia capital of Georgia and perhaps the whole former Soviet Union.

It has long since been cleaned up and may be revived by the National Parliament moving to Kutaisi, although little actually happens in the flashy new building other than voting; the real work is apparently still done in Tbilisi. Its population has now dropped to 150,000, a couple of thousand fewer than Batumi.

The city’s great sight is the Bagrat Cathedral. It was commissioned by Bagrat III in 1003 as a huge triconch cruciform church with a central dome. The cathedral was destroyed in 1691–92 by the Turks, leaving it roofless; it was disused, but immensely impressive, until 2008, when President Saakashvili launched a controversial plan to restore it as a working church. UNESCO, which had placed it on its World Heritage List in 1994, was very opposed to this (along with many other people and bodies) and in 2010 placed it on its list of World Heritage Sites in Danger.

However, Saakashvili pressed on, owing to its importance as a symbol of national unification having been built by the first ruler of a united Georgia. The restoration is now complete, with a horrid green roof and a modern tower discreetly added on the north side, and UNESCO has now removed the cathedral from the World Heritage List.

There are other interesting churches to the east of the centre, such as the Church of the Annunciation of the Virgin. This is a Georgian Orthodox church, with an interior that seems at odds with its Baroque exterior and Latin inscription.

It is worth making the excursion from Kutaisi to Gelati. Wonderfully set in the hills just to the north of Kutaisi, the monastery of Gelati is one of the most beautiful spots in Georgia. The centrepiece is the great Cathedral of the Virgin, built by King David the Builder in 1106–25 (though in a style typical of the 11th century).

Burnt by the Turks in 1510, and by the Lesghians (from the north Caucasus) in 1579, it was restored, then closed under communism, and reopened in 1988. The interior is full of light, and painted in fantastic colours (although a blue background is unusual in Georgian churches).

Svaneti

Svaneti, the land of the Svans or Svanebi, hidden in obscure recesses of the High Caucasus, is an area to which much mystery attaches itself.

It’s seen as more Georgian than Georgia proper, the repository of the country’s soul, due to having been the last refuge from the Mongols – the holiest icons and richest treasures were carried up beyond the Enguri gorges for safe keeping in times of crisis, and artistic and religious traditions are felt to have been better preserved here than elsewhere.

At the same time the Svans are seen as strong but unsophisticated, often disregarding the norms of law and order and speaking a language which split from Georgian by the 6th century and is largely incomprehensible to the people of Kartli and Kakheti.

The Svans’ fearsome reputation for brigandage is not wholly without foundation; indeed crime flared up during the Shevardnadze period, and during the civil war in Abkhazia, when refugees were fleeing from the Svan-populated upper reaches of the Kodori and Sakeni rivers, some were greeted by soup kitchens at the passes, but others were robbed by their fellow Svans.

Until 2003 tourists were sometimes held up and robbed here but the situation changed dramatically thanks to investment and a clean-up campaign by President Saakashvili.

The typical Svan name ‘Kurdiani’ means ‘thief ’, although the family has actually produced many well-known Tbilisi architects and artists. In fact, the Svans are very hospitable and friendly, and given the amazing beauty of the surrounding peaks, the clusters of defensive towers that dominate the villages, and the frescoes and icons of the churches, it is hardly surprising that these valleys are now enticing many visitors, just as in Soviet times.

More and more independent travellers are arriving and people can see the economic benefits of tourism: the total was still only 1,200 in 2005 but now an estimated 50,000 visit per year. The Saakashvili administration sought to develop tourism in Svaneti even further, turning the region into a ‘Switzerland in the Caucasus’, complete with ski slopes and modern hotels.

One aspect of this was the enlargement of Mestia’s airport to handle commercial flights. Another is the US$25 million spent in 2011 on rebuilding the rough, and occasionally frightening, 136km highway between Zugdidi and Mestia, built only in 1934; journey time was cut from 6 hours to just three.

Such changes will undoubtedly boost the region’s economy, although the harm they will do to an age-old and formerly isolated culture such as this remains to be seen. The Svan culture is probably strong enough to survive, but it’s still sound advice to get there as soon as possible.

Tbilisi

Tbilisi lies at about 380m altitude, on the same latitude as Rome, Barcelona, Boston and Chicago. It stretches for 20km along the River Mtkvari (the Kura in Russian), with mountains on three sides: Mtatsminda to the southwest, Mount Tabori and the Solalaki Ridge to the southeast, and the low undulating Makhat Ridge to the northeast, beyond which is the so-called Tbilisi Sea, now a reservoir, and then the Samgori steppe.

Republic Square (now officially known as ‘Rose Revolution Square’) has plenty of restaurants, bars and cafes in its immediate vicinity. Many of Tbilisi’s most popular bars can be found along Akhvlediani Street (still best known as Perovskaya) and Kiacheli Street. Most of them offer food of some type, although it tends to be a featureless blend of Georgian and international styles.

The Old Town of Tbilisi (the Maidan or Kala) lies higgledy-piggledy on the crowded slopes between the river and the citadel of Narikala. Here, in an area inhabited, at various times, by Persians, Tatars, Jews and Armenians, you can visit a mosque, a synagogue, and Armenian and Georgian churches, all still in use.

The Carvasla, built in 1650 as a trading centre for visiting merchants then rebuilt in 1912 with an Art Nouveau facade, now houses the Museum of the History of Tbilisi. The interior seems like classic 1980s architecture, in fact very similar to the Metechi Palace Hotel, with a high atrium and three galleries overlooking a cafe by a fountain, which was once a drinking pool for pack animals. If you happen to pass its rear, on the Mtkvari embankment, you’ll see two sculpted griffons, with three of their four wings missing.

The Sioni cathedral is a typical domed Georgian church built in the 13th century of tuff stone from Bolnisi, and nothing special architecturally. However, it is the centre of religious life in the city, partly due to the presence of St Nino’s cross, which she made by binding two vine branches together with her own hair (hence the drooping arms of the Georgian cross); a replica is displayed to the left of the iconostasis, but it’s hard to see much as even this is in an ornate early 14th-century reliquary.

Nowadays Tbilisi is far more crowded and hectic than it was then, but its mix of ancient churches next to hip restaurants and of old ladies in black shuffling home from the market alongside young people with ripped jeans and the latest phones give the city a very specific allure.

Tusheti

ust beyond Alaverdi, on the far bank of the Alazani, is Kvemo (Lower) Alvani, a village which in summer is very quiet but in winter acts as home to the bulk of the population of Tusheti, on the far side of the Caucasus watershed. It’s the starting point for travel to this wonderfully remote and scenic area. It’s also the administrative centre for the Tusheti National Park, which comprises a total of 16,297ha in the Tushetis, Batcharis and Babaneuris reserves.

In the Batchara Gorge, north of Akhmeta, there’s a unique forest of yew trees, up to 25m high, 1.2m in diameter and 2,000 years old; this is currently inaccessible due to the problems in the Pankisi Gorge, immediately adjacent.

The Babaneuris Reserve, just northeast of Kvemo Alvani, has yews about 1,000 years old, from 950m to 1,350m altitude. The Tushetis Reserve protects possibly unique virgin forests of pine (2,000–2,200m) and birch (2,300–2,600m). Although the national park is still relatively new, it has managed to support a number of guesthouses in Omalo and Dartlo.

The region of Tusheti was effectively autonomous as a tribal democracy until the end of the 17th century, and a road was not built here until 1978–82. Until the 1940s people here had a totally self-reliant life, growing enough wheat, hops and potatoes to keep them through the winter; they then tried to declare independence from the Soviet Union but were crushed by the Red Army, the men being sent to the army or the gulag and the women and children deported to Alvani, since when they have lived a seasonally migratory life.

The scenery is almost as spectacular as in Svaneti, with peaks up to 4,500m, deep gorges and high waterfalls, and well preserved pine forests of Pinus kochiana. It’s similar in many ways to Svaneti, with traditions of hospitality coupled with building spectacular defensive towers or koshkebi; but, unlike Svaneti, there were never any reports of robberies here.

There’s also plentiful evidence of the survival of animist religion here, with the horns of sacrificed goats or sheep placed on stone shrines or khatebi close to most villages – women are not permitted to approach these shrines (although photography from a distance is fine).

Tusheti delicacies include kotori, a bread with a cheese and potato filling, the hard, dry kalti cheese, the smoked cottage cheese-style dambal kacho and very salty gudiskweli or chogi cheese, made of sheep’s milk in a bag (guda) of sheepskin, with the wool on the inside. In 2017 the top prize at Slow Food’s International Cheese Festival in Italy was won by a guda (not Gouda) cheese from Tusheti. Pork is forbidden in Tusheti – in fact local people won’t eat it the day before they travel to Tusheti as it will still be in their gut.

Uplistsikhe

About 10km east of Gori along the Mtkvari Valley, visible from trains along the main line, is the cave-city of Uplistsikhe. The Silk Road ran along the hills to the north (hence the positions of Gori, Kaspi and Mtskheta, all on the north side of the Mtkvari), and excavations in the area have shown evidence of settlement from the second half of the 4th millennium BC onwards.

Uplistsikhe was a religious centre by 1000BC (its temples dedicated mainly to the sun goddess) and a trading centre by at least the 5th century BC. Later it became more isolated and was inhabited by monks until it was destroyed in the 13th century by Chinghiz’s son Khulagu. Most of the caves have been at least partly eroded away, so that it takes a considerable feat of the imagination to really understand what the city was like.

Over the centuries the site has suffered greatly from the elements, although channels were built to carry off storm water and prevent flash floods (drinking water was brought 5–6km from a spring just 44m above, through a beautifully engineered system of ceramic pipes and a tunnel). In addition, cracks are developing in many of the caves, which may crumble away in the next ten to 30 years unless action is taken.

The tour of the ruins is only for the able. Start by scrambling up rocks past grain pits to the remains of a theatre built in the 2nd or 3rd century AD, complete with orchestra pit; the auditorium side has now all collapsed into the river and been washed away, and the stage roof is held up by concrete pillars. There’s even a bread oven in the middle of the stage.

The largest hall in the city is known as Tamar’s Hall, although Queen Tamar never lived here; its front wall has gone, but it’s otherwise intact. The marani (wine-storage room) next to it, one of three in the city, dates from after her time.

There’s an underground prison, 8.5m deep, just below Tamar’s Hall, and to the south is what must have been a pharmacy, with eight layers of storage spaces (about 15cm cubes), where traces of herbs and wrapping parchments have been found. To the north of Tamar’s Hall is another hall, now roofless, which was once a church – there’s very little left except for the stumps of four columns, and a basin for the blood of sacrificed animals.

Further up there’s a very obvious conventional church, a three-nave basilica built of red brick in the 9th–10th centuries, which survived the Mongol onslaught, although all 5,000 resident monks were killed. The church’s frescoes were all whitewashed in the 19th century.

On the way back down you’ll pass the market, with its stone stalls, and may finish by going down through a 41m tunnel (designed to be used by water carriers) to exit on the track beside the river. This leads to a village immediately to the west, whose inhabitants were removed in 1968 (though at least one house is clearly in use again).

You might be tempted to set out to walk back to Gori along the north bank of the river, but you should be aware of the deep gullies blocking the way.

Vardzia

Having been in a closed border zone throughout the Soviet period, Vardzia is now receiving plenty of visitors, especially in summer. It’s said that its name derives from ‘Ak var, dzia’ or ‘Here I am, uncle’ – Tamar’s call when lost in the caves.

First established by King George III in 1156 and consecrated in 1185, his daughter Tamar made it into a monastery, which became the chief seminary of southwestern Georgia (housing 2,000 monks) until an earthquake ruined it in 1283, slicing away a large portion of the rock face.

Another quake in 1456 was followed by a Persian army in 1551 and the Turks at the end of that century, so that now around 600 chambers survive of a total 3,000, which included stables, barracks, bakeries, wine presses and stores. Likewise, only half a dozen levels remain of the 13 which once penetrated 50m into the cliffs.

Below the cliffs is a bell-tower (built after the 1283 earthquake), the refectory, and the Church of the Assumption (1184–86), the pivotal point of the complex. This contains a famous fresco of Tamar (one of just four painted in her lifetime) and her father, together with what seems to be an Annunciation but for the fact that the Virgin already has the child Jesus on her knee. Down a dark tunnel is the pool known as ‘Tamar’s Tears’, where the water is beautifully cool and sweet.

Returning outside, you can explore the rest of the city more or less at random; some of the chambers are interconnected, but thanks to the earthquakes most of them are now open to the outside world. There are a few frescoes, although most of the chambers are smoke-blackened; what are more interesting than the walls and ceilings are the floors, which are pitted with a surprising array of channels and receptacles for water and, of course, wine.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Georgia:

Related articles

This isn’t one for claustrophobes.

Discover our favourite sights along one of the most important trading routes in history.

From its array of traditional markets, to its selection of historical museums, Tbilisi offers the perfect choice for travellers seeking a weekend of culture.

From delicately built churches to cave-city complexes.

From stunning landscapes to sites of historical and cultural importance, monasteries provide a wealth of interest for the avid traveller.

Boasting a delightful old town, a handful of Soviet relics and a vibrant alternative arts scene, Tbilisi is a city of contrasts, and one worth exploring.

Although one of Europe’s lesser-known countries, Georgia is also one of its most captivating.