Travel in the Land of Snows is a guaranteed adventure, with the wildest routes in High Asia. Its combination of extraordinary landscape, extraordinary people and high adventure makes Tibet special.

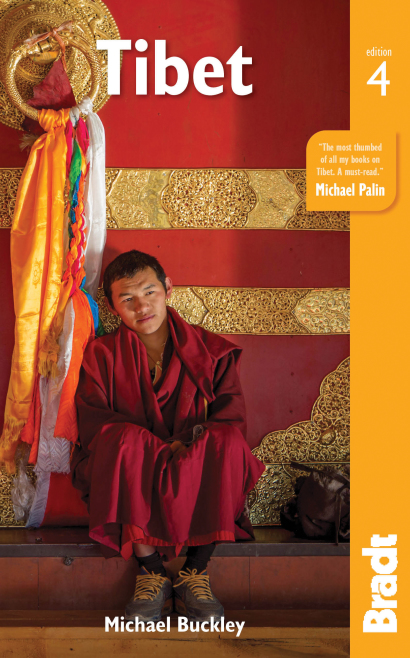

Michael Buckley author of Tibet: the Bradt Guide

Tibet is a land of superlatives – with the world’s highest peak (Everest), the world’s deepest gorges (Yarlung Tsangpo), the most sacred peak in all of Asia (Mount Kailash), and arguably the most spectacular road route in the world (Lhasa to Kathmandu). Nevertheless, the country has always been a tough place to access.

Tibetans themselves closed their nation off to foreigners for centuries. Then, with their invasion in 1950, the Chinese blocked foreigners from visiting. Being closed to outsiders so long, Tibet harbours many riddles – and it is only in recent decades that some of these riddles have been solved. But all of this just adds to the region’s charm and appeal.

Travel in the Land of Snows is a guaranteed adventure, with the wildest, roughest road routes in High Asia. Tibetan Buddhist monasteries blend into the landscape, becoming navigation landmarks; imposing fortress ruins cling to sheer hilltops; nomads herd yaks in snow-dusted pastures; pilgrims prostrate their way across the land to reach the sacred city of Lhasa. It is this combination of extraordinary landscape, extraordinary people, and high adventure, including iconic treks like the Everest Base Camp trek in Nepal, that makes Tibet and the surrounding Himalayas so special.

A visit to Tibet is a strange experience, with intense emotional highs and lows. It’s weird because the real Tibet no longer exists. Since their military occupation in 1950, the Chinese have systematically dismantled the Tibetan social fabric, destroyed its great monasteries, persecuted its monks and nuns, forcibly resettled its nomads in housing ghettos, and wreaked devastating damage on Tibet’s pristine environment. Any description of present-day Tibet and Tibetan culture must be framed in this context of iron-fisted Chinese occupation.

‘Intense’ is a word that applies to many aspects of Tibet. It applies to the amazing resilience of the Tibetan people in the face of extreme adversity. Their battle has been largely a pacifist one, of suffering and enduring – a game of ultimate patience and tolerance. ‘Intense’ captures the feel of the landscape. The intensity of colours at this elevation is extraordinary, with glacial-blue lakes, luminous-yellow fields of mustard, deep reds and browns of barren rock landscapes, and then, up on the horizon, looms an ethereal Himalayan snow cap, backed by piercing blue skies. The colours practically glow: when you show photographs of these landscapes to people who haven’t been there, they question the unreal colours – what kind of filter did you use?

There is only one drawback to visiting Tibet: you can easily become addicted to the place. It makes you reluctant to leave, and as you do, you’re already plotting your return – a return not necessarily to Tibet itself, but to Tibetan culture. Sadly, real Tibetan culture is more likely to be found outside Tibet, in places where refugees continue their Buddhist practices, festivals and way of life in exile – in India, Nepal and Bhutan.

Travel to Tibet raises important ethical questions. One of the biggest is: should you go? Should you put money in Chinese coffers, thus indirectly subsidising Chinese military bills in Tibet? Most of the tourist business is in the hands of the Chinese, and some of the travel agencies are run by the military. This raises the thorny question of lending legitimacy to Chinese government operations by visiting, but more important for the Tibetans is the moral support they get from visitors. Your mere presence in Tibet provides a ‘buffer zone’ in an ugly situation between Chinese and Tibetans.

Tourists love monks. This is one of the great anomalies of tourism in Tibet: the monasteries are kept open and operating because of tourist demand to see them. Apart from Himalayan landscapes, the main tourist ‘attraction’ in Tibet is its monks and monasteries, its Buddhist rituals and sutra-chanting. The Chinese really have no difficulty with this – they simply cash in on it. Apart from making a buck out of Buddhism, the Chinese have absolutely no interest in Tibet’s rich culture, its religion or its language. If you go, you line the pockets of Chinese travel agents, hoteliers and airline agents, but if you stay away, you isolate the Tibetans.

The position of the Tibetan exile leadership is to encourage tourism. Addressing this ethical dilemma – to go or not to go – Nobel Peace Prize laureate the Dalai Lama responded to a question posed in Vancouver, Canada, in September 2006, about repression in Tibet: ‘I think you must go [to Tibet] yourself, and spend some time, not only in towns but in the countryside. Go to the countryside, and with a translator, if possible one who speaks Tibetan, if not, then one who speaks Chinese. Go there. Study on the spot. Then I think you will get a real answer.’ He knows that any Western visitor to Tibet will learn of conditions there and of the aspirations of Tibetans, will not fail to be moved by the experience, and will keep the Tibetan issue alive.

The Western tourist trade in Tibet represents a small fraction of the number of visitors going to China. By far the biggest group visiting Tibet is Chinese tourists, flocking to see this exotic corner of the Motherland. According to Chinese figures, over 20 million tourists visit Tibet annually – most of them domestic tourists from big cities like Shanghai, Beijing or Guangzhou. That number is highly exaggerated because the same tourists are counted several times in different locations like Lhasa, Shigatse or Everest. By the year 2020, China expects upwards of 35 million tourists a year to visit Tibet. This gives some idea of the invasive scale of Chinese tourism – the idea is to flood the place. Tourism is a mainstay of the economy in Tibet. Basically, whether you go to Tibet or not comes down to a personal choice, to be weighed by each traveller. If you can resolve the question of ‘should you go?’, the next thing to consider is ‘can you go?’ The Chinese are suspicious – with good reason – of the activities of independent travellers in Tibet, and have shepherded visitors into monitored, higher-paying group tours. Since major upheaval and large-scale protest across the entire Tibetan plateau in 2008, foreign visitors have only managed to gain access to Tibet on group tours. There are ways around this –particularly by visiting the eastern regions of Kham and Amdo, where such travel restrictions do not apply.

For more information, check out our guide to Tibet

Food and drink in Tibet

Tibet is not noted for its culinary arts. China, however, is – ergo, find a Chinese-run restaurant if you want more variety. There’s lots of variety in Lhasa – Tibetan, Chinese, Indian, Nepalese and Western cuisines are all available. On the streets you can find fresh fruit and vegetables in abundance, and fresh bread and tangy yoghurt. You can even get good fresh cheese imported from Nepal. Yak cheese is excellent, but only when made with Swiss or Norwegian technology (as it is in Bhutan, Nepal and in parts of northern India). There are some small cheese-making concerns in Lhasa that employ European technology, but more commonly what you’ll find on sale are small pieces of rock-hard yak cheese, strung together like a necklace. These are almost impossible to eat, and are treated like sweets by the nomads, who suck on the pieces all day.

Tibetans are more inclined to run teahouses with low carpeted tables, which serve tea and momos (meat dumplings) and perhaps the odd potato. They offer lots of atmosphere, but not a whole lot of food. Lhasa is fine for food and so is Shigatse, but once out in the countryside, it’s pretty much just noodles. In the wilder areas, it’s tsampa (roasted barley flour) all the way. Tsampa is boring but quite sustaining, and you can mix it with soup or noodles (some connoisseurs add powdered milk or other substances to this Tibetan goulash).

Not many travellers take to tsampa, though more take to army-ration biscuits. Chinese packaged goods are not much more appetising. Olive-green army cans with stewed mandarins or pork or something equally disgusting are resold on the black market. When travelling in Tibet, you should always bring along some food as a backup, for the times when you’re stuck. You can load up in Lhasa on packaged soup and so on. Some bring in freeze-dried food from the West.

Bottled mineral water is available in Lhasa, Shigatse and larger towns in Tibet, where brands include Tibet Magic Water and Potala Palace Mineral Water. Cheaper than bottled water is Chinese beer. Since beer goes through a fermenting process, it’s safe to drink, but this is not advisable at altitude until you’ve acclimatised (beer should not be drunk if you have the runs, either). Available Chinese brands include Huanghe (Yellow River), Lhasa Beer, Snow Beer and Pabst Blue Ribbon.

Tibetan fusion

Tibet is not famous for its cuisine. As anyone who has attempted to choke down a few cups of yak-butter tea can tell you, this drink is an acquired taste. And yet, paradoxically, yak-butter tea contains all the ingredients needed to counter altitude. It has a high fat content to counter the cold, and it has salt to restore hydration. It is healthy, but it could take a long time to get used to that rancid yak butter floating around.

Here’s the thing: your taste buds don’t work as well at altitude. The air is cold and very dry – and when the air lacks humidity, your nasal passages, mouth and throat lose their moisture, impairing your sense of smell and taste. At extreme altitude, everything tastes terrible – or else appears to be lacking in taste. Your perception of salt can drop by as much as 30%, while sugar perception dulls by up to 20%. But not all food turns out the same way. Some tastes actually improve at altitude. Airlines have discovered that flying along in a cabin pressurised to 2,000 metres, passengers develop a sudden craving for tomato juice – because it actually tastes better in the air than on the ground. Something to do with greater acidity. Certain red wine vintages do well at altitude, while others do not.

In 2017, Hong Kong-based Cathay Pacific introduced Betsy Beer, touted as the world’s first hand-crafted beer designed to be enjoyed while cruising above the clouds at 11,000m. Heavens to Betsy! Among the ingredients is Dragon-Eye fruit, known for its aromatic properties, New Territories-sourced honey, and Fuggle, a hop that is a mainstay of British craft ales.

The most memorable dish I have ever eaten in Tibet was a plate of golden mushrooms that appeared in a humble restaurant in the middle of nowhere, was lightly cooked in sauce, and tasted fabulous. After that, I sought out these wild mushrooms in markets to buy, and would take them into a restaurant kitchen to have cooked up. There is tasty Tibetan food out there – especially when liberally interpreted by others, in India, or in the West. Here are some Tibetan fusion ideas.

Yak pizza

On travels in Tibet, you will inevitably come across yak burgers (a matter of time before someone opens a chain called YakDonald’s), yak sizzler (yak steak sizzling on a wooden platter), braised yak ribs, and yak-meat momos. In Tawang (India) you may be served yak-meat stew flavoured with spices and stinky fermented yak cheese that is aged several months or years. But here’s another combination to consider: yak pizza. Want some yak cheese with that? Or olives? It opens up a whole realm of possibilities. When it comes to yak fusion, China has never been short on ideas for medicinal variations said to cure various ailments – cooking up yak tongue, braised yak hooves (don’t ask), and yak-penis soup (definitely don’t ask).

Yak cheese, European-style

Cheese addicts will be ecstatic to learn that Swiss-style yak cheese is made in Langtang, Nepal. Huge barrel cheeses are said to be connected to a Swiss NGO aid programme. This nutty-tasting cheese finds its way to Kathmandu and Lhasa and is highly nutritious, being rich in protein because yaks eat a much wider range of herbs and grasses than cows do. Also, up Langtang way is a small operation run by Francois, who heads up Himalayan French Cheese. He produces a small yak cheese in the foothills and is working on making yak feta. He also thinks yak blue is going to work. That’s right – a stinky blue yak cheese.

Vodka butter-chicken momos

When momos, the dumplings that are Tibet’s original fast food, crossed over the Himalayas to India, some weird things happened. Chefs in Delhi and Mumbai began experimenting, catering to fussy palates, and branched out with paneer momos, Mongolian momos, Afghani momos, Punjabi momos, and Mexican-style momos. Pineapple momos are popular in Mumbai. So are shitake momos. Taking the momo to dizzy new heights, a Delhi restaurant came up with a recipe for vodka butter-chicken momos. Vodka is kneaded into the dough and added to the filling of butter chicken. And in Mumbai, a chef has come up with a momo burger, which sees several momos placed between buns, slathered with red sauce, coriander sauce and mayonnaise.

Tsampa super-soup

Tsampa, the roasted barley-flour staple of Tibet, is highly nutritious but tastes very bland. Some might say it tastes awful. Solution: add it to thukpa (Tibetan soup) to thicken the soup. While on Himalayan expeditions decades ago, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard discovered his sherpas relied totally on tsampa while on expeditions, turning their noses up at his donations of freeze-dried food. The sherpas would rehydrate their tsampa with boiling water, spices and yak butter to make a basic soup. Years later, Chouinard experimented and came up with some tasty variations on tsampa, by adding powdered soup, salmon jerky, parmesan and olive oil to the mix. This is sold by Patagonia Provisions as a kind of freeze-dried food. Or just bring your own parmesan and cans of olives into Tibet, and the tsampa might just work.

Health and safety in Tibet

Health

Some important facts to know before you go: Tibetan and Chinese hygiene standards are very poor, and Chinese medical facilities within Tibet are extremely limited. Some conclusions to draw: you may have to be your own doctor in Tibet, you have to be willing to help fellow travellers in dire situations, and you have to be prepared to evacuate if the need arises.

Prior to departure, go and visit your local health unit or travel clinic and get an armful of relevant shots. You would be wise to be up to date with tetanus, polio and diphtheria (all ten-yearly), typhoid and hepatitis A (Havrix Monodose or Avaxim). You would also be wise to consider rabies vaccine for even short trips as there is a shortage of treatment if you have not had pre-exposure vaccine before an incident. For longer trips (four weeks or longer) consider hepatitis B. Both rabies and hepatitis B involve three doses of vaccine, which can take up to two months to give depending on the age of the traveller.

Travellers going to western Tibet should consider vaccinating against tickborne encephalitis. Two doses of vaccine are ideally given at least a month apart but can be given at a two-week interval if time is short. The third dose is given 5–12 months later if you are at continued risk. Talk to your doctor and arm yourself with drugs – Azithromycin or Ciprofloxacin (antibiotics for diarrhoea or respiratory problems), Tinidazole (for giardia or amoebic dysentery) and Diamox (to prevent altitude sickness). Assemble a good medical kit. Check out where your embassies lie in China and in the neighbouring region – note down the addresses and contact numbers. Bring a health certificate to China (it may be checked). Find out your blood group and record it on that document.

Altitude sickness

When Sherpas say climbing is in their blood, they may mean it literally. Sherpas have a physiology adapted to the high-altitude environment –their blood has a higher red-cell count and their lung capacity is larger. Ability to adapt to altitude is thought to be in your genes. That may mean you either have the high-altitude genes or you don’t. If you do, you can adapt quickly; if you don’t, it will take longer – or so the theory goes. At higher altitudes, air pressure is lower and the air is thinner. Although it contains the same percentage of oxygen as it does at sea level, there’s less oxygen delivered in each lungful of air. So you have to breathe harder, and your body adapts over time by increasing the number of red blood cells enabling more oxygen to be carried through the system.

Altitude sickness is something of a mystery. It does not appear to depend on being in shape: athletes have come down with it, and it may occur suddenly in subjects who have not experienced it before. Altitude sickness can occur at elevations above 2,000m, and about 50% of people will experience some symptoms at 3,500m. The higher you go the more pronounced the symptoms could become. So adjustment is required at each 400m of elevation gain after that.

Terrain above 5,000m (common enough in Tibet) is a harsh, alien environment – above 6,000m is a zone where humans were never meant to go. Like diving at depth, going to high altitudes requires special adjustments. To adapt, you have to be in tune with your body. You need to travel with someone who can monitor your condition – and back you up (get you out) if something should go wrong. Consider this: if you were to be transported in a hot-air balloon and dropped on the summit of Everest, without oxygen you would collapse within 10 minutes, and die within an hour. However, a handful of climbers have summitted Everest without oxygen: by attaining a degree of acclimatisation, they have been able to achieve this. A similar analogy could be drawn with flying in from Chengdu, which is barely above sea level, to Lhasa, at 3,650m. That’s a 3,500m gain in an hour or so. You need to rest and recover.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on ISTM. For other journey preparation information, consult NaTHNac (UK) or CDC (US). Information about various medications may be found on NetDoctor. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

As with any Third World travel situation, you need to keep your wits about you in Tibet. Theft of luggage is uncommon on the plateau, but it does happen. Ditto with rented bicycles – lock yours in a secure, highly visible location. Luggage has even gone missing from some budget hotel storage rooms in Lhasa; to reduce the risk of this happening, identify your baggage with your passport number prominently displayed on an attached label. Keep an eye on your bags when on the move. Pilfering of personal items is known to be a risk when trekking in some areas, particularly the Everest region.

Because of the heavy Chinese military presence in Tibet, armed robbery or similar crimes are extremely rare, though in old Tibet banditry certainly existed in more remote areas. A greater threat to life and limb is on 4×4 sorties and through resulting confrontations that may develop on these trips. Apart from the major health hazard it presents, high altitude is known to befuddle the brain, making you irritable and unable to focus when making decisions or when judgement is required. And there are important decisions that need to be made: for example, to size up quickly those on whom your life depends. That means that, if a rental vehicle or taxi driver refuses to slow down and keeps overtaking recklessly, you may have to bail out.

Confrontations between drivers, guides and passengers over changes of itinerary or other problems can turn ugly. Incidents have involved both Tibetan and Chinese driving crews. In the Everest region, when a driver and his guide (both Tibetan) refused to drive beyond Rongbuk Gompa for the extra dozen kilometres to Everest base camp, a passenger swore at the guide. The guide picked up a rock and hurled it at the passenger. The rock missed, but the passenger was in a state of shock that he would even attempt such a thing. Disagreements between passengers themselves can also turn nasty. Other arguments may erupt over permits and permission with Chinese authorities, who are not noted for their politeness. In all of these situations, mediation skills are called for: stay cool, be patient, be polite yet insistent, and keep your temper to yourself.

Female travellers

Although Tibetan Buddhism promotes a code of respect, there have been cases of harassment of Western women by Tibetan men, especially on crowded buses and when hitching rides in trucks. Tibetan women dress modestly, with little flesh exposed, and that may be the key here: a Western woman wearing shorts and a revealing top may send out the wrong message, and is bound to attract the wrong kind of attention. For these reasons, travelling solo in Tibet is not advisable for a woman. However, a woman who speaks enough Tibetan – and who dresses modestly – should not have a problem. Chinese men and Chinese military appear to have little interest in sexual advances to Western women, perhaps due to the phenomenon of numerous Chinese prostitutes plying their trade at karaoke bars in the larger towns of Tibet.

Travelling with a disability

Until the 1990s, there was only one elevator in the whole of Tibet, at what was then known as the Holiday Inn in Lhasa. Tibetans used to sneak into the hotel to experience this wonder of the Western world. That will give some idea of the problems facing disabled travellers: Tibet can be a very rough ride. If hotels lack elevators, think about monasteries – none of them have anything remotely resembling an elevator. And monasteries and fortresses are often built on hilltops, with steep access.

Still, if a blind climber can overcome the obstacles and make it to the top of Everest, then nothing is impossible. Erik Weihenmayer made it to the summit in 2001 from the Nepalese side. In 2004, he came to Tibet to visit his friends Sabriye Tenberken and Paul Kronenberg, the co-founders of Braille Without Borders, a project in Lhasa to help blind Tibetans. Erik inspired blind teenagers at this school to climb on Rongbuk Glacier at the north side of Everest. A documentary called Blindsight was released in 2006, describing these encounters. The best advice for disabled travellers is to ensure that you are going with a travel agent knowledgeable about potential problems and hazards, and who can provide the logistical support and help needed. Navyo Nepal is a Kathmandu-based operator with experience in organising tours for disabled travellers in Nepal and Tibet.

Travelling with children

Tibet presents challenges for travel with young children, as the dryness and altitude can make them irritable. Then again, as so few foreigners come to Tibet with children, this is of great fascination to local Tibetans, who fawn over the kids. Be aware that medical facilities are sub-standard in Tibet, so you will need to second-guess on the medical front and arrive well prepared for any contingencies. It’s hard to say what would make Tibet entertaining for kids. Monasteries, probably not. But kids love yaks – they are new creatures to marvel at. Going to see the yak dance at a place like Shangri-La Bar in Lhasa will be a definite hit.

To set up connections with Tibetan culture, buy some picture books for kids. Available in Delhi or Kathmandu is a ten-page book titled I am a Yak, which introduces nomad culture. Others in this series published in India include How the Yak got his Long Hair, A Snowlion’s Lesson and The Three Silver Coins. In the West, Tibetan folklore and Buddhist animal tales are available in books for young readers. And the classic story about the yeti is found in Herge’s comic book, Tintin in Tibet.

LGBTQ+ travellers

There are no particular taboos or caveats for gay and lesbian travellers visiting Tibetan regions. Buddhism is an easy-going religion, and highly tolerant. In a country (China) where men (or women) often stroll hand in hand as a show of friendship, gay travellers should not raise any eyebrows. Some tour agents market gay and lesbian tours to Tibet, or have done so in the past. These include Out Adventures and Hanns Ebensten Travel.

Travel and visas in Tibet

Visas

This may sound odd, but the best place to get a long Chinese visa is within China – in Hong Kong. Hong Kong, since the handover, operates as a Special Administrative Region (SAR), with the Chinese Embassy simply altering its name to PRC Visa Issuing Office. The office is located in the China Resources Building in Wanchai – you can approach this office yourself, but travellers usually go through agents for convenience. In short order, in Hong Kong, you can pick up a one-month visa (can be processed next day, HK$350/US$45). Multiple-entry visas are possible, valid for one month each entry. Some travellers, especially Americans, may only be granted a one-month visa. A three-month visa for HK$350/US$45 was previously available but now seems elusive. The Chinese Embassy insists on receiving passport photos taken with a light blue background: the travel agency can arrange this.

There are certain things with which you should be careful when applying for a visa. Do not mention Tibet or Xinjiang as destinations. Travellers have had their visa application knocked back solely for doing this, and been told they need special permission to travel to those places. Safer destinations to mention are Beijing and Shanghai. Reason for visit: tourism. Your job: do not put reporter, journalist, writer, photographer, missionary, diplomat or politician, as your visa will not be processed. These people require special permission to travel in places like Tibet – this involves a complex procedure that may not succeed. Travel agents in Hong Kong will advise you how to fill in the application.

Visas have a coding on them: the L visa (luyo) designates a regular tourist; the F visa (fangwen) is a longer ‘business’ visa, also issued to cultural exchange students – this visa can raise eyebrows if you stray into Tibet; the Z visa is issued to those working in China. A visa issued in Hong Kong may start running immediately (from the date of issue), which means you’ll lose a week or so just getting to Tibet. Visas from other embassies usually start from the date of entry into China, and will give you a two- or three-month leeway to get there.

According to the Chinese, Tibet is an integral part of China. When you apply for the visa, however, do not mention you want to go to Tibet. While a Chinese visa is good for Tibet, authorities there may not extend your initial visa in Lhasa without fulfilling demands like joining a tour. Therefore get the longest visa you can – two months, three months – at the point of origin. Not all Chinese embassies abroad are created equal. Some will grant you three months, others two months maximum, and still others only one month.

Embassies closer to China are the most liberal in issuing longer visas, it seems. Hong Kong is good (three-month visa or longer is possible); Hanoi is not bad (two months possible); Islamabad offers a two-month visa; the Delhi embassy may provide a two-month visa if prodded (but otherwise will only issue one month); the Bangkok embassy normally issues visas of only one month. You might try your home country to see if you can wangle a three-month visa. Explain that China is a big place and you need a long time to see it all. Visa extensions are dodgy within Tibet, but may be possible in big cities in China.

Applying for a Chinese visa in Kathmandu is troublesome, because the Chinese Embassy there is in the habit of only issuing visas for the length of a tour to Tibet booked through an agent in Kathmandu. You cannot apply to the embassy as an individual: you can only approach them through a travel agent. If you already have a Chinese visa issued elsewhere and apply for a short Tibet tour in Kathmandu, the embassy in Kathmandu is likely to cancel it and reissue another visa valid for the length of the tour. If you do not want this to happen, argue the case that you want to fly on from Lhasa to Beijing after their tour and need the extra visa time.

Getting there and away

Getting into Tibet is a two-, three- or four-part operation. First you need to cue up arrangements well in advance with an agent for the TAR itinerary. Then you have to make it to a staging-point such as Bangkok, Hong Kong, Kathmandu or Chengdu. Then you wrangle with more paperwork and ticketing, run the gauntlet of Chinese officialdom into China, and strike for Lhasa. Think of this exercise as ‘hitting the roof ’ – an oblique reference to the way you will feel when you deal with Chinese officials. It’s also what will probably happen to you when you ride in a rental vehicle in Tibet.

Route strategies

Direction of travel becomes very important in Tibet. Getting in from Kathmandu to Lhasa is a killer (problems with permits and altitude), but exiting from Lhasa to Kathmandu is a piece of cake. Because Nepal to Tibet is an international arrival, it leads to many more visa and red-tape complications. Travellers obsessed with getting to Tibet go to great lengths: having found their route stymied in Kathmandu, some travellers have flown all the way back to Hong Kong and back to Chengdu, and then back to Lhasa! (There’s also a direct Kathmandu–Chengdu flight, but it is very expensive). If you look at the map, you can see why that rerouting costs a small fortune as opposed to a direct Kathmandu–Lhasa flight. Occasionally Chengdu is blocked too – possibly because of some Chinese official visiting Tibet – and travellers have proceeded all the way up to Golmud by land, and then overland to Lhasa.

More than in most places, you need to think about your route to and from Tibet because of visa complications. There’s only one consulate in Lhasa – the Nepalese (you actually don’t need a Nepalese visa as you can pick it up on arrival). That’s fine, but what about going overland to Kashgar, via Xining, and then exiting on the Karakoram Highway into Pakistan? The nearest place for a Pakistan visa is Beijing. The overland travel situation is much easier in Kunming, which has consulates for Vietnam, Laos, Burma and Thailand. Visa acupuncture points for Asia include Kathmandu, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Hanoi, Singapore, Beijing, Islamabad and Delhi. Some visas are readily available upon arrival by land or air: these include the Nepalese visa, Thai visa, and Hong Kong entry visa.

Getting around

All roads lead to Lhasa. Sooner or later, you will end up there. Getting around the towns in Tibet presents little problem: they are mostly small enough to walk around. Larger cities like Lhasa, Shigatse and Tsedang have public buses plying the streets, and fleets of Volkswagen taxis roving around (you can also hire these by the day or half-day). Another taxi-like option is using the motorised three-wheelers and foot-powered trishaws as transport. Renting a bicycle is another excellent way of getting around, if you can find one (easy in Lhasa). In Shigatse, you can take a walking-tractor – a tractor with handlebars controlling the engine up front, and a carriage at the back – across town for a small tariff.

Permits and prefectures

Within Tibet you are classed as an alien, and you require an Alien Travel Permit (ATP). Various annoying pieces of paper with fancy chops (Chinese signature markers) and seals dog your movements into and around Tibet – this is not like mainland China where you can virtually travel without restriction. Apart from ATPs, other permits are issued: TTB, military, Foreign Affairs, Cultural Bureau permits. Foreigners are usually never shown these documents, nor allowed to keep them – they’re classed as secret. The guide will keep the permits (you could try to get a photocopy). To get an overview of the complicated situation for permits, consult the map (see above) showing prefectures of the TAR with area codes. The TAR is divided into seven prefectures, each with its prefectural capital or seat, and each with its own telephone area code. Permits are normally only issued in the prefectural capital, although permits for any destination can be issued in Lhasa through agents.

By rental vehicle and guide

The Chinese insist that the only way you (as a foreigner) can get around Tibet is in a hired vehicle (usually a Toyota Landcruiser or similar means of transport, such as a Hyundai van, Buick van, Toyota van or Mitsubishi Pajero) with a driver and guide. This works out to about US$230 a day which, split between four paying passengers, is less damaging. Most of the operators are connected to Chinese channels – routes may be monopolised by TTB-connected vehicles. Vehicle hire is the greatest expense you’ll incur in Tibet. Many vehicles operate on the Lhasa to Kyirong run (to the Nepalese border). You can possibly find them in Shigatse (but don’t count on it). Most make use of Lhasa as the home base. One peculiar phenomenon you will have to deal with in Tibet is called ‘hitting the roof ’. This is when the vehicle (which has no seat belts) hits a rut and launches those in the back seat straight into the roof. It hurts! To soften the impact, think about wearing a wool hat or something similar. The idea of padded interiors has not caught on yet.

By taxi

Taxis are intended to be a mode for getting around larger towns like Lhasa, Shigatse or Tsedang. However, they also commute from Gongkar Airport into Lhasa, a distance of around 75km, so think about this: they’re much cheaper than hiring your own transport. Taxis are viable if the road is paved and in good condition: you can also hire a taxi by the half-day or full day and use it as your touring vehicle, which makes sense if three or four travellers get together to share the rental.

On your own

You need considerable stamina, perseverance and devious ingenuity to mount your own trips in Tibet and break away from the vehicle and guide syndrome. In the pre-2008 days of Tibet travel, when permits were lax, travellers hitchhiked on trucks and took local buses, or proceeded on foot. Crazy dreamers have found ingenious ways of getting around inside Tibet. Back in the early days of independent travel in Tibet, in the 1980s, two Americans transported their kayaks up to Lake Manasarovar and started paddling the Yarlung Tsangpo – they made it part of the way. A young Englishman managed to bluff his way through the Nepal–Tibet border with a motorcycle, and he was out by the Great Wall by the time the authorities caught up with him. Others have rented (or bought) yaks or donkeys to carry their gear, and headed off on long hikes, and have indulged in camping and horse racing combination forays.

If you have money coming out your ears, of course, you can arrange to realise any dream you want through official channels. All the paperwork and aggravation might take some of the joy out of it, though. I’ve met several trios of motorcyclists from Europe who’ve been all over Tibet and Xinjiang on their imported bikes. They would not, however, divulge the cost of the entourage of vehicles accompanying them (with national guide, local guide, translators, medic, etc). A high-end hotel in Lhasa quoted a price tag of Y12,000 for each motorcyclist on a five-day sortie to Everest base camp (based on three riders, with BMW 800cc motorcycle supplied).

When to visit Tibet

April to October is the best time. November is starting to get cold. December and January can be freezing, with heavy snow blocking high passes and poor driving conditions. February is Tibetan New Year and though cold it can be lively, if you can get in. April can be windy; there’s a rainy season around July and August, when flooding can cut off roads and wash out bridges. Because Tibet is so large, climate conditions change from east to west and with the elevation. Because of these elements, Tibet is really only open to foreigners for seven months a year, from the start of April to the end of October. Read on to find out why March is likely to be closed.

Climate

The climate of Tibet is cool and dry. With an average elevation of 4,500m, the weather in Tibet can best be described as extreme, oscillating from searing heat to freezing cold – sometimes in the course of a single day. It is possible to be simultaneously hot and cold, if a person’s head is in the shade, but his or her legs are in the sun. Climatic conditions vary with elevation and exposure: there is little moisture in the atmosphere and intense UV rays can be problematic.

There is no best time to visit Tibet: the weather is unpredictable and, no matter which season, there are extreme conditions to deal with. Few travellers visit during the winter, however, because of treacherous road conditions, because access flights often close down for this period, and because Nepali hotel and restaurant managers head back to Kathmandu for the winter season.

Spring

March to May. Strong winds are possible and can whip up dust storms and sandstorms. However, this is one of the better trekking seasons, when conditions are not too hot.

Summer

June to August. In this period are higher temperatures, which are conducive to staging festivals such as horse-racing fairs. Most of Tibet’s rainfall occurs during July and August. In southern and eastern Tibet, the Himalaya form a barrier against the rain-bearing monsoons, so Tibet does not experience heavy monsoons like Nepal, Sikkim or Bhutan. However, in Tibet rainwater build-up combined with glacial meltwater can result in rampaging rivers and flooding in the autumn.

Autumn

September to November. As a result of the aforementioned rampaging rivers, travel in autumn is prone to delays due to mudslides, flooding and bridges that have been swept away. Otherwise, it’s not a bad time to travel, and it can be sunny.

Winter

December to early March. Severely cold conditions and snowfalls can shut down high passes to traffic. The Tibetans call the plateau Kangjong (Land of Snows), but the sun is quick to melt off snowfalls in the central Tibetan region. February and March are good festival months: Losar (Tibetan new year) falls in this period and during this time there are many nomads in Lhasa.

Timing, festivals and sensitive periods

Rules and regulations concerning travel in Tibet change as often as the weather does with El Nino, so the following sections may be out of date by the time you plan your visit. If so, make adjustments. There are several times of year when it is difficult or impossible to get into Lhasa. Winter is an obvious one – there are no flights from Kathmandu and fewer from Chengdu. The Chinese may be nervous if some military bigwig or political leader is visiting, and they might just shut the whole of Tibet down for a few weeks. Nothing is guaranteed in Tibet, and no guidebook written in stone. Allow for changing information.

The Tibetan calendar is filled with unofficial anniversaries, and security is tight at these times, with Chinese troops on alert ten days before and after the sensitive period. You may have trouble getting into Tibet or travelling around at these times. The easiest travel months are April, June and August (however, June to August is the most heavily booked period for flights into Lhasa). Among the ‘hot’ times are:

- Losar Tibetan New Year, around February

- 5 March Commemorating major protests in 1988–89

- 10 March Anniversary of 1959 Lhasa uprising, and marks the start of the Tibetan spring – protests across the entire plateau in 2008

- 14 March Commemorating riots of 2008 uprising

- 23 May Marks the 1951 surrender to the Chinese with the 17-Point Agreement

- 6 July Dalai Lama’s birthday

- 27 September Start of 1987 riots

- 1 October 1987 protest in which Tibetans were shot dead

- 10 December International human-rights day, which sparked a protest in 1988

Tibetans sometimes gather at countryside locations to picnic and throw tsampa in the air to mark special occasions. In Lhasa, this practice has been banned by Chinese authorities.

Because the Chinese are nervous about large gatherings of Tibetans, traditional festivals are low profile – indeed, for a number of years, festivals were banned outright. If you get a chance to see something more formal, like a festival in the countryside, go! If you’re lucky there might be a horse-racing festival in progress at Damxung (Damshung) or Gyantse, or a tanka-unfurling ceremony at one of the monasteries within reach of Lhasa. There used to be festivals at every full moon in Tibet, but many were abolished by the Chinese authorities. The festivals that survive are based on the lunar calendar, which is complex and unpredictable (usually only announced in February, at Losar or Tibetan New Year). Ask around when you arrive in Tibet to confirm if there are likely to be any festivals in progress.

What to see and do in Tibet

Gyantse

Gyantse was established as the personal fiefdom of King Pelden Sangpo, in the 14th century. His successor, Rabten Kunsang Phapa (1389–1442), extended the fiefdom’s range, and constructed Palkor Choide Lamasery and the mighty Kumbum, both of which are still standing today.

Gyantse is sandwiched between a huge fort and a monastery © Steve Allen, Dreamstime

In later centuries, Gyantse developed as an important centre of the wool trade in Tibet, and a bustling caravan stop on the trade route from Lhasa to India. That route – leading to Sikkim and Bhutan – was closed by the Chinese after they took over in 1950. Gyantse has since fallen into obscurity, its role usurped by Lhasa under the Chinese. This situation, however, has left Gyantse intact as a Tibetan architectural entity, which is something quite rare amid all the Chinese destruction and reconstruction. Gyantse has a largely Tibetan population – perhaps around 20,000. There is a huge fort at one end of town, walled-in monastery grounds at the other end, and a ramshackle marketplace with older buildings and alleyways between fort and monastery.

In the late 1940s, Italian photographer Francesco Mele passed through Gyantse. Here’s his description of the market:

Its market is rich, due to the wool trade and the Indian and Chinese imported objects sold there. The shops are near to the main street, and many of them are simply tents. Here women wearing silver and turquoise jewellery sell clothing and household articles … There are even some Nepalese and Bhutanese salesmen, and a few Muslims who have taken the few weeks’ journey from Ladak in order to sell their products in Gyantse. Muslims are often employed as butchers of yak and goat here, since the Buddhist religion forbids Tibetans to kill animals. Fresh and dried beef and mutton hang in every part of the market, giving it an oddly surrealist appearance.

Gyantse market appears to have died: there isn’t a whole lot happening around the old quarter any more. Instead, various smaller street markets are scattered around the town. Nevertheless, Gyantse is a great place to visit, and will give some idea of what an intact Tibetan town must have looked like.

Buildings in Gyantse date back as far as the 14th century. One of these is the massive dzong (fort), occupying a strategic hilltop at the southern end of town. The dzong guarded the road to Lhasa, and the invading British expedition of 1903 found it a formidable obstacle. The British eventually stormed the dzong, the Tibetan defenders capitulated, and there was no further resistance on the road to Lhasa.

Although the last of the British forces withdrew in 1908, several vestiges of British presence remained in Gyantse, in the form of a British Trade Agent, a British wool-agent station, a British post office (with a telegraph line running to India), and later a British-run school for upper-crust Tibetan children. By the 1940s, a great deal of Gyantse’s sheep wool production was slated for export to British India. There was little interest in yak wool, which was too harsh in quality, although in the pre-synthetic era the beards worn by Santa Clauses in US department stores were made from yak-tail hair. Gyantse became a funnel for the export of wool due to its location, and wool was brought here from outlying areas of Tibet.

The 1950s saw a period of severe dislocation in Gyantse. In 1954, the town was nearly destroyed by flooding; in 1959 the local industries were virtually dismantled with the exodus of artisans from Tibet and the removal of others to work camps. After putting down the 1959 revolt, the Chinese imprisoned 400 monks and laymen at the monastery of Gyantse. During the Cultural Revolution, the monastery itself was ransacked and dismantled – items of value were either destroyed or shipped back to China. Gyantse Kumbum, however, was spared. Since 1980, the Chinese have attempted to stimulate the handicraft production for which Gyantse was so famous. But if there has been any stimulation, there is little evidence of it in Gyantse’s present-day marketplace.

In the late 1990s, Chinese authorities embarked on a propaganda blitz in Gyantse, naming it ‘Heroic City’ in praise of valiant Tibetan resistance to British troops in 1904. In Chinese terms, the logic runs thus: ‘Tibetan patriotic soldiers safeguarded state sovereignty and territorial integrity – defending the Tibet–China Motherland.’ These propaganda efforts were most likely tied in with a round of Brit-bashing after the 1997 handover of Hong Kong. First there was the 1997 release of Red River Valley, a Shanghai-made epic movie about the British in Tibet, with on-location filming at Gyantse. This was followed by renaming the main street of Gyantse ‘Hero Street’, and the erection of a huge obelisk as a monument to heroic Tibetan fighters. The monument makes a convenient navigation landmark, right near the town’s central roundabout.

Labrang Monastery

Labrang Monastery was founded in 1709 and rapidly grew to become one of the six great Gelukpa monasteries. The main assembly hall was rebuilt after being destroyed by fire in 1985, but most of the other halls survived the Cultural Revolution relatively intact, and contain beautiful works of art. You will most likely see elaborate yak-butter sculptures. The monks’ quarters have been rebuilt in recent years and some are spacious and comfortable. A 3km kora lined with prayer wheels surrounds the complex and is well worth the walk. The temples and colleges of Labrang can only be visited on a morning or afternoon official tour. Labrang acts as a major teaching centre and monks come from not only the 108 satellite gompas scattered throughout nearby counties, but also from central Tibet and Mongolia. Thus the number of monks is somewhat fluid, although there are likely to be around 2,000 here. There is also a small nunnery and Nyingma temple on the far side of the complex. You can be sure that with such a large contingent of monks, the Chinese keep a close eye on proceedings. Surveillance was stepped up upon the arrival of the Chinese-appointed Panchen Lama to take up residence in 2011 – in an attempt to legitimise his religious role.

The number of monks at Labrang Monastery fluctuates but there are usually around 2,000 © Shizhao CC-BY-SA

At a cool 2,900m, Xiahe makes an excellent base for hiking. Foreigners tend to stay longer than intended at Labrang, not only because of the monastery and Western food, but also because of the opportunity to see the surrounding hills and grasslands. Bikes can be hired to reach the Sangke grasslands region, where picnics are available in Tibetan-style tents, and where horses can be hired. The nearby hills offer good opportunities for day walks, and you may be offered butter tea and yoghurt if you reach the nomad camps higher up, but beware of dogs! The most vicious dogs are chained up, but some of the others do present a serious danger if you enter their territory unbidden. Carry a walking stick, some stones or a gokor (a lump of lead on a string) if you plan to visit these areas. The dogs around the monastery are generally very docile, but still should not be approached.

Lake Basum Tso

About 280km east from Lhasa and 48km east of Kongpo Gyamda is a turn-off northward, leading another 47km on a paved road to Basum Tso (Basong Tso, Draksum Tso; 3,470m). The lake can be reached in 5–6 hours’ drive from Lhasa. From the other direction, the lake is 125km from Bayi.

The green area of Lake Basum Tso has been called Tibet’s ‘Little Switzerland’ © Gao CC-BY

Basum Tso has been granted top-level tourism status by the PRC, meaning it will invariably be flooded with Chinese tourists. This ethereal lake is associated with the legend of King Gesar of Ling, Tibet’s epic poem. You can visit enchanting Tsodzong Gompa, on a tiny island reached by a pontoon walkway. This small gompa was rebuilt by Dudjom Rinpoche, the highest-ranking Nyingmapa lama from the Kongpo area. Dudjom Rinpoche died in exile in 1987. Several nuns look after Tsodzong Gompa. The entrance to the lake is located 4km before the actual lake. From here, you can walk or take a shuttle bus to the lake visitor centre, just before the bridge leading to Tsodzong Gompa.

There is a two-day pilgrim circuit around the lake, but modern pilgrims don’t bother – they just take a speedboat for an hour to reach the sacred spots up one end of the lake. There is a landing spot up the far end where you disembark and walk inland to a waterfall site where pilgrims rub themselves against revered stones and squeeze into impossible cave crevices.

Lake Namtso

Some 40km from Damxung is Lake Namtso, reached by two routes – in a 4×4 you can enter one way (motoring over Largeh La, 5,180m) and leave by another route (over Kong La, 5,150m). At a tollgate near Damxung, a Y120 per person entry charge is levied to enter Namtso Lake Nature Reserve (this tariff drops to Y60 for the November to April period). Driving on the paved road over Largeh La, it takes an hour to reach Lake Namtso: the road runs through a grassland valley, with the odd nomad encampment visible, and herds of yaks, sheep and goats roaming around. For the nomads, life is dependent on yaks: they live in yak-hair tents and use yak dung as their main fuel source. Some travellers trek into Lake Namtso – a tough hike taking 12 hours (one-way).

At 1,920km2 in surface area, the salt lake of Namtso is the largest lake in Tibet © Peter Stein, Shutterstock

Overnighting at Tashi Dor is recommended because bus tours from Lhasa can overwhelm the area during the day: if you stay overnight, it’s more tranquil when you take in sunset and sunrise. There are several possibilities for basic lodging at Namtso. The area close to Tashi Dor is crowded with tent guesthouses and metal or thin wooden shacks, each charging about Y50 a bed. Some group tours bring their own tents and camp out. Further back from the lake is a more permanent structure where guests can stay. There are some teahouse-type restaurants operating out of tents, selling soup or noodles. Bring extra food, a flashlight and a good sleeping bag if you can – nights are freezing. There is private generator lighting and electrical supply for a few hours at night.

Namtso is a sacred lake: there are cave-temples, shrines, hermitages and a nunnery for contemplation at Tashi Dor. That is, assuming you can get away from the annoying vendors of cheap jewellery and other shoddy wares, and those intent on talking you into posing with various animals for photos (for which you pay, of course). Two large rock towers near the nunnery are considered to be sentinels for the region. It’s worth spending a day or more exploring the area, hiking in the hills around Tashi Dor, and poking around the cave-temples. Hermits from the Kagyu and Nyingma sects occasionally occupy the caves in the area. The beautiful turquoise hues of the lake are a source of inspiration, and the vistas will redefine your sense of space. In the distance, to the south, the 7,088m snow cap of Mount Nyenchen Tanglha looms up, along with the range of the same name. A walking circuit of Namtso is a tall order indeed. The lake is roughly 70km long and 30km wide, with a surface area of 1,940km2: it takes nomad pilgrims up to 20 days to circle it. A short walk to the east of Tashi Dor is a site that operates as a bird sanctuary –between April and November there are good chances of sighting migratory flocks, including, if you’re lucky, the black-necked crane.

Litang/Tagong grasslands

Litang is a town with a dusty high street lined with bland Chinese shops and small businesses. It is best used as a launching pad to visit the nearby grasslands and see nomad herders. Club together with other travellers and rent a minivan for the day for Y500 or so.

Litang’s claim to fame is the annual horse-racing festival, which takes place on nearby grasslands in the first week of August. It was started up by Chinese officials to boost tourism, with fixed dates from 1 to 7 August. On 1 August 2007, a nomad called Rungye Adak snatched the microphone at centre stage and delivered a short speech about nomad grazing problems, about freedom of religion, and about the return of the Dalai Lama. He was promptly arrested and sentenced to eight years in jail. The festival was suspended for ten years but resumed in August 2017. This is the biggest horseracing festival in the region; there may be other smaller festivals in nearby grasslands.

The Litang area is characterised by beautiful grasslands © Pablomielniezuk CC-BY-SA

Around the town, Litang Gompa is worth the visit. Litang was a hotbed of resistance to Chinese rule, and the monastery was bombed and strafed by Chinese planes in 1956. It has since been rebuilt and is fairly active. On the outskirts of town at a hilly spot is a sky burial site. Some hotels drive guests over to witness the ceremony (assuming there is a body that day), charging Y100 for each tourist. This macabre form of profit-making needs to be discouraged out of respect for the Tibetans. You can hike to the spot yourself, or can arrange to have your driver get there in the morning before going out on a day trip to the grasslands. Do not attempt to take photographs at the sky burial site.

Going from Litang to Tagong, you’re on Highway G318, the southern and most-used overland route between Chengdu and Lhasa. Numerous high passes and steep drops into valley bottoms make this a very challenging highway no matter which direction you head from Litang. Some 18km east out of Litang you have the option of a shortcut north via Xinlong to Ganzi in the northwest corner of Sichuan. The main highway east twists up into high country, culminating in a 4,487m pass before a wild descent into a forested valley and the city of Yajiang on the Yalong River, a major tributary of the Yangtse. A climb over a 4,475m pass brings you to a highway junction in a wide valley just before Xinduqiao, a trading town. The northern branch of the Sichuan–Tibet Highway branches off here; turn on to it for Tagong, just a short 33km jaunt north up the valley, which narrows to a little gorge before opening on to the Tagong Grasslands.

The gorgeous setting at 3,750m and a handful of Westerner-friendly guesthouses and restaurants have made Tagong a traveller’s centre, though it’s small scale. The temple is well worth a visit with three main chapels full of Tibetan artwork, a chorten field behind, and a kora lined with prayer wheels. The Tagong area has many good walks among the high, grassy hills to temples, a stupa and viewpoints. If your timing is right (end of summer on lunar calendar) you might catch the annual horse-racing festival of Tagong, which is staged on grasslands about 40 minutes’ drive away. And that could be also the time that the annual Cham dancing is staged in the courtyard of the beautiful temple at the centre of Tagong.

Mount Kailash Kora

The circuit around the sacred mountain is known as the Kailash kora. Tibetans complete the circuit in one long day, starting before dawn and finishing after nightfall. Unless you are super-humanoid, don’t attempt this at altitude. The minimum time for most Westerners to complete the circuit would be two days. Most allow three to four days. If you have a tent and want to dawdle, taking in the landscape at a leisurely pace, plan on five days or more. An annoying Y180 fee is levied for the Kailash kora for each trekker. There is a checkpoint about 250m past Darchen to check your ticket – if you don’t have a ticket, you can buy one there. Porters for the trek can be arranged through a government office for about Y260 a day, or Y780 for the three-day trek. Trekkers should tip the porter at least Y100 at the conclusion of the trek.

What price for accumulating merit? There are rumours of a fast track for doing this: there is ominous talk of the Chinese building a motor road around Kailash, presumably with a toll gate.

Mount Kailash is a 6,638m peak in western Tibet © Zzvet, Shutterstock

In group-tour arrangements, porters or yaks (or both) are deployed to carry camping gear and guest duffle bags. The group tours sleep in tents close to monastery guesthouses. Previously, individuals could stay in the monastery guesthouses on the kora, but that option seems to have closed down. Don’t expect much in the way of food on the circuit, although there may be some teahouse tents along the way. Sometimes the gompa guesthouses sell noodles. A clean water supply is essential, so take water bottles and filtering devices (water can also be boiled).

Fellow hikers at Kailash are mainly Indian and Tibetan pilgrims. The Tibetans come from as far away as Kham, usually arriving by ‘pilgrim truck’. Tibetan pilgrims comprise many different nomad groups with a fascinating array of costumes, particularly the women. Women coat their faces in tocha – a cosmetic made of concentrated buttermilk or roots – to protect the skin from dryness and UV rays. Indian pilgrims come as part of a lottery system run by the Delhi government, in operation since the early 1980s. Each year, up to 10,000 Hindus from all parts of India apply. Finalists are chosen and, after fitness tests, this number is whittled down to about a thousand. Hindu pilgrims are allowed ten days in Tibet. Travelling in groups of around 35, the lucky lottery winners walk across Lipu Lek pass where they are met by Chinese guides and the sacred circuit of their dreams gets under way. However, these lottery pilgrims are dwarfed in number by those wealthier Indian pilgrims who reach Kailash as part of 4×4 convoys.

Potala & Jokhang

The Lhasa area is home to not one but two UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the temple of Jokhang and the palace of Potala.

The Jokhang

The Jokhang or Tsug Lakhang (central cathedral) is Tibet’s most sacred temple – the heart of Tibet – with streams of pilgrims coursing through. The temple was built in the 7th century by King Songtsen Gampo when he moved his capital to Lhasa. Apart from his three Tibetan wives, the powerful Songtsen Gampo had two wives offered by neighbouring nations – Nepalese queen Tritsun and Chinese Princess Wencheng. The Jokhang was originally designed by Nepalese craftsmen to house a Buddha image brought by the Nepalese queen. Upon Songtsen Gampo’s death, Princess Wencheng switched the statue she had brought (the Jowo Sakyamuni) from the Ramoche Temple to the Jokhang, apparently to hide it from Chinese troops. That’s why one part of the Jokhang (Chapel 13) is called the ‘Chapel where the Jowo was hidden’. In time, the Jowo Sakyamuni statue became the chief object of veneration. The Jokhang was enlarged and embellished by subsequent rulers and Dalai Lamas. Although the building is as old as Lhasa, much of the statuary is quite new. During the Cultural Revolution, the temple was used as a military barracks and a slaughterhouse; later it was used as a hotel for Chinese officials. Much of the statuary was lost, destroyed or damaged, so it has been replaced with newer copies of the originals.

Jokhang Temple was built for the two brides of King Songtsen Gampo © Antony007007, Dreamstime

In 2000, the Jokhang was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list as an addition to the Potala Palace (below). Initially, this was greeted as good news, as it implied protection of the buildings in the immediate vicinity. However, ancient buildings around the Barkor have since been knocked down and replaced with Chinese copies, on the dubious grounds of superior plumbing and facilities. Then in early 2018, disaster struck: on the second day of Losar, a huge fire broke out in the rooftop area of the Jokhang, causing considerable damage from fire and water.

Potala Palace

The Potala was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1994. The citation says: ‘The Potala, winter palace of the Dalai Lama since the 7th century ad, symbolises Tibetan Buddhism and its central role in the traditional administration of Tibet.’ Chinese authorities conducted a five-year multimilliondollar restoration of the Potala, completing work in 1995. Why restore a palace that is the former abode of Public Enemy Number One? Because it’s a major tourist attraction, of course – and one that generates millions of dollars in income annually. Unlike the Jokhang or the monasteries around Lhasa, the Potala is run by Chinese tourist authorities: the practice of Buddhism is essentially banned in the palace.

Potala Palace is a popular destination for pilgrims © Hung Chung Chih, Shutterstock

Once humming with spiritual activity, the Potala is now a lifeless museum, a haunted castle. A lot of the Chinese restoration was directed at the enclosing walls, which were damaged by Chinese shelling during the 1959 uprising. Adding considerably to the bill is the ‘wiring’ of the Potala. Electrical hook-ups have been enhanced and video surveillance cameras have been installed throughout. The cameras are to monitor the 60-odd caretakers at the Potala, who pad around in purple trench coats. On a more practical note, fire extinguishers and other devices have been installed (following a disastrous fire that broke out in 1984 due to a short circuit).

Below the Potala, within the enclosing walls, used to lie the Tibetan administrative quarter of Shol. Some buildings in this zone have been destroyed. One building has been turned into a hotel; the others are used as art galleries, souvenir shops, or occupied as residences. Before 1950, Shol quartered the offices of the Tibetan government, Tibetan Army officials, guard offices and a prison. Other sections of the Potala were used to house Namgyal Monastery, as well as a community of monks and a school for monk officials.

Samye Temple Complex

Samye is thought to be Tibet’s first monastery and its first university. It has been deconstructed and reconstructed a number of times. The monastery is thought to have been founded in the 8th century by King Trisong Detsen, in consultation with Indian sage Padmasambhava. The temple was destroyed during civil war in the 11th century, by fire in the 11th and 17th centuries, by earthquake in the 18th century, and by Mao Zedong’s fanatical hordes in the 20th century. Today, only a fraction of its original 108 buildings survive or have been reconstructed. Adaptations for visitors within the walls include the monastery guesthouse with restaurant and monastery shop. Most Samye villagers live outside the walls.

Samye Temple is thought to have been founded in the 8th century © Tsui CC-BY-SA

Samye’s layout is based on Buddhist cosmology: it is a mandalic 3D replica of the Tibetan Buddhist universe. The temple complex has been constructed according to the principles of geomancy, a concept derived from India. At the centre of the Tibetan Buddhist universe lies a mythical palace on top of Mount Meru, which at Samye is symbolised by the main temple (Utse). Surrounding this is a great ‘ocean’, with four great island-continents, and eight subcontinents. If the colour-coded chortens look a bit out of place in this scheme of things; it’s because they were razed during the Cultural Revolution, and were only reconstructed in the early 1990s, in new brick, with synthetic paints, and without much finesse. Renovation and reconstruction of other parts within the walls is ongoing.

The complex is bounded by an oval wall (the original wall was a zigzag design), pierced by four gates and topped by 1,008 small chortens that represent Chakravala, a ring of mountains that surrounds the universe. The wall itself has been hastily restored, using a large amount of concrete – the favourite material of the Chinese.

There are currently about a hundred monks attached to the main temple. The monastery was built long before the rise of the different sects in Tibet. In the late 8th century, Trisong Detsen presided over a debate at Samye between Indian Buddhists and Chinese Zen Buddhists concerning which type of Buddhism should prevail in Tibet. The Indians won. Since that time, the monastery has come under the influence of various sects, such as the Nyingma, Sakya and Geluk traditions. Even today, influences are eclectic.

Tashilhunpo Monastery

The Tashilhunpo is the seat of the Panchen Lama, a topic that raises blood pressures on all sides. The monastery is highly sensitive because of the controversy surrounding the 11th Panchen Lama. Pictures of the Chinese-appointed 11th Panchen Lama abound as icons at the monastery, but that’s about all you’ll see of him – he is sequestered in Beijing, supposedly for reasons of education. However, in 2016, he was conscripted to conduct a Kalachakra Empowerment in Shigatse – a ritual that is more often associated with the Dalai Lama. Obviously, Beijing is trying to boost the profile of China’s chosen Panchen Lama. The Dalai Lama’s choice of Panchen Lama has been missing in action since 1995, along with his entire family.

Tashilhunpo Monastery, the traditional seat of successive Panchen Lamas, draws many pilgrims © Antoine Taveneaux CC-BY-SA

There are monk-stooges hanging about: take care what you do or say here. Tashilhunpo is immense, a monastic city with temples, assembly halls, living quarters and administrative offices. At its height, it housed up to 5,000 monks. Today, the figure is probably closer to 700.

Tsaparang

Located 26km west of Zanda (a 1-hour drive) are the extensive ruins of Tsaparang, the once-powerful capital of the 10th-century Guge Kingdom. The main building material is not stone, but clay, with walls, buildings, secret tunnels and escape exits all fashioned from this material. Thousands of people lived here in cave dwellings in this kingdom of clay, which appears to have been operational in the 10th and 11th centuries. Little is known of the history of the Guge Kingdom, but some of the exceptional murals at Tsaparang portray realistic scenes with courtiers and visiting dignitaries, and give some idea of how people lived.

Tsaparang is built tier on tier up a clay ridge © Udompeter, Shutterstock

To access temples at Tsaparang, you need the caretaker to open the doors, and you need to pay an entry fee of Y110. The Tibetan caretaker lives in a small house near the main gate: if he’s not at home, he’s probably in the tiny village visible not far away from the ruins. The caretaker may want to see your paperwork, and may insist that no photographs be taken inside the temple structures. Interior photography of the site is a very sensitive point; official permits for photography are complex to obtain (from Beijing), and expensive if you do manage to get them.

Tsaparang is built tier on tier up a clay ridge. The best-preserved parts are the lower ramparts; at the very top are excellent views of the area from the dzong. As you go through the gate into Tsaparang, the first thing you see is the Rust-coloured Chapel, thus designated because its function is not clear – it bears murals of Tsongkhapa, Sakyamuni and Atisha. The White Temple suffered extensive damage to its statuary, but its murals remain intact. Some murals portray Avalokitesvara, the 11-headed, thousand-armed bodhisattva of compassion. The mural style is Kashmiri. The Red Temple was destroyed and left open to water damage, but even so, its murals are striking, with beautiful large Tara frescoes. There are engrossing murals here, apparently depicting scenes from daily life at Guge – in one section envoys are arriving by donkey at the court; another part shows a high lama giving teachings. The Yamantaka Chapel is dedicated to its resident tantric deity Dorje Jigje: the walls bear murals of deities locked in tantric yabyum embraces with their consorts.

From here, wend your way up clay steps, passing through a fantastic winding tunnel to the uppermost ruins. There’s an entire ruined citadel at the top. Once past the tunnel, there is a complex of chambers and passageways: the citadel had its own water supply in times of siege, and the king had an escape route tunnel that led off the rear of the ridge.

At the top, the most impressive structure is Tsaparang Dzong – the king’s simple summer palace – with expansive views over the valley. There are several temple complexes at the top: the most important is the tiny Demchok Mandala Chapel. This chapel is usually locked – if you manage to get in, you can view the remains of a large 3D mandala, which was smashed in the Cultural Revolution. The chapel is a gonkhang (protector temple), and the site of initiation rites. It is thought that in times of crisis, the king and ministers would come to this chapel to ask for protection or direction. The chapel is dedicated to the protector deity Demchok, who is depicted in murals with his consort Dorje Phagmo. Fascinating tantric murals cover the walls: a flashlight is needed to view them. Depicted are rows of dancing dakinis, the female deities who personify the wisdom of enlightenment; below these are gory scenes of disembodiment from hell realms.

Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon

In 1924, two British expeditions crossed paths in Lhasa. One was the ill-fated Everest expedition, heading west with the objective of summitting the mighty peak. The second expedition was heading in the opposite direction, east to the Yarlung Tsangpo Gorge, as it was then known. The expedition was led by botanist Frank Kingdon-Ward, with the eccentric Lord Cawdor in tow to provide financial backing. The object was to collect new plant species, and to hunt for a colossal waterfall, rumoured to be 30m tall.

Kingdon-Ward’s expedition found waterfalls, but not a colossal one. He collected a staggering amount of flora – some 250 species, including the fabled blue poppy. And he overlooked a terrific discovery right under his nose. He was exploring in a canyon more than double the depth of Arizona’s Grand Canyon, deeper than the Rio Colca in the Peruvian Andes, deeper than the Kali Gandaki in Nepal. The definitive discovery that the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon is the deepest in the world was not announced until the mid-1990s. The colossal 30m waterfall that Kingdon-Ward was hunting was not definitively identified until 1998.

Only now is the canyon starting to be launched as a world-class attraction – surely the eighth wonder of the natural world. The problem, as in Kingdon-Ward’s day, is remote and inaccessible terrain. The canyon contains many rare species of flora and fauna, but trails through its wooded slopes are few and overgrown. The weather can be wet (very wet), foggy and unpredictable – the canyon hosts its own unique microclimates. And for foreigners, there’s another great obstacle: Chinese officialdom. The main access point is close to Linzhi, which lies near to a heavy military traffic zone.

Hopefully, this situation will change and this remarkable canyon will be easier to access for foreign hikers and even foreign rafters (closed to non-Chinese travellers). Chinese tourists are able to reach the area. They start out on a day’s drive from Nyingtri Airport, followed by an arduous two-day hike to Zhacu village. Close to this spot, there’s a vantage point with stunning views over a bend in the river, where the mighty Yarlung Tsangpo wraps around the base of Mount Namche Barwa.

An addition at this site is the Namche Barwa Visitor Centre, designed by avantgarde Beijing architect Zhang Ke. The centre houses an exhibition on the history of the canyon, a contemplation space and hiker facilities (including a medical clinic for those struggling with altitude). Down by the river is another facility, a small boat terminal where trips can be taken in direction of Namche Barwa.

You would think that a major attraction like the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon should be preserved in pristine shape, with revenue derived from tourism. Sadly, that is not the case. Chinese officials have chosen a path of exploitation of resources, in a way that will be highly destructive. The Yarlung Tsangpo is slated to be extensively dammed in the coming years.

It is not only the world’s highest river with the world’s deepest gorge; it has far and away the world’s greatest hydro potential, at the Great Bend of the Tsangpo. A proposal made by Chinese engineering consortiums calls for construction of Motuo Dam at the Great Bend, with a staggering output of 38,000MW. That would be far greater than the output of the Three Gorges Dam – currently the world’s largest.

In 2013, a 3km tunnel was blasted through to the remote village of Motuo, with a sealed road. Motuo, also known as Metok and Medog, is a site sacred to Tibetans as one of the ‘hidden valleys’. But now hidden no more. The road boring through mountains to reach Motuo can only mean one thing: a mega-dam is on the drawing board.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Tibet:

Related articles

Tibet is a land of extremes, embracing the wildest rivers, the deepest gorges and the highest peaks on earth.

Tibet’s extraordinary and remote natural landscape includes the world’s highest peak and the world’s deepest gorges.

There’s no better place to meet genuine Tibetan locals than at the region’s sacred sites.