Queen Square, The Circus & the Royal Crescent

Number 1 Royal Crescent

Royal Victoria Park & the Botanic Gardens

Jane Austen Centre

The Assembly Rooms & Fashion Museum

Museums of Bath

Walcot Street & London Street

No area of Bath was left untouched by the architect’s pen when the city was remodelled: even the older streets close to Bath Abbey were tinkered with. But it is as the city moves north, away from the river, that we see the most profound effects. To appreciate the Bath that we see today is to understand something of 18th-century town planning when the city was transformed beyond recognition, and also of the four men who were largely responsible for the changes: Ralph Allen (the man with the money), John Wood the Elder and his son John Wood the Younger (the architects), and ‘Beau’ Nash (the dandy).

Queen Square, The Circus & the Royal Crescent

The builder effectively sold the façades and owners would then create a house behind so that, while there is elegant uniformity from the front, the rear of the property is a mix of rooflines and styles.

These three addresses, some of the most fashionable in Bath, are linked by their architects, John Wood the Elder and Younger. The first to be built, in 1730, was Queen Square, an area of Bath that was badly damaged during World War II in the Baedeker Blitz, when the Luftwaffe targeted places of cultural interest by picking them out from Baedeker guidebooks. On the west side of Queen Square is the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution. The cultural centre provides a focal point for talks, discussions and debates, plus exhibitions throughout the year; you do not need to be a member to join events. A list of forthcoming activities, many presented by eminent speakers and lecturers, is shown on the BRLSI website and in the foyer.

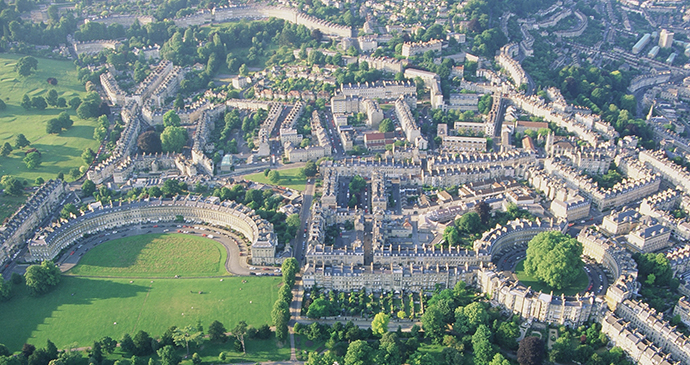

Just north of Queen Square, at the top of Gay Street, is The Circus. Begun in 1754 by John Wood the Elder, it was the first circular terrace in modern Europe but Wood died soon after the first stone was laid and his son (the Younger) completed the project. The terrace was originally called King’s Circus after King Bladud and the acorns that adorn the tops of the buildings are a reference to the king and his swine herd. Wander along Gravel Walk, between Gay Street and Royal Avenue, and you’ll see the interesting backs of the properties that introspectively look to The Circus. The backs seem to reveal so much more and are by no means as elegant as the façades. Accessed through a tiny, half-hidden doorway off Gravel Walk is a Georgian Garden, recreated following excavations that revealed three garden plans. Formal box hedges, bulbs, roses, herbs and hardy perennials all historically correct fill this secretive, little-frequented space with colour.

To the west of The Circus, connected by Brock Street, is the Royal Crescent, designed by both John Wood the Elder and his son, the latter building the famous street between 1767 and 1775. Like The Circus, its shape was a first in modern European architecture. The builder effectively sold the façades and owners would then create a house behind so that, while there is elegant uniformity from the front, the rear of the property is a mix of rooflines and styles.

Number 1 Royal Crescent

Take the opportunity to look out of the upstairs window and imagine the views, without buildings, all the way down to the river.

Despite its grandeur, by the 1960s the Royal Crescent was not a pleasant place to live, having fallen into disrepair (some houses were destroyed in the Baedeker Blitz) and disrepute. Number 1, the first property to have been built in the Royal Crescent with, in theory, the best address of the ‘street’, was one such house. Bernard Cayzer, a man passionate about interior design and the Georgian period, bought the place (for £11,000!) having spotted an advertisement in Country Life. He gave the property to the Bath Preservation Trust together with the funds to refurbish it.

Number 1 Royal Crescent was restored as a museum to show what a grand 18th-century house would have been like to live in. Obviously none of the furniture is original to the house, but each room provides detailed examples of Georgian interior design, with authentic furnishings. Rooms are laid out like stage sets, ready for the men to return to their game of cards, while the drawing room is prepared for visitors calling to take tea. Plastic fruit on the table in the dining room perhaps detracts from the elegance but take the opportunity to look out of the upstairs window and imagine the views, without buildings, all the way down to the river, as in the painting by Joseph Farringdon in the Victoria Art Gallery.

Royal Victoria Park & the Botanic Gardens

A park of many parts, it extends over 57 acres; the Royal Crescent overlooks the section closest to the city centre.

You’d think, by its very name, that Bath’s largest green space is Victorian. To some extent it is, but it was created during the Regency period and named the Royal Victoria Park by a perhaps rather bumptious Princess Victoria when in 1830, at the age of 11, she opened the new park. A park of many parts, it extends over 57 acres; the Royal Crescent overlooks the section closest to the city centre. From there it spreads out north and west to incorporate large greens, filled with numerous specimen trees for summer shelter, formal flower borders in town park style, a vast playground, a duck pond, two golf courses and Botanic Gardens.

In the northwest corner, the Botanic Gardens are the furthest to reach from the city centre, but are my pick of the green spaces in Bath, with lots of distinct areas to give colour throughout the year. Winding pathways draw you from one to another, a rose walk to a magnolia lawn, heather borders to a butterfly garden. Pockets of lawn offer restful places to sit and enjoy the surrounding scents. The main entrance is off Royal Avenue, which curves around the floral part of the garden.

To the north, on the opposite side of the road, is the Great Dell, an undulating tree garden, where the heady scent of pine rises above you and cyclamen sprout at the roots of trees. It’s a restful place, and a world apart from the crowds that gather in front of the Royal Crescent, just ten minutes’ walk away. Gravel paths criss-cross the vast lawns of the park for winter promenading but they are also the launch site for hot air balloons that drift off early morning and evening to give passengers a stunning view of Bath from above. Bath Balloons take off from the Royal Victoria Park three to four times per week; bookings are essential.

Jane Austen Centre

No author is more closely associated with Bath than Jane Austen.

No author is more closely associated with Bath than Jane Austen. The city had been rejuvenated by the time she was alive, the new architecture in place, with balls and concerts in full swing. Indeed, the author was one of the very people who met society in the streets and halls of Bath, observing every mannerism before writing it down.

The Jane Austen Centre is located in a Georgian town house in the same street and just a few doors down from where Jane lived for a while. You can get a sense of Georgian living here (although in this respect it doesn’t quite match up to Number 1 Royal Crescent), but the exhibition brings Jane’s story, and how Bath fits into it, to life. Every visit begins with a live introductory talk, provided at certain times of the day. Occasional temporary displays of reproduction costumes, used for television and film adaptations of Jane Austen’s novels, may be on show but be aware that the exhibition is otherwise little more than a collection of information boards giving details of her life in Bath, presented alongside the occasional replica artefact. While there’s plenty to read, the centre can therefore be a little disappointing if you’re expecting something more. On the second floor are the Regency Tea Rooms, where you can take ‘Tea with Mr Darcy’, served by waiting staff in Regency attire.

Don’t miss the enthusiastically received annual Jane Austen Festival when, for nine days every September, Georgian Bath comes alive with Empire line dresses, ribboned bonnets, gloves and lace parasols as perfectly ordinary people dress up to celebrate everything Austen. Numerous festivities take place, with Regency dances, costumed walking tours, talks, Regency meals and workshops.

The Assembly Rooms & Fashion Museum

Visitors, both children and adults, may try on corsets and crinoline petticoats.

During the 18th century there were two sets of Assembly Rooms. The original rooms, built in 1708 at the request of Beau Nash, were close to the river. When a new set of assembly rooms was built in 1771 close to The Circus, the two were distinguished simply as the lower or upper rooms. The lower rooms burned to the ground in 1820 and all that remains of them, the grand columns from one façade beneath Pierrepont Street, can be seen from the Parade Gardens. So it is the more recent, upper rooms near The Circus that we now know simply as the Assembly Rooms.

Owned today by the National Trust, the Assembly Rooms were once the hub of Georgian and Regency social life, where dances took place, gamblers lost fortunes, matches were made and new husbands found. The grandeur of the rooms – many visit simply to look at the size and beauty of the nine glass chandeliers that hang from the ceilings – remains today. But don’t count on being able to view the rooms. Managed by the local council on behalf of the Trust, they are often used for civil functions, consequently remaining shut. When I visited recently the rooms were closed for a whole week due to a conference. Many visitors, including a Jane Austen fan from Australia, were understandably disappointed; trying to appease, an official commented that ‘the Assembly Rooms are a working building, not a museum’.

Beneath the Assembly Rooms is the Fashion Museum (note that National Trust members need to pay) where a vast collection of contemporary and historical dress from the past 400 years is showcased. Naturally, there’s a large collection of clothes from the Georgian period, all displayed on dressed figures, plus lots of hats, gloves and accessories. Visitors, both children and adults, may try on corsets and crinoline petticoats. Regularly changing temporary exhibitions take place too.

Museums of Bath

It’s a fascinating collection of social history, with rooms and tools laid out just as they were when the last shift bell rang.

For something a little grittier, the Museum of Bath at Work illustrates 2,000 years of earning a living in the city. The museum is housed in Bowler’s workshops, opened in 1872, an old engineering and brass foundry where nothing that looked vaguely useful was ever thrown away. Consequently the contents are all there. Changing with the times, the company moved into fizzy pop manufacture, so it contains plenty of machines, bottles and drinks labels too.

It’s a fascinating collection of social history, with rooms and tools laid out just as they were when the last shift bell rang, where belts, pulleys, cogs and levers vie for attention. You purchase your ticket at a solid wooden counter in the old stores, packed with brass this and iron that. Furniture-making workshops have been reconstructed from Keevil & Son, renowned in Bath from the 18th century for cabinet making and later for fitting out department stores and ocean liners. The quarrying of Bath stone is, of course, highlighted, as well as Plasticine, which was invented and made in Bath. There’s also the Bath Chair, the Bath Oliver biscuit and numerous other products developed off the back of the high-class ‘medical’ tourist industry. Providing interest for hours, to my mind it’s one of the most absorbing museums in the city.

However, it’s closely rivalled by the Museum of Bath Architecture, where visitors can discover how the city was transformed during Georgian times. It amply fleshes out the background to the rebuilding, with information on the principles of Palladian architecture and the ideologies of John Wood the Elder and his son. The construction of a Georgian house and street are illustrated through original materials, with masonry, street signs, ironmongery, railings, street lighting, plasterwork, tiling and architectural decoration featuring throughout the museum. A giant scale model gives an insight into the layout of the city.

Walcot Street & London Road

The long street, running parallel with the River Avon, has a character of its own and is filled with creativity.

The bohemian side to Bath is shown in Walcot Street together with its continuation, London Road. The long street, running parallel with the River Avon, has a character of its own and is filled with creativity: artisan art-and-craft workshops, furniture, upholstery and interior design showrooms, paintings, architectural salvage yards and the odd eatery.

On the west side of the street is Bath Aqua Glass – glassware, inspired by the Roman heritage of the city, is handmade on the premises; the products are characteristically coloured by adding copper oxide to the molten glass. You can visit to watch the craftsmen handling the red-hot glass, as they roll and form the molten liquid like sticky toffee; this is the place to visit for warmth in the depths of winter. Whatever piece is being made during the demonstration can be dated and personalised while you’re there. Having a go at glass blowing is a possibility – indeed, there are various half-day courses in glassblowing and stained glass – and there’s always the added bonus of buying factory seconds at reduced prices.