To help us indulge in a little escapism, we’ve been asking our authors for comic or revealing moments from their life on the road. Here, Outer Hebrides author Mark Rowe explains the lengths he had to go to in order to board a flight home from the island of Barra.

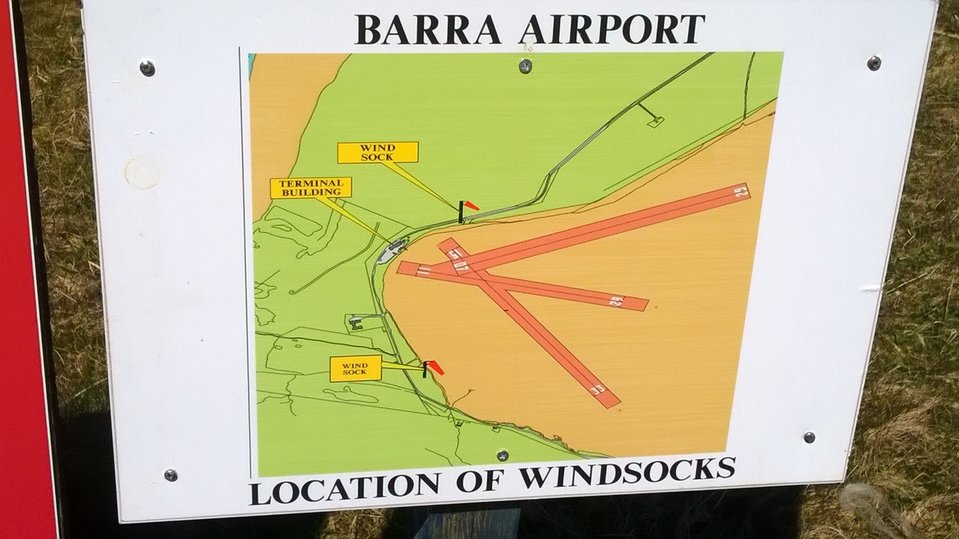

The sun was shining and, like a theatre curtain drawing aside to reveal the stage, the sea had retreated to expose the vast sands of Tràigh Mhòr on the northern edge of Barra in the Outer Hebrides. The main act, the world’s only scheduled beach landing by a commercial aircraft, was due.

In fact, it was overdue.

I’d spent three weeks on the southern islands of the Outer Hebrides researching my guidebook. Now, laden with outdoor gear, cameras, notebooks and a large side of hot-smoked salmon, I was keen to get home.

A doughty Twin Otter wobbles its way twice daily between Barra and Glasgow. I was on the second flight but, owing to what airlines always coyly describe as ‘a technical issue’, the first flight had not even arrived. The second was clearly going to be so late that I would miss my connection to Bristol. A night in Glasgow airport beckoned.

‘Oh dear,’ sighed the Loganair check-in assistant, ‘I wish you’d got here five minutes earlier. There was a seat free then.’

We went through the standard routine. Was space likely to emerge? Could she ask passengers booked on the first flight if they would mind switching to the second? Might the second flight make up time? No, no and no.

The tear-jerking scenario of crestfallen children mewing softly into their pillows that night as daddy failed to materialise also failed to cut it.

Like a foiled python I slunk back to my table, consoling myself with a slice of homemade carrot cake and a cappuccino from what café manager Sharon Cox heralded as ‘Barra’s only espresso machine made in Birmingham’. Barra airport does things differently and despite my predicament I was rather liking the place. Something would turn up, I felt.

And so it proved. The universal surliness of airport check-in staff is not the product of mere chance: identified shortly after birth, they are removed from their parents and reared in the etiquette of saying ‘no’ in 20 languages. The lady from Loganair was a glorious exception. ‘I have a plan,’ said a voice at my elbow. ‘I just called the pilot about you.’

Called the pilot!? Imagine that happening on a transatlantic flight, or on a London–Singapore service 30,000ft above the Indian Ocean.

Having paused to allow this to sink in, she added, ‘He thinks he can get you on the flight, but your baggage absolutely must not exceed 20kg.’ Even before I thumped my suitcase on the scales I intuitively knew it weighed 21.1kg.

Our lady from Loganair sighed. She was on a mission. She wanted me to catch the flight. She stared hard at my suitcase, hands on her hips.

‘Is there anything disposable in there?’ she inquired archly, pigeonholing me as someone likely to be carrying a good deal of dirty and dispensable clothing.

Well, I replied, I have this salmon.

I should point out that this was not any old salmon. I’d purchased it from Barratlantic, Barra’s leading – only – fish factory. In a part of the world where all salmon is glorious, Barratlantic is head, shoulders and gills above the competition.

We placed the smoked carcass reverentially on the scales: at 1.5kg a solution was at hand. I was reluctant to part with it but, I was faced with a plastic seat for a bed in Glasgow airport.

I opted for the heroic. I would eat the salmon.

‘You can’t eat a whole salmon,’ pointed out my guardian from Loganair. ‘No-one can eat a whole salmon.’

Altruism took over. ‘Let’s offer it around then,’ I declared. The suggestion was received with universal nods of heads among the waiting passengers.

We borrowed a carving knife from the café but as I set to carve the beast, a voice of reason piped up from the nearest table. ‘If we eat the salmon, are we not then collectively 1.5kg heavier? We’re not solving your weight issue, just sharing the problem.’ A dozen pairs of eyes stared balefully at the salmon as puppies might at a bone withdrawn by a butcher.

The Loganair heroine was staring hard at my feet. Her arms were now folded. ‘How about your boots?’ she suggested. ‘They look like they’ve had their time.’ She had a point: they had been stitched together so often that, like an ageing jumbo jet, none of the original fuselage remained.

Only one of them was laced, the other held in place by a cocktail of soil from several geological eras. Naturally I had taken the view they had a good ten years left in them but, weighing in at 3kg, they were heavy enough for me to get home and even buy another side of salmon.

I said a quiet goodbye to them and placed them in a bin. Problem solved. A couple of passengers were still looking shiftily at my salmon though.

We weren’t done yet. An even happier ending emerged. I was to return home not just with salmon but my boots. Our Loganair lady again: ‘I just had another chat with the captain. The winds mean he can land without circling around the island so he’s got a few more kilos of fuel to play with for the return journey. You can take your boots out of the bin.’

Half an hour later, we took off, bouncing down the beach past cockle pickers and startled oystercatchers, my salmon and boots tucked in the hold. The journey was stunning, views of Rùm, Coll, Tiree and Canna far below.

From my seat I could see the pilot and his colleague constantly at work, looking out of windows, pulling levers, flicking switches. They were often speaking to air traffic control. I assume they were taking routings and height instructions. Or maybe they were being asked if they could accommodate another salmon.