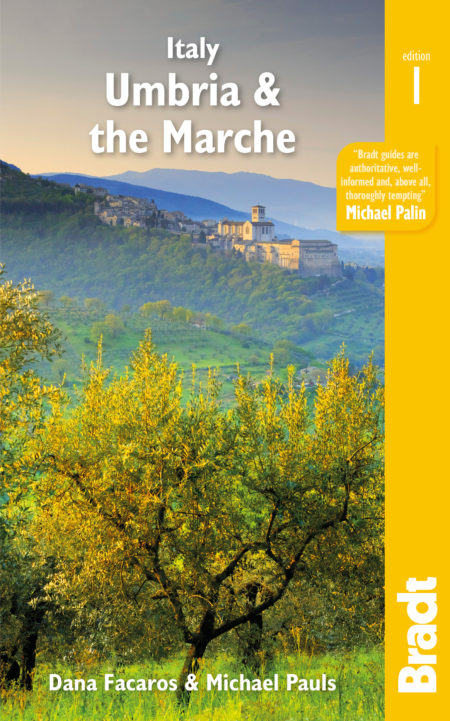

There’s so much to like about Umbria and the Marche, but for many people it’s the countryside, the dream-like landscapes painted by Piero della Francesca and Perugino, that sets their imagination into another gear.

Dana Facaros and Michael Pauls, authors of Italy: Umbria & the Marche

From a thousand different viewpoints you can see several medieval hill towns, castles, churches and farms at the same time, one behind the other, in a rolling carpet of vines and olives vanishing into the bluish haze of the horizon, in autumn swirled in romantic mists. Walk a minute, drive around a curve, and the view changes yet again. Purple mountains loom in the distance; in the Marche, the deep blue of the Adriatic glitters on the horizon.

Besides their landscapes and hill towns, these two central Italian regions have much in common: both are major producers of truffles, olive oil and wine; there are wealthy Roman villas and archaeological sites to explore and some of the finest medieval and Renaissance art in the world. Often compared to Tuscany, Umbria and the Marche had a different destiny, as the massive gravitational force that is Rome eventually pulled their once proud city states into the stultifying blanket of the Papal States – which had the effect of preserving them in aspic for centuries. Unfortunately, Umbria and the Marche also share the same earthquakes, lastly in 2016.

But they are different too: since the 19th century Umbria has been celebrated as the ‘Green Heart of Italy’, the most mystical of colours; as a nun on the bus once told us, ‘Umbria speaks in silences.’ It was a spiritual powerhouse, producing more than its share of major saints, starting with Benedict, the founder of western monasticism, and Francis, the gentlest of revolutionaries. Perugia, Assisi, Orvieto, Gubbio, Spoleto, Città di Castello, Todi and a hundred smaller towns are beautiful and crammed with treasures until time stopped around 1530 (although they do have a surprising amount of contemporary art).

The Marche – often translated as the ‘Marches’ in English – likes to call itself ‘Italy in one region’. Everything we love about the Big Boot is concentrated here, from long sandy beaches to glorious mountains, arty hill towns, bijou opera theatres and festivals. Two truly exceptional art cities, Urbino in the north and Ascoli Piceno in the south, occupy either end, while in between are dozens of towns – Pesaro, Fano, Macerata, Fermo, Fabriano, Jesi, Loreto, Tolentino, Senigallia, Sassoferrato and many others that are still off the mass tourism radar, with more than their share of secrets, just waiting to be discovered.

For more information, check out our guide to Umbria & the Marche

Food and drink in Umbria & the Marche

Regional traditions are strong in Italy, not only in dialect but in the kitchen. Umbria and the Marche share many traditional dishes but also diverge in interesting ways.

Umbria offers good, honest dishes, based on superb local ingredients: olive oil, game, mushrooms, truffles and salumi (cured meats) from the acorn-fed pigs of Norcia, so renowned that all over Italy a shop selling salumi is called a norcineria. Umbrians even maintain local traditions when you wish they wouldn’t – especially in the case of their hard salt-less bread (although it is delicious as bruschetta grilled over an open fire, rubbed with garlic and drizzled with olive oil or the favourite appetiser, crostini – thin slices of toast topped with a piquant pâté spread of chicken livers, or veal spleen (milza), anchovies, capers and lemons, or truffles). The other traditional antipasto is a platter (afettati) of prosciutto, salami and capocollo (cured neck of pork, rolled in pepper).

Umbrians love their pasta, with good reason. There are subtle variations and names for the region’s round or square-shaped fat homemade spaghetti (ciriole, manfricoli, pici, umbricelli or strangozzi). Among the favourite sauces are funghi (mushrooms, usually porcini), or tartufi (with truffles) and wild asparagus in May and June (it’s also excellent in omelettes). Other favourite sauces are all’amatriciana, made with tomatoes and bacon, or its close cousin, spaghetti col rancetto, from Spoleto. Many restaurants serve pappardelle al cinghiale, wide pasta ribbons with a sauce made from wild boar, red wine, juniper berries and tomatoes. In northern Umbria look for strascinati, macaroni served with sausage, eggs and cheese. The real test of an Umbrian chef is eggs with truffles; risotto with truffles or mushrooms is also delicious.

Umbria has been a wine region ever since the Etruscans. Although it has its share of DOC wines, the whole region since the 1990s has been designated Umbria IGT (Indicazione Geografica Tipica), which has encouraged winemakers to experiment and improve old table wines. Trebbiano and Grechetto grapes star in the region’s famous DOC Orvieto, a delicate white wine, dry with a slightly bitter aftertaste; Orvieto Classico comes from around the Paglia River.

But reds are coming on strong; nearly a quarter of all grapes grown are now Sangiovese, the star of DOCG Torgiano Rosso Riserva, yielding magnificent dry, full-bodied reds that can take years of ageing. The other great red is DOCG Sagrantino di Montefalco, one of Italy’s greatest wines, made with at least 95% native black Sagrantino; the dessert Sagrantino Passito, made from raisins, is superb.

The Marche’s cuisine is as varied as its landscapes. All of Italy loves olive all’ascolana – the stuffed, breaded and fried olives from Ascoli Piceno. Local cured meats come from the mountains: DOP prosciutto di Carpegna and ciauscolo, a soft salame cold-smoked over juniper, and its cousin fegatino, a soft liver sausage.

Among the pastas look for fregnaccia (badly cut strips, often served with ragù), bringoli (fat homemade pasta) and some unusual ones: pincinelle, made from bread dough, tacconi made with broad bean flour, lumachelle (or passatelli), fat dumplings made from eggs, breadcrumbs, and parmesan, and cresc-tajat, pasta diamonds made from polenta, served with borlotti beans and pork. Then there’s vincisgrassi, the Rolls-Royce of lasagnes, with ragù, béchamel, tomatoes, chicken giblets and livers, nutmeg and parmesan.

Main courses include coniglio imporchettato (deboned rabbit stuffed with truffles and sausage); you might also find rabbit (or chicken) alla ‘ngip e ‘ngiap (simmered in garlic, white wine, rosemary, sage and chilli flakes) or in potacchio, braised in olive oil, rosemary, garlic and tomatoes. Lamb is popular, most exotically in Ascoli’s fritto misto (deep fried chops, artichokes, courgettes, red peppers, olive ascolane and cubes of cream). Pasticciata alla marchigiana is a beef roast in sauce.

The seafood is superb – Conero mussels are famous. Nearly every town along the Adriatic has its own variations on brodeto, the fish stew using 13 kinds of fish. Ancona is also renowned for stock fish (wind-dried cod – a taste acquired in the Middle Ages after a Venetian shipwrecked in Norway and brought some back to Italy); stoccofisso all’Anconetana, made with potatoes, tomatoes and Verdicchio wine, even has its own academy to maintain its standards.

Health and safety in Umbria & the Marche

In most cases, EU citizens with an EHIC (European Health Insurance Card) are entitled to free care in Italy from the national health system, the SSN (Servizio Sanitario Nazionale). Non-EU citizens should take out comprehensive travel insurance, and make sure the policy covers cancellations. As the UK is no longer a member of the European Union, arrangements for UK citizens may change. Check before travelling.

There will be a hospital, clinic or health unit (Azienda Sanitaria) with a pronto soccorso (casualty/first-aid department) in every town of any size. Pharmacy staff are trained to assist with minor problems. If a pharmacy is closed, look for the card in the window with the schedule of the farmacia di turno (the closest one open. Most doctors and pharmacists speak rudimentary English.

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available here. For other journey preparation information, consult Travel Health Pro or CDC: Traveller’s Health. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Umbria and the Marche have a very low crime rate, but it’s always best to take the same precautions you would take elsewhere.

Female travellers

Women travelling alone should not encounter any problems. If possible, try to avoid arriving or leaving big city stations late at night. There have been complaints of harassment, though no more or less than in any other European city.

LGBTQ+ travellers

In country towns and villages, a certain amount of discretion may be called for as you may encounter confusion, especially among the elderly. A list of LGBTQ+ friendly hotels, B&Bs, bars, and more in Italy is available here.

Travelling with children

Italians adore children, and you shouldn’t encounter any problems travelling with yours. However, if you are travelling with minor children with different surnames, you may need proof of guardianship. Contact your Italian consulate before you leave.

Many hotels and agriturismi offer family rooms. Under 18s are usually given free or half-price admission in museums. Children aged 4–11 years inclusive pay the child fare on Trenitalia; on long-distance trains those under 15 qualify for the child fare. Children under four travel for free, although you’ll still have to pay a small fee for a reservation.

Travel and visas in Umbria & the Marche

Visas

Citizens of EU member states and holders of passports from some 50 nations do not need a visa for stays of 90 days or less. These include Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Israel, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, South Korea, Singapore, Switzerland, the UK and the USA. As the UK is no longer a member of the European Union, documentation requirements for UK citizens may change – check before travelling.

Theoretically, all foreigners are required to register their presence with the police within eight days of their arrival, but in practice few bother; in any case, your accommodation will take your passport for this purpose. Be aware, however, that if you are a non-EU citizen and get in a jam with the police, they can take your failure to report your arrival as evidence that you have already overstayed the legal period.

EU citizens can stay beyond 90 days if they have employment, sufficient resources, or an approved course of study. Officially they are required to fill out a form at the local police station or anagrafe (registry office).

For citizens of non-EU countries (including non-EU family members of EU citizens) extending your stay beyond 90 days means you’ll need to arrive in Italy with an entry visa, before applying for a permesso di soggiorno through the provincial Questura (state police office). An entry visa is based on study, work and elective residence, few of which are entirely clear in the regulations. Whichever you need, expect the rules to be complex, onerous and confusing.

Getting there and away

By air

There are small regional airports in Perugia and Ancona, both of which are served by direct flights from the UK, but flying into Rome is a good option, too, with convenient road, rail and bus links to Umbria and the Marche. Bologna airport could be an option for the Marche, with direct trains to Pesaro in 75 minutes. Which airlines will go where when is difficult to predict; Sky Scanner is a good place to check for the latest information.

By train

From the UK, take the Eurostar across the Channel and connect with a fast train. Travelling from London St Pancras to Perugia can take as little as 20 hours, changing in Paris (Gare du Nord to Gare de Lyon); see here for options, although it’s almost impossible to find a train cheaper than a flight. Trenitalia operates much of Italy’s rail network. All high-speed Freccia (‘arrow’) trains have reserved seats; buy e-tickets online or from the machines at the stations.

By sea

Ancona is major Adriatic port with ferry links from Croatia, Greece, Albania and North Macedonia.

By car

It’s 1,644km from London to Perugia by way of the Channel Tunnel, France, Switzerland and Milan, taking a minimum of 20 hours and costing approximately €150 in fuel and €200 in tolls and vignettes, not to mention an overnight stay. In August, especially at weekends when roads are busy, it can take much longer. Once in Italy, you’ll be on an excellent network of motorways.

When to visit Umbria & the Marche

When to visit

With their dazzling art cities and landscapes, mountains and beaches, Umbria and the Marche offer something for every season. Spring, especially May is pleasantly warm, as fields and gardens brim with wildflowers, and fireflies dance in the meadows. Autumn, too, is a classic time to visit, from mid-September to October; before the winter rains begin and the air is clear, the colours intense.

The hills are never less than beautiful, but in October they’re extraordinary. Summer is perfect for lolling on Adriatic beaches, high mountain treks and long evenings out under the stars; and it’s also the season of festivals. In winter, you can have the great museums and churches to yourself; it seldom snows but may rain for days at a time, when mists float in the valleys and turn hill towns into islands in the clouds.

The regional tourist offices’ websites for Umbria and the Marche are in English and packed with itinerary possibilities and suggestions. Accommodation, holidays, guided visits and excursions can also be booked via Umbria Tourism.

Climate

Umbria and the Marche’s climate is temperate – Mediterranean near the coast and in the lower valleys but considerably cooler and Continental up in the mountains; the higher Apennines have enough snow to support several ski resorts.

Summers are hot and humid, and temperatures can reach the high 30s (°C). The mountains also get a considerable amount of rain, with up to 1,500mm in a year, while the Adriatic coast receives roughly half that.

What to see and do in Umbria and the Marche

Assisi

Visible for miles around, Assisi sweeps along the flanks of Monte Subasio like a pink ship sailing over the green sea valley below. On any given summer’s day, you’ll see coachloads perusing stands selling friar-shaped salt and pepper shakers, intermingled with flocks of serene Franciscans and nuns from Africa or Missouri or Bavaria, having the time of their lives visiting a place that, more than Rome, is the symbol of a living faith. And it’s true that something simple and good and joyful has survived in Assisi in spite of the odds.

Tragically, in September 1997, earthquakes brought the roof of the Basilica of St Francis down, killing two friars and two journalists who were examining the damage caused by the day’s first shock. The builders had given the basilica the flexibility to withstand earthquakes, but restorers over the centuries had been too lazy to haul out all the rubble they had created in the breathing space between the frescoed vaults and the walls; ultimately, the weight proved too great.

Although the damage hit a wide area in Umbria and the Marche, for most of the world these were the ‘Assisi earthquakes’. Millions poured in for restoration, with priority given to a ‘Jubilee list’ of monuments on the official pilgrimage route of the Holy Year 2000. Assisi vowed it would reopen by Christmas 1999, and it did – an impressive feat, especially in Italy where projects on that scale usually take decades to complete. It was the first major monument anywhere with anti-seismic bundles of wires of ‘shape-memory alloys’ made of titanium and nickel woven in the walls. Invented by the aeronautics industry in 1951, the alloys are used in shock absorbers – in this case, a very big shock absorber, which should give the basilica 50% more ‘give’.

Today Assisi is in better condition than ever. Even buildings that were not actually damaged have been restored. It’s an ill wind … and since 2000, UNESCO designated Franciscan Assisi a World Heritage Site.

Basilica di San Francesco

In transforming the Franciscans into a doctrinally safe arm of Catholicism, the popes had the invaluable aid of Francis’s successor, Vicar-General Brother Elias, an organisation man, something of an epicurean and friend of Frederick II. Elias’s methods caused the first split within the Franciscans. This monumental complex, begun the day after Francis’s canonisation in 1228 when Gregory IX laid the cornerstone, was a major cause of contention. Nothing could have been further removed from the philosophy of Francis; yet nothing could have been more successful in perpetuating his memory and teaching.

From the beginning, the popes were entirely behind the basilica. They paid for it by promoting a sale of indulgences, and to this day it belongs to the Vatican (although thanks to the Lateran Treaty of 1929, the Italian State is responsible for the upkeep). Elias himself may have supplied the design – the lower basilica does have an amateurish, clumsy form. The beautiful campanile dates from 1239; the completed basilica was consecrated by Innocent IV in 1253. Behind it, on huge buttressed vaults, is the enormous 15th-century convent built by Sixtus IV, now a missionary college. The usual approach is through the Piazza Inferiore di San Francesco, lined with arcades where medieval pilgrims bought their souvenirs.

‘I would give all the churches in Rome for this cave,’ wrote Hippolyte Taine, 19th-century French critic and one of the first moderns to appreciate this jewel. Because of its partially underground location, the lower church has no façade, but it does have a grand Renaissance portico of 1487 to protect the Gothic portal. Whoever was responsible, the church was designed to hold the saint’s body, and with its low, dimly illuminated vaults, it certainly resembles a crypt. It is confusing at first in its overwhelming detail, and a bit claustrophobic, yet tucked in here are some of Italy’s finest 13th- and 14th-century frescoes.

In contrast with the lower church, the upper church with its big rose window and false front gable is strikingly bright and airy, filled with frescoes that emphasise its perfectly balanced proportions. This is Gothic reduced to its basics. The medieval Italians, who never really took to the northern style and regarded flamboyant vaults, spires and buttresses as barbaric, nevertheless did appreciate the possibilities the new building techniques offered to create a single open space.

The upper church, whoever designed it, became the great prototype of Italian Gothic, the model for countless Franciscan and Dominican churches: here all the features emphasised by northern architects are minimalised to provide a perfect framework for the frescoes in a revolutionary synthesis of art and architecture. The space, the simplicity and the easy-to-‘read’ illustrations were just what a preaching order required. Although the frescoes steal all the thunder, give a few minutes to the beautiful 13th-century stained glass, considered the finest in medieval Italy.

Gubbio

In a way, Gubbio is what Umbria has always wanted to be: stony, taciturn and mystical, a tough mountain town that fought its own battles until destiny and the popes caught up with it – also a town of culture, one with its own school of painters. For a city over 2,500 years old, it still seems like a frontier town, an elemental place that sticks in the memory: the green mountainside, a rushing stream, straight rows of rugged grey stone houses. On Gubbio’s windy slopes, the hard-edged brilliance of the Italian Middle Ages is clear and tangible.

It’s touristy now, but it deserves a soft retirement, and makes a great base for visiting this corner of Umbria, near the Parco Naturale del Monte Cucco with its caves, gorges, and legendary updrafts. Gubbio is a name geologists might recognise: its Gola del Bottaccione is world famous. Fans of Italian television may also recognise the city as the setting for the Don Matteo series, starring Terence Hill as the town’s crime-solving priest.

Museo Civico

On the first floor, in the enormous barrel-vaulted Sala dell’Arengo, where assemblies of the people were held, is this cluttered, fascinating museum that resembles an indoor flea market, unchanged since it was first opened in 1909, with antiquities, tombstones, sarcophagi and crossbows deposited every which way. There is a Roman inscription – Governor Gnaeus Satirus Rufus bragging how much he spent to embellish the town. On the wall is a 14th-century fresco of the Madonna, Child and SS John the Baptist and Ubaldo, attributed to the leading painter of the era, Mello da Gubbio.

The former chapel is reserved for the seven bronze Eugubine (or Iguvine) Tablets, far and away the most important inscriptions ever found in the Umbrian language. Although engraved in the 3rd–1st centuries BC, the texts are far older, dealing religious rites and purifications required to keep the gods onside.

Festa dei Ceri

Gubbio’s medieval festivals fill its solemn streets with colour and exuberance. Oldest of them all is the Festa dei Ceri, held every 15 May in honour of patron saint Ubaldo. Although first documented a couple of years after Ubaldo saved the city from Emperor Frederick, the festival has the uninhibited trappings of a pagan celebration that may have pre-dated the good bishop’s heroism. The ceri (candles) are three wooden, octagonal towers some 4m high, each topped by a wax saint representing a guild – Sant’Ubaldo (builders, dressed in yellow), San Giorgio (artisans, in blue) and Sant’Antonio Abate (farmers, in green).

On 15 May, following a mass, the wax saints are brought out of San Francesco della Pace and taken in a procession to the ceri in Piazza Grande, where they are affixed to the top of the ‘candles’. A second procession from the Porta Castello heads up to Piazza Grande, followed by a big banquet for participants in the Palazzo dei Consoli. At 4 o’clock in the afternoon, the bishop arrives and ‘baptises’ the ceri with jug of water. The race begins at 18.00; ten bearers hoist their respective cero on their shoulders then take off pell-mell up the streets before continuing up the mountain to the church of Sant’Ubaldo. The porters constantly peel off and new ones join – a neat trick done without slowing the pace. In the evening, the wax saints are returned to their home in San Francesco della Pace in a candlelit procession.

Lake Trasimeno

Italy’s fourth largest lake, Trasimeno (45km in circumference) has a subtle charm, sleepy, placid and shallow, almost marshy in places. Large enough to create its own soft micro-climate, it shimmers like a mirror embedded in gentle rolling hills, its soft light captured over and over again in the finest works of its greatest artist, Perugino. The Etruscans of Camars (Chiusi) coveted the lake for its fish and the fertility of its shores, and around the time of their famous king Lars Porsena (the bad guy in Macaulay’s Horatio at the Bridge) they founded Perugia to control it. In the 12th and 13th centuries, wars were fought for its eels. Napoleon took one look at it and wondered how to drain it.

Hans Christian Andersen, drawing on his own travels, put Umbria’s Trasimeno in one of his fairy tales, The Galoshes of Fortune – how beautiful it was, but how poor the people were, and how wretched their lives among the swarms of flies, mosquitoes and malaria. A post-war dose of American DDT wiped out the latter, and stocking the lake with insect-eating fish has helped, and the lake has since become a modest resort – the Umbrian Riviera and centre of the Parco Regionale del Lago Trasimeno.

Never one to cooperate fully with humanity, Trasimeno, with a maximum depth of 6m, is now trying to become a peat bog. But fishermen skim over its waters, seeking eels, perch, tench, shad and carp. Ducks, cormorants and kingfishers love it, and water lilies float among the reeds.

Magione

Like any place within Perugia’s radius, Magione spent the Middle Ages fighting. The recently restored 12th-century Torre dei Lambardi built by the Knights of St John (now of Malta) on top of the town, is now equipped with a lift for the lovely views.

On the edge of Magione, the Castello dei Cavalieri di Malta (1420), is still owned by the Knights as the centre of their wine estate. In late July it hosts the Congiura, a re- enactment of a failed plot here against Cesare Borgia in 1502, recorded by Niccolò Machiavelli. The knights’ church, San Giovanni, was damaged in the last war, and was rebuilt and frescoed in a traditional manner by Gerardo Dottori in 1947. On the main street, the little church of the Madonna delle Grazie has a lovely 14th-century fresco of the Madonna Enthroned by Bartolo di Fredi.

Tuoro sul Trasimeno

Tuoro grew up in the Middle Ages near the Castello di Montegualandro, a refuge for citizens whose town was attacked by every Tom, Dick and Harry crossing the Italian peninsula. But of all the battles that occurred here, it is famous for the one where Hannibal almost brought Rome to its knees. You can explore the battlefield by car or foot, along the 13 stations of the Percorso Storico Archeologico della Battaglia, dotted with viewing platforms, explanatory notes and maps that help bring it to life, along with the four major theories on how and where the various stages of the battle unfolded.

Tuoro has decorated its lakeshore with something unexpected: Pietro Cascella’s Campo del Sole (1985–89), a ‘solar temple’ of 27 sandstone pillars, each about 14m high and sculpted by a different artist, arranged in a wide spiral like a forest of idols to a preposterous god.

Castiglione del Lago

Among the silvery olive groves that soften the west shore of Trasimeno – the beginning of an agricultural plain stretching into Tuscany – juts the promontory of Castiglione del Lago. In ancient times, when the lake was much bigger, this was an island. Frederick II destroyed medieval Castiglione for being an ally of Guelph Perugia, then ordered Fra Elia Coppi to lay out the streets and squares that are still the core of the old town. Afterwards, Castiglione kept siding with Cortona, causing no end of friction with Perugia until 1490, when it came under the Baglioni, who during their brief period of glory hosted Machiavelli and Leonardo da Vinci here.

Eventually it was recovered by the popes, one of whom, Julius III, gave it to his sister. In 1550, her son, the celebrated condottiero Ascanio della Corgna and husband of Giovanna Baglioni, became the first in a series of dukes who ruled the lake as an independent duchy until 1648. In 1563, during this Ruritanian interlude, architect Vignola (or some say Galeazzo Alessi) designed the Palazzo della Corgna. The façade was never finished, but the piano nobile retains its fetching late Renaissance frescoes by Pomarancio; one shows the Battle of Trasimeno, and others the Deeds of Ascanio including the Battle of Lepanto, in which Ascanio distinguished himself and a famous duel – he was so renowned a swordsman that crowds came to watch him fight.

Perugia

Balanced on a commanding hill high over the Tiber valley, Perugia adroitly juggles several roles: that of an ancient hill town, a magnificent città d’arte, a university centre and a slick cosmopolitan city. It is a fascinating place and a fitting capital for Umbria. Splendid monuments from the Etruscan era to the Late Renaissance stand cheek to jowl; its gallery contains the region’s finest art; but in the alleyways cats sleep undisturbed. Thanks to Lake Trasimeno, just a hop and a skip to the west, Perugia has a ‘riviera’ of its very own, dotted with bijou islands and mighty castles; Perugino was born just to the south of the city in Città della Pieve and made these bluish-green landscapes his own.

Yet its sun-filled present is haunted by sinister shadows from the past. Four medieval popes died in Perugia. One did himself in – stuffing his gut with Lake Trasimeno eels – but for the other three the verdict was poison. And then there were the Baglioni, the family who ruled the city for a time and who were so dangerous that they nearly exterminated themselves. Blissful Assisi, perfumed with the odour of sanctity, may only be over the next hill, but Perugia in the old days was full of trouble. But in Italy creativity and feistiness often went hand in hand, and the city has contributed more than its share to culture and art. Just as remarkable as the people is the stage they act on: the oldest, most romantically medieval streets and squares in Italy.

A strange thing happened to Perugia in the middle of its rough-house career in the 1500s, when the popes took firm control. Art, scholarship, trade and civic life quickly withered, and the town’s penchant for violence was rocked to sleep under a warm blanket of Hail Marys. Look at Perugia now, its people famed for their politeness, urbanity and good taste. They make their living from chocolates and teaching Italian language and culture to foreigners. Maybe a few centuries under the pope was just what they needed.

Discover the city on foot

Walking in Perugia is a delight, although you may find yourself out of breath. In the oldest parts, densely packed and half-covered with arches and passageways, Perugia often seems like one big building. Its difficult topography has been mastered with some cleverness with elevators or escalators to carry you from one part to another. These tend to be on the edges of town, where parks have been strung along the cliffs to take advantage of unusable land.

Enjoy the street names: Via Curiosa (Curious St), Via Perduta (Lost St), Via Piacevole (Pleasant St), Via Pericolosa (Dangerous St), among many others. And look for details – carved symbols and coats of arms. One local peculiarity is the narrow Porta del Morte, ‘Death’s Door’, used only to carry out the dead, and bricked up the rest of the time – where death has once passed, the superstition went, he might pass again. In some houses these doors were the only access to the upper floors, with ladders inside that could be pulled up in emergencies.

Piazza IV Novembre

Magnificent, time-worn Piazza IV Novembre, once the setting for countless riots and street battles, remains the heart and soul of Perugia. As in many Umbrian cities, the old town hall, symbol of the comune, entirely upstages the cathedral, but here, the two stare at each other over Italy’s most beautiful medieval fountain, the 25-sided polygonal pink and white Fontana Maggiore, designed in the 1270s by Fra Bevignate.

The occasion was the construction of Perugia’s first aqueduct since Roman times, and the Priors commissioned the top chisel-masters of the day, Nicola Pisano and his son Giovanni to sculpt the 48 double relief-panels around the lower basin. The more you look, the more you realise the subtlety and dynamism of Fra Bevignate’s design, particularly the way in which the panels of the lower basin are never congruent, but pull the eye along.

Festivals

Perugia hosts several major events, starting with Italy’s most important Jazz Festival in July, with such alumni as the late Stan Getz and Wynton Marsalis. In mid-June, Perugia 1416 celebrates the Battle of Sant’Egidio with processions, competitions between the rioni and other events. Late June is time for the Trasimeno Music Festival, founded by Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt, followed in July and August by the Trasimeno Blues Festival.

The summer Music Fest Perugia features classical music in the churches, and the Destate La Notte ‘Wake Up the Night’ runs from July through September, with late-night events of all kinds. Perugia Musica Classica sponsors September’s wonderful Sagra Musicale Umbra in historic locations around the region and concerts all winter long. Thousands join in October’s Marcia della Pace (second Sunday in October), the peace march to Assisi held every year since 1963. Eurochocolate, the massive chocolate festival, follows, and then in the first week of November it’s the Fiera dei Morti in Pian di Massiano – the oldest-surviving fair in Central Italy.

San Marino

While in the Marche, you may want to pop into one of the world’s smallest countries – the only medieval Italian comune that managed after all these centuries to maintain its independence. The 33,300 Sammarinese once made a living from agriculture and peddling postage stamps to collectors.

Now, with their medieval streets crowded with day-trippers from the beaches, the Sammarinese have been unable to resist the temptation to order some bright medieval costumes and open souvenir stands and ‘duty-free’ shops. Today they have one of the highest average incomes in Europe, and the men have the highest life expectancy in the world. They must be doing something right.

A potted history of the world’s smallest and oldest republic

According to legend, San Marino was founded on the easily defensible slopes of Monte Titano by a Christian stonecutter named Marinus, fleeing from the persecutions of Diocletian in AD 310. ‘Overlooked’ by history, as the Sammarinese charmingly put it, the little community had the peace to evolve its medieval democratic institutions; its constitution dates from 1243 when the first pair of ‘consuls’ was elected by a popular assembly. The consuls are now called Captains Regent, but little else has changed. Twice, in 1503 and 1739, the Republic was invaded by papal forces, and independence was preserved only by good luck and nearly always choosing the winning side.

Napoleon, passing through in 1797, found San Marino amusing, and half- seriously offered to enlarge its boundaries, a proposal that was politely declined. It felt secure enough to shelter Garibaldi, his wife Anita and 1,500 of his followers, fleeing Rome after the fall of the republic of 1849, with an Austrian army in pursuit. When the Austrians surrounded San Marino, demanding their expulsion, Garibaldi dissolved his army in the night and made a run for the coast.

Since then, the republic has been an island of peace, taking in hundreds of refugees in World War II. In 2008 the historic centre was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site as ‘an exceptional testimony of the establishment of a representative democracy based on civic autonomy and self-governance, with a unique, uninterrupted continuity as the capital of an independent republic since the 13th century’. It last made the headlines in 2019, when it reached the Eurovision semi-finals with a dentist named Serhat singing ‘Say Na Na Na’.

Terni

As the home of St Valentine, Terni likes to call itself the ‘City of Love.’ It even has its own Niagara Falls for honeymooners: the green and misty Cascata delle Marmore, part of the beautiful Parco Fluviale del Nera that extends some 20km up the Valnerina, along with pretty Lake Piediluco.

For all that, you may not want to linger long in southern Umbria’s capital itself, but you might at least muster some respect for its accomplishments as the Manchester of Italy.

Set in a fertile plain, it was settled since the Iron Age; by the 7th century BC, it was the capital of the Umbrii Naharkum, best remembered as Gubbio’s sworn enemies. Terni’s name derives from Interamna Nahars (from inter amnes, ‘between two rivers’ – the confluence of the Nera and the torrential Serra). Conquered by the Romans in the 3rd century BC and a major station along the easterly route of the Via Flaminia, it was traditionally considered the birthplace of the historian Tacitus, although scholars now quibble that Terni’s was the more meagre Claudius Tacitus, Roman emperor for a year.

In 1867, as the city closest to the centre of Italy, it was intended to be the nation’s capital (this was before Rome was wrested from the occupying French), but even so, the idea flew like a penguin. If Italy’s politicians couldn’t appreciate Terni’s location, far from the vulnerable coasts and frontiers, the military certainly did. Its location on the Nera, and the vicinity of the Cascata delle Marmore, sealed its destiny. In the 1870s, the beautiful thundering waters were diverted for cheap hydro-electric power, a foundry was built, and in 1884 Italy’s first steel mill went up to build ships to pester Africa, pushing Umbria to lurch belatedly into the Industrial Revolution.

The population doubled in less than a decade, then tripled, and what had been an insignificant medieval town before Unification became Umbria’s second city. In the 1920s Terni scientists astounded the world with the first practical plastic. Terni also has the State Arms Factory (the rifle that killed JFK was manufactured here); these three industries together proved enough of an attraction for Allied air forces to smash 80% of the city flat in 108 air raids, which left more than 1,000 dead.

Terni’s industry quickly recovered, and it doesn’t just sit on its gritty laurels. The mills, now the ThyssenKrupp Acciai Speciali Terni, specialise in stainless steels. It has the medical, engineering and economics branches of the University of Perugia, hosts top stem cell, cancer and nano material research centres, and TERNI (Terni Enterprise for Research and New Industries) into alternative and high-tech green industries.

Cascata delle Marmore

One of Europe’s tallest (165m), most beautiful and most photographed waterfalls roars down the wooded precipice in three stages – when it’s running. Surprisingly, the Cascata is an artificial creation, albeit an ancient one. In 271BC, Curius Dentatus, best known as the conqueror of the Sabines and for having two sets of teeth, dug a channel to drain the marshlands of Rieti, diverting the Velino River into the Nera, although it wasn’t all smooth sailing.

By 54BC, during wet seasons, the Nera would flood Terni, leading to a fight between Rieti and Terni that came to no conclusion. The channel blocked up after the fall of Rome, leading to the return of swamps and disease around Rieti, until 1422 when a new channel was dug under the reign of Pope Gregory XII. The new channel had to be repaired in 1598; and yet another canal had to be dug in 1787.

Although the falls are usually swallowed up by hydro-electric turbines, the thundering waters are let down at regular times, at certain times on certain days each month. A warning siren sounds 15 minutes before they pull the switch, to warn swimmers to get out; try to be there to watch the trickle turn into a foaming avalanche.

Lago di Piediluco

This lovely lake – once part of the much larger Lacus Velinus before the creation of the Cascata delle Marmore, and now the capital of sport rowing in Italy – is formed by the rivers Velino and, somewhat surprisingly, the Nera (thanks to Mussolini’s scheme in the 1920s to channel waters from the upper river through an aqueduct to increase the hydro-electric power-giving force of the falls).

It zigzags in and out of wooded hills, one of which is crowned by a 12th-century fortress. The medieval village and modest resort village of Piediluco on the northeast shore has a couple of beaches where you can swim, although the water is pretty cold.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Umbria and the Marche: