Written by Philip Briggs

The names of the individual mountains in the Virunga chain reflect local perceptions © Ariadne Van Zandbergen, Africa Image Library

The names of the individual mountains in the Virunga chain reflect local perceptions © Ariadne Van Zandbergen, Africa Image Library

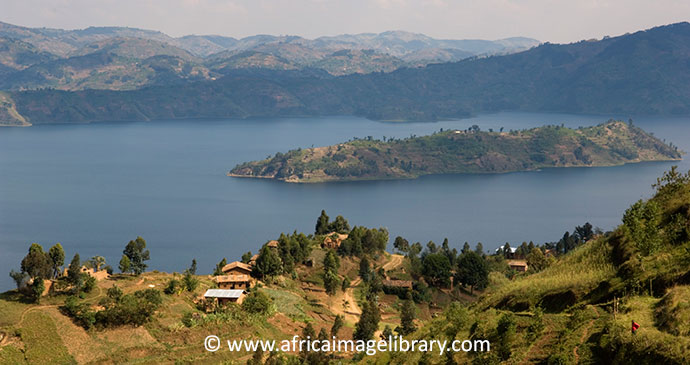

Straddling the borders of Uganda, Rwanda and the DRC, the Virungas are not a mountain range as such, but a chain of isolated freestanding volcanic cones strung along a fault line associated with the same geological process that formed the Rift Valley. Sometimes also referred to as the Birunga or Bufumbira Mountains, the chain comprises six inactive and three active volcanoes, all of which exceed 3,000m in altitude – the tallest being Karisimbi (4,507m), Mikeno (4,437m) and Muhabura (4,127m).

The names of the individual mountains in the Virunga chain reflect local perceptions. Sabyinyo translates as ‘old man’s teeth’ in reference to the jagged rim of what is probably the most ancient and weathered of the eight volcanoes. Muhabura is ‘the guide’, and anecdotes collected by the first Europeans to visit the area suggest that its perfect cone, topped today by a small crater lake, still glowed at night as recently as the early 19th century. Gahinga is variously translated as meaning ‘pile of stones’ or ‘the hoe’, the former a reference to its relatively small size, the latter to the breach on its flank. Of the other volcanoes that lie partially within Rwanda, Karisimbi – which occasionally sports a small cap of snow, most often in the rainy season – is named for the colour of a cowry shell, while Bisoke simply means watering hole, in reference to the crater lake near its peak.

The vegetation zones of the Virungas correspond closely to those of other large East African mountains, although much of the Afro-montane forest below the 2,500m contour has been sacrificed to cultivation. Moist broad-leaved semideciduous forest dominates up until the 2,800m contour, while the slopes at altitudes of 2,800–3,200m, where an average annual rainfall of 2,000mm is typical, support bamboo forest interspersed with stands of tall hagenia woodland. At higher altitudes, the cover of Afro-alpine moorland, grassland and marsh is studded with giant lobelia, senecios and other outsized plants similar to those found on Kilimanjaro and the Ruwenzori. Above 3,600m, biodiversity levels are very low and the dominant vegetation consists of a fragile community of grasses, mosses and lichens. A total of 1,265 plant species identified across the range to date includes at least 120 that are endemic to the Albertine Rift.

The most famous denizen of the Virungas is the mountain gorilla, which inhabits all six of the extinct or dormant volcanoes, but not – for obvious reasons – the more active ones. The Virungas also form the main stronghold for the endangered golden monkey, possibly the last one aside from the Gishwati Forest, which today covers less than 1% of its original extent but has recently been declared a national park. Estimates based on dung surveys tentatively place the buffalo population at close to 1,000, while the total number of elephants might be anything from 20 to 100. Other typical highland forest species include yellow-backed duiker, bushbuck and giant forest hog. The mountains’ avifauna is comparatively poorly known, as evidenced by sightings of 36 previously unrecorded species during a cross-border biodiversity study undertaken in early 2004, bringing the total checklist for the Virungas to 294, including 20 Albertine Rift Endemics.

Still in their geological infancy, none of the Virunga Mountains is more than two million years old and two of the cones remain highly active – indeed, they are together responsible for nearly 40% of documented eruptions in Africa. The most dramatic volcanic explosion of historical times was the 1977 eruption of the 3,465m Mount Nyiragongo in the DRC, about 20km north of the Lake Kivu port of Goma. During this eruption, a lava lake that had formed in the volcano’s main crater back in 1894 drained in less than 1 hour, emitting streams of molten lava that flowed at a rate of up to 60km per hour, killing an estimated 2,000 people and terminating only 500m from Goma airport.

In 1994, a new lake of lava started to accumulate within the main crater of Nyiragongo, leading to another highly destructive eruption on 17 January 2002. Lava flowed down the southern and eastern flanks of the volcano into Goma itself, killing at least 50 people. Goma was evacuated, and an estimated 450,000 people crossed into the nearby Rwandan towns of Rubavu and Musanze for temporary refuge. Three days later, when the first evacuees returned, it transpired that about a quarter of the town – including large parts of the commercial and residential centre – had been engulfed by the lava, leaving 12,000 families homeless. The lava lake in Nyiragongo’s crater remains active, with a diameter of around 50m, and, although there has been no subsequent eruption, the crater rim still glows menacingly above the nocturnal skyline of Rubavu, and a new lava lake has started to form about 250m below the level of the 1994 one.

Only 15km northwest of Nyiragongo stands the 3,058m Mount Nyamuragira, which also erupted in January 2002. Nyamuragira vies with Ol Doinyo Lengai in Tanzania as probably the most active volcano on the African mainland, with more than 40 eruptions recorded since 1882. Only the 1912–13 incidence resulted in any known direct fatalities, though 17 people were killed and several pregnancies terminated as a result of ash-contaminated drinking water in the 2000 eruption. Nyamuragira most recently blew its top in January 2010 and November 2011, spewing lava hundreds of metres into the air, along with plumes of ash and sulphur dioxide that destroyed large tracts of cultivated land and forest.

It is perhaps worth noting that these temperamental Congolese volcanoes pose no threat to visitors to the mountain gorillas, as the relevant cones are all dormant or extinct. That might change one day: there is a tradition among the Bafumbira people that the fiery spirits inhabiting the crater of Nyamuragira will reventually relocate to Muhabura, reducing both the mountain and its surrounds to ash. Another Bafumbira custom has it that the crater lake atop Mount Muhabura is inhabited by a powerful snake spirit called Indyoka, which lives on a bed of gold and need only raise its head to bring rain to the surrounding countryside.

For more on the Virungas and Rwanda, discover our comprehensive guide: