Feature image: brown pelican, Texas

Birds have enthralled me since I was a toddler. As a photographer, I’ve come to realise that understanding them – how they move, where they perch, when they are most active and so on – is at least as important as understanding your camera. The following selection of images illustrates a few lessons I’ve learned over the years.

Birds sitting still

Taking a simple portrait of a bird is harder than you might imagine. Birds seldom sit still. Even perched, their constant tiny movements can be enough to blur your picture. And among foliage, especially, shadows or background detail often break up their form. It’s easy to miss these disruptions when peering through the viewfinder, but they leap out once you get the image on your screen.

For an effective portrait, aim to frame your bird in the open, making sure to keep its head clear, but keeping some colour behind to avoid silhouetting. And try to get the light directly upon it (ie: with the light behind you). More light allows a faster shutter speed, to avoid motion blur, plus a wider aperture and thus a shallower depth of field, which helps soften distracting detail in front or behind.

Direct light also puts a glint in your bird’s eye, which can make the difference between it looking alive or stuffed. Low light is better for colours – overhead light can overexpose the upperparts and cast underparts into shadow – so shooting towards the start or end of the day often works best.

I captured this dunlin on a summer evening in northwest Scotland. It was one of a small flock drawn to a freshwater stream trickling across the beach. Once I realised what they were up to, I could plan my position. I settled down on a rock, with the stream in front and the sun behind me, and kept low. This individual approached to within a few metres. The low angle allows us into its world as it takes a brief breather, creating a sense of intimacy. The evening light brings life to the eye and colour to the background, and illuminates the exquisite plumage details of a bird often dismissed as just another ‘little brown job’.

The wire-tailed swallow was taken from a boat in the Luangwa Valley, Zambia. Boats offer great wildlife photography opportunities, especially if you allow the current to carry you quietly towards your subject. Generally, you have to be quick – if you don’t find the shot on your first pass, you may not get a second – so it pays to keep scanning ahead and anticipating opportunities. This shot is very static, but I like how the bird’s position on the tip of the branch emphasises its attenuated elegance. It also illustrates how a shallow depth of field, achieved by shooting through a long lens at a high aperture, eliminates background clutter – in this case, the tangled roots of a river bank – to achieve a ‘clean’ image.

Seconds after this shot, the swallow darted off after some flying insect. But as we continued downstream, it was soon back on the same stick. Swallows are among various fast-moving, insect-eating birds (others include flycatchers and bee-eaters) that habitually return to the same perch. They are hard to capture when dashing around but by identifying this perch, and being patient, you can improve your chances. While they’re on the move, you have a chance to discreetly reposition yourself for the optimum angle and lighting.

The rufous motmot was taken in the rainforests of Panama. Rainforests present real challenges, with the interplay of light and shadow breaking up the subject, and foreground foliage often snagging your autofocus. (Tip: use the spot focus setting and aim for the bird’s face – or, if tricky, try manual focus.) Motmots often call for ages from a favourite perch, so I was able to track this one down.

This is a backlit image – which, I’m aware, contradicts my advice about keeping the light on your subject. Backlighting can produce a pleasing halo effect, though overuse can turn this towards cliché. Here, I like it: partly because the gilding of the bird’s contours accentuates its striking shape, especially that amazing tail; and partly because that spotlight effect is so evocative of forests, in which a random beam often illuminates something you’d otherwise overlook. I took this shot early, before the sun overhead produced too much contrast. In these sombre conditions, raising your ISO setting enhances colour – though too high gives you a ‘noisy’ (grainy) image. Try shooting on several different settings then decide later which one worked best

Birds being busy

Portraits can be beautiful but it’s often more rewarding to show birds actually doing something, especially given their amazing range of talents. In this respect, understanding how birds behave – and thus anticipating what they might do – can be just as important as understanding how your camera works. And if you don’t know much about birds, you can learn a lot through patient observation. Successful images often come down to sitting quietly, watching and waiting.

This red-billed oxpecker was taken in Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park. These birds spend much of their lives clambering around their hosts, foraging for ticks, and are often so preoccupied that you have time to capture interesting shots. Here, the sharp focus on the bird’s face turns the giraffe’s mane into a kind of savannah; mammal as habitat, if you like.

Like many seabirds, Australasian gannets nest in large, noisy colonies. I took this picture on New Zealand’s North Island. Confronted with a melee of birds, the temptation can be to point and shoot, assuming that you’re bound to capture something good. Often this ends in disappointment, so instead try choosing a target and composing a picture in your mind (and view-finder). Here, I chose one amorous pair performing their bill-fencing display. A tight focus on this pair emphasises their individuality among the throng.

Birds’ breeding behaviour is endlessly fascinating. The golden-backed weaver was busy building its nest in Uganda’s Queen Elizabeth National Park. Here it posed perfectly, as though showing off its architectural skills.

Birds flying about

Rapid exposure helps with birds in flight. Birds’ wings beat very fast and it is tricky to tell through your viewfinder what exactly they are doing – whether, for instance, they are obscuring the bird’s face or casting unwelcome shadows across its body. Take a rapid burst of shots and you’re more likely to get one that works. Where possible, focus on the face. Having the birds flying into your picture creates a sense of expectation and thus a more successful image than birds flying out of it. (Arrival, in life, is invariably more exciting than departure.)

This female ruby-throated hummingbird was taken in New Brunswick, Canada, and presented the challenge of capturing a bird whose wings beat at 50 times per second. It was following a regular circuit between flowers in the garden of my chalet, so I had time to get into position. Hummingbirds often hover stationary for a second or two before moving forward to the flower. This is your chance. Here I used a very fast shutter speed, though not so fast that the wings are pin-sharp – which is fine, as the blurred tips conveys the breathtaking speed. The key thing here is the focus on the face.

A good way to catch a bird in flight is at take-off or landing. The great egret was arriving at its nesting colony in the Iberá Wetlands, Argentina. Birds were coming and going constantly so I had plenty of time to think about the shot. I like the brutal sharpness of bill and claws against those otherwise angelic snow-white wings.

The greylag geese were in a field on the Scottish coast. They had been taking off in small, regular parties, so I knew the direction the next group would take and was able to find a good position, with that lovely west coast evening light behind me. I like how each bird is in a different position, with wings at a different point of the up- or down-stroke, and how their straining necks express the sheer muscular effort of take-off. I also like the line of treetops, which keeps a connection with the land. Note the light in the eyes.

The bigger picture / getting arty

Backgrounds often create the most exciting avian images. Not only do they convey a sense of place, they also illuminate the bird’s story, opening a window on to the world for which it is so beautifully evolved, and which it can evoke so powerfully. Success comes down to composition – critically, where do you place the bird? Keeping it off-centre is often effective, allowing its backdrop to breathe. Look for diagonals that lead the eye.

The beauty of birds also lends itself to pure aesthetics. Beyond merely capturing a bird or its environment, you may find more abstract images in form, colour or movement. Success in this respect is often serendipitous: pleasing patterns spotted on your screen, after you’ve downloaded your snaps. But keep an open mind when peering through that viewfinder. Look for details, textures and shapes that might have a visual impact independently of the bird.

The keel-billed toucan is heralding daybreak over the forest canopy of Chiquibul National Park, Belize, flaunting its outrageous bill as first light burns off the mist. The image is a bit noisy (the dawn darkness had me overdoing the ISO) but the composition is pleasing.

This image of common eider from Iceland illustrates how water offers boundless artistic possibilities: the reflection of a boat’s yellow hull frame its subject in liquid gold.

By contrast, the gentoo penguin, captured from the deck of my ship in Antarctica, is swimming below the surface. It appears preserved in aspic, with the play of light above suggesting milky swirls in a cup of coffee.

Finally, if in doubt, try black-and white. If the light is too poor for colour, the tonal subtleties of monochrome can draw attention to texture, as in this eastern screech owl poking its head from its palm stump nest hole in Texas. And the beauty of digital is that you needn’t decide this in advance. One click on the keyboard and hey presto, instant art!

More information

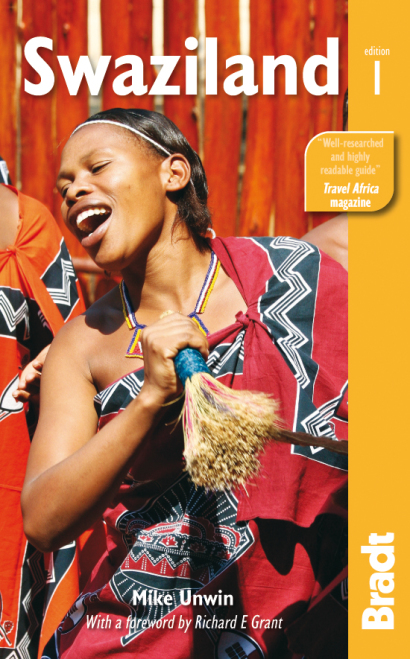

Mike Unwin is the author of several books for Bradt, including Swaziland and Southern African Wildlife, plus some 35 other books for both adults and children. A multi award-winning wildlife and travel journalist, he was voted UK Travel Writer of the Year 2013 by the British Guild of Travel Writers. Mike lived and worked for eight years in southern Africa, and has travelled to every continent to find, photograph and write about wildlife. Today he lives beside the seaside in Brighton, UK.