Written by Bradt Travel Guides

Although it is known by the name Artsakh to its inhabitants and to many Armenians, the more widely known name Nagorno Karabagh dates from the Khanate of Karabagh’s formal entry to the Russian Empire in 1813, nagorno being Russian for ‘mountainous’ and karabagh Turkish for ‘black garden’. Today Nagorno Karabagh is very predominantly inhabited by ethnic Armenians – according to a census of 2015 they make up 99.7% of the population. The language in the streets of its towns is Armenian – albeit a strikingly different dialect thereof – and the currency in use is Armenian. However, it is not part of Armenia: it has its own president and a government with its own foreign ministry, its own flag, its own stamps and its own national anthem. Despite all this, its existence as a sovereign state is unrecognised by any UN member state (including Armenia) and no foreign government can provide consular services there; de jure it is internationally considered part of Azerbaijan, yet in reality it can only be entered from Armenia.

Why go? One answer is that it has some magnificent scenery – it isn’t called Nagorno for nothing. Even within the pre-1994 boundaries the land rose to 2,725m at Mount Kirs; the incorporation of territory that formerly separated Nagorno Karabagh from Armenia means that the highest point is now the 3,584m summit of Mount Tsghuk, which falls on the border with Armenia in Syunik province. It also has some very fine monasteries, and some thought-provoking damaged buildings and streets from which the ethnic Azeri population has fled. If you’re planning a visit, these are the things you shouldn’t miss.

Stepanakert

Formerly Khankendi, the capital of Nagorno Karabagh was renamed Stepanakert in 1923 in honour of the Armenian Bolshevik Stepan Shahumyan (1878–1918) after whom Stepanavan is also named. His statue stands in Shahumyan Square at the northern end of Vazgen Sargsyan Street, one of the main shopping streets. The town suffered considerable damage in the war but this has now been repaired and the bustling town centre has the feel and appearance of a capital city, albeit a small one.

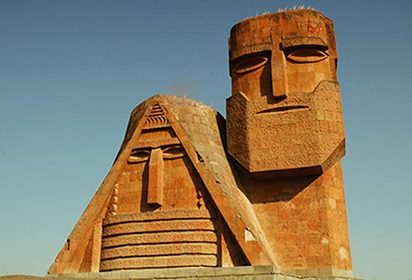

The town centre has various architectural treasures and museums worth visiting, but one sight of particular note is located on a small hill on the north side of Stepanakert: a statue reproduced in a thousand Karabagh souvenirs. Created by the sculptor Sargis Baghdasaryan in Soviet times, it is officially called We Are Our Mountains, though it is usually referred to as Tatik yev Papik (sometimes ‘Mamik yev Papik’, Granny and Grandad). Portraying an elderly couple in national costume, the statue is intended to symbolise the unity of the Karabagh people with their mountains. While it is a couple of kilometres from the city centre, a good pavement leads all the way there and refreshments are on sale at the foot of the hill.

Shushi

The important historical centre of regional culture and the former capital of the Karabagh khanate, known to its present Armenian residents as Shushi and to Azeris as Shusha, is visible from Stepanakert on its dominating hilltop position to the south, set on a precipice overlooking the impressive gorge of the Karkar. It is notable for its distinctive 18th- to 19th-century architecture. Unlike Stepanakert the scars of conflict are still very evident in Shushi, with many ruined buildings, but the reconstruction efforts of recent years are also obvious. Prior to 1988 the town was one of the few in the region to have a mixed and relatively well-integrated Armenian and Azeri population. Now the Azeri population has fled while the Armenians remain. Some of the blocks of flats are still burnt-out shells while others have been fully rebuilt, and more and more of the older houses and buildings are being restored in their original historical style, lending the town an increasingly cultured feel and making for pleasant urban walking. Something of the complexity of emotions surrounding Shushi is perhaps captured in the language used today to refer to the battle of 8–9 May 1992 in which the town fell to Armenian forces, with Armenia celebrating the town’s ‘liberation’ and Azerbaijan lamenting its ‘occupation’.

Dadivank

Dadivank isn’t just one of the finest monasteries in Nagorno Karabagh, but in Armenia in general. One of the largest medieval complexes in the region, it is traditionally believed to be on the site of the grave of St Thaddeus who was martyred in the 1st century for preaching Christianity, ‘Dadi’ being a phonetic transposition of his name. The layout is exceedingly complex and there are buildings on two levels. The 9th-century church of St Thaddeus, built over his grave, is at the north side of the complex. To its west lies a chapel resembling a gavit, said to be the burial vault of a princely dynasty, built in 1224. On the lower level are the kitchen, refectory and wine press, as well as various accommodation quarters. The building with four round pillars on square bases is, according to an inscription of 1211, the temple.

Tigranakert

Said to have been founded by Tigran the Great, this ancient city is centre by an imposing fortress. Behind the medieval castle a wavelike escarpment on the southeastern slope of Mount Vankasar (879m) rises from the plain. The triangular fortified city, with the citadel at its apex, occupies the lower third of the slope above the castle. The site covers some 50ha and excavations, started in 2005, are continuing. Already two of the main walls of the city have been uncovered. Built of local white limestone, without mortar, the stone blocks were dovetailed together by means of triangular joints. Also notable are the steps carved into the rock on the edge of the escarpment. The many finds, dating from the 5th century BC to the 17th century AD, are now displayed in the museum that opened in the medieval fortress in June 2010.

Gandzasar Monastery

Dedicated to John the Baptist, Gandzasar’s name derives from the presence of silver deposits in the area and it has been fully restored since 1991. It is particularly notable for its exquisite carved detail. Surrounded by walls, it is a cross-dome church with its 16-sided tambour topped by an umbrella cupola. The tambour of the church is an outstanding work of art, decorated with numerous sculptured images between the triple columns separating each side. The gavit has an immense west portal which shows two birds as well as much varied abstract design. Over the north door are two lions, emblems of the Hasan-Jalalian family. The six-pointed star in front of the right-hand creature is associated with Armenian royalty. The gavit is surmounted by a belfry supported by six columns. The interiors of both church and gavit have yet more carving including the finely carved front of the altar dais, the pattern of each triangle or square being different.

Jhingalov hats

Food and drink in Nagorno Karabagh is similar to that in Armenia, but one local speciality is herb bread, known as jhingalov hats. This is a classic flatbread into which are incorporated anywhere between seven and 15 seasonal wild herbs and vegetables. The dough is rolled out into a flat sheet, a generous pile of chopped greens is placed on top, the sides of the dough are folded over and the whole is rolled out again. It is then cooked on a griddle brushed with oil. It’s absolutely delicious when fresh, though beware of some inferior imitations. You can watch it being made at the market in Stepanakert and buy it fresh and warm straight off the hotplate. Jhingalov hats makes excellent picnic food.

Discover more about Armenia and Nagorno Karabagh in our comprehensive guide: