Outside my window, the South Atlantic lay unbroken; an azure expanse of ocean below and sky above. Some 3 hours after passing the Namibian coast, a lone patch of clouds appeared on the horizon. As we approached, I could just discern patches of green peering through.

Atop a narrow ridge, a tiny strip of runway appeared, the sheer drops at each end plummeting into the sea. The necessity of our re-fueling stop in Windhoek became apparent; if landing conditions weren’t favourable, we would have to return there. There simply wasn’t anywhere else to go.

A lone outpost in the South Atlantic between southern Africa and South America, St Helena is the epitome of isolation. Only 16km long and just under 10km wide, the island was discovered by the Portuguese in the 15th century, but remained uninhabited until the arrival of the British. Today, it is Britain’s second-oldest territory after Bermuda.

For centuries, the only way to arrive was by sea. In recent years, the RMS St Helena made the five-day journey from Cape Town every three weeks and was the island’s sole connection to the outside world. That all changed in November 2017, however, with the opening of the airport. Although finished in 2016, it was not suitable for commercial aircraft for another year as planes were unable to land due to excessive wind shear. Today, a once-lengthy sea voyage has been reduced to a 6-hour journey from Johannesburg.

Friends Raf and Cisca Jah from the UK-based African and Oriental Travel Company were the first to bring a scuba-diving tour group to the island by plane, and their report was enthusiastic. They insisted I come with them on their next excursion, but I wasn’t initially enthusiastic; the trip would be long and expensive, and what was there to see on an island so small?

Then again, past experiences have taught me that it is the unexpected places that always prove to be the best surprises. Five months later, I met up with Raf, Cisca and two other divers in Johannesburg for a journey to the most remote place I’d ever been.

Arrival on the island

I must admit the flight filled me with trepidation. Before departing, I read an article that claimed it to be the most terrifying landing the author had ever experienced.

During the re-fueling stop at Windhoek, Cisca showed me an app on her phone entitled ‘St Helena Airport’, where the player attempts to land a plane on a 3D graphic representation of the island. Based on her success record, I was grateful she wasn’t piloting our aircraft. Happily, our arrival was smooth with nary a bump; indeed, the bus ride between the terminal and the plane at Johannesburg airport was more nerve-wracking.

Right away, the island’s laissez-faire attitude became apparent. Despite the fact we were the only flight for three days and there were just 75 passengers, it took a full hour to clear immigration and retrieve our luggage, and the resulting queue was somewhat baffling. Then again, as the staff work for only a few hours twice a week, I assumed they wanted to make the most of it!

Luggage retrieved, we ventured outside to find our transport waiting. On hand was Matt Joshua, manager of the Mantis Hotel, and Anthony Thomas, owner of Sub-Tropic Adventures. Outside the airport the landscape was rugged and rock-strewn, but as the road ascended, barren quickly transformed to verdant. Reaching a ridge top, the tiny capital, Jamestown, loomed below, wedged between the ocean and steep cliffs. It felt like we had arrived on another island.

We soon checked in at the Mantis, our home for the following week. The island’s most upscale accommodation, it occupies a row of former officers’ quarters dating from the 18th century. The elegantly appointed rooms featured a rare commodity on St Helena: free and reliable Wi-Fi.

Exploring Jamestown

With the afternoon free, I grabbed my camera and set out for a ramble around the island’s only major settlement, home to around 700 people.

Founded by the British East India Company in 1659, Jamestown is steeped in history and houses one of the finest collections of Georgian architecture in the world, with many buildings constructed from the local volcanic rock. Each one has its own story; across from the Mantis, New Porteous House hosted the Duke of Wellington, while just down the road, the century-old Consulate Hotel features a life-sized figure of Napoleon on the upper terrace.

Scott at the top of Jacob’s Ladder An aerial view over Jamestown The old post office Main Street

The main aim of my wander was to the town’s most iconic landmark, cut into the side of the rock. As staircases go, Jacob’s Ladder is seriously epic. Constructed in 1829, the 699-step staircase links the capital with Ladder Hill Fort above. An incline railway once existed here too, but termite damage prompted its dismantlement in 1871. For those adverse to heights, merely looking up the vertiginous ascent is enough to induce vertigo. For the intrepid able to conquer it, a certificate is available at the museum. ‘Not today’, I mumbled to myself.

On my way back to the Mantis I stopped off for some refreshment at the St Helena Coffee Shop. Grown at only two plantations locally, the coffee is excellent and among the world’s most expensive. Bags are available at the shop for £15, but can fetch £90 at Harrods in London.

While enjoying my cuppa, I reflected on the town’s definite vibe. Something felt different, but I initially couldn’t determine what. Then it struck me: passersby said hello, their faces not buried in personal electronic devices. TV screens didn’t bombard me with 24-hour news and golden arches were absent. It was slower, gentler; reminiscent of when I grew up. Before I knew it, I had been won over.

Venturing to the waterfront, I passed the old Customs House en route to the main wharf. Opposite some old warehouses, a sweep of shipping containers lined the roadway. Above, the vertiginous cliffs were encased in swathes of netting to prevent rockfalls. I soon found Sub-Tropic Adventures and beyond that, our embarkation point for the next day’s diving. It was going to be a long walk with my underwater camera gear.

Island language and heritage

Although English is the official language, it’s not immediately apparent! The local dialect, called ‘Saint’, utilises English words in decidedly unusual ways, such as in the phrases ‘What you name is?’ (What is your name) and ‘Us goin town’ (We are going to town).

One friend likened to it a cross between Cornwall and Australia, but to my ears it sounded like a mélange of Kiwi, Australian and English. The locals tone it down for the tourists, but once they start conversing in full-on patois, subtitles are required. I overheard a conversation between the girls at the coffee shop and couldn’t decipher a word.

And yes, the inhabitants really do call themselves Saints. Over the centuries, various nationalities and cultures phave passed through, leaving a conspicuous imprint on the island’s population. I asked Anthony how long his family had been here.‘We’ve been here for 200 years’, he said. ‘We have some African, but mostly we are a mixture of Portuguese and Chinese.’ DNA testing would no doubt reveal some extraordinary results.

Diving excursions

Isolated islands are magnets for undersea life and St Helena is no exception. Bolstered by a mixture of warm and cool currents, the diverse marine fauna features both western and eastern Atlantic and circumtropical species.

Plunging in revealed an environment I hadn’t encountered before. Dramatic seascapes echoed the craggy terrain above, with huge boulders and sheer rock faces riddled with caves, archways and overhangs. The visibility was exceptional, at times approaching nearly 50m, no doubt due to the lack of sediment from runoff. The water temperature was a comfortable 25°C.

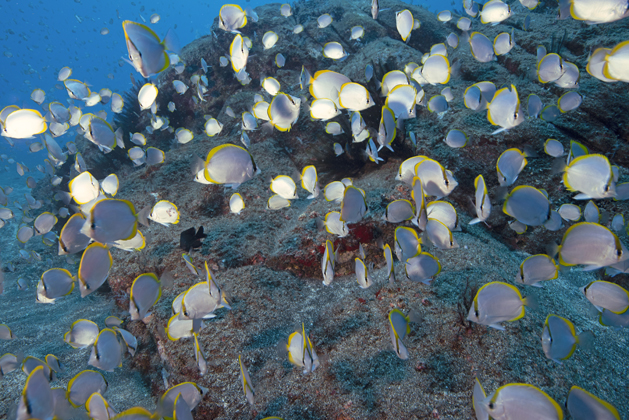

Although reef-building corals were absent, an abundance of tunicates, algae and sponges encrusted the rock faces. Endemic orange cup corals added a splash of colour along with harpoon weed (a red algae), tiny anemones and various species of hydroids. What was really astounding was the fish life. Due to long-term isolation, the island is home to a variety of endemic species. Most prolific was the St Helena butterflyfish, whose numbers were simply astonishing. Schools were so dense, divers could virtually disappear within them.

More elusive were hedgehog butterflyfish, distinctively patterned with a chocolate brown head and lower half and white on top. Mixed schools of sergeant-majors and ocean surgeonfish foraged the reef, while yellow goatfish patrolled the bottom. Nocturnal hunters, squirrelfish and blackbar soldierfish congregated in large schools under ledges and overhangs during the daylight hours.

Other notable endemics included strigate parrotfish, island hogfish, St Helena white seabream, flameback angelfish, Helena wrasse and St Helena damselfish. Joining them were more familiar faces, including moray eels, amalco jacks and Chilean devil ray, smaller cousins of the manta. We spent the week exploring the area’s excellent dive sites, including a number of wrecks. Best of all, we had every dive site all to ourselves.

Island history

Although I had come for the diving, the island’s topside attractions proved equally enticing. Another afternoon, I took a short tour with Wayne Crowie, who had driven us from the airport on the first day.

Our first destination was High Knoll Fort, dating from 1874 and largest of the island’s military installations. From town, it appears Jacob’s Ladder is the highest point, but the road ascended further to the fort’s lofty perch at 584m. The view from the eroding ramparts commanded spectacular vistas over the island; a miniature continent of mountains, forest, farmland and semi-desert.

High Knoll Fort Plantation House

Our final stop was Plantation House, the Governor’s official residence. Nestled among forested grounds, the stately building was erected in 1792 by the East India Company. It is also home to the island’s most-famous resident: Johnathon the tortoise. At 188 years old, he is believed to be the planet’s oldest living creature and shares his outdoor compound with several other tortoises. His advanced years don’t stop him from chasing the females. Well, chasing might be something of an exaggeration …

With visiting hours over, I had to settle for a walk along a fenced pathway. I could just discern Johnathon hiding under a cluster of low trees. Overhead, white birds wheeled in abundance and I asked Wayne what they were. ‘White birds,’ he replied. That really is their local name, but in actuality they are fairy terns. The island’s early residents weren’t especially creative in the naming department.

During the week, I spoke to some residents about life on the island and the responses were as varied as their genetic makeup. A referendum was held on whether to build the airport but the decision to go ahead was by no means a landslide win, as many were content with the RMS St Helena. Once the airport opened, tourist arrivals were promised, but they have yet to materialise, leaving many frustrated. Flights are generally full, but they only arrive twice weekly on Saturdays and Tuesdays.

Diving with whale sharks

Our journey coincided with the arrival of some very big visitors. During the summer months between November to March, whale sharks congregate around the island in large numbers. The world’s largest fish, they can reach lengths up to 14m, but these gentle giants are filter feeders, sieving plankton and small fish through mouths up to 1.5m wide.

Whale-shark excursions are done by snorkeling and encounters are limited to 45 minutes. Guidelines are strict; participants must remain 3m away from the sharks and no touching is allowed. However, as I quickly discovered, the sharks seem unaware of the rules.

Setting out from James Bay, it didn’t take long for Anthony to find one. Plunging in, I spotted the 8m-long individual swimming at the surface some 15m away. Suddenly, it made an abrupt turn and headed in my direction. It was the first time I’d ever seen a whale shark front on and I was utterly spellbound.

Photographing happily, I was unaware of how close it was. Looking up, I was startled to see it was only an arm’s length away! I frantically maneuvered to get out of its way, scraping my knee on it in the process. ‘It wasn’t my fault; I wasn’t even moving’, I protested to Anthony, who had watched the entire episode from the boat. ‘Don’t worry about it’, he said with a chuckle.

We spent the next 40 minutes with the shark, who proved to be exceedingly tolerant. If they moved away, pursuit wasn’t necessary, as they inevitably returned for another look. On a second excursion two days later, a massive 10m individual arrived that was even more curious. This time I got out of its way well in advance.

A famous exile

On our last day, we did a full-day island tour with Aaron Legg of Aaron’s Adventure Tours. Our four-wheel drive proved indispensable, as Aaron took us on some bone-rattling roads.

Despite its compact size, the island features a big history. Many famous people have visited, including Captains Cook and Bligh, Edmond Halley and Charles Darwin. However, there is one man to which the island is inexorably linked: Napoleon Bonaparte. After his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, Napoleon was exiled to St Helena, spending his final years at Longwood House where he died in 1821.

Longwood House Napoleon’s tomb

After stopping for a view of Jamestown, we set off for Napoleon’s Tomb, situated in the Sane Valley. The walk was an easy 1km-return route and the setting was quite beautiful, surrounded by gardens and shaded by tall trees. The only thing missing was Napoleon himself. He was only interred here from 1821–40, when he was exhumed and taken back to Paris for burial.

Napoleon died on 5 May 1821 and much debate surrounds the actual cause of death. Some claim the British poisoned him, but the story told at Longwood is that he succumbed to long-term exposure to toxins in the wallpaper. In 1858, the French government were granted possession of Longwood and today, along with the burial site, it remains a French property, administered by a French representative under the authority of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Around the island

Leaving the tarmac behind, we passed a sign indicating the site of a Boer internment camp. During the Boer War between 1900 and 1901, over 6,000 prisoners were held on the island. A detour to the coast revealed dramatic cliffs with stunning views of Turk’s Cap and the Barn, formations we’d seen during our diving excursions.

En route, we kept a lookout for wirebirds, the island’s national bird and sole indigenous bird species. Deadwood Plain’s open expanse is a favoured nesting area and we observed many, with several right by the roadside. From less than 200 birds in 2006, numbers have rebounded to over 500.

For our packed lunch, we stopped at the Millennium forest, once home to the Great Wood, an extensive forest of indigenous gumwood trees. With no native land mammals, the flora and fauna were soon decimated by introduced livestock, cats, rabbits and rats, with several plant and insect species becoming extinct. In 2002, the Millennium Forest project was implemented to replant part of the lost forest. Gumwood is slow-growing, so it will take time to regain its past grandeur. In the meantime, if you get lost, just stand up.

After lunch, another off-road excursion took us to a dramatic overlook of the airport and the peaks of Greater and Little Stonetop. Ground-hugging sour plum carpeted a semi-desert landscape of ochre and sienna tones, but only minutes away the landscape was dominated by New Zealand flax.

The manufacture of flax fibre generated considerable revenue for several decades, but transport costs and competition from synthetic fibres initiated its downfall. The British Post Office’s decision to use synthetic fibres for its mailbags dealt the fatal blow and the mills closed in 1965. ‘The Suez Canal and elastic bands sealed the fate of St Helena,’ said Aaron with a chuckle.

At the island’s south end, planted eucalypt forests dominated, while higher still, tree ferns shrouded Diana’s Peak, the island’s highest point at 818m. En route, we made a quick stop at Bell Rock, which really does sound like a bell when struck. Passing one of the island’s coffee plantations, we commenced our descent to the coast.

The landscape changed yet again, giving way to an arid landscape. Dominant landmarks were twin rock pillars called Lot and Lot’s Wife, named for the biblical tale of Sodom and Gomorrah. We passed a tiny Baptist church with Lot’s Wife as a backdrop and I was amused by the irony. Nearer the coast, the arid terrain featured date palms and I felt like I’d gone from Hawaii to the Middle East in a matter of minutes.

Arriving at Sandy Bay revealed a St Helena first: an actual beach, the black sand a testament to the island’s volcanic origins. At one time, a stone wall separated the shore from the valley, as it was a favoured spot for smugglers to come ashore.

Today, only a small section of wall remains. Although inviting, the rough waters are unsafe for swimming. Heading back to Jamestown, we passed the familiar sights of Plantation House and Half Tree Hollow before our zigzag descent to town. Even after 7 hours, we didn’t come close to seeing everything.

Reflecting on my visit, the island was a curious cross between a 1970’s time warp and a parallel universe. Along with all the wonderful things the island has, it is notable for the things it doesn’t have: ATMs, fast-food chain restaurants, billboards and shopping centres. Make no mistake though, this is no criticism. Quite the opposite in fact. In our madcap era of hyper-connectivity, St Helena was a wonderful breath of fresh air, proof that unexpected is indeed the most pleasant of surprises.

Despite the new air connection, St Helena remains off the beaten path, but this is a huge part of its appeal. Even in the 21st century, it is reassuring to know places still exist where the journey remains an integral part of the destination.

More information

For more information on visiting St Helena and to plan your trip, check out the African and Oriental Travel Company or our comprehensive guide.