There are two sights and smells of Lika that are permanently etched into my brain. One is fireflies. I had never seen these magical creatures before, their luminescent little bottoms casting a glow as they danced about in the dark. These tiny beauties nearly made up for the preposterous number of enormous moths that, in contrast, turned everything dark as they draped themselves on every light source.

The other is a bunch of dried herbs my aunt Bosa had hanging on my bedroom wall. Their scent was smoky, with hints of bonfire mixed with burnt sugar and a dash of something else – maybe dill or fennel. I went to sleep to that soothing scent, and woke up to it, not realising it would be many years before I discovered what it was.

Forty-one years later, I was in southern Sardinia about to have a long leisurely lunch of spit-roasted suckling pig at a hilltop agriturismo. As I walked along a rough farm track with the owner, that long-forgotten scent wafted from the verges. I stopped abruptly and gently stroked the pale yellow-headed herbs at my feet, drinking in the familiar fragrance. ‘What is this?’ I asked the owner. ‘I only know its Sardinian dialect name,’ she said as I groaned inwardly. ‘Ask my husband. He’ll know the Italian name.’

Elicriso – everlasting. The French call it immortelle. Helichrysum is the scientific name for this little yellow-headed shrub I’ve since found flowering on the Croatian islands of Lošinj, Korčula and Krk, all over Corsica and on the sand dunes of Cap Ferret on France’s wild Atlantic coast. I even found clumps of it growing in Britain along Dorset’s Studland peninsula. I surreptitiously stole a sprig from a waterside bar in Krk Town, and I now have its scent on tap in my house in Hertfordshire. The herb’s essential oil can reportedly cost up to £1,000 a litre, and it’s said to have healing and anti-ageing properties.

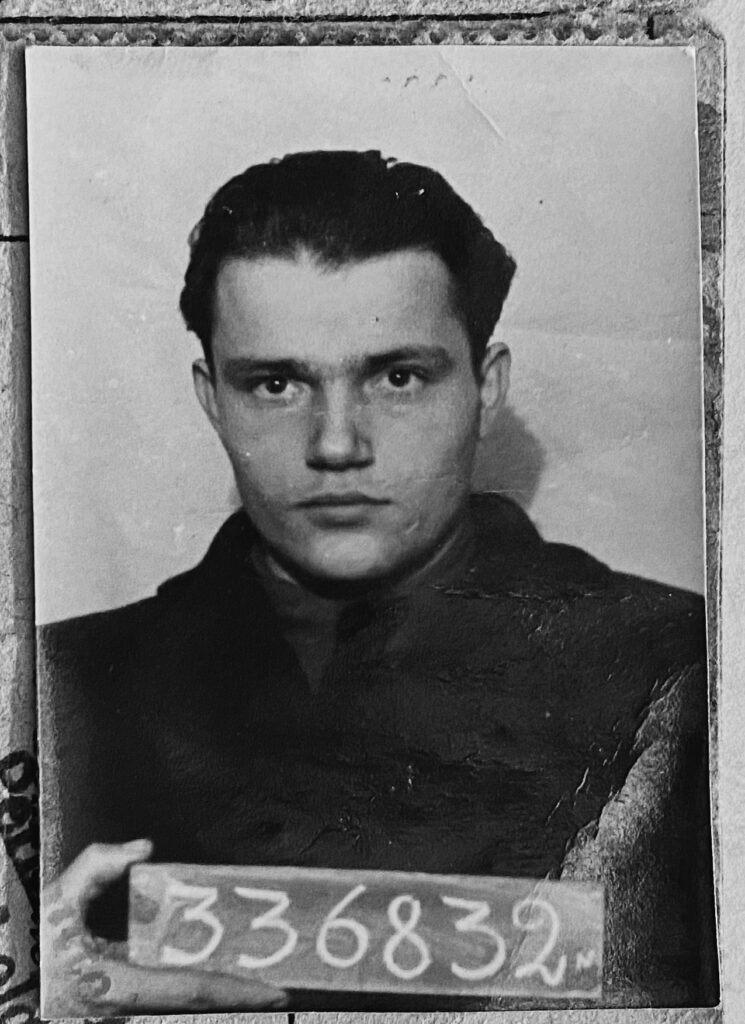

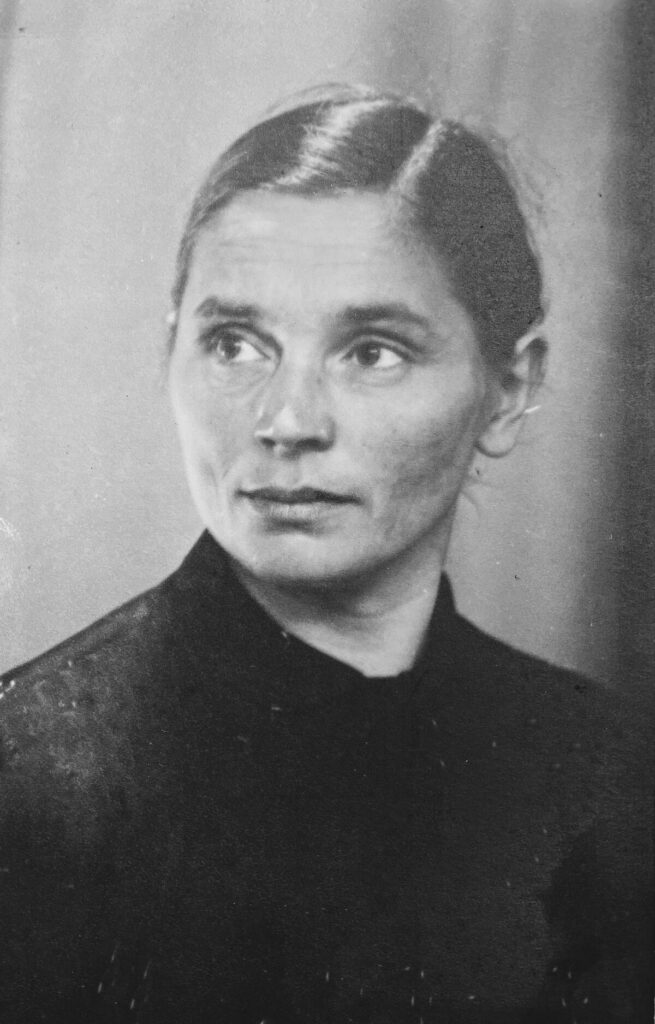

In a sweet coincidence, the Serbian word for this herb, smilje, is a form of my paternal grandmother’s name, Smilja. I never knew my father’s mother: she died in 1929. Smilja gave birth to seven children, one of whom, one-year-old Ðuro, died with her of pneumonia when their farmhouse was cut off for days in a snowstorm and no medical help could get through to save them. My father was three years old at the time. There is no one left alive who would have any memories of my grandmother Smilja, but, like her name, she lives on – at least in these pages.

After Smilja’s death, and with six children aged from one (Ðuro’s twin, Dušan) to nine, my grandfather Rade lost little time in finding another wife. Enter my step-grandmother Boja, and, not long after, a half-brother for the six siblings, my uncle Vlado. I did not know of either of these two people’s existence until one day Vlado came to the little house in Suvaja. For some reason, my father never mentioned that he had a stepmother and a half-brother.

I was in the garden playing with my now familiar gang of cousins and chums. ‘I knew at once which one of you girls was Mićo’s daughter. I could see it in your face,’ Vlado told me years later. With so many splintered family connections in our history, so many premature deaths, this little nugget brought a rush of warmth and a sense of belonging.

I never called Vlado by his real name. He was always known as Braco, which means brother. It’s a common nickname for Serbian boys and men. Its feminine form, Seka – sister – is just as common. It is, in fact, my nickname.

Vast swathes of my family know me only as Seka, and not the name I was christened with – Marija – which I use when I’m travelling in the region. My anglicised name, Mary, sounds strange to Slavic ears, and is usually pronounced as Meddy (which, I have to admit, makes me shudder a little). When I appear in local newspapers in Croatia and Serbia, my name is often spelled phonetically, so I then become Meri Novaković – another unfamiliarity. All these names for all these sides of me.

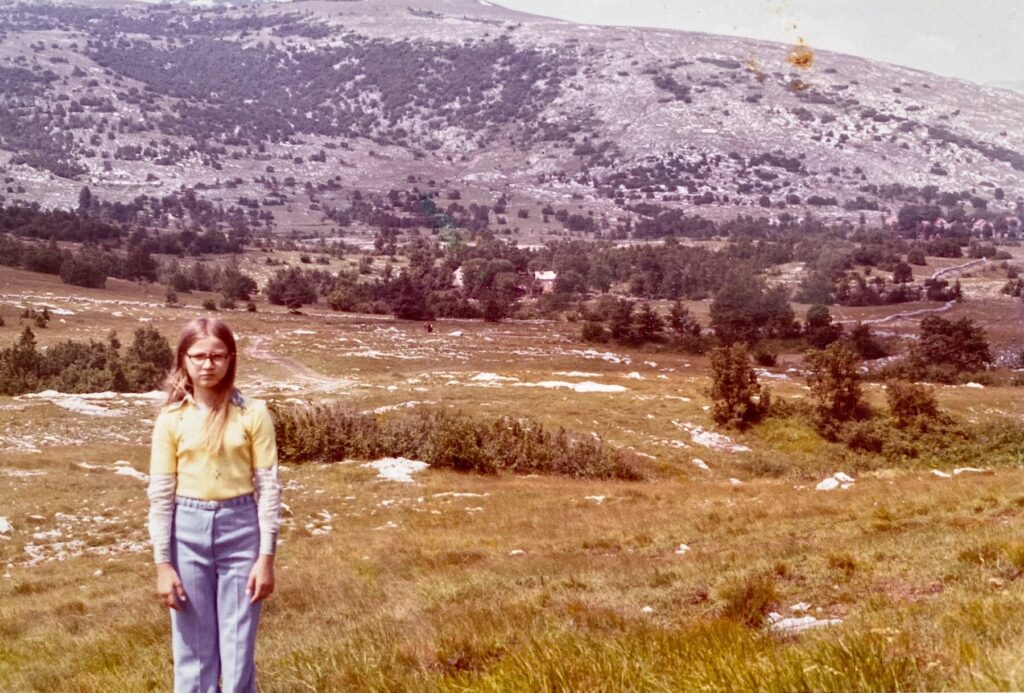

My uncle Braco (aka Vlado) had come to Suvaja to take me to my father’s region, which is around the village of Velika Popina, about twenty-five kilometres to the south. The road leading to it has the sort of hairpin turns that are a rally driver’s dream, but to me, when I drove it many years later as an adult, it was more of a nightmare. It also takes you through what feels like a continental divide: gone are the lush, thick forests and, in their place, wide expanses of scrub-covered mountains with sparse vegetation poking through the limestone landscape.

I was in the Dinaric Alps, the rugged mountain range that swoops from Slovenia through Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Kosovo, Montenegro and finally into Albania. It is here where a certain wildness takes over, a stark beauty in this karst land. You see it in the Velebit mountains just to the north, and in the Biokovo range that looms over the Adriatic resort of Makarska. The people of the Dinaric Alps are said to be the tallest in the world. My father was six feet tall despite growing up in grim poverty, when a poor diet would have stunted his growth.

This is when my memories turn into a jigsaw puzzle with a few of the pieces missing, but some things stand out. While we walked along the karst plain, with those austere mountains rising behind us, a group of strangers who turned out to be some of my closest relations suddenly surrounded me. My father’s eldest sister came to meet me. Sofija would have been fifty-eight then, only slightly older than the age I am now, but dressed, as everyone in Lika her age seemed to be, in a frumpy frock, thick cardigan and heavy stockings, her curly grey hair poking out from under her headscarf. She was with her son Jovo and his two children, Aleksandra, about my age, and her younger brother, Bato.

Then I was introduced to my step-grandmother Boja, aged seventy-seven and dressed in full traditional Balkan black and brown. I found it amusing that both she and my mother’s mother were called Boja – usually prefaced with the Serbian word for grandma: baba. So I had not one but two Baba Bojas, and I was delighted as I hugged and kissed my new family. It was the one and only time I was to see any of them.

More information

To read the full tale of Mary’s life and travels in Croatia’s hinterland, check out her book: