Lovers of architecture will already be aware of Georgia’s monasteries. Whether it’s a 6th-century cave complex or a delicate 12th-century church, their elegant exteriors stand in perfect harmony with their surroundings. What’s more, their compact build belies ornate interiors, with walls and ceilings adorned with well-preserved frescoes and religious icons.

So to help you plan your ideal itinerary that takes in the very best of Georgia, here is my selection of the country’s finest monasteries. Each is well worth your exploration.

Gelati Monastery

Set in the hills 10km to the north of Kutaisi, the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Gelati Monastery is one of the most beautiful spots in Georgia. The centrepiece is the great Cathedral of the Virgin, built by King David the Builder in 1106–25 (though in a style typical of the 11th century). Burnt by the Turks in 1510, and again by the Lesghians (from the north Caucasus) in 1579, it was restored, then closed under communism, and reopened in 1988.

The interior is full of light, and painted, mostly in the second half of the 16th century, in fantastic colours (although a blue background is unusual in Georgian churches). However, the pride of the church is a remarkable mosaic (containing 2.5 million stones) in the apse of the Virgin and Child with the archangels Michael and Gabriel.

Created c.1130 in a Byzantine style with specifically Georgian features, it was damaged by earthquakes later in the same century and subsequently. The lower half was restored by painting – although this is often denounced as communist vandalism, it seems that it was genuinely impossible to restore it as mosaic. The mosaics were then badly damaged by rain at the end of 2016 and the US embassy is apparently funding their restoration – now the metal roof has been replaced with turquoise-glazed ceramic barrel tiles.

Motsameta Monastery

Slightly closer to Kutaisi is Motsameta Monastery. It’s smaller and quieter than Gelati, although its cliff-edge setting is more spectacular by far. It commemorates the brothers David and Constantine Mkheidze, killed by Arabs in the AD720s for refusing to convert to Islam and then thrown into the gorge here. They are now saints, with their skulls in a casket behind the red velvet curtain, and your wish will be granted if you crawl three times under their tomb, set on two lions on the south side of the church, without touching it.

The monastery was founded in the 8th century, but the present church and bell-tower were built by Bagrat III in the 11th century; the frescoes were destroyed by the Bolsheviks. It’s busy but feels much less like a tourist site than Gelati. To the left of the gatehouse is a steep path down to the river, which makes this a very popular excursion in summer, when Kutaisi swelters.

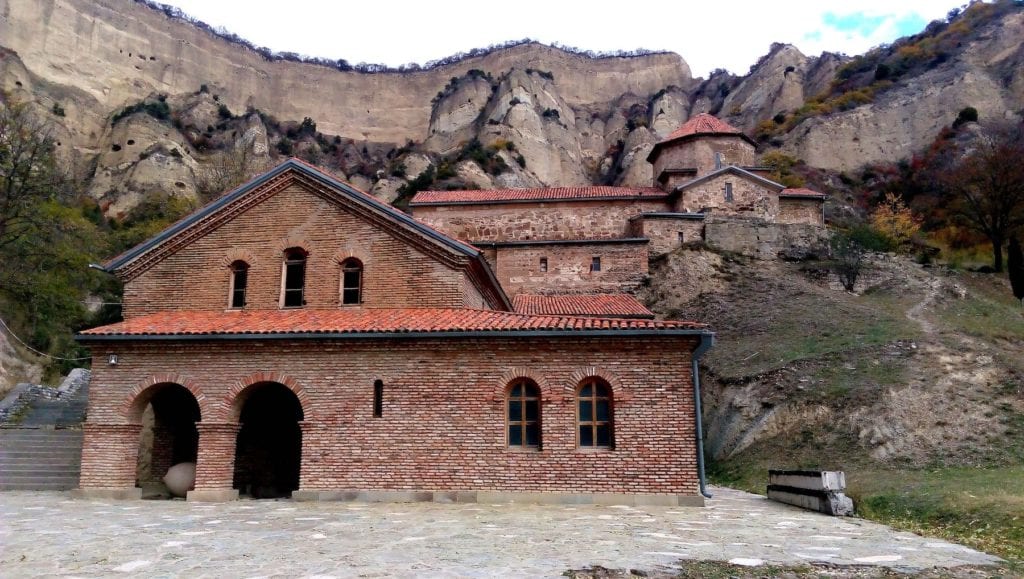

Shio-mghvime Monastery

In the hills 12km west of Mtskheta, the monastery of Shio-mghvime is built in a limestone canyon in a spectacularly picturesque manner, though the buildings look more like a farm than a monastery; it was founded in the 6th century by the Assyrian monk Shio Mgvimeli, another of the 13 Assyrian Fathers, who voluntarily spent his last 20 years in a cave.

A simple cruciform church was built over his grave in 560–80, as well as the Monastery of the Virgin, built on a nearby hilltop by Davit Agmashenebelis in 1103–23 (and restored in 1678), a 12th-century refectory, and a 7km aqueduct at the end of the same century.

Zedazeni Monastery

In the heart of the Saguramo Nature Reserve sits the monastery of Zedazeni. It was founded by Ioane Zedazneli (St John of Zedazeni), one of the Assyrian fathers, who lived here in a cave from AD501 to 531, attracting many fellow hermits; the Church of St John the Baptist was built over his tomb, just south of the cave, in the 7th–8th centuries and has a 7th-century fresco of St George and the Dragon.

Ioane’s disciple founded Kvemo (Lower) Zedazeni at the foot of the mountain, and a three-nave basilica (with an unusual rectangular sanctuary) was built in the AD860s and 870s; now reopened, it’s sending out monks to repopulate other disused monasteries.

Monastery of St Timothy

Situated just beyond the village of Timotesubani is the Monastery of St Timothy. Here the Church of the Virgin, built at the end of the 12th century, is famous for its frescoes, painted in 1205–15. This was one of the first churches in Georgia to be built in brick, but with a band and crosses of turquoise mosaic on the barrel dome.

The gate-tower, older than the church, is also of red brick, and there’s a 9th-century basilica next to the main church, with horrid new paintings. Entering through the south porch, built later in limestone, you’ll see plenty of bare brickwork, but also plenty of fine surviving frescoes, including a Virgin and Child above the altar, a Crucifixion to the south of the iconostasis, and Paradise at the west end; there are also plenty of saints and a flute-player in the north transept.

Betania Monastery

In the wooded Vere Valley, some 22km from Tbilisi, lies the monatery of Betania. Its church is a masterpiece of Georgian architecture and is also famous for supposedly housing part of the Virgin Mary’s robe. Set on a ridge, it’s surrounded on three sides by trees, with only its high barrel dome reaching above.

The monastery was founded in the 11th century, and the cruciform church was built in the 12th and 13th centuries; the frescoes were painted in 1207, and include one of just four portraits of Queen Tamar painted in her lifetime.

Jvari

The Jvari (Cross) Church stands on a spur of the Saguramo Hills, 150m above Mtskheta, and now seems to grow out of the rock. It’s one of the finest examples of old Georgian architecture, a marvellously simple but sophisticated edifice, in advance of most European ecclesiastical architecture of the period.

Built between AD586 and 604 by Patriarch Stephanoz I, it was the first ‘apse-buttressed’ cruciform church, in which the gaps between the arms of the cross are filled by small chapels, producing a virtually perfect square ground plan; this allows a wonderfully lofty and spacious interior in which four pillars support an octagonal drum and a round dome covering the entire central space.

It stands on the spot where Nino first set up her cross overlooking the pagan shrines of Mtskheta; the ruins of a late 6th-century church survive just north of the present church, with the remains of a defensive tower to the northeast.

Cathedral of St George

Founded by St Joseph, another of the Assyrian Fathers, the present church at Alaverdi was raised in the early 11th century, and is one of the largest medieval churches built in Georgia. Built of shirmi, the tuff stone ubiquitous in Kakheti and Armenia, it was damaged by the Mongols (with repairs in brick in the late 15th century), by Shah Abbas in 1616, and again by an earthquake in 1742, after which it was restored by Erekle II.

It was surrounded with defensive walls in the early 18th century, with the gate-tower added in the following century. From the destruction of the Bagrat Cathedral in Kutaisi in 1691–2 until the construction of Tbilisi’s Sameba Cathedral in 1995–2004, this was the highest church in Georgia, its dome rising 50m from the ground.

The interior is pretty worn; frescoes from the 11th to 13th centuries and the 15th century were whitewashed by the Russians in the 19th century, and gradually uncovered and restored from 1967. They include St George over the outside of the west door, the Virgin and Child over the altar, and others in the south transept.

There’s supposedly a hand carved in relief on a flagstone to the left inside the entrance; the story goes that a local prince was captured by the Turks, and before being killed cut off his hand, so that it could be taken home and buried in holy ground.

Kintsvisi Monastery

It takes about 40 minutes to walk up to the monastery from the village of Kintsvisi, climbing from fields to oak and beech forest to the lower edge of the conifer belt.

Built in 1207–13, of brick despite standing on limestone hills, the Church of St Nicholas has a single-bay nave and aisles, with a large porch to the west and others to the north and south. Its frescoes are absolutely magnificent, in particular the 13th-century Resurrection on the north side (including a stunning image of the Archangel Gabriel), and a Virgin and Child in the apse, as well as portraits of royalty (including one of the four surviving portaits of Queen Tamar painted during her lifetime).

There’s also the small stone Church of St George, probably also built in the 13th century, to the west of the main church, and the eastern half of the 10th-century Church of the Virgin poised on the edge of the hill to the west, rather exposed to the elements but still in good condition. A fourth church has recently been built over the grave of the abbot who died in 2006.

Vardzia

This is the country’s most famous cave-city and, largely because of its connections with Queen Tamar, a place of almost mystic importance for most Georgians. It’s said that its name derives from ‘Ak var, dzia’ or ‘Here I am, uncle’ – Tamar’s call when lost in the caves.

First established by King George III in 1156 and consecrated in 1185, his daughter Tamar made it into a monastery, which became the chief seminary of southwestern Georgia (housing 2,000 monks) until an earthquake ruined it in 1283, slicing away a large portion of the rock face, weakened by tunnelling.

Another quake in 1456 was followed by a Persian army in 1551, and it was abandoned after an attack by the Turks in 1578, so that now around 600 chambers survive of a total 3,000, which included stables, barracks, bakeries, wine presses and stores. Likewise, only half a dozen levels remain of the 13 which once penetrated 50m into the cliffs. Vardzia has been protected since 1938; there was some heavy-handed restoration with concrete in the 1970s, but more recent work has been more sensitive.

Davit-Gareja

In what is now virtual desert on the Azerbaijani border at 400–878m is a group of cave monasteries founded in the mid 6th century by St David, and his disciple Lukian, after his stay on Tbilisi’s Holy Mountain. Over two dozen monasteries have been identified, but only a few are widely known or visited and just three are in use.

Lavra Monastery

It was founded by St David in the 6th century and is now occupied by notoriously fundamentalist monks who take great exception to noise and especially to inappropriate clothing. Tourists are not allowed in the inner court or, of course, the monks’ cells.

Inside, go down to the lower court: David and Lukian are buried here in the Church of the Transfiguration or Rock Church (plain and with modern icons), near a spring known as the Tears of David. The diagonal lines of the rocks above the outer court and the cells are striking, and very photogenic; channels also lead water off the bare rocks outside the main doorway.

Udabno Monastery

Constructed between the 8th and 10th centuries, on the far side of the ridge, this is in both religious and artistic terms the most important of the monasteries.

The main church has superb frescoes from the late 10th and early 11th centuries, including the life of St David on the north wall (with a deer feeding on milk), the Virgin and Child in the apse, a Last Judgement on the east wall, and a Deesis in the east apse. From the ridge itself you have superb views across the desert, deep into Azerbaijan, and there are amazing sunsets here.

More information

Discover more about Georgia’s monasteries with our comprehensive guide: