Historical Ottoman conquest over the Balkan Peninsula has always been a topic of considerable debate. For some reason, the region’s Muslim history – like Europe’s Muslim history – tends to be remembered negatively, when it is remembered at all. Very little has been written about the fabulous architecture, the fascinating culture or tolerant attitudes that the Ottomans brought with them to the region.

The following list showcases some of the best Ottoman wonders in the Balkans, offering an insight into the beauty they left behind.

Tetovo Mosque (Šarena Džamija), North Macedonia

The most celebrated landmark in Tetovo, situated in the town centre just south of the river, the Šarena Džamija (literally ‘coloured’ or ‘painted mosque’) is known locally as Pasha Djamija (Prince’s Mosque) and often called the Motley Mosque by English-speakers. Its colourful exterior makes the building look like it is clad in a deck of playing cards, and over 30,000 eggs were used to manufacture the paint and glaze.

The mosque stands in landscaped green grounds that contain an octagonal turbe (grave) of Hurshida and Mensure, the two women who paid to have the mosque built in the mid 15th century. The original structure burned down in the 16th century and has undergone several restorations since then, the most extensive of which occurred in the 1820s under Pasha Abdulrahman, who added the colourful veneer for which the mosque is now famed.

Mustafa Pasha Mosque, North Macedonia

The largest and most decorated of all the mosques in Skopje was built in 1492 at the order of Mustafa Pasha while he was Vizier of Skopje under Sultan Selim I. The entrance to the mosque is through a four-column porch, which is crowned with three cupolas, and a 124-step white minaret rises from its western end. Inside, the pulpit and prayer recess are made from intricately worked marble and the walls are of a beautiful blue pattern work.

The five windows in each wall are staggered, rising up the walls of the mosque to create a pyramid effect. Despite having stood the test of time well, the mosque did have to undergo major restoration after the earthquake of 1963 and was refurbished again through Turkish funding over a five-year period ending in 2011. In the grounds of the mosque are Mustafa Pasha’s mausoleum and his daughter Umi’s sarcophagus.

Blagaj Tekke, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Blagaj Tekke is one of the most mystical destinations in all of BiH. When the Ottomans arrived, the sultan immediately ordered a dervish tekija (house/monastery) to be built at the source of the River Buna; as one of the largest water sources in Europe it boasts an average flow of 40,000 litres per minute – larger than the source of the Danube River. This tekija was built in the 1500s for the dervish cults at the base of a 200m cliff wall.

The tour of the tekija is self-guided and is most interesting for its woodwork and well-preserved old-style sitting and prayer rooms. The tekija has become a very popular tourist destination with busloads of travellers from Turkey arriving regularly, and its original peaceful and laid-back ambience is best experienced off-season. There is also a small trail across the wooden footbridge that leads almost directly to the cave where the Buna exits and which is a great place to capture the whole tekija house for a photograph.

Sulejmanija Mosque, Bosnia and Herzegovina

It’s hard to miss the Sulejmanija Mosque (Coloured Mosque). With its bright colours and unusual intricate artistic details on the outside walls, it is one of the most beautiful mosques in the Balkans. The old wooden doors are equally impressive and if the door is open and it is not prayer time you are welcome to enter. Remember to take off your shoes and if you are a woman to cover your head with a scarf or shawl.

The mosque is a unique example of Islamic architecture: its exterior is decorated with floral ornaments (motifs of grapevines, grapes and cypress flowers), which is unusual for an Islamic place of worship. The minaret is on the western instead of the eastern side. The building itself is a mixture of secular and religious architectural elements. It is believed that some hairs from the beard of the prophet Muhammad, given to Sulejman-pasha Skopljak as a high military award, are kept in the building. It was built in the early 16th century by Gazi-agha.

Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Višegrad is most famous for the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge, or Bridge on the Drina, a magnificent Ottoman bridge spanning the wide river that gained fame from Nobel-Prize winner Ivo Andrić’s novel, The Bridge on the Drina. One of three UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Bosnia and Herzegovina, it was first built in 1577 and though it suffered heavy damage during the wars of the 20th century, it has mostly been restored back to its original glory, thanks to recent investment in its reconstruction and revitalisation.

Characteristic of the apogee of Ottoman monumental architecture and civil engineering, the bridge has 11 masonry arches with spans of 11–15m, and an access ramp at right angles with four arches on the left bank of the river. For the wandering soul it’s an interesting place to sit and soak up the energy of the Drina racing below. The villagers may look at you with a bit of suspicion at first but after the first rakija you’ll have made some new friends.

Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Mostar is unique in that it has opened many of its most precious and historical mosques to be visited and viewed by tourists. This one was built in 1617 and although heavily damaged during the last war, it has been fully restored. Visitors are permitted to enter the mosque, and even climb the minaret for a phenomenal view of the Stari most.

You must take your shoes off before entering a mosque. As this mosque is open for visitors, it is not required that women wear a headscarf. On the same premises you will find a madrasa, which was built in the 17th century. It is recommended to visit in the morning in order to avoid the crowds.

Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque is perhaps the finest example of Ottoman Islamic architecture on the Balkan peninsula. The Persian architect, Adžem Esir Ali, was the leading architect of his time within the empire and his mosque design favours the early Istanbul style. The original structure was built in 1530 but was largely destroyed when Eugene of Savoy plundered Sarajevo in 1697. The last reconstruction of Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque was in 1886.

Although it was damaged during the last conflict, most of its precious original oriental design survived unscathed. It is important to stay to the side during prayer time as it is the main mosque in the city and is usually filled by local worshippers. No need for shyness, they are used to visitors and simply expect them to be courteous and follow the rules.

Altum Alem, Novi Pazar, Serbia

Novi Pazar is a town with one of the most pronounced Islamic atmospheres in Serbia: instead of church domes, it is minarets that stab the skyline. True to its Ottoman roots, the town today feels more like Turkey than anywhere else in Serbia; indeed, it is probably closer to old Turkish traditions than a lot of Turkish Mediterranean towns that have embraced mass tourism in recent years.

One standout Ottoman treasure is the 16th-century mosque of Altum Alem, the most important Turkish building in the town. Altum Alem, built by the master builder Abdul Gani, is of a square plan, with a dome and a spacious porch covered with cupolas that are not typical for the region. There is a wooden gallery and a colourful mihrab within. Access to the mosque can be gained through a courtyard which houses several Ottoman-period graves and the entrance to an Islamic school.

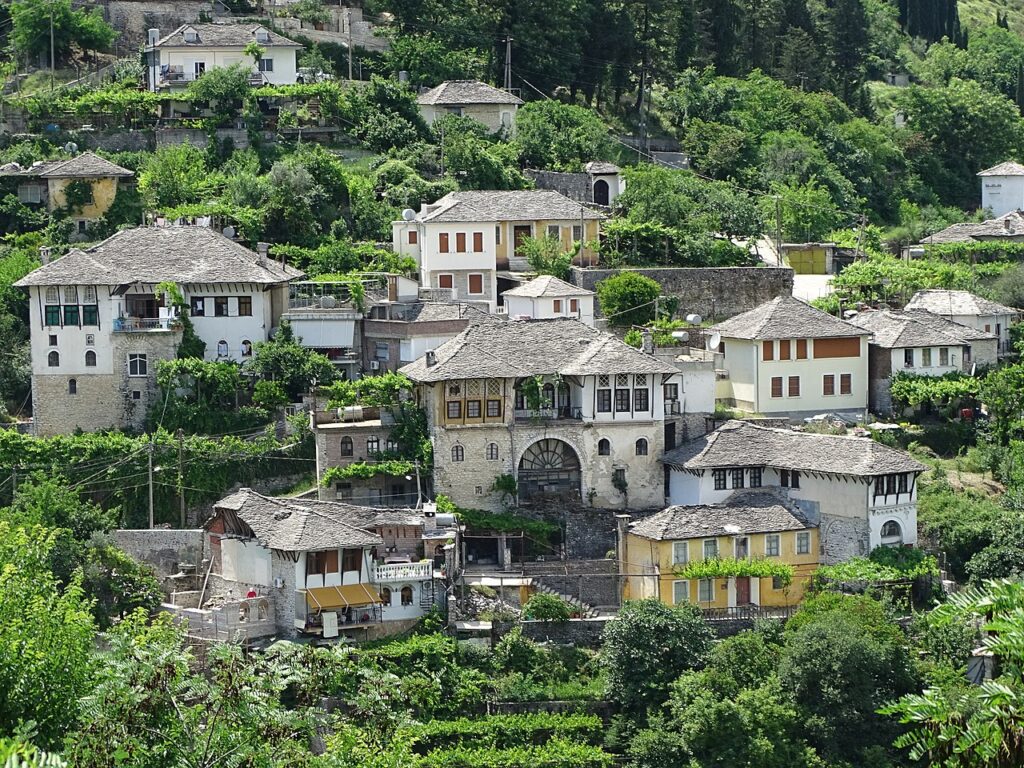

Gjirokastra, Albania

Although based on standard Ottoman architectural principles, the beautiful 19th-century houses of Gjirokastra are unique. In Gjirokastra, no traditional house is quite like another, although they have been classified according to certain design characteristics such as the number of wings that they have.

Many of the best examples of Gjirokastra domestic architecture were built in the first three decades of the 19th century. The houses are characterised by their defensively designed lower floors, with narrow entranceways and small windows set high in the wall. The entrance arches (qemeret) are made of dressed stone, often worked with great skill and refinement, and engraved with images of animals or birds; their wooden doors are also decorated with carvings. The ground floor of the house was traditionally used for storage and had a cistern (stera) into which rainwater was piped from the roof.

The mosques of Berati, Albania

Berati’s historic mosques are located fairly close together near the modern town centre. The Bachelors’ Mosque (Xhamia e Beqarëve), on the main boulevard, was built in 1827 for the use of the city’s (unmarried) shop assistants, and its external walls are beautifully decorated with wall paintings. The Leaden Mosque (Xhamia e Plumbit), so-called from the covering of its dome, dates from the first half of the 16th century. It is mentioned by the great Ottoman explorer Evliya Çelebi (1611–82).

The oldest of the three – and one of the oldest mosques in Albania – is the King’s Mosque (Xhamia e Mbretit), at the foot of Rruga Mihal Komneno, the street up to the castle. It has a beautifully carved and painted wooden ceiling, and a large women’s gallery. It is possible to see inside the mosque immediately after prayer times; at other times it is usually locked, although it can be opened for group visits.

Podgorica clock tower/Turkish Baths, Montenegro

Podgorica’s 18th-century clocktower is iconic. Standing some 30m high, it is the city’s most complete remnant form the Ottoman period and, despite being totally at odds with the chaotic modern surroundings, the tower (which doesn’t actually have a clock) stands its ground quite admirably.

The clocktower aside, the other most significant Ottoman landmark in the city is is the old Turkish Baths (hammam), secreted away under the New Bridge (Novi Most) in the Ribnica River gorge, a 10-minute walk east of the Old Town – a set of steps next to the bridge leads down to them.

More information

For more information, check out our books: