Turtles constitute some of our most endangered species. Thankfully, there are a number of fantastic conservation projects across the world that not only protect the turtles from the many threats that they face in the modern world, but also provide the visitor with a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Experience the breathtaking sight of a female turtle laying her eggs, or hundreds of hatchlings making their way to the sea for the first time, in the knowledge that doing so allows this beautiful cycle to continue for years to come.

We take a look at some of the best places to see turtles around the world.

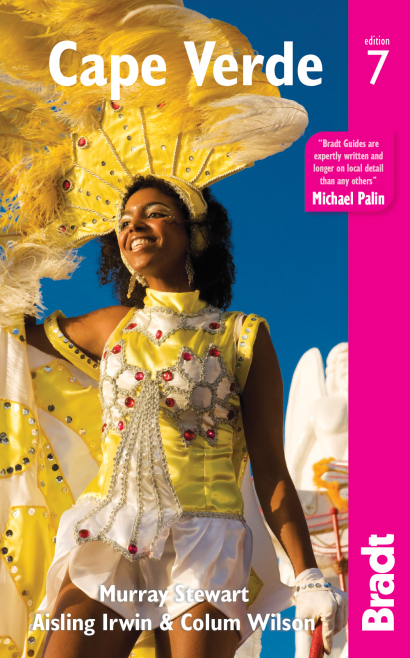

Cape Verde

Marine turtles are some of the most important species on the islands, and the archipelago is an important feeding area for five species. Research has shown that Cape Verde is a crucial participant in the life of the loggerhead turtle, the population being the third largest in the world after the Florida Keys in the United States and Oman’s Massirah Island. In the Atlantic, it is the second largest. One estimate states that about 3,000 breed annually in Cape Verde, though the figure varies enormously from year to year. The favoured island is overwhelmingly Boavista, probably followed by Maio, then Sal and all the other islands.

Watching nesting loggerhead turtles is a night-time experience, with August the peak of the nesting season. On Boavista there is an 80-minute journey to the southeastern coast. A guide gives a briefing on turtle biology and conservation work in Cape Verde as well as the basic rules to follow to minimise disturbance to the animals. Seeing turtles is guaranteed; witnessing their egg laying is more hit-and-miss as it depends on their finding a suitable nesting site.

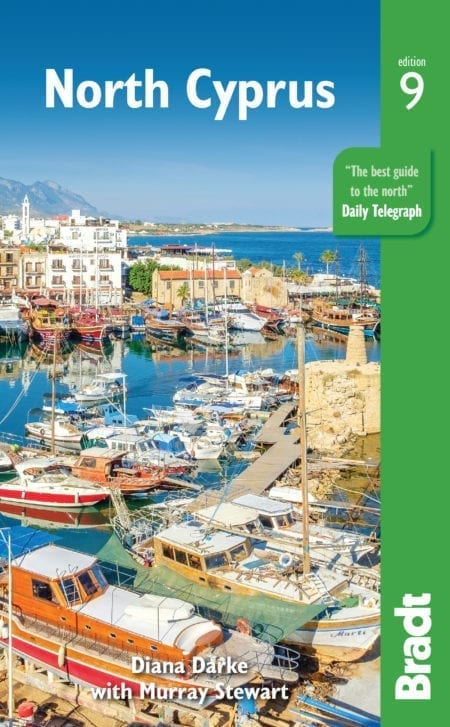

North Cyprus

Both loggerhead and green sea turtles choose to nest on the beaches of North Cyprus. Approximately 10% of the Mediterranean’s loggerhead turtles and 30% of its green turtles now nest in North Cyprus, making it a crucial site for the survival of both of these endangered populations.

Society for Protection of Turtles (SPOT) volunteers take one group of up to 15 individuals per night to Algadi Beach to observe nesting turtles during June and July. There’s no guarantee of sightings, but most people get lucky and as nesting numbers are on the up, the chances are increasing year on year. The experience is amazing. You could be waiting on a cool, breezy beach for at least an hour, so dress accordingly – June, in particular, can be very chilly at night. Visitors can bring blankets and sleep out until a volunteer wakes them and guides them to a nesting turtle. No flash photography is allowed.

From late July to late September larger groups are invited to see hatchling turtles emerge from their nests and be released to the sea during organised nest excavations and hatchling releases. This is the best opportunity to see and photograph baby turtles, though handling them is not possible. Hatchling releases – for which reservation is required – take place after 21.00, when the beach is closed to the public. Here, visitors get to handle, name and release their own hatchling sea turtle under the guidance of experienced volunteers. Again, no flash photography is allowed.

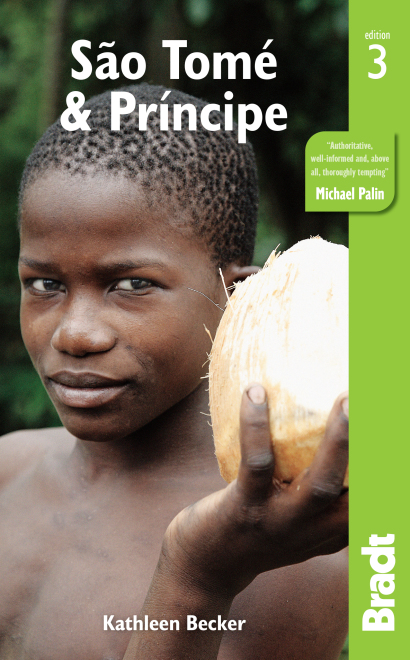

São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe has the most diverse range of sea turtles (tartarugas) in central Africa, with four of the five species nesting here. Sea turtles belong to the most ancient reptile family (Chelonidia), and have been around for some 200 million years. Marine turtles migrate several thousand kilometres from their foraging grounds to their nesting sites where they deposit several clutches of eggs between October and February, mainly at night. Today, they are all endangered.

The turtle has a special place in Santomean folklore, as a heroic creature that by clever and astute actions manages to outfox its opponents; the turtle is indeed seen as the equivalent to the fox in Western fairytales. Always hungry, Senhor Tartaruga (Sum Tataluga, in the national creole) is usually trying to work out new ways of finding food – if need be, behind the back of his family. In local culture, the turtle is, however, also a symbol of courage and resistance; accordingly, the forro expression clocon tataluga (coracao means ‘heart’) refers to a fearless person.

In São Tomé, the MARAPA conservation and fishing organisation looks after turtle projects and the burgeoning ‘turtle tourism’. MARAPA discourages tourists from paying locals to liberate turtles if they see them being caught, as it encourages the practice even more. There is a good display on turtles and their protection in the museum in São Tomé town. The stretch of beach between Praia Micoló and Morro Peixe is probably the most famous for turtles on São Tomé; all four species come here to lay eggs.

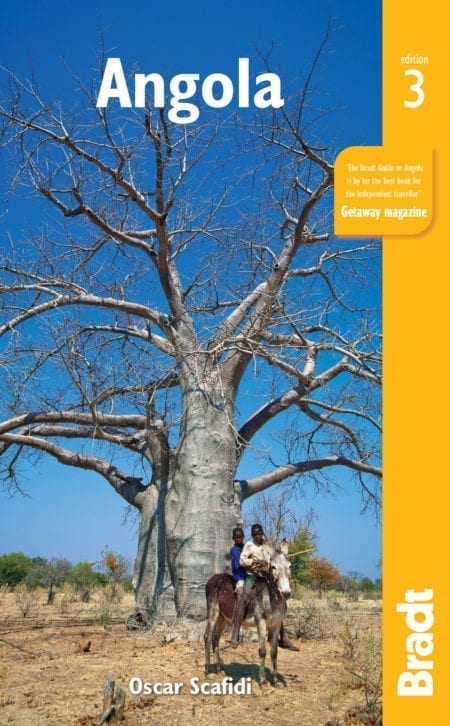

Angola

Around October every year olive ridley sea turtles come ashore on Turtle Beach to lay their eggs, which hatch around January. To ensure their safe passage, Angola LNG joined together with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) to create two sea turtle conservation programmes: Project Sereia and the Kwanda Island Sea Turtle Conservation Program.

Turtles live in deep water – anywhere between 1,000m and 2,000m – and come ashore in groups to lay and bury their eggs in holes that they dig with their flippers. Each nest contains between 100 and 130 eggs. The baby turtles hatch a couple of months later, always at night when the temperature is lower. The university marks each turtle nest with an empty plastic water bottle stuck on a pole in the sand. Nest density here is about 32 nests per square kilometre, but further south density for other types of turtles can get as high as 160 per square kilometre.

The beach below the Miradouro da Lua is an important nesting site for these endangered turtles. Little is known about turtles in Angolan waters but the Agostinho Neto University in Luanda has set up a turtle-tracking study on the beach. There are limited opportunities to get involved in an annual turtle-tracking weekend and details are posted on the website of the Angola Field Group.

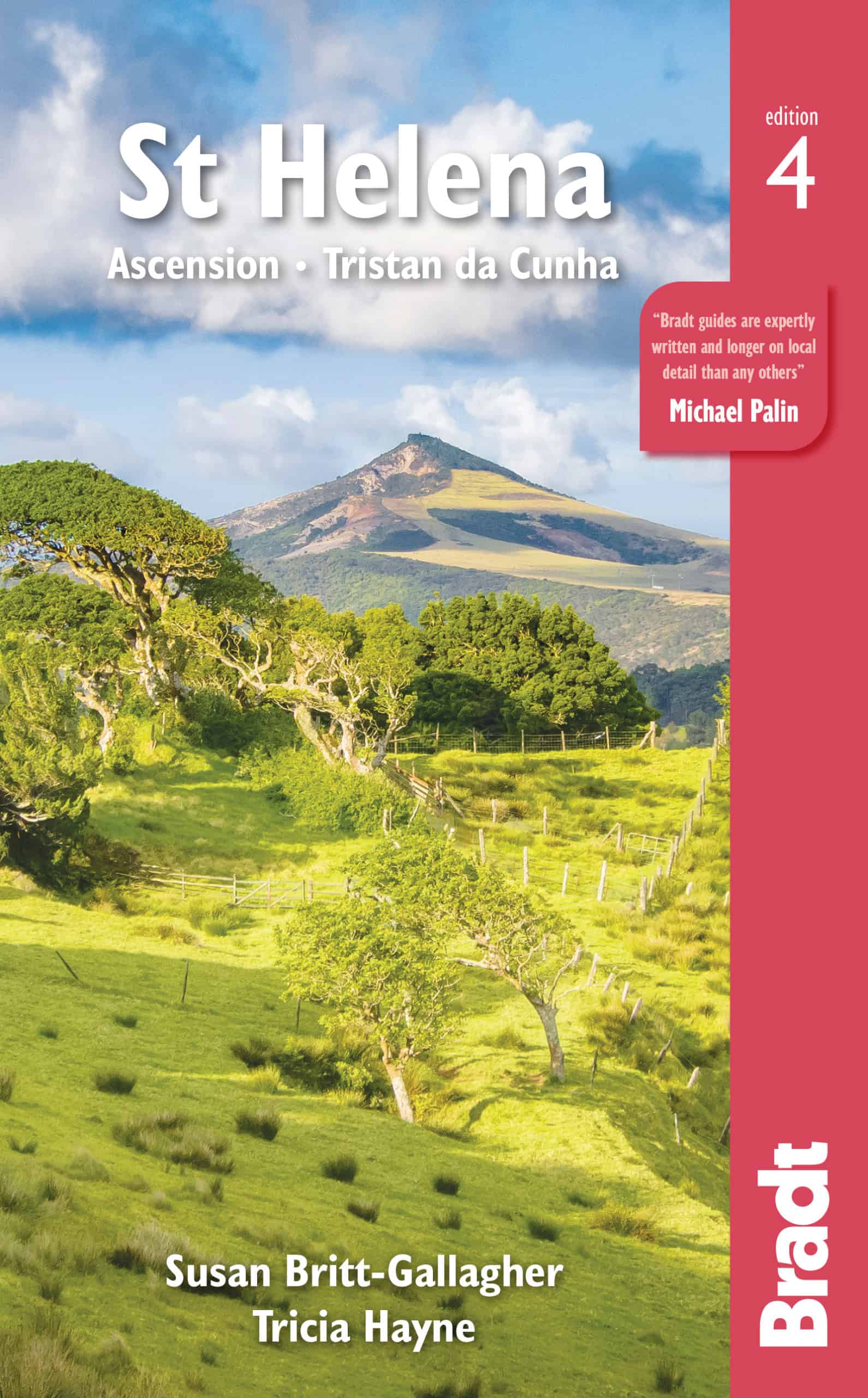

St Helena and Ascension Island

Of the two species of sea turtle in these waters, the smaller hawksbill turtle is present all year. Its exquisite shell is the source of the traditional ‘tortoiseshell’, long coveted for ornamental purposes, but now firmly outlawed under the CITES convention as well by local ordinance. Small specimens of the green sea turtle can also be seen at any time, but during the early months of the year they are occasionally joined by mating females who – like their counterparts on Ascension – are likely to have undertaken the long journey from Brazil to lay their eggs on these shores. Sadly, sandy beaches are not a feature of St Helena, though occasionally a few turtles are known to make their way ashore in Sandy Bay.

In marine terms, Ascension island is best known for the green sea turtle. As long as anyone can remember, Ascension’s beaches have served as the second-largest breeding ground in the Atlantic of these turtles. Every year, the animals migrate to the island from their feeding grounds, some 1,367 miles (2,200km) to the west along the South American coast. Many of the females come ashore to lay their eggs on Long Beach in Georgetown, where there are regular turtle tours in season. Out at sea, you may also see juvenile hawksbill turtles.

During the nesting season, around January to June, green sea turtles can be observed after dark on Long Beach in Georgetown, laying their eggs in the sand and then returning to the ocean. The turtles and their nest sites are fully protected and it is an offence to disturb them in any way.

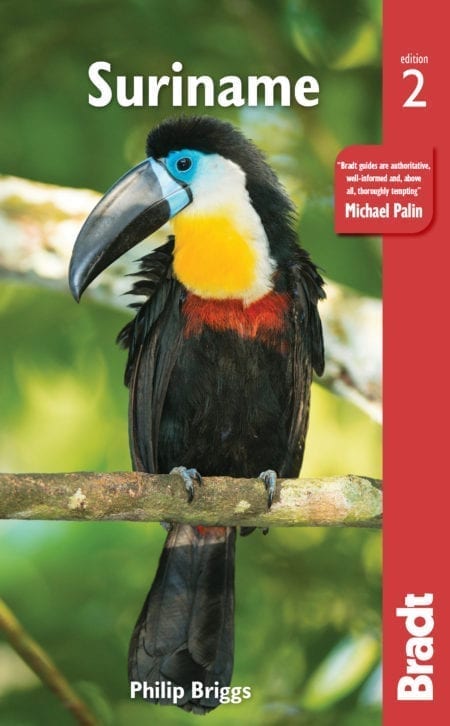

Suriname

From March to August, the sandy beaches of Suriname, particularly Galibi and Matapica, serve as nesting grounds for four of the world’s seven species of marine turtle, all of which appear on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Most common are the green turtle and leatherback, but the beaches also attract small numbers of olive ridley and hawksbill turtles.

The four species of marine turtle that nest on the beaches of Suriname are all listed as endangered due to global threats such as habitat destruction, direct harvesting for food, incidental capture by fishermen, and eggs being preyed upon by domestic animals.

People seldom have an opportunity to observe turtles in the wild because they are so rare and difficult to find. However, tourists who visit the Surinamese beaches of Galibi, Matapica and Braamspunt during the nesting season of February to July (sometimes running into August) are provided with an excellent chance of watching a sea turtle come ashore to nest.

Oman

The protected turtle-breeding beaches at Ras Al Jinz are a popular place to visit, with the turtles here a key element in the Omani government’s tourism strategy. There are seven sea turtle species in the world, of which five occur in Oman’s waters and four breed: the females of green, hawksbill, loggerhead and olive ridley turtle lay eggs on Oman’s beaches (so far no nesting by the fifth, the leatherback, has been reported). A visitor and research centre has been established at Ras Al Jinz, where an on-site ranger leads you to the sea’s edge in the dark for your night-time and dawn turtle-watching adventure.

A turtle-counting and tagging programme has also been set up on Masirah Island, one of the most important loggerhead sea turtle nesting sites in the world, with large numbers of loggerhead sea turtles laying their eggs annually. The importance of Oman for sea turtles is highly significant and the opportunities for turtle viewing excellent. Sea turtles, like all wild creatures, enjoy official protection in Oman.

Zanzibar and Mafia

The most commonly found turtle in Zanzibar is the green turtle, followed by the hawksbill. Both nest in Zanzibar. Leatherback and loggerhead are sometimes seen, but don’t nest. There have been no records of the olive ridley since 1975.

Zanzibar is not a major turtle nesting site, but appears to be a feeding ground for sea turtles from other areas; nesting is more prolific on Pemba. Conservationists have recovered tags from captured turtles showing that green turtles come to Zanzibar from Aldabra Island, in the Seychelles, and from Europa and Tromelin islands. Loggerheads that nest in KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa) also feed in Tanzania – one loggerhead was captured in Tanzania just 66 days after being tagged in South Africa.

On Mafia, the marine conservation NGO, SeaSense, is doing some marvellously successful turtle conservation and ecotourism work. Hatchings are utterly delightful to watch and community support for the project is genuine, profitable and sustainable. It’s a magical trip to see the baby turtles and well worth supporting.

More information

Learn more about the best places to see turtles with our guides: