Cumbria’s stone circles have long enticed wanderers fascinated by sites of celestial importance and none are more iconic than those found at Castleirgg. Did the Neolithic people who met amid the Cumbrian fells marvel at the magnificence of their surroundings? Did they come here to worship, to celebrate, give thanks, to mourn or to warn off malign forces?

The answers are beyond the realms of archaeology, but the circles of stone found in this special corner of England offer a small insight into the mysterious history of these unique monuments.

The stones of Castlerigg appeared out of the mist like a ring of wraiths enacting a solemn ritual. About 40 of them – some dwarfs, others 10ft giants – formed a silent circle amid the bare Lakeland fells. Were they a herd of enchanted, eternally milk-giving cows tricked by a jealous witch?

It was 05.30 on a summer morning and I was trudging across a wet field in search of this ancient monument, my head full of legends and whimsical nonsense I’d read about the origins of stone circles in Britain. Except that none of it felt so nonsensical then. The eastern horizon above the humps of Clough Head and Great Mell Fell was thick with inky rain clouds streaked with shafts of light. The stones stood their ground, defiantly erect, with faces of mottled grey hung with sinister lichen beards.

I had come alone at this unearthly hour hoping to have the place and its atmosphere to myself. But a flock of hooded crows had beaten me to it. Some were foraging in the middle of the circle while others perched on top of the stones. They made a hell of a fuss, cawing loudly into the damp air as they flapped off to sulk in a chestnut tree.

But I also stood my ground. I was soon seduced by this magic-tinged spot, surrounded by a 360° panorama of green fields and blue fells. I could only disagree with Keats, who once dismissed Castlerigg as ‘a dismal cirque of Druid stones upon a forlorn moor.’

Later that day I returned to Castlerigg with a head full of questions: who really built the stone circle? When? How… and why? With me was Robert Maxwell, an archaeologist working for the National Trust, which owns and looks after the site. I wanted the professional’s view. While we sheltered from a heavy shower in the lee of one of the largest stones, Robert told me, ‘The first thing to understand about stone circles is that there are far more enigmas than “right” answers.’

However, there is general agreement that it was Neolithic, or late Stone Age, farming communities in Britain that first started erecting slabs of rock into circles from around 3000 BC. The practice appears to have lasted a couple of thousand years into the Bronze Age. There are several hundred of these circles in Britain, along with ‘henges’ – circular earthwork banks and ditches – built in the same period.

Some, such as Stonehenge, are national monuments with ticket booths and turnstiles. Others are barely recognisable ruins, plundered over the centuries to build churches, houses or walls, and marked on maps simply as ‘Stone Circle’. Castlerigg seems to be one of the earliest but has survived pretty much unscathed, perhaps because it is so isolated. ‘So, what was the purpose of this place?’ I pressed. ‘Are the stones really astronomically aligned, as claimed?’

‘The trouble with looking at a place like this through 21st-century eyes is that we demand specific answers to specific questions’, said Robert. ‘Just imagine that you are a farmer a few thousand years ago, and that from time to time you and your fellow villagers get together in a common place with farmers from other settlements. You have had a good harvest, for which you give thanks to the sun. You swap your grain for a few tools and you have a chat about how to get things right. When the best time to plant is, for instance.’

Robert pointed to two different places high on the fells. ‘Up there is High Rigg where, from here, the sun rises on this point at Candlemas. Over there is Skiddaw, where the sun sets on the winter solstice. If I want to be sure to plant, or plough or whatever on a particular day of the year, how do I remember? How about lining up a stone, so that on the day the sunrise hits it…’ I was beginning to get the message – stone circles might have been ‘religious’, ‘social’ and ‘economic’. ‘But we don’t know, we don’t know.’

The modern-day functions of the circles also vary greatly. There are all those New Age powers that the stone circles are said to bestow upon believers. From time to time, for instance, Castlerigg hosts a Druid wedding. On the wet summer’s day of my visit, most of the visitors I spoke to were more down to earth. Hikers stopping at a point of interest on their route across the fells, or tourists with a guidebook entry to tick off. But there was also a sylph-like girl called Eustacia dressed in black with white hair right down her back, flitting from stone to stone. She offered this theory:

‘Ancient societies in Britain were matriarchal, and the earth was worshipped as a mother. Ceremonies were conducted by priestesses. By the Middle Ages, only traces of this religion remained in folklore, but those women who inherited them were the ones branded as witches.’

Then she pointed to a chestnut tree, where the crows I had banished that morning were still in raucous residence. ‘Those birds could be the reincarnated souls of those witches burnt at the stake or drowned,’ she said in deadly earnest.

More information

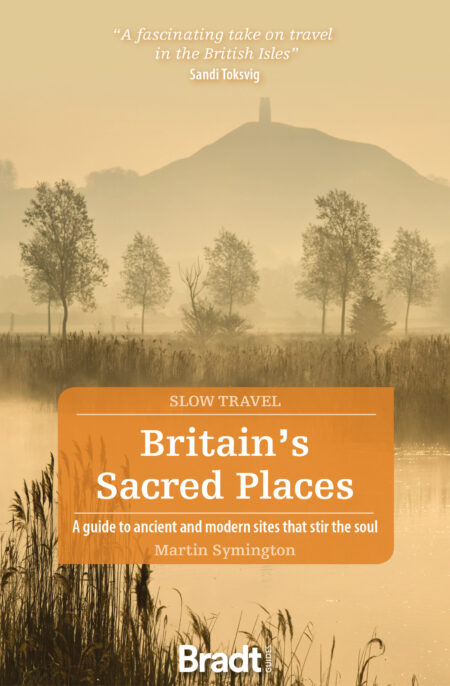

For more ancient sites and soul-stirring travel, check out Martin Symington’s guide: