Think Chester, think Romans. Yet, they were not the only contributors to the creation of one of Britain’s prettiest cities, enhanced by its setting on the banks of the River Dee. The visible layers of Chester’s history – Roman, medieval, Tudor, Georgian, Victorian – provide a charming place to wander down the ages, best done on the ancient walls that clasp its heart.

But there is more to the city than just its history: there is lots to do here amid the bustling streets, with plenty of shops, restaurants, pubs and cafes, and a lively arts scene. Here is a rundown of some of the highlights.

The city walls

Chester is defined by its city walls, the most complete Roman and medieval walls in the UK. Once, they ensured protection for those who dwelt within; today, properties inside this ring of stone are Chester’s most desirable addresses. Beautiful in themselves, the walls also provide visitors with the perfect elevated overview of the city; from the ramparts, you can orientate yourself quickly and easily, circumnavigating the historic centre and passing many landmarks along the way.

The original walls are thought to have been built from turf in about ad75 but were soon replaced with a stone version, the earliest section of which can be seen from Northgate, looking east. At some point the Romans did a repair job using gravestones, which were uncovered in the 19th century and now provide the most impressive display in the Grosvenor Museum. It’s thought that the Anglo-Saxon queen Aethelflaed extended some sections, which were further improved by the Normans and enhanced by the Georgians, who repaired much of the damage sustained during the English Civil War.

The Georgians were more interested in the walls for their recreational qualities than as defences, using them as a place to promenade and even widening parts to enable couples to stroll side by side (think of the size of women’s skirts in those days). They also transformed the main gates into archways so that coaches could pass through. The Victorians removed sections to connect a road to the Grosvenor Bridge and to enable the passage of the railway, with further adaptations in the 20th century.

Regardless of which gate you choose to start from, the mile-long walls will transport you to almost all the main city highlights, including the cathedral, the Roman gardens and amphitheatre, the Dee and the Roodee racecourse. Meanwhile, you can examine the walls’ own sights as you go, including the ornate Eastgate clock, a favourite image for postcards, built for Queen Victoria’s Jubilee, and the King Charles Tower from where Charles I is said to have watched his troops retreat from the Battle of Rowton Heath.

The Rows & city centre

Chester’s unique Rows provide a very different perspective to your usual shopping centre. The city’s four main streets – Eastgate, Watergate, Bridge and Northgate –all have walkways at the first-floor level and open on one side to the street. The Rows are reached via flights of stairs, while the premises beneath them are lower than street level and generally entered down a few steps.

Embellished in Tudor times with half-timbered structures, a style amplified by the Victorians, the Rows provide one of the prettiest aspects of the city, especially if you’ve come here just to shop. The layers of architecture also constitute a treasure hunt; the Guild of Chester Tour Guides runs a monthly ‘Rows Revealed’ tour that uncovers some astonishing remains, including pillars from the Roman fort in Pret a Manger and a Tudor plasterwork trail in Sofa Workshop that suggests Catherine of Aragon once visited the city.

Beyond the Rows, these four main streets, pedestrianised in part, are where you’re most likely to browse. The main shopping avenue is Eastgate Street, which is also the location of two high-class establishments: the venerable Chester Grosvenor Hotel and its Michelin-star restaurant and the department store Browns of Chester (now part of Debenhams), which was regarded as so posh that some people would dress up to go shopping in its hallowed halls. Watergate Street has an array of independent shops and is the address of Booth Mansion, a magnificent Grade I-listed Georgian property that became the assembly rooms of the period and is now home to an art gallery and tea room.

The corner of Eastgate Street and Bridge Street is a much-snapped example of the 19th-century black-and-white revival architecture found throughout the city, while Northgate Street is the home of the Town Hall, a triumph of the Gothic revival style. All four streets pivot on The Cross, a former marketplace with a medieval High Cross at its centre (the Roman headquarters was also hereabouts). The town crier makes a daily proclamation from here during summer. In fact, Chester has two town criers, husband-and-wife team David and Julie Mitchell, who celebrated their 20th anniversary in the post in 2018.

Roman Chester

It took until the early 20th century to unearth Chester’s Roman amphitheatre, hidden beneath buildings between St John the Baptist Church and Newgate for 2,000 years. Only a portion has been uncovered, about two-fifths of what is thought to be the largest amphitheatre in Britain, dating from the 1st century ad. In its heyday, this was a place for military training, executions and entertainment, hosting everything from bear baiting to gladiator fights, with the capacity for about 7,000 spectators, and today it’s possible to get a sense of the amphitheatre as it must have been.

The locations of two of the original four entrances are visible (the main north entrance and the one in the east), the slopes from which have enabled archaeologists to estimate the depth of the oval-shaped arena floor. Modern concrete slabs filled with sandstone suggest the thickness of the outer wall, and replicas here include a shrine to the goddess Nemesis and a chain block on the arena floor to which animals and possibly humans would have been tethered.

Much of the amphitheatre is covered by listed buildings, so a 50-foot-wide trompe l’oeil mural has been painted on the wall of the southern walkway that skirts the site to suggest what the whole structure would have looked like, right down to the historical detail of the red-brown colouring of the arena wall.

Around the corner is the Roman Gardens, a small open-air gallery containing an assortment of fragments of the fortress that have been found in Chester since Victorian times, and which also celebrates the Romans’ role in developing gardening as a pastime. Sitting in the shadow of Newgate and the city walls, from where it can also be admired, this green corridor doubles as both a pretty and handy cut-through from Pepper Street to the River Dee.

The gardens first opened in 1949 but were extended and redesigned in 2000 in the shape of the symbol of Aesculapius, Roman god of medicine, which, in case you don’t know, is a rod coiled by a serpent, so one of the two paths is straight, and the other winding. Here you’ll find columns from the headquarters building and the exercise hall of the bathhouse, a reconstructed hypocaust, and three specially commissioned mosaics, one a replica of an image of a mythological creature, a design found in the city’s bathhouse.

The ancient columns are deftly reflected in the cypress trees planted here, and the benches from which you can take in the scene are suggestive of the seating that might have been sat on by a toga-clad frequenter of the caldarium. There is also a plaque commemorating the dead from the siege of Chester in the English Civil War, close to a part of the city walls that was breached when the Parliamentarians pounded it with cannon, the repairs for which are clear to see.

Chester Castle

Chester has such a strong story as a Roman fortress that its Norman castle does not enjoy the profile it might elsewhere. Yet, William the Conqueror established a motte and bailey castle here on the banks of the Dee in 1070 (probably where Aethelflaed sited a fort in the previous century) and it became the nerve centre of the powerful Earls of Chester. Later, Henry III and Edward I also used it as military headquarters during their campaigns against the Welsh, and the city’s Royalist governor, Lord John Byron, based himself here during the English Civil War.

The Agricola Tower is the main survivor of the first stone fort built in the 12th century, a gateway to the inner bailey containing the chapel of St Mary de Castro, in which there are some rare medieval wall paintings. The fort on view today was designed by Thomas Harrison at the turn of the 19th century, a well-regarded transformation with a sequence of buildings and columns in abundance, including the Shire Hall, barracks and armoury and a monumental Propylaeum, with a huge gateway and two pavilions colonnaded to the front and rear.

Today, the county court and Cheshire Military Museum can be found among these buildings, the latter charting four centuries of the Cheshire Regiment’s history.

Bedding down

The Outbuilding Oscroft, nr Tarvin. Don’t be underwhelmed by the name. While The Outbuilding is indeed a structure set in the yard of a working farm, it’s also a well-presented self-contained apartment. Clad in timber, with a sweep of glass doors at one end that lets the light flood in, this is an attractive and spacious place to stay, offering an open-plan lounge-diner with kitchenette, twin bedroom and bathroom. There’s also a small patio and double doors open onto the orchard, which you share with the resident chickens.

Oddfellows Hotel 20 Lower Bridge St, Chester. You’ll be in no doubt you’re in Cheshire when you step inside this quirky city-centre hotel with its bold Alice in Wonderland theme that plays on the county’s connection with the author Lewis Carroll. (Don’t be surprised to find a pair of giant wicker boxing hares or a table and chairs hanging from the ceiling.) There are 32 rooms divided between the original building and a new extension, plus four apartments.

More information

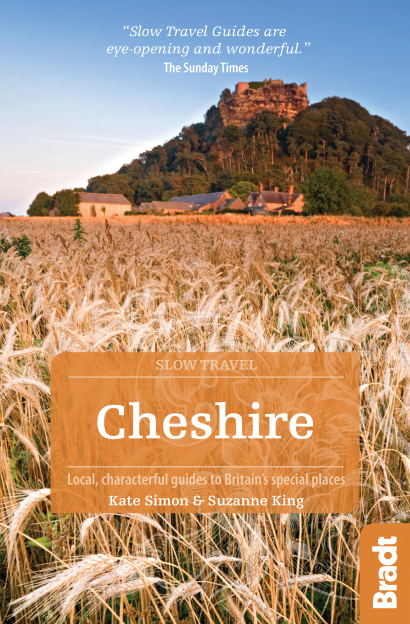

Want to know more about the region? Take a look at our Slow Travel guide.