In Botswana, animals wander freely across vast reserves which are measured in thousands of square kilometres, not merely hectares. Exploring these wilder corners is invariably deeply liberating.

Chris McIntyre, author of Botswana: the Bradt Travel Guide

From the parched Kalahari to the snaking waterways and wildlife-rich islands of the Okavango Delta, UNESCO’s 1000th World Heritage Site, and the eerie Makgadikgadi salt pans, northern Botswana’s vast natural wilderness is remarkable in its sheer variety. As the land dries up through the hot summer months, herds of game home in on the gradually diminishing waters, stalked by lion, leopard, and the endangered wild dog. Further north, the permanent waters of the Chobe River draw almost unimaginable herds of elephant and, increasingly, giraffe. And deep in the Delta, black and white rhino once again tread the land of their ancestors.

A safari in northern Botswana takes many guises. Explore from a vehicle, with front-row seats and scarcely another human being in sight. Drift through lily-strewn waters in a mokoro, the only sounds the swish of the reeds as they part in front of you, the gentle plop of a tiny reed frog, and the wings of a startled jacana. Or embark on a walking safari with an expert guide and encounter nature on its own terms.

And while you’re there, consider another facet of northern Botswana’s pristine wilderness: the ancient past. The natural art gallery of the Tsodilo Hills, where rock paintings date back thousands of years, and the archaeological remains of earlier settlements preserved on the great salt pans.

So much to see, so little time in one short holiday. No wonder northern Botswana becomes addictive.

For more information, check out our guide to Botswana:

Food and drink in Botswana

Food

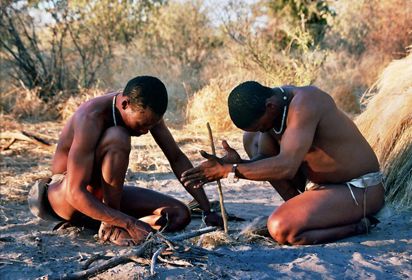

Talking of any one ‘native cuisine’ in Botswana is misleading, as what a person eats is dependent on where they live and the ethnic group they belong to. In the Kalahari and Okavango there was relatively little agriculture until recently; there, gathering and fishing, supplemented by hunting, provided subsistence for the various groups.

In the kinder climes east of the Kalahari, where there is enough rain for crops, sorghum is probably the main crop. This is first pounded into meal before being mixed with boiling water or sour milk. It’s then made into a paste bogobe – which is thin, perhaps with sugar like porridge, for breakfast, then eaten thicker, the consistency of mashed potatoes, for lunch and dinner. For these main meals it will normally be accompanied by some tasty relish, perhaps made of meat (seswa) and tomatoes (moro), or dried fish.

Maize meal, or papa (often imported as it doesn’t tolerate Botswana’s dry climate that well), is now often used in place of this. You should taste this at some stage when visiting. Safari camps will often prepare it if requested, and it is always available in small restaurants in the towns.

Camps, hotels and lodges that cater for overseas visitors serve a very international fare, and the quality of food prepared in the most remote camps is usually amazingly high. When coming to Botswana on safari your biggest problem with food is likely to be the very real danger of putting on weight.

Self-catering

If you are driving yourself around and plan to cook, then get most of your supplies in Maun or Kasane. Both have several large, well-stocked supermarkets and a number of more specialist shops. However, it is important to be aware that northern Botswana is effectively ringed by a veterinary fence – widely known as the buffalo fence – with regular checkpoints along the roads to help prevent infection of the country’s valuable cattle herds with foot-and-mouth disease. For this reason, taking red meat across the fence from a buffalo area into an area that is used for cattle farming is prohibited. Campers, take note!

It’s usually best to stock up with food at these main centres, as away from them the range will become sparser. Expect villages to have just a bottle stall, selling the most popular cool drinks (often this excludes ‘diet’ drinks), and a small shop selling staples like rice and (occasionally) bread, and perhaps a few tinned and packet foods. Don’t expect anything refrigerated.

Drink

Alcohol

Like most countries in the region, Botswana has two distinct beer types: clear and opaque. Most visitors and more affluent people in Botswana drink the clear beers, which are similar to European lagers and always served chilled. St Louis and Castle are the lagers brewed here by a subsidiary of South African Breweries. They are widely available and usually good. You’ll also sometimes find Windhoek lager, from Namibia – which is similar and equally good.

The less affluent residents will usually opt for some form of the opaque beer (sometimes called Chibuku, after the market-leading brand). This is a commercial version of traditional beer, usually brewed from maize and/or sorghum. It’s a sour, porridge-like brew: an acquired taste, and it changes flavour as it ferments; you can often ask for ‘fresh beer’ or ‘strong beer’.

As a visitor you’ll have to make a real effort to seek out opaque beer; most bars that tourists visit don’t sell it. Locals will sometimes buy a bucket of it, and then pass it around a circle of drinkers. It would be unusual for a visitor to drink this, so try some and amuse your companions. If you aren’t sure about the bar’s hygiene standards, stick to the pre-packaged brands of opaque beer like Chibuku.

Water

Water in the main towns is usually purified, provided there are no shortages of chlorine, breakdowns or other mishaps. It’s generally fine to drink.

Out in the bush, most of the camps and lodges use water from boreholes. These underground sources vary in quality, but are normally free from bugs and so perfectly safe to drink. Sometimes it is sweet, at other times the water is a little alkaline or salty. Ask the locals if it is suitable for an unacclimatised visitor to drink, then take their advice.

The water in the Okavango Delta is generally fine to drink. You’ll be expected to do so during most budget mokoro trips, which is fine for most backpackers who are in Africa for long trips. There are relatively few people living in the communities in the Delta; contamination levels are very low. However, if you’ve a sensitive stomach, or are visiting for a short trip, then you’d be best to avoid it and stick to borehole water, or travel with a filter bottle.

Health and safety in Botswana

Health

Botswana is one of the healthiest countries in sub-Saharan Africa. It has a generally low population density, who are affluent by the region’s standards, and a very dry climate, which means there are comparatively few problems likely to affect visitors. The risks are further minimised if you are staying in good hotels, lodges, camps and guest farms, where standards of hygiene are generally at least as good as you will find at home.

The major dangers in Botswana are car accidents (caused by driving too fast, or at night, on gravel roads) and sunburn. Both can be very serious, yet both are within the power of the visitor to avoid.

Visitors to Botswana should always take out a comprehensive medical insurance policy to cover them for emergencies, including the cost of evacuation to another country within the region. Such policies come with an emergency number (often on a reverse-charge/call-collect basis). You would be wise to memorise this, or indelibly tattoo it in as many places as possible on your baggage.

Personal-effects insurance is also a sensible precaution, but check the policy’s fine print before you leave home. Often, in even the best policies, you will find a limit per item, or per claim – which can be well below the cost of replacement. If you need to list your valuables separately, then do so comprehensively. Check that receipts are not required for claims if you do not have them, and that the excess which you have to pay on a claim is reasonable.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on ISTM. For other journey preparation information, consult NaTHNac (UK) or CDC (US). Information about various medications may be found on NetDoctor. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Botswana is not a dangerous country. If you are travelling on an all-inclusive trip and staying at lodges and hotels, then problems of personal safety are exceedingly rare. There will always be someone on hand to help you. Even if you are travelling on local transport, perhaps on a low budget, you will generally be perfectly safe if you are careful.

Outside of rougher parts of the main cities, crime against visitors, however minor, is rare. Even if you are travelling on local transport on a low budget, you are likely to experience numerous acts of random kindness, but not crime. It is certainly safer for visitors than the UK, USA or most of Europe.

To get into a difficult situation, you’ll usually have to try hard. You need to make yourself an obvious target for thieves, perhaps by walking around at night, with showy valuables, in a less affluent area of a town or city. Provided you are sensible, you are most unlikely to ever see any crime here.

Female travellers

When attention becomes intrusive, it can help if you are wearing a wedding ring and have photos of ‘your’ husband and children, even if they are someone else’s. A good reason to give for not being with them is that you have to travel in connection with your job – biology, zoology, geography, or whatever. (But not journalism – that’s risky.)

Pay attention to local etiquette, and to speaking, dressing and moving reasonably decorously. Look at how the local women dress, and try not to expose parts of yourself that they keep covered. Think about body language. In much of southern Africa direct eye-contact with a man will be seen as a ‘come-on’; sunglasses are helpful here.

Don’t be afraid to explain clearly – but pleasantly rather than as a put-down – that you aren’t in the market for whatever distractions are on offer. Remember that you are probably as much of a novelty to the local people as they are to you, and the fact that you are travelling abroad alone gives them the message that you are free and adventurous. But don’t imagine that a Lothario lurks under every bush: many approaches stem from genuine friendliness or curiosity, and a brush-off in such cases doesn’t do much for the image of travellers in general.

Take sensible precautions against theft and attack – try to cover all the risks before you encounter them – and then relax and enjoy your trip. You’ll meet far more kindness than villainy.

Travelling with a disability

For wheelchair users and people who have difficulties walking, Botswana is a relatively accessible safari destination. It is possible to book through a specialised operator and be sure that your needs are met, or to do enough preparation in advance and travel independently. Either way, with some endeavour, everybody can experience the unique highlights this country has to offer.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Homosexuality is illegal in Botswana, although no-one – as far as is known – has ever been prosecuted, and same-sex relationships have never been a problem for guests in safari camps. While it’s not at all unusual in traditional societies to see two men – or two women – casually holding hands, public displays of affection between two people (gay or straight) may create tension and are best avoided.

Travel and visas in Botswana

Visas

If you need a visa for Botswana, you must get one before you arrive. Currently, passport holders from numerous countries, including the following, do not need a visa and will be granted a 30-day entry permit on arrival (subject to payment of the tourism levy when it comes into operation):

Most EU (European Union) countries (except Cyprus, Hungary, Lithuania, and Malta – whose citizens do need visas)

• USA, South Africa, Scandinavian countries

• UK and most Commonwealth countries (except Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka – whose citizens do need visas).

For more details, contact your local Botswana embassy or high commission, which is also the best place to verify that the information here is still current. Alternatively, and to download a visa application form, check on the Botswana government website.

The prevailing attitude amongst both Botswana’s government and its people is that visitors are generally very good for the country as they spend valuable foreign currency – so if you look respectable then you should not find any difficulties in entering Botswana.

Given this logic, and the conservative nature of Botswana’s local customs, the converse is also true. If you dress very untidily, looking as if you’ve no money when entering via an overland border, then you may be questioned as to how you will be funding your trip. Very rarely, you may even be asked for a return ticket as proof that you do intend to leave. Dressing respectably in Botswana is not only courteous, but will also make your life easier.

Visa extensions

If you want to stay longer than 30 days, then you must renew your permit at the nearest immigration office; a fee of P100 is payable. For a visa lasting longer than 90 days, you should apply to the appropriate Regional Immigration Officer, preferably before entering Botswana. Note that it’s a serious offence to stay longer than 90 days in a 12-month period without permission.

Getting there and away

By air

The vast majority of visitors to northern Botswana fly via the gateways of Maun, which has an international airport, and Kasane, which is more effectively serviced by the nearby airports at Victoria Falls (in Zimbabwe) and Livingstone (in Zambia).

The national carrier, Air Botswana, does not fly outside southern Africa, and of the other airline links to Botswana, the most notable is Airlink, a subsidiary of South African Airways. A popular routing for visitors to the region is to fly to Livingstone (airline code LVI) or Kasane (BBK) via Johannesburg (JNB), then leave from Maun (MUB), again routing via Jo’burg . There are also regular flights between Maun and Cape Town.

However you arrange your flights, remember some basic tips. First, make sure your purchase is protected. Always book through a company that is bonded for your protection – which in the UK means holding an ATOL licence (Air Travel Organiser’s Licence) – or use a credit card.

Second, note that airlines don’t always give the best deals direct. Often you’ll do better through a discounted flight centre or a tour operator.

Third, book the main internal flights at the same time – with the same company – that you book your flights to/from Johannesburg. Often the airline taking you to Africa will have cheap deals for add-on regional flights within Africa. You should be able to get Jo’burg–Livingstone flights, or Maun–Jo’burg flights, at discounted rates provided that you book them at the same time as your return flights to Jo’burg. Further, if you book all your flights together with the same company, then you’ll be sure to get connecting flights, and so have the best schedule possible.

Overland

Typically overland border posts open for about 8–12 hours a day, from between 06.00 and 08.00 in the morning. That said, some of the busier ones on main routes stay open considerably longer than this.

To/from Zambia

Despite meeting Zambian territory only at a point, Botswana does have one border crossing with Zambia: a reliable ferry across the Zambezi linking Kazungula with its namesake village in Zambia.

To/from Zimbabwe

Botswana has several border posts with Zimbabwe, of which the two most important are the one on the road between Kasane and Victoria Falls, at Kazungula, and the one on the main road from Francistown to Plumtree (and hence Bulawayo), at Ramokgwebane. A third much smaller post is at Pandamatenga. This is 100km south of Kasane, and sometimes used by visitors as a neat shortcut into the back of Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park.

To/from Namibia

Despite the long length of its border with Namibia, Botswana has very few border posts here. The most important of these by far is the post on the Trans-Kalahari Highway, the route between the towns of Ghanzi and Gobabis.

The other two major crossings are at Mohembo (north of Shakawe and at the south end of Namibia’s Mahango National Park; and across the Chobe River at Ngoma.

Rather less well-known are three other possible crossings into Namibia. The first is at the Dobe border post, on the road between Tsumkwe, in Namibia, and Nokaneng, on the west of the Delta. The other two, geared to those spending time in lodges right on the Namibian border, are between Kasane and both Impalila Island and Kasika.

To/from South Africa

South Africa has always been Botswana’s most important neighbour politically and economically, and for many years (even before South Africa was welcome in the international fold) it was in a ‘customs union’ with South Africa and Namibia. Thus it’s no surprise to find a range of border posts between Botswana and South Africa.

Getting around

By air

There are two ways to fly within Botswana: on scheduled airlines or using small charter flights.

Scheduled flights

The national carrier, Air Botswana, operates the scheduled network. This is limited in scope, but generally very efficient and reliable. Air Botswana links Maun directly with Kasane, Gaborone and Johannesburg, while Kasane is linked to both Gaborone and Johannesburg.

Charter flights

Small charter flights operate out of the hub of Maun, with Kasane as a secondary focus, and ferry travellers around the camps of northern Botswana like a fleet of taxis. They use predominantly six- to 12-seater planes which criss-cross the region between a plethora of small bush runways. There’s no other way to reach most camps, but flights are usually organised by the operator who arranges your camps as an integral part of your trip, and you’ll never need to worry about arranging them for yourself.

By rail

There is a railway that links South Africa with Lobatse, Gaborone, Palapye, Francistown and Bulawayo (in Zimbabwe), but that’s the only railway in the country – so is rarely used by travellers to northern Botswana.

By bus

Botswana has a variety of local buses which link the main towns together along the tarred roads. They’re cheap, frequent and a good way to meet local people, although they can also be crowded, uncomfortable and noisy. In short, they are similar to any other local buses in Africa, and travel on them has both its joys and its frustrations.

There are two different kinds: the smaller minibuses, often VW combis, and the longer, larger, ‘normal’ buses. Both will serve the same destinations, but the larger ones tend to run to a timetable, go faster and stop less. Their smaller relatives usually wait to fill up before they leave the bus station, then go slower and stop at more places.

By car

Driving in Botswana is on the left, as in the UK, and seatbelts must be worn. If you’re planning to drive, you should have either an international driving licence or a photo licence, though generally we’ve found that an old-style British paper licence is acceptable. The standard of driving is relatively good, but traffic – and accidents – are increasing, so remain alert, and avoid driving at night in any circumstances.

Speed limits are generally 120km/h on major roads, decreasing to 80km/h outside towns and 60km/h in urban areas, with variations generally signposted. That said, travelling at 120km/h on even the best of Botswana’s tarmac roads is foolhardy, given the potential for animals such as goats and even elephants wandering across the road; stick to 80km/h. In national parks, there is a blanket limit of 40km/h – though you’ll rarely be in a position to come close to this.

The police have radar equipment, and actively set up radar traps, especially just outside towns. Speeding tickets, may sometimes be paid on the spot, against a signed receipt from the officer, but often you’ll have to report to the nearest police station within 48 hours. Botswana’s police are efficient; it’d be foolhardy not to obey such a summons.

When to visit Botswana

There simply isn’t one ‘best time’ to visit Botswana, or any of its wild areas. Most tourists visit during the dry season, from around May to the end of October. Within that season, the period from mid-July to mid-October is definitely the busiest – although Botswana’s small camps/lodges and private reserves ensure that it never feels busy, even when everywhere is full.

Most of those visiting outside of this season are cognoscenti, who visit early or late in the season – May to July or late October to November – when the camps are quieter and often costs are lower.

A much smaller number of visitors come during the rains, from December to April, when camps will frequently be quiet for days. This often means that they will give visitors a much more personal experience, with private drives; their rates are often lower too, and they’re usually far more flexible about bringing children on safari.

Much of the blame for this ‘glut or famine’ of visitors lies with overseas tour operators. Many who advertise trips here just don’t know Botswana well enough to plan trips which work during the rainy season. It’s much easier for them to make blanket generalisations, telling enquirers who don’t know any better that it’s ‘not interesting’ or that ‘you won’t see any game’ if you visit in the wet season. None of this is true, as long as you choose your destinations carefully, but of course most people don’t know this in advance.

While the rains are not the ideal time for everybody’s trip, they are a fascinating time to visit and should not be dismissed without serious thought.

The bottom line is probably that if game viewing is your overriding priority, or this is one of your first trips to Africa, then you’ll be better visiting during the dry season. Then the animals are much easier to spot, as no thick vegetation obscures the view, and they are forced to congregate at well-known water points, like rivers, where they can be observed.

Climate

Botswana is landlocked far from the coast and mostly in the tropics. It receives a lot of strong sunlight and most of the country is classed as either semi-arid or arid (the line being crossed from semi-arid to arid when evaporation exceeds rainfall). In many respects, most of central and northern Botswana has a subtropical ‘desert’ climate, characterised by a wide range in temperature (from day to night and from summer to winter), and by low rainfall and humidity.

Botswana’s climate follows a similar pattern to that found in most of southern Africa, with rainfall when the sun is near its zenith from November to April, and most areas receiving their heaviest rainfall in January and February. The rainfall is heavier in the north and east, and lighter in the south and, especially, the southwest. The precise timing and duration of the rains is determined by the interplay of three airstreams: the moist ‘Congo’ air mass, the northeastern monsoon winds, and the southeastern trade winds.

Itineraries

- Expert Africa is a UK-based specialised tour operator run by the author of the Bradt guide to Botswana.

- SafariBookings is a comparison website that lists Botswana safari holidays run by local and international tour operators.

Things to see and do in Botswana

Chobe River

Perhaps the park’s greatest attraction is its northern boundary, the Chobe River. In the dry season animals converge on this stretch of water from the whole of northern Botswana. Elephant and buffalo, especially, form into huge herds for which the park is famous.

The river meanders through occasional low, flat islands and floating mats of papyrus and reeds. These islands, and beside the river, are always lush and green – and hence attract high densities of game. Beside this the bleached-white riverbank rises up just a few metres, and instantly becomes dry and dusty. Standing on top of this are skeletons of dead trees, sometimes draped by a covering of woolly caper-bushes. In several areas this bank has been eroded away, perhaps originally where small seasonal streams have joined the main river or hippo tracks out of the water have become widened by general animal use to access the floodplains.

The game densities vary greatly with the seasons, but towards the end of the dry season it is certainly one of Africa’s most prolific areas for game. It is an ideal destination for visitors seeking big game. Elsewhere in the dry season you’ll find fascination in termites or ground squirrels, but here you can find huge herds of buffalo, relaxed prides of lion, and perhaps Africa’s highest concentration of elephant – huge herds which are the hallmark of the area.

One of the main attractions of the boat trips on the Chobe is that large family groups of elephants will troop down to the river to drink and bathe, affording spectacular viewing and photography. You’ll find these here at any time of day, but they’re especially common in the late afternoon, just before sunset.

Kasane

The administrative centre of Chobe District, Kasane is on the surface just a small town in the northeast corner of Botswana. It lies on the southern bank of the Chobe River, a few kilometres from its confluence with the Zambezi – where the borders of Zambia, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Botswana meet at a point. Thus, while the town is of limited interest in itself, it is an important gateway: to the Chobe National Park; to Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe and Livingstone in Zambia; to the road across Namibia’s Caprivi Strip; and to the small charter flights which ferry visitors between the various lodges in northern Botswana.

Construction of a new bridge over the Zambezi River at this point is bringing change to the area, with the neighbouring town of Kazungula gaining something of the air of a border settlement. Along with shopping developments and fuel stations, several small guesthouses are springing up to service the increasing and anticipated level of passing trade. There is even a set of traffic lights (locally known as a robot) – albeit designed to control access to the new fire station.

If you’re just passing through the area, it’s quite likely that you’ll come via Kasane, if only on a transfer bus. And if you’ve organised your own travelling then you’re likely to want to stop here, to refuel and refresh before continuing. But for many people, Kasane is a relaxing place to stay for a couple of days and to take advantage of its proximity to Chobe National Park, affording opportunities of boat cruises and game drives into the park.

Makgadikgadi Pans

The Sua and Ntwetwe pans that comprise Makgadikgadi cover 12,000km² to the south of the Nata–Maun road. The western side is protected within a national park, while the east is either wilderness or cattle-ranching land. These are amongst the largest salt pans in the world and have few landmarks. So you’re left to use the flat, distant horizon as your only line of reference – and even that dissolves into a haze of shimmering mirages in the heat of the afternoon sun.

During the rains this desolate area comes to life, with huge migrating herds of zebra, wildebeest, and occasionally (if the pans fill with water) pelicans and many thousands of flamingos. A couple of odd outcrops of isolated rock in and around the pans add to their sense of mystery, as well as providing excellent vantage points from which to view the endless expanse of silver, grey and blue.

Maun

This once-dusty, sprawling town has been the start of expeditions into the wilds since the turn of the century, and it is now the safari capital of the country. Maun’s elongated centre is dotted with modern shops and offices, and its suburbs – until recently dominated by traditionally built, thatched rondavels – glint in the sun reflecting off tin-roofed houses.

In the 1980s everywhere and everything here seemed geared towards the tourism bonanza. Maun had a rough-and-ready frontier feel, as contemporary cowboys rode into town from the bush in battered 4x4s. Its focal points were the camps north of town – Island Safari Lodge, Crocodile Camp, Okavango River Lodge – and the old Duck Inn opposite the airport.

Then, as Maun became the administrative centre for the northern and western parts of Botswana, government departments moved here en masse. The town’s roads became sealed tar, rather than pot-holed gravel tracks, which opened the door to an influx of saloon cars from the rest of the country. Finally the tourism product itself changed. The pendulum swung away from last-minute budget trips bought in Maun, to upmarket safaris booked in advance from overseas. The new breed of visitors just change planes here; they seldom spend more than a few hours at Maun Airport.

Moremi Game Reserve

Moremi Game Reserve protects the central and eastern areas of the Okavango Delta. It forms a protected nucleus for the many wildlife reserves/concessions in the region. Physically Moremi is very flat, encompassing extensive floodplains, some seasonal, others permanent, numerous waterways and two main land masses: the Mopane Tongue and Chief’s Island. Its area is defined in some places by rivers, although their names and actual courses are anything but easy to follow on the ground. Its northern boundary roughly follows the Nqoga–Khwai river system, while its southern boundary is defined in sequence by the Jao, Boro and Gomoti rivers.

The ecosystems here are among the richest and most diverse in Africa. Thanks to generally effective protection over the years, they have also been relatively undisturbed by man. Now with wildlife tourism thriving around the park as well as in the private concessions, we can be really optimistic about its future.

Elephant and buffalo occur here year-round in large numbers, and you’re likely to see blue wildebeest, Burchell’s zebra, impala, kudu, tsessebe, red lechwe, waterbuck, reedbuck, giraffe, common duiker, bushbuck, steenbok, warthog, baboon and vervet monkey throughout the park. Eland, sable and roan antelope also range across the park but are less common, as they are elsewhere in Africa. Sitatunga live deep in the swamps. Lion, leopard, cheetah and spotted hyena all have thriving populations here. Moremi is central to wild dog, which range widely across most of northern Botswana.

For bird lovers, Moremi boasts over 400 species, a great variety, which are often patchily distributed in association with particular habitats; though visiting any area, the sheer number of different species represented will strike you as amazing.

Central Kalahari Game Reserve

Covering about 52,800km², the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (or the CKGR, as it’s usually known) is one of the world’s largest game reserves. It dominates the centre of Botswana, the wider region that referred to here as simply the ‘Central Kalahari’. This is Africa at its most remote and esoteric: a vast sandsheet punctuated by a few huge open plains, occasional salt pans and the fossil remains of ancient riverbeds.

The CKGR isn’t for everybody. The game is often sparse and can seem limited, with only occasional elephants and no buffalo; the distances are huge, along bush tracks of variable quality; and until 2009, the facilities were limited to a handful of campsites. So without a fully equipped vehicle (preferably two) and lots of bush experience, it was probably not the place for you. The converse is that if you’ve already experienced enough of Africa to love the feeling of space and the sheer freedom of real wilderness areas, then this reserve is completely magical; it’s the ultimate wilderness destination.

In a change of policy, the authorities have permitted the establishment of two small lodges within the reserve, thus opening it up to those who don’t have the experience, the time or the equipment to come here alone. As a middle ground, there are also a number of mobile safaris operating in the area.

Almost parallel to the Okavango, the Kwando River flows south from Angola across the Caprivi Strip and into Botswana. Like the Okavango, it starts spreading out over the Kalahari’s sands, forming the Linyanti Swamps. Also like the Okavango, in wetter years this is a delta, complete with a myriad of waterways linking lagoons: a refuge for much wildlife. It’s a wild area, much of which is on the Namibian side of the border, in the Mamili National Park, where it’s difficult to access.

Both the Kwando and the Linyanti rivers are permanent, so for the animals in Chobe and northern Botswana they are valuable sources of water. Like the Chobe and Okavango, they have become the ultimate destination for migrations from the drier areas across northern Botswana – and also sought-after safari destinations, especially in the dry season.

All year round you’re likely to see impala, kudu, giraffe, reedbuck, steenbok, warthog, baboon and vervet monkeys throughout the area. Lion and spotted hyena are common, and generally the dominant predators, whilst leopard are often seen in the riparian forest and can be the highlight of night drives.

Cheetah occur, but not very frequently, and may have moved out of the area. Wild dog usually stay near their dens from around June to September (with July and August being the most reliable time for them), and then range widely over most of northern Botswana.

Blue wildebeest and Burchell’s zebra are present all year, although around May they will arrive in larger numbers, remaining within reach of the water until just before the rains begin in around November–December, when they head off southeast towards Savuti Marsh. Elephants and buffalo follow a similar pattern, with small groups around all year, often only bulls, but with much larger breeding herds arriving in June–July and staying until December. During this time you’ll regularly find very large herds of both buffalo and elephant, hundreds strong.

Okavango Delta

In his book, Lake Ngami and the River Okavango, the Victorian-era explorer and trader Charles John Andersson wrote:

On every side as far as the eye could see, lay stretched a sea of fresh water, in many places concealed from sight by a covering of reeds and rushes of every shade and hue; whilst numerous islands, spread over its whole surface, and adorned with rich vegetation, gave to the whole an indescribably beautiful appearance.

For modern visitors the Okavango Delta has lost none of its beauty. However, finding reliable information on the various areas from brochures can be as challenging as Andersson’s expedition.

When and how to visit

The best times to visit are dependent upon how you intend to visit, exactly which camps you are visiting, and why.

Flying in

If you’re flying into a camp in Moremi or the Delta then the season won’t make much difference to the access. The Okavango’s camps used to close down during January and February, but now most keep open throughout the year, despite being much quieter during the green season (December to March).

In terms of vehicle access to the various game-viewing areas from your camp, the rains are often less of a concern than the flood, the peak of which usually lags behind the rains by several months (depending on how far up the Delta you are). However, generally there will be the most dry land from about August to January.

Driving in

If you’re driving yourself into Moremi, it’s important to understand that only a restricted area of the reserve will be accessible to you, and the wet season will make this access even more difficult. As the rains continue, their cumulative effect is to make many of the roads on the Mopane Tongue much more difficult to pass, while it simply submerges others. Thus only the experienced and well equipped need even think about driving anywhere through Moremi between about January and April.

Most visitors who drive themselves come to Moremi in the dry season, between around May and October. Then the tracks become increasingly less difficult to navigate, although even then there are always watercourses to cross. As with all national parks, the speed limit in the park is 40km/h, with no vehicles allowed on the roads between sunset and sunrise.

Activities

The water levels will affect the activities that you can do whilst here. In some areas mokoro trips are possible only for a few months every year, when water levels are high enough. Similarly, the game drives from a few of the camps are generally possible only when water levels are low enough.

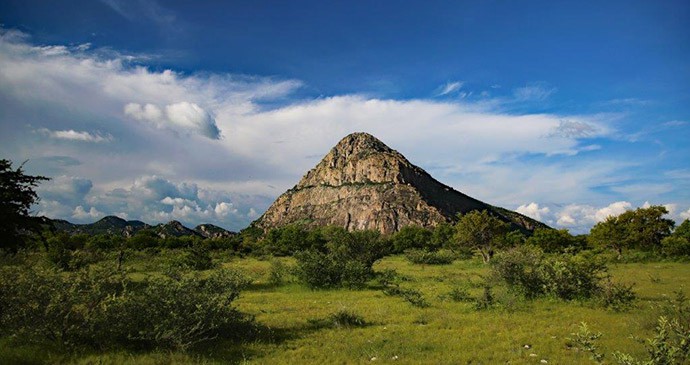

The Tsodilo Hills

Rising to 400m above the bush-covered undulations of the western Kalahari, the Tsodilo Hills consist of four hills, roughly in a line, with names from San folklore: the Male Hill, the Female Hill, the Child Hill and a smaller unnamed kopje. Highest is the Male Hill, rising to 410m above the surrounding bush, and – at over 1,400m in total – often considered to be the highest point in Botswana. The San believe that the most sacred place in the hills is near the top. Their tradition is that the first spirit knelt on this hill to pray after creating the world, and that you can still see the impression of his knees in the rock there.

The Female Hill, which covers almost three times the area of the Male, is a little to its north, but reaches only about 300m above the plain. This is where most of the main rock art sites can be seen. Then there’s the Child Hill, 2km further north again, and smaller still at only about 40m high. And another 2.2km northwest of the Child is a yet-smaller kopje that is said by the San to be the first wife of the Male Hill, who was then left when he met the Female Hill.

Archaeologists say that the hills have been sporadically inhabited for about 60,000 years – making this one of the world’s oldest historical sites.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Botswana:

Related articles

We’ve scoured the African continent for the best sites to spot rhinos in the wild.

From Botswana to Brazil, we’ve picked our favourite wetlands from around the globe.

Author Chris McIntyre looks at the most studied social group on the planet.