The mood is unmistakably caboverdiana, the unique, united identity of a country with a big heart and a deep soul.

Aisling Irwin, Colum Wilson and Murray Stewart, authors of Cape Verde: the Bradt Guide

Cape Verde survived a bout of being overhyped as the ‘new Caribbean’ a few years ago, but this diverse archipelago of nine inhabited and one uninhabited islands has settled back in to just being … itself. Discover for yourself the true Cape Verde – come for the music: mournful, frenetic or sexy in its various guises; come for the dazzling, white-sand beaches of Sal, Boavista or Maio; come for Fogo’s simmering volcano; come and hike the lush ribeiras and stunning, jagged peaks of Santo Antão or São Nicolau. Party hard at São Vicente’s boisterous carnival, enjoy a little bit of everything on Santiago – the ‘most African island’ – or escape from the world in tiny, rugged, isolated Brava.

If you’re stuck out in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, you need to be special to attract attention. Cape Verde is in the mid-Atlantic. Cape Verde is special and is, once again, attracting attention. Here, you’ll find a safe, welcoming and peaceful part of Africa that intriguingly defies any neat description.

At times, it doesn’t even feel African, a melting-pot of influences which draws on its Portuguese colonial days, a hint of Brazilian, a strong attachment to the United States and a dash of yes, the Caribbean.

But the mood is unmistakably caboverdiana, the unique, united identity of a country with a big heart and a deep soul. Cape Verde’s music is the key to unlock both: in a land where the language of the street is creole, with no written tradition, music is how Cape Verde expresses itself internally and impresses others internationally.

But don’t dwell too long on your reason for visiting Cape Verde; just make sure that you do visit, soon.

For more information, check out our guide to Cape Verde:

Food and drink in Cape Verde

Fish lovers will be in heaven on Cape Verde. The grilled lobster is superb, as are the fresh tuna, octopus and a multitude of other delicacies. The only disappointment sometimes is that no-one seems to have invented any exciting sauces or variations to liven up these freshly caught delights. Vegetarians may find only omelette on the menu but can always ask for a plate of rice and beans.

A Cape Verdean speciality is cachupa, a delicious, hearty dish that comes in two varieties: poor-man’s cachupa (boiled maize, beans, herbs, cassava, sweet potato) and rich-man’s cachupa (the same but with chicken and other meat). Cachupa takes a long time to prepare: some restaurants put a sign in their windows to indicate when they will next be serving it. Cachupa grelhada is perhaps the most palatable – everything available all fried up together, often for breakfast and recommended, especially when served with a fried egg on top.

An oddity of Cape Verdean restaurants is the apparent default setting of serving your chosen dish with rice and potatoes of some variety (chipped, boiled). For many, this is too much stodge, but you may have to be insistent to avoid it happening!

Another minor frustration can be the opening times. The situation has improved markedly, but there is still a fairly laid-back attitude to opening times, one which you may choose to adopt. Experience shows that some establishments do not publicise their opening times, or will not stick to them! On Sal and Boavista, this is less of a problem.

Local specialities are the jams (doce) and semi-dried fruits. These are often served as desserts along with fresh goat’s cheese, making a delicious end to the meal.

Most towns will have local eateries where huge platefuls of rice, chips, beans and fish, or of cachupa, are served up at lunchtimes for 300–600$, but these places may not be open all day. Look out for restaurants offering pratos do dia, often at lunchtime. These ‘dishes of the day’ give you a chance to fill up very cheaply, usually for around 400$ or less. Restaurant prices are defined in the rest of this book by the average cost of a main meat or fish dish.

In most places, these go for between 600$ and 1,200$. Lobster tends to be 1,800$ on some islands, but costs much more on Sal and Boavista. Tea is typically 100$ per cup; coffee the same, however, getting a decent tea or coffee can at times be difficult. Asking for tea can quite often bring an infusion of camomile or blackberry, so bringing a few of your favourite teabags from home is not a bad idea, if it’s important to you. Cha pretais black tea. The best coffee seems to be available from the larger airport cafés and ferry terminals, or from various Italian establishments on Sal and Boavista.

Food on the streets is fine, if unexciting. A good tip to finding it is to look near to the town’s market, if it has one. Th ere are many women with trays of sweets, monkey nuts, sugared peanuts and popcorn and tiny impromptu barbecues are also set up. Sometimes they will have little pastéis (fish pastries). The confectionery is very sugary, and flavours are mainly coconut, peanut and papaya. Here and there ladies fry moreia – moray eel. Nice, but greasy – just spit the bones out; the dogs will get them.

Cheap picnic lunches can be bought from supermarkets, markets and from bakeries. These exist in every town but they can be hard to track down, due to a dearth of signage. Ask for the minimercado if you get stuck and don’t be too choosy: often they are more mini than mercado.

Outside the big towns, try to call in at your chosen restaurant about 2 hours in advance to order your meal or you may well be restricted to the dish of the day.

Many remote villages have no eating places, but somewhere there will be a shop – often hard to distinguish from an ordinary house. There you can buy biscuits and drinks.

Bottled water is widely available and in ordinary shops is cheap (80$ for a 1.5-litre bottle, less in supermarkets); prices are inflated at hotels (up to 180$). Some of the wine made on Fogo island is distinctive and very quaffable and can be found for sale around the archipelago. Other wines tend to be imported from Portugal or Italy. There are three principal beers. Strela is a domestic brand, brewed in Praia, and has a sub-brand, Strela Ego, which is a high-strength lager (8%). The two brands imported from Portugal are the maltier Superbock and the less-common Sagres. Costs are typically 100$ for local and Portuguese beer and 250$ for other imported brands. On Sal many more familiar brands of imported drink are available, but are usually quite expensive.

The drink that Cape Verdeans literally live and die for is grogue. It is locally produced and abundantly available – in any dwelling carrying a sign above its door prohibiting children under 18 from entering.

On quieter islands such as Maio and São Nicolau, food shops and restaurants may open erratically and only for short periods. To avoid hours of hunger, always have provisions with you.

Travel and visas in Cape Verde

Visas

Every non-Cape Verdean visitor needs a visa unless they are married to, or are the offspring of, a Cape Verdean citizen – in which case they need their marriage or birth certificate. If there is a Cape Verdean embassy in your country you can obtain the visa from there. The cost varies from country to country.

In the UK, where there is no embassy, you have options. Whoever books your air tickets in the UK will probably be able to arrange the visa for you, to be picked up at the airport on arrival. (For those on package holidays, the cost of the visa is usually included in the package cost, but do check. You simply have to provide the tour operator with all your details in advance and you will have no delays on arrival in Cape Verde.

For independent travellers from the UK who want to get their visa in advance of departure, you can contact the Honorary Consul in London. If you need your visa in a hurry, a personal appointment can be made and the visa issued on the spot. A cheaper option for independent travellers is to simply arrive without a visa and just buy one at your arrival airport in Cape Verde. This costs €25, so is usually cheaper than the other options and is a straightforward operation. Note that it is payable in euros, so make sure that you have enough handy to pay for it. You will generally be given a visa for 30 days as this is the norm, but make sure you ask for the length of time you need.

You can extend your visa at the Direção de Emigrantes e Fronteras during your stay (you will need a passport photo, proof of funds, copy of return flight ticket, occasionally a fair degree of persistence, patience and to pay around 2,500$) and it is much easier to do this before your visa expires. They have offices in Praia, Mindelo (notoriously difficult), Sal and Boavista and the local police will direct you to the office. Fines are often levied on departure if you have overstayed, and are around €100. Visas bought in advance are normally also valid for 30 days.

You are not usually required to show proof of a return ticket to purchase a visa on arrival or to arrange a visa in the UK, but some other consulates (such as the one in Italy) will insist on it. All incoming passengers have to complete an embarkation form which is handed out on the plane pre-arrival. The visa form itself is available at the arrival airport.

Getting there and away

By air

Always bear in mind that the airline industry is a fluid one and the services detailed below may change, sometimes from month to month. There are international airports on Sal, Santiago, Boavista and São Vicente. Most international flights land at Sal; however, there is increasing traffic into the other airports. As internal flights are a little unreliable, it can be an advantage to fly to the airport closest to the island of your holiday destination. For example, travellers making for Santo Antão will have a much shorter onward journey if they fly directly to São Vicente, while those heading for Fogo should choose Santiago.

Scheduled airlines flying to Cape Verde include TAP Portugal, the national carrier TACV, Transavia, Bintercanarias, Senegal Airlines, Royal Air Maroc and TAAG Angola. TACV has been subject to an enormous amount of disruption and although its safety record is exemplary it cannot be recommended as an international link, because of its unreliability. You should, however, check whether the situation has improved. Charter flights come and go. Thomson and Thomas Cook (from the UK), TUIfly (from Germany), TUI Nordic (from Scandinavia) and Jetair (from Belgium) are some of those who operate charter flights to Cape Verde from Europe. Direct flights from Europe range from around 6 hours, from the north, to 3 hours from southern countries such as Portugal.

Note that a domestic airpass giving fixed prices on inter-island flights was previously available, but only to tour operators booking international flights to Cape Verde with TACV. It’s worth asking your tour operator in case it is revived.

By sea

Arriving by sea and watching the Atlantic crags materialise from the ocean is an unusual and uplifting way of reaching the islands. Some ships stay for 48 hours, which is plenty of time in which to get across from Mindelo to see the highlights of Santo Antão. An increasing number of cruises are stopping in Cape Verde, mostly in Mindelo. These include Cunard , P&O, and Celebrity Cruises. Smaller cruise ships, such as the Marco Polo, sometimes go to Fogo. Noble Caledonia are now offering cruises which involve ‘island-hopping’ tours to seven islands in the archipelago.

Getting around

By air

The simplest, most convenient, most comfortable, as well as the most reliable way to travel between the islands, is to fly. Anyone with only two weeks in the archipelago should not consider taking a ferry, though there is no alternative to get to Santo Antão or Brava, neither of which has a functioning airport.

Since the demise a few years ago of their only competitor, Halcyonair, the only practical option for inter-island flights has been the national airline, TACV. But in late 2016, after many rumours and regulatory hiccups, Bintercanarias launched inter-island flights in Cape Verde in competition to TACV. New, logo-ed offices have appeared in the airports in Sal, Praia and São Vicente, and a new website specific to the company’s Cape Verdean inter-island service has been created. It is certainly worth monitoring this site (www.binter.cv) as the company to São Vicente and Praia to São Vicente.

Flights with TACV cost from €30 per single journey for a short hop (from Sal to Boavista, for example) to more than double that for longer flights. Journeys take between 20 minutes and 50 minutes. Baggage allowance in economy class for internal flights is 20kg, hand luggage is limited to a stingy 5kg. Bintercanarias allow you 6kg of hand luggage and their flight prices are comparable on the routes they service.

If you are on a very tight schedule or know exactly what you want to do, it is better to book internal flights before you go. If you leave it until you arrive you may not get the flight of your choice although there may be other options if you are flexible. At certain times of the year (festivals or times when emigrants arrive for their holidays), fl ights get very busy – it may therefore be worth checking with a local travel agent. Flights are generally cheaper the further ahead you book and there are sometimes promotional fares.

Cabo Verde Express operates charter day trips, in general from Sal and Boavista to Fogo. Unless you are planning to charter a whole plane (!), you will need to sign on to a group tour via one of the operators, who advertise everywhere in Sal. You can book a flight-only option if there is availability but this is only possible at the last minute.

By ferry

These are not the Greek islands; we are in the middle of rough Atlantic waters with great distances between many centres. To reach airport-less Brava or Santo Antão, you have to take a ferry. For other inter-island journeys, ferry trips are difficult to recommend on grounds of comfort and even safety.

If you are hyper-adventurous, or even reckless, ferries do operate between many of the islands, although journey times on potentially rough seas are long and schedules are not always strictly adhered to, so it is essential to double-check the sailing times listed throughout the guide. This website keeps reasonably abreast of the ferry situations. In 2008, two ferries sank and before that, two newly introduced catamarans were withdrawn because they couldn’t cope with the rough seas. In 2015, there was a tragic ferry sinking off Fogo, with 11 lives lost. Single journeys cost between €8 and €40, depending on the distance. You are unlikely to find a ferry too full to take you, except at Christmas time, but boats can be delayed for days and journeys are long (up to 14 hours!). The services between Fogo and Brava, and between Mindelo on São Vicente and Porto Novo on Santo Antão, however, are more reliable and enjoy a much shorter journey-time, around 40 minutes and 1 hour respectively.

Cabo Verde Fast Ferry (CV Fast Ferry started operations in 2011 with an initial route linking the southerly islands of Santiago, Fogo and Brava. The long-promised arrival of a second ferry has eventually materialised, but one or other vessel seems to be constantly under repair. These custom-built ferries are more modern and comfortable than the others and have improved the reliability of interisland travel. Single fares are around €14 between Fogo and Brava, and €35 between Santiago and Fogo. Their Facebook page also contains updates (cvfastferry). Always book in advance, as ferries do not sell tickets on board, and take your passport to the office when booking.

By yacht and catamaran

There are day trips from Sal to Boavista in various different craft. There are also yachts available for charter between the islands.

By bus

Outside of Praia and Mindelo (where city buses operate), hiace minibuses and open trucks with seating in the back (Hiluxes) constitute the public transport. They are recognisable by the sign ‘aluguer’ and on most islands that is what they are called, though on Santiago the preferred term is hiace (pronounced ‘yazz’). They are typical African transport, often overloaded with people, chickens and packages and trundling along to the sound of happy-go-lucky tinkling music.

Generally, alugueres converge at a point in a town or village which anyone can point out to you; often they drive around picking up passengers and few leave town before they are full. You shout (‘para!’ which means ‘stop!’) when you want to get off and you pay after disembarking. Alugueres can be flagged down anywhere along the roads. In Cape Verde, unusually for West Africa, many of these vehicles are in good condition and consequently most of their drivers are careful and reasonably slow.

The great disadvantage for visitors can be the timings of the alugueres. Often they seem to leave outlying villages at 05.00 or 06.00 to take people to town, much to the bewilderment of the visitor. They then leave town for the outlying villages between 11.00 and mid afternoon. Time and time again tourists pile into the 11.00 aluguer only to find they have no way of getting back to town in the evening without chartering a vehicle at ten times the price.

By taxi

The term ‘taxi’ refers both to the cars with meters and taxi signs, found in towns, and to hiaces that have been chartered by an individual. Chartering costs about ten times the public fare and you may be forced to do it if you want to go somewhere at a different time of day from everyone else. Sometimes the fares for a charter can be bargained down and occasionally an opportunist will try to diddle you, but generally charter prices are fixed – they’re just comparatively high. Drivers in general love to be chartered by a tourist so watch out when they tell you there is no more public transport that day – hang around to check and insist that you want to travel colectivo, but also accept the possibility that they might actually be telling the truth! Tourists often get together to share a chartered minibus. Note that taxis after dark attract a premium of around 25%.

By car rental

This is possible through local chain firms on São Vicente, Sal and Santiago and there are tiny firms on some of the other islands. International firms have opened on Sal and Santiago. For contact details see the relevant island chapters. Book several days ahead if you can and don’t expect things to run smoothly – for example, the wrong car might arrive several hours late with no price reduction offered for the inconvenience. Car maintenance standards do not match those you might find in western Europe or North America.

By cycling

Keen cyclists do take their bicycles to the archipelago and return having had a good time. Bicycles can be transported between the islands on the larger TACV 46-seater planes. You pay by weight, just as with other baggage, so carriage is free if it falls within your luggage allowance. Bicycles may also be hired on Sal, Boavista, Maio and Santo Antão.

When to visit Cape Verde

The islands are warm and sunny all year round so for many visitors without any special interests, it doesn’t really matter when they go. For windsurfers the best months are January and February while divers will find the calmest waters and peak visibility from June to December; beach lovers might wish to avoid the windy winter months. Fishermen after marlin should opt for May to October, while tuna fishing is at its best in August. For hikers, the mountainous islands are significantly more beautiful during and just after the rainy season of July to December, though flooding can impede some Santo Antão hikes. The heaviest rainfall is usually in August and September. For those concerned about the heat, the peak is in September (with an average daily temperature of 30°C), with the trough being in January (average 24°C).

For those who wish to see nesting turtles the season is June to October, peaking in mid-July and August. Turtle hatchlings are born from mid-August until the end of November. Whale-watchers will find the best opportunities in March and April, particularly off Boavista. Photographers should avoid December to March when the harmattan winds dull the light, and leave deposits of sand. Party animals and music lovers might choose February for the São Vicente Carnival, or for that in São Nicolau; August for the São Vicente Baía das Gatas music festival; or May for the Gamboa music festival in Santiago. To coincide your visit with one of the more low-key festivals, consult the individual island chapters. Those on a tight budget will find hotels cheaper from April to June and in October, and should definitely avoid Christmas and Carnival time. Peace seekers might avoid July and August, when Cape Verde is full of both European holidaymakers and emigrante families taking their summer holidays back home. As well as Christmas and Carnival times, the whole period from November to March is high season.

Climate

Caught in the Sahel zone, Cape Verde is really a marine extension of the Sahara. The northeast tradewind is responsible for much of its climate. It blows down particularly strongly from December to April, carrying so little moisture that only peaks of 600m or more can tease out any rain. The high peaks, particularly on Fogo, Santo Antão and Brava, can spend much of the year with their heads in the clouds.

Added to that wind are two other atmospheric factors. First is the harmattan – dry, hot winds from the Sahara that arrive in a series of blasts from October to June, laden with brown dust which fills the air like smog. The second factor is the southwest monsoon, which brings the longed-for rains between August and October. Often half the year’s rainfall can tumble down in a single storm or series of storms. Unfortunately Cape Verde’s position is a little too far north for the rains to be guaranteed each year: it lies just above the doldrums, the place where the northeast and southwest tradewinds meet and where there is guaranteed rainfall.

What to see and do in Cape Verde

Brava

Brava is the most secret of the islands – a volcano crater hides its town, rough seas encircle it and the winds that buffet it are so strong that its airport has been closed for years. Brava lies only 20km from its big brother, Fogo, but many visitors to Cape Verde will merely glimpse it from the greater island’s western slopes.

Brava – or ‘wild’ island – appears at first to live up to the meaning of its name. Approaching by boat, the dark mass resolves itself into sheer cliffs with painted houses dotting the heights above. A few fishing hamlets huddle at sea level.

But its unpromising slopes hide a hinterland that is at times fertile and moist, filled with hibiscus flowers and cultivation. At least that is how it was: today, after years of drought, its flowers are less visible and its food more likely to be imported than grown.

This tiny, westerly island, dropping off the end of the archipelago into the Atlantic, seems to hide from its companions and look instead towards where the sun sets – it is dreaming of the wealth of the USA. Perhaps that is no surprise. For Brava is the island where the great 19th-century American whaling ships called to pick up crews and spirit hopeful young men away to new lives in another continent. The legacy is an island full of empty houses waiting for the return of the Americanos who have built them for their retirement.

Cidade Velha

This once-proud town, formerly known as Ribeira Grande, has had nearly 300 years to decay since the French robbed it of its wealth in 1712. Now there is just an ordinary village population living amongst the ruins of numerous churches, the great and useless fort watching over them from a hill behind. Its inhabitants are still poor but there have been efforts to develop some tourist potential in town and it is becoming a delightful place, with cafés on the shore, bright fishing boats in the harbour and a tourist information office, albeit one that is very shy about opening. It is magical to wander through the vegetation in the ribeira and in the surrounding hills to discover the ruins of what was once a pivot of the Portuguese Empire. It’s popular as a Sunday destination for city dwellers.

Maio

Maio was, and some would say still is, the forgotten island. Its quiet dunes and secret beaches have been overshadowed by the more boisterous Sal and beguiling Boavista. It has been waiting to be thrust into the tourist mainstream, and fleetingly it seemed that its time had come. But plans for a massive increase in accommodation have, at least for now, been thwarted and development projects stand gathering dust. How the transport and other infrastructure were ever intended to keep pace is unclear. For many, this is a blessing, as it leaves undisturbed this island backwater. With uncertainty over Maio’s future as a mass-market destination, restaurants and tourism-related businesses are susceptible to frequent changes of ownership and closure.

Visitor footfall is light. Those who live on Maio or visit it frequently justifiably claim that the island is overlooked in other ways. Flight times are often changed, cargo boats fail to materialise and as a consequence, the shops sometimes run short of supplies. But visitors may revel in the authentic feel that Maio possesses, the genuineness of the island and the seemingly gentle and welcome indifference of the inhabitants to grabbing hold of your hard-earned holiday spending money.

Mindelo

The wide streets, cobbled squares and 19th-century European architecture all contribute to the sense of colonial history in Mindelo. Most facilities lie not on the coastal road but on the next road back, which at the market end is called Rua de Santo António and, after being bisected by the Rua Libertadores d’Africa (also known as Rua de Lisboa), becomes Avenida 5 de Julho. Most road names in the centre of town have changed, but many of the old signs linger and firms vary as to which street name they use. Like most towns in Cape Verde, street names are of limited use, and mentioning them when talking to locals will often draw a blank stare!

Monte Gordo National Park

Although there are 47 protected areas in Cape Verde, enshrined in law, all but Monte Gordo have an Achilles heel: their precise, mapped boundaries have not been legalised. This leaves them vulnerable. In Boavista, for example, there are several areas where land originally allocated for protection has been reallocated for tourism development instead.

In São Nicolau, however, the boundaries of its beautiful heart were officialised in 2007. Much work has been done and more is still underway to create a park that is pleasant for tourists and might enhance the prosperity of the people who live there.

It’s an important area ecologically because of its rich biodiversity. The unique conditions that have generated this interesting ecology set it apart, not just from the rest of the island but also from the rest of Cape Verde. At the heart of these differences is climate, which affects not just life in the area but also landscape. In the south and southeast there are humid and semi-humid regions. In the north and northwest it is arid.

A key aim of the park is to develop a thriving local economy predicated on conservation of the area: over 2,000 people live within the park boundaries. This is why a lot of thought has gone into training guides (who are salaried), and training local people to be useful to visitors, for example by making handicrafts. There is a good park office where you can get information and purchase handicrafts made exclusively on the island. The park certainly has potential, yet to be fulfilled.

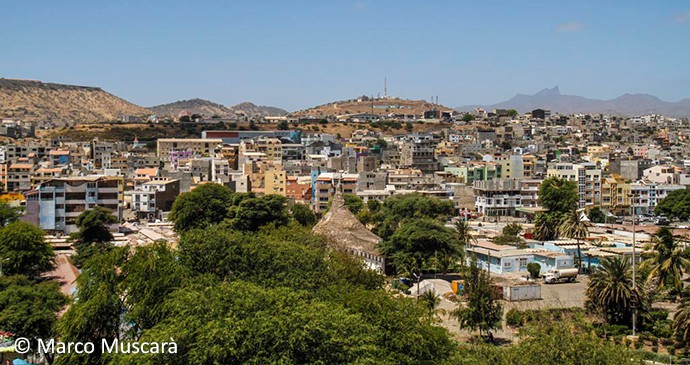

Praia

Built on a tableland of rock, with the city overflowing on to the land below its steep cliffs, the centre of Praia – its Plateau – is attractive. It has a disorientating feel: it is indisputably African and yet Mediterranean as well.

Praia continues its rapid growth and the current estimated population is in excess of 130,000. Infrastructure – from sewage treatment to electricity generation – is finding it impossible to keep pace with this chaotic expansion. Journey to the outskirts of Palmarejo, where there is frenetic building, and you will see an entire hill being gradually, and illegally, hand-mined away. Some of the miners live in little caves in the hillside.

During the day, people of every shade of skin go about their business on the Plateau. At night, and on Sunday mornings, though, the Plateau is empty – life continues in the scattered regions beyond. To its south rises another level plain, the Achada Santo António, where the more affluent live in apartment blocks and where you’ll find the huge parliament building. Between the two lies Chã de Areia, and, in front of Achada, Prainha, where there are embassies, expensive hotels and nightclubs.

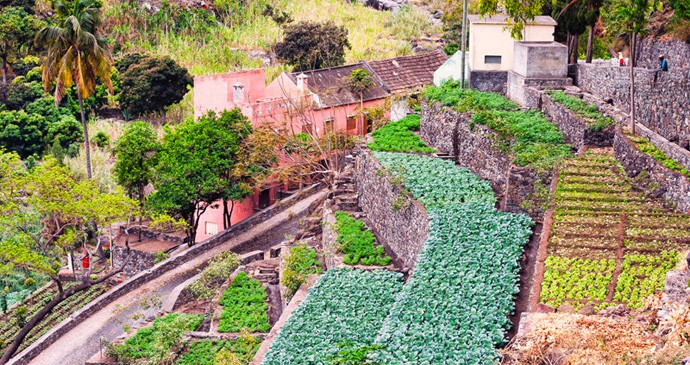

Ribeira do Paúl

A vast ribeira home to thousands of people and their agriculture – sugarcane, breadfruit and bananas – Paúl is renowned throughout the archipelago for its grogue, and one of its trapiches (sugarcanejuicing apparatus) is still driven by oxen. Highlights include Passagem, with its charming municipal park nestled among impressive almond trees and bougainvilleas. Beyond the villages of Lombinho and Cabo de Ribeira, up a steep incline, a panoramic view of the valley and ocean opens out. The road ends at Cabo de Ribeira, but a steep cobbled footpath continues to Cova, an impressive ancient crater now filled with verdant cultivation. Walk up or down, depending on your fitness and appetite for climbing; there are plenty of little shops and a few restaurants en route.

Santa Mónica Beach

This beach is well worth a visit, but do come prepared, particularly if you are walking. You will need food, suncream and loads of water. In a 4×4, follow the road through Povoação Velha. After 6km a very rough track deposits you on the beach, named after the famous Californian strand. The Boavistan version is undeniably magnificent but a good deal bleaker. Swimming is possible here because of its southern aspect.

Serra Malagueta

Situated in northern-central Santiago, Serra Malagueta is an important area ecologically and one of the last remaining forest resources on Santiago. It is the starting point for some classic Santiago hikes.

The heart of the area is now a natural park, which spans 774ha and reaches a height of 1,064m at the peak of Monte Malagueta. The park houses important threatened and endemic species. There is even one local endemic, the carqueja de Santiago, a small shrub that lives between 500m and 800m. The ecotourist facilities offered are not quite as well advanced as those in Fogo or São Nicolau but there is a newly relocated centre and the management has created a campsite and marked out (on a map and information boards) some suggested hikes covering in total 55km and with a wide range of difficulty and duration.

While hiking in the area, watch out for vervet monkeys and for the rare endemic Cape Verde purple heron or garça vermelha (Ardea purpurea bournei), which can be seen here in the trees near the Centro Ambiental. Santiago is its only home.

Tarrafal de Monte Trigo

This isolated spot on the west coast is hard to get to but definitely worth the effort. The road up, then down, from Porto Novo is spectacular, with breathtaking views over to São Vicente, Santa Luzia, São Nicolau and even Fogo, on a very clear day. It may not be passable in the rainy season, as bridges can be washed away. Your aluguer driver will probably stop if you want to take photos – and you undoubtedly will. The approach from the sea is also beautiful – a small spot of green colour amongst the brown-grey massifs of the mountains gradually resolves itself into the whites and pastels of this sleepy town. Around the black-sand shore – the longest stretch of beach in Santo Antão – fishermen relax, fierce games of oril click away under the trees, women wash clothes; and hens, pigs, goats and dogs go purposefully about their business.

Sea eagles are common here, so keep an eye open for them plucking their dinner from the ocean. This a great venue in which to do very little, a perfect place to relax at the beginning or end of a hiking holiday. Snorkelling and scuba diving are both possibilities, as is fishing with the locals. In the last few years, this sleepy backwater has begun to waken itself. Electricity is now available all day, mobile-phone coverage has arrived and Wi-Fi is available in some of the guesthouses. Further improvements to the infrastructure are underway, for better or worse.

Ponta Preta

A stunning beach with a single restaurant from which to appreciate it, Ponta Preta is a favourite of windsurfers and surfers. It is possible to reach the beach by walking for about an hour around the coast from Santa Maria. Alternatively, drive along the road that goes west from Santa Maria towards the resort hotels, turn right opposite Hotel Crioula and go straight ahead for approximately 2km. You will see, after a few minutes, the timber-built restaurant, and a minute after that you will find a rough track leading towards the water.

There is also a little wooden hut, where a man can be seen making handicrafts from fish bones and sandstone. (Some of his other products are imported from mainland West Africa.) Just north of Ponta Preta the Melia Group have a host of all-inclusive hotels on and around Algodoeiro Beach; the Melia Tortuga is home to Cabo Verde.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Cape Verde:

Related articles

Author Murray Stewart talks about his time in Cape Verde and explains why it’s worth a visit.