‘This is Africa’ is a phrase that comes to mind often in Sudan: the epic scale of the Sahara, seen from the air as you fly into Khartoum or felt rather closer to hand with the grit in your face as you drive through northern Sudan, takes your breath away just as the endless savanna does in the Dinder National Park.

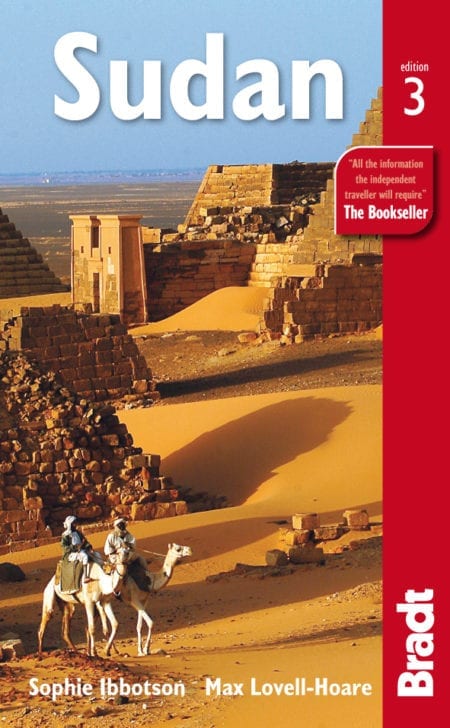

Sophie Ibbotson and Max Lovell-Hoare

As a staple of bleak news headlines, Sudan has been slow to make its abundant attractions known to the outside world. It is we who are losing out.

Few foreigners have heard of the ancient Kingdom of Kush, walked among the isolated pyramids of Meroë (far more numerous and yet less crowded than those in neighbouring Egypt) or witnessed entranced the whirling Sufi dervishes of Omdurman. Yet those who do make it here are invariably enchanted by Sudan’s easy-going nature, its varied, fascinating history and the warm welcome they receive unexpectedly from the Sudanese people.

The country has an incredible variety to offer the intrepid traveller, whether you are coming for the first time or returning after many years. From the labyrinthine souks of old Khartoum to the coral-bedecked wrecks off the Red Sea coast, this is an unpolished tourist offering, and one that enables you to look deep into Sudan’s culture past and present.

Whether you’re rushing through on the trans-Africa trail or whiling away weeks among rich archaeological sites, Sudan will certainly not disappoint. By all means tick off the advertised highlights of Omdurman, Meroë and Suakin, but also take the time to make your own discoveries, meet people and soak up the experience.

For more information, check out our guide to Sudan

Food and drink in Sudan

Sudanese food is uncomplicated. It is based around a few staples with spices used only sparingly. Some people complain of bland repetition, but it is possible to eat a good and varied diet on the road. Many of Sudan’s staples are vegetarian, although travellers should be aware that some dishes such as stewed vegetables often use meat stock as flavouring, or are cooked with a few small pieces of meat lurking in the pot. Most restaurants are of the cafeteria variety, with the kitchen and food on display at the front. With no menu to consult you’ll need to poke around the pots to see what’s on offer. Cutlery isn’t used so you eat with your right hand, using bread as a scoop. Most cafeterias open in the morning in time for breakfast – the most important meal of the day in Sudan – which is taken any time between 09.00 and 11.00.

Food

Sudan’s favourite dish is ful, brown beans stewed for hours in a large metal cauldron (gidra). The ful is ladled out into bowls, often mashed slightly and served with a generous squirt of oil (zeit), a sprinkling of spice, and a round of bread (kisra). At its simplest, ful can be pretty uninspiring, but it’s usually enlivened by adding salad (salata), cheese (jibneh), hard-boiled egg (bayda) or falafel (taamiya). Served this way a bowl of ful makes a delicious and filling meal.

In some places, a poor man’s ful is served using the bean water left over in the gidra, mopped up with bread and onions. This dish is called bush, as it derives from the shortages of the early 1990s when the first President Bush cut aid to Sudan in response to Sudanese government support for Saddam Hussein in the first Gulf War. Fasuliya is another bean dish, served in a tomato-based sauce – the Sudanese equivalent of baked beans. Yellow lentils are served as a thick broth, adis, which is often made in the mornings. Other vegetable dishes include stewed potatoes (batata), okra (baamiya), and peppers or aubergines (egg plant) stuffed with rice (maashi).

The most common meat dish is the kebab, although the meat is often tough and stringy. Kebabs are usually cooked on skewers, but one variety you’ll often see is sheya, where very fatty meat is cooked on flat stones sitting on a bed of charcoal. In large towns, Western-style fast-food joints serve shwarma kebabs from a vertical spit; these are most commonly lamb, but are occasionally chicken. The same places offer burgers in a bun, always with a fried egg on top. Kibda is fried chopped liver, a popular breakfast dish. A meat dish from western Sudan is agashay, where meat is flattened and breaded before being cooked over coals – a type of Sudanese schnitzel.

Along the Nile, fish (samak) is popular. Large fish such as Nile perch are filleted before being fried and are accompanied with bread and a fiery chilli dipping sauce (shotta). Smaller fish are cooked whole and it’s possible to spend as much time fishing for bones as meat. Many places cook their fish throughout the day, piling them up in a glass cabinet on the street for customers to choose from. For some reason, the taste for fish doesn’t extend greatly to the Red Sea, and good seafood can be difficult to find there.

Taamiya (the Sudanese version of falafel) is a popular street snack, although people used to the salad and yoghurt flat bread wraps from the Middle East might be disappointed. The chickpea balls are served dry in a bread roll with no accompaniment, or with a slice of tomato at best. Buy a bag from a stand and eat them on the move.

If you’re looking for dessert, the Sudanese love of sugar will provide. Every town has a sweet bakery, where you can splurge on cakes and pastries. The most popular is Middle Eastern-style baklawa, a super-sweet confection of pastry, honey and nuts. Zalabia, a deep-fried treat that’s similar to a doughnut, is made in the morning at tea shops as a light snack to tide people over until mid-morning breakfast.

Drink

Along with ful, Sudan runs on tea (shai) and coffee (gahwa). Tea houses tend to be dark and gloomy places, with a couple of old men invariably sucking on a water pipe. Far more common are the tea ladies you find on almost any street corner. These women run impromptu tea stalls consisting of little more than a brazier and a lockable chest covered in jars of tea, coffee and spices. Stools – or old cooking oil cans – provide the seating. They are a great place to watch the world go by over a drink, while the stallholder keeps court over a never-ending routine of kettle juggling, coffee pounding and fire stoking.

Different drinks are favoured throughout the day. Black tea (shai saada) can be drunk at any time, but drinking it with milk added (shai bi laban) is reserved for the early morning and evening. Hot milk (laban) is also popular and often flavoured with nutmeg. Tea is also made with mint (shai bi na’na’) and spices, most typically cloves (shai bi habahan). Whichever you choose, the tea is always served with a vast amount of sugar (sukar), although as a sop to Western sensibilities you’ll sometimes be asked if you want it without sugar (bidun sukar).

Coffee is made by simply boiling up grounds, and can be slightly gritty. A Sudanese variation sees the coffee flavoured with ginger or cinnamon and transferred to a long-stemmed pot and served in small china cups. The distinctive pots (jebana) give the drink its name. Finally the tea ladies may offer you karkaday, made from hibiscus flowers. It’s just as refreshing served cold.

Sudan abounds in fruit, and juice bars are deservedly popular. Availability varies, but some of the best are mango (manga), lemon (limoon), grapefruit (grebfrut) and occasionally banana (moz). Not to mention Sudan’s real treats which are raisin (za bid), baobab (tabaldi) and grewia tenax (godeam). A personal favourite is a mix of guava (guafa) and watermelon (batikh). A glass of cold juice can feel like the healthiest drink around, but be aware of the blocks of ice providing the cooling, as they are usually made from untreated water.

The usual international brands of fizzy drinks usually referred to as sodas are available everywhere in Sudan, along with a few homegrown varieties, like the fizzy apple-drink Stim, and Pasgianos, a sort of fizzy kardakay. Mineral water is also widely available, but in small remote towns it can be expensive. Reliable brands include Soba, Safia and Crystal. In Khartoum the water is generally safe to drink, although the tang of chlorine may put you off.

On any street in Sudan you will often see a couple of large earthenware pots on stands. Kept in the shade and covered, each pot (zir) is slightly porous – as water slowly seeps out it evaporates, keeping the contents cool for passers-by to refresh themselves. Whether or not you want to drink from the never-washed cup tied to the zir (and in some places the water can be distinctly murky) is up to you, but it’s a neat communal approach to drinking water in a hot country.

Alcohol is illegal in Sudan, a prohibition ignored by some. The most commonly encountered under-the-counter drink is araki, a lethal spirit made from dates that’s roughly akin to rocket fuel. In the west you may come across merissa, a beer brewed from sorghum. A non-alcoholic beer called Birell is available in large towns, although it hardly seems worth the effort.

You’ll often see Sudanese men producing a small pouch of indeterminate green material, rolling it into a ball and inserting it between the gum and lip. This is sa’oud, or snuff; it’s actually tobacco soaked in spiced water. The nicotine rush from sa’oud is very strong, but, if you do try it make sure you don’t swallow any of the juice or you’ll suffer the consequences. Do as everyone else does and expel a gob of fluorescent green spit every so often. A mellower experience can be had smoking the shisha (water pipe) over a drink in a tea house.

Health and safety in Sudan

Health

Travelling in the developing world presents different issues regarding health compared with Western countries. By taking sensible precautions you can greatly reduce your risk of catching any serious disease, and visitors to Sudan are unlikely to encounter any medical problem more acute than a bout of travellers’ diarrhoea. That said, you should seek up-to-date advice at least two months before travelling to ensure that you have all necessary immunisations and anti-malarial drugs before departure.

Immunisations

Hepatitis A vaccine (Havrix Monodose or Avaxim) comprises two injections given about a year apart, though you will have cover from the time of the first injection. The course typically costs £100 and, once complete, gives you protection for 25 years. The vaccine is sometimes available on the NHS. Hepatitis B vaccination should be considered for longer trips (two months or more) and by those working in a medical setting or with children. The vaccine schedule comprises three doses taken over a six-month period, but for those aged 16 or over it can be given over a period of 21 days. The rapid course needs to be boosted after one year. A combined hepatitis A and B vaccine, ‘Twinrix’, is available, though at least three doses are needed for it to be fully effective.

The newer, injectable typhoid vaccines (eg: Typhim Vi) last for three years and are about 85% effective. Oral capsules (such as Vivotif) may also be available for those aged six and over. Three capsules taken over five days last for approximately three years but may be less effective than the injectable version. Typhoid vaccines are particularly advised for those travelling in rural areas and when there may be difficulty in ensuring safe water supplies and food.

Meningitis vaccine (containing strains A, C, W and Y) is recommended for all travellers, especially for trips of more than four weeks. A single dose of the Meningitis Menveo vaccine costs around £65 and lasts for three years. It has the added advantage over the older polysaccharide vaccine of preventing nasal carriage and therefore transmission to family and friends on return. Rabies is prevalent across Sudan and vaccination is highly recommended, especially for those travelling more than 24 hours from medical help or who will be coming into contact with animals. Pre-exposure vaccination with three doses will remove the need for part of the post-exposure treatment which is expensive and unlikely to be found in Sudan. The pre-exposure course needs to be administered over a minimum of 21 days and will cost a total of around £50.

Proof of vaccination against yellow fever is needed for entry into Sudan if you are coming from another yellow fever endemic area. It is also recommended for travellers to areas south of the Sahara Desert where there is disease unless there is a specific contraindication to the vaccine. There is no risk in the city of Khartoum. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that this vaccine should be taken by those over nine months travelling to Sudan, although proof of vaccination is only officially required for those over one year of age. If the vaccine is not suitable for you, then you must obtain an exemption certificate from your GP or travel clinic or if the vaccine is needed because you are travelling to risk areas then you should consider not going as yellow fever can be fatal in the non-immune individual.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on www.istm.org. For other journey preparation information, consult www.travelhealthpro.org.uk (UK) or http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ (US). Information about various medications may be found on www.netdoctor.co.uk/travel. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Survival guides typically tell you what to do once you’re neck-deep in the brown stuff. This isn’t a smart position to be in. Avoiding getting into trouble in the first place is infinitely preferable.

Preparation is key. Using reliable information sources, establish where you’re going, how you’re going to get there, and how you’re going to get back. Always have a plan B. Tell this information to someone you trust. Keep your eyes and ears open and be flexible: choosing to change your plan in light of new information is much better than being forced to change it on the hop when circumstances conspire against you. Listen to your gut: evolution has given you the ‘hunch’ for a reason.

Gunfire and bombings

There is a general threat of terrorism in Sudan and both the government and foreign forces have been responsible for bomb attacks in the country in recent years. A US diplomat and embassy driver were shot dead in Khartoum in 2008, and the border with South Sudan is a known target for bombing raids purportedly targeted at militants but more often hitting civilians. Try to avoid drawing attention to yourself: don’t wear military-style clothing or anything that could be mistaken for uniform; avoid using a camera flash or any equipment that is especially shiny else it catch the light and be mistaken for a weapon firing; and consider carefully any markings on your vehicle. Words such as ‘Press’ and ‘UN’ can provide immunity but equally can make you a target.

If you are indoors and hear shots, remain in the building, lock the doors and stay away from windows. If there are a number of people inside, stay together as a group and raise the alarm by phone. If the firing comes closer, move into an internal room or under the stairs if possible. If you have time, place wet mattresses against the walls of the room you are in so as to absorb fragments of plaster and flying glass.

If you are caught outside, your first priority is to take cover. Don’t look for the person firing but move away from the sound. Keep your head down and find somewhere from where you can better assess the situation and your escape route. If you need to look out, look round not over the object you are hiding behind. Unlike in the movies, a car door will not protect you from bullets and you should avoid hiding behind a petrol tank: if it is hit it will explode. If a car is the only source of shelter, squat behind the engine block (located between the two front tyres). When you move, move individually rather than as a group and abandon any equipment that will slow your escape.

In the event of an explosion, take cover immediately. Drop to the floor if there is nothing to protect you as it reduces the likelihood of being hit by flying debris. Assess the situation and then, when it is safe to do so, move away from the sound of the bomb. Do not remain on the site, and do not stay with the crowd: there is always the threat of a second explosion.

Crowds, protests and riots

Demonstrations can occur at short notice in Khartoum and in Sudan’s other major cities and usually focus on economic or political concerns. Although they may appear peaceful there is no guarantee they will remain so, and government forces have been known to disperse crowds aggressively. The best advice is to avoid all street protest. There is no safety in numbers and even a benign-feeling crowd can swiftly attract a violent response.

If you are unavoidably caught in a riotous crowd, keep your head down and avoid confrontation. Look for a way out (even if it is into a neighbouring building) and avoid bottlenecks where there is a risk of being trampled. Remove or cover up any clothing that may be misconstrued as uniform; walk rather than run to avoid attracting unwanted attention; and remain inside your car if at all possible – it is safer to drive out than walk.

If you face armed riot forces (including police or government troops), try to get out of their way swiftly but without drawing unnecessary attention to yourself. Even if live rounds are not being fired, rubber bullets and water cannons can both cause serious injury and even death. If you cannot avoid being hit, stay low to the ground and roll into a ball with your back to the weapon. Keep your face covered with your arms.

Tear gas and pepper spray are commonly used to disperse rioters and they stick to everything. If hit, your skin and eyes will burn, your nose will run and your mouth will water. You may cough and feel incredibly dizzy. Try to keep your face covered – any scarf or item of clothing will help. If the fabric is soaked in water it will soak up some of the gas. Avoid rubbing your eyes or skin as it will make the pain worse.

The immediate effects of gas should wear off within an hour, but you still need to decontaminate your skin and clothing. You can create an effective decontaminant solution by diluting Alka-Seltzer, Pepto-Bismol, bicarbonate of soda or similar. Use it to flush your eyes, mouth and skin. Wash your hands and face as soon as possible in a detergent-free soap and change your clothes. If you were wearing contact lenses at the time of the attack, bin them and wear glasses for the next few days.

Kidnapping

The kidnapping of foreigners is an ongoing risk in Sudan, especially (though not exclusively) in Darfur. The victims have ranged from NGO workers to engineers, and it should be noted that it is British government policy not to make substantive concessions to hostage takers else this increases the risk of further hostage taking.

It goes without saying that you should try to avoid being kidnapped in the first place. Enlist someone with local know-how to help you make travel plans, avoid drawing attention to yourself and your possessions, and be aware of new people around you. Always let someone trustworthy know where you are going and when, and update them if your travel plans change.

If you are kidnapped, the experts advise that you accept your position as prisoner and act like one – do not behave aggressively, don’t make threats or promises, and do not draw attention to yourself if you are amongst a group. Do not escape unless you are certain that you can do so safely: you may be shot or put under closer watch, making it even more difficult for any rescuers to extract you subsequently.

Try to build a rapport with your captors: you want them to recognise you as an individual person, not as ‘the enemy’ or a commodity. Talk about your children (real or imaginary) and show them any pictures you have. Be polite and make an effort to communicate, even if you don’t share the same language. Make sure you eat whenever you are offered food, ask if you need first aid or medication, and try to remain patient and optimistic. A dead hostage is worth nothing to the kidnappers, and people will be working tirelessly for your release. It may, however, take some time.

Road safety

The standard of driving, vehicles and road conditions in Sudan are substantially lower than they are in Europe and the US. Consequently you are at risk of traffic accidents whether you drive yourself, hire a car and driver, or use public transport. Pedestrians and cyclists also need to be hyper-aware of other road users.

Across Sudan only major roads are tarred and street lighting is rare, as are working headlights on other vehicles. If there is a seatbelt available, wear it. Don’t use your mobile phone whilst driving (it is illegal even in Sudan) and expect a variety of vehicles (both motorised and four-legged) to approach you at speed from any angle. Keep your wits about you.

Checkpoints (both official and less-official) are a regular nuisance in Sudan, particularly close to airports and other sensitive areas. Approach them slowly and have copies of your documents easily to hand: on top of the dashboard is ideal. Deal with guards politely and be patient as they examine your paperwork, vehicle, etc. Sharing a cigarette or some sweets may speed up proceedings, as will taking tea or passing round a bottle of water (you don’t have to drink from it afterwards). If there is a problem, genuine or otherwise, try to negotiate rather than being confrontational. Make an effort to understand who is in charge and talk to him directly. If you have to make a payment, request a receipt and make the issuing officer sign it.

Car-jacking is a problem across Africa and, although currently uncommon in Sudan, it is still a possibility. Be aware of motorists around you, vary your route so it is not predictable, and if you feel uncomfortable do not stop, even at traffic lights. Do not pick up hitchhikers.

Female travellers

Traditional Sudanese families are very much divided on gender lines, and this influences everything from the tasks people do to who they meet with, where they sit in the home, and what they eat. Whilst foreign women are often considered as ‘honorary men’ and may be given the option to move between these male- and female-dominated spheres, foreign men are unlikely to be able to do so.

The vast majority of women travellers have favourable impressions of the country, and it is generally considered safe for single women. The threat of crime and physical harassment are relatively low, particularly compared with neighbouring countries, and Sudanese (both men and women) will often go out of their way to help a woman travelling on her own. That said, you should take the usual precautions: travel with a companion wherever possible, make sure that you are not out late at night, and dress in a manner that does not attract undue attention. If you feel uncomfortable in a situation, leave quickly and head for a well-populated place. Cafés, hotels and bus stations are ideal.

One area that does have potential pitfalls for women is the cheapest end of the accommodation market. Lokandas are based on communal sleeping arrangements, so the arrival of a female traveller (even one with a male companion) can sometimes provide managers with a headache as they wonder where they are going to put you. Most tend to have smaller separate rooms that you will be offered, though if none are available you may be turned away.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Homosexuality is illegal in Sudan and it is a capital offence for repeat offenders. Discussion of homosexuality is also taboo. Though it is not uncommon for people of the same gender to share a hotel room or to hold hands in public, gay and lesbian travellers should be exceptionally cautious when discussing their sexuality and should refrain from public displays of affection.

Travelling with children

Sudan is not an easy destination for travel with children. The heat, poor infrastructure and typically basic accommodation make it better suited for older, hardier individuals. That said, the Sudanese people are very family-orientated and sites such as the pyramids, temples and the National Museum are a fantastic way to bring history alive: children approach the royal cemeteries in particular with great enthusiasm. Find a guide who can share the most interesting (and, for the children, usually goriest) stories with you and it’ll certainly be a holiday to remember.

Bring with you all the products your children will need – items such as disposable nappies and recognised brands of baby formula are not widely available. Protect your child from the sun and make sure they keep drinking – children become dehydrated very quickly, especially if they have had an upset stomach. Hygiene is an ongoing concern, so several packets of baby wipes and alcohol hand gel will be particularly useful.

Travelling with a disability

Sudan is not really equipped for disabled travellers. It is rare to see severely disabled Sudanese in public, in part due to the shortcomings of the healthcare system, and buildings tend not to be wheelchair-accessible. Whilst you may find support at individual hotels, this cannot be counted upon when out and about or using public transport. If you are disabled and considering a trip to Sudan, it is advised you approach a tour operator, discuss your individual situation and establish what provisions, if any, can be made.

Travel and visas in Sudan

Visas

Sudan and red tape go together like mosquito bites and itching – take a deep breath and get used to it. From the moment you apply for your visa until you pass out through emigration to fly home, there will be interminable pieces of paperwork and stamps that appear to serve no genuine use and merely inconvenience everyone involved.

All visitors to Sudan require a visa. Nationals of most Arab countries can pick these up on arrival; all other nationalities need to apply in advance. Tourist visas are normally valid for a one-month stay, to be used within a month of issue. Sudanese bureaucracy is slow, so timing your visa application carefully is important. Visa fees can vary considerably – at the time of going to press the price of a one-month visa was £55 for a UK or EU passport holder and US$151 for a US passport holder.

Visa applications made outside of Africa require a letter of invitation from a company or individual in Sudan. This must be approved by the Ministry of Interior in Khartoum (though this is not necessary for some mainland European passport holders) and then sent with your forms to the embassy where you are applying for your visa. If you are travelling on an organised tour, your travel company will arrange this. A local Sudanese tour operator such as Lendi Travel can also arrange this invitation for a fee.

If you cannot get a letter of invitation you can still apply for a visa, but you are entering uncharted waters, as your application will be sent to Khartoum for approval. Embassy staff in London freely admit that applying this way can take up to 12 weeks, with no guarantee of acceptance! Persistence in this paper chase may help but is no guarantee of success, and given that visas are valid for a month from the date of issue, applying too early adds another element of risk to the process. If you apply this way, the embassy only asks for your passport and visa fee once Khartoum has approved your application.

The embassies in Cairo and Addis Ababa are particularly useful for travellers as they are allowed to issue visas without reference to Khartoum, speeding up the application process considerably. It is common to request a letter of introduction from your home embassy, which bumps up the price considerably for British passport holders. A visa in Cairo costs US$100 for 30 days, usually issued within 24 hours. Typical visa fees in Africa are around US$55.

If you are travelling as part of an organised tour or make a special request to Waleed at Lendi Travel, it is possible for you to collect your visa on arrival in Sudan. This is particularly common if you are visiting Sudan on a diving trip. You’ll need to provide a photocopy of your passport, after which they will send you a copy of your visa authorisation from the Ministry of Interior (which you will need to board the plane to Sudan). You pay a fee of around US$120 to the operator for the service, plus the visa fee at the counter before immigration. It is possible to arrange a visa on arrival in as little as three working days before you fly.

If your passport contains evidence that you’ve visited Israel – including entry or exit stamps from Egyptian or Jordanian border posts with Israel – your visa application will automatically be rejected. It is no longer possible to visit South Sudan on a Sudanese visa – since the secession of the South in 2011 you will require a visa for each country, and it is not yet possible to get a visa for South Sudan in Khartoum. Applications must instead be made in Addis Ababa, Kampala or Nairobi.

Getting there and away

By air

Sudan’s national carrier is Sudan Airways. They mainly operate inside Africa and between Africa and the Middle East, largely because their poor safety record does not permit them to fly within EU airspace. Potentially useful flights go to Addis Ababa (1hr 30mins), Cairo (2hrs 30mins), Dubai (4hrs) and Jeddah (1hr 30mins), from where it is possible to get onward connections anywhere in the world.

Travelling from Europe, Lufthansa and KLM offer direct flights to Khartoum. Turkish Airlines offers a large number of flights from across Europe, with a plane change in Istanbul.

Sudan has excellent connections with the Middle East. The Gulf Arab airlines of Emirates, Etihad Airways, Fly Dubai, Gulf Air and Qatar Airways all have regular services with good onward connections. These options are particularly useful for travellers flying to or from the US and Australia. Royal Jordanian, Saudi Arabian Airlines, Syrian Air and Yemenia also run flights to their respective capitals.

Within Africa there are three major airlines serving Khartoum. Ethiopian Airlines has the best connections throughout the continent and the Addis Ababa–Khartoum service often continues on to Cairo. Egypt Air has flights to Cairo that connect with its European routes, and Kenya Airways has a direct flight to Nairobi (3hrs). There is no longer a separate departure tax payable when leaving Khartoum by air – this is now included in the price of your airline ticket.

By land

A quick glance at the map suggests that Sudan, with its numerous neighbours, should present a wide choice of entry points for those arriving overland. A closer look cuts down the options. Only the borders with Ethiopia and Egypt can be said to offer truly reliable access – good news for those on the classic ‘Cairo to Cape Town’ overland route. Access across other borders either depends on the political climate, or has simply not been possible for years.

Entering Sudan from Ethiopia is a straightforward affair, with transport links much improved in recent years. It is cheap and easy to use public transport to make the crossing, and, providing your paperwork is in order, there should be no difficulty bringing your own vehicle. To the north, although the border with Eritrea is currently open, foreigners are advised against all travel within the border zone due to instability caused by extreme poverty and smuggling. The land border between Sudan and Egypt is closed due to a long-running dispute over ownership of the Haleib Triangle, but the ferry along Lake Nasser is a reliable transport alternative for both passengers and vehicles.

Approaching Sudan from the west, the most common entry point into Sudan is from Chad at El Geneina. Closed in 2003 due to the conflict in Darfur, the border opened again in April 2010 as the two countries attempted to normalise relations. Both Amnesty International and the UN have expressed concern about ongoing violence in the border region, however, and it is not generally considered safe for foreigners due to the threat of kidnap and shootings. The border with Libya has been closed since 2010 but may reopen at any time.

Although ten official border crossings were opened between Sudan and South Sudan following the latter’s secession in 2011, the resurgence of violence in 2012 has made it inadvisable for foreigners to travel within 65km of the border. The situation is changing constantly, and so visitors contemplating crossing to or from South Sudan are advised to check the latest advice from the FCO.

By boat

The weekly ferry along Lake Nasser (or the Nubian Lake as the Sudanese prefer to call it) is a leisurely way to enter Sudan from Egypt. The ferry usually tows a barge should you need to ship a vehicle. An alternative is to cross the Red Sea from Saudi Arabia, which takes approximately 13 hours. Vehicle and passenger ferries run regularly between Jeddah and Suakin. The service occasionally continues up the Red Sea from Port Sudan to Port Suez, but this is too unreliable for advanced planning.

Getting around

By air

Sudan Airways has domestic flights covering the whole country. The timetable is moveable at best, and flights are liable to be changed or cancelled at short notice. Busy flights (such as Khartoum–Port Sudan) tend to run better than others, and the most common reason for cancellation is that not enough people have bought tickets. Reconfirming your ticket the day before the flight is highly recommended. Regular flights are available to El Fasher, El Obeid, Geneina, Kassala, Nyala and Port Sudan. The most useful of these is the daily flight to Port Sudan. It is also possible to charter a plane.

Sudan Airways leases its planes from foreign countries. An accident at Khartoum airport in 2008 resulted in all of the airline’s planes temporarily being grounded. The accident rate of Sudanese airlines in general is poor (21 major accidents between 2003 and 2008) and, consequently, all airlines registered in Sudan are banned from operating in the EU. Weigh up the pros and cons of flying, sit next to the emergency exit if you have the choice, and if you are walking across the runway to the plane, do not walk in front of the propellers. Even at a distance of 20m it is possible for things to get sucked into the blades.

By road

Wherever you want to go in Sudan, getting there will be half the fun. Riding around on the roof of a truck is still a distinct possibility, but things are getting easier: the amount of sealed roads in Sudan has greatly increased, particularly in the north and it is now possible to travel almost the entire distance from Khartoum to Wadi Halfa on tarmac, as well as between Atbara and Port Sudan.

Sudan is a huge country, and you should allow plenty of time to get around. No-one is in a rush, so it’s best to adopt a Sudanese outlook on the trip (and indeed your whole stay in Sudan). Even luxury coaches can get flat tyres, and the best drivers can get stuck in sand. The journey may take a while but you will get there eventually, inshallah. Bad roads and cramped buses can be physically very wearing, so make sure you allow as much time as you can between long trips for recharging your batteries.

One thing to bear in mind when travelling by road is dust. Few roads are paved in Sudan, so dust is a perennial problem. Keep a scarf or bandana handy to protect your nose and mouth. Failure to do so will more often than not result in a nasty cough, and long hours travelling on dusty tracks are a major culprit.

By bus

Sudan has a large variety of transport options falling under the loose category of ‘bus’. At the top end of the scale, luxury coaches link Khartoum to Port Sudan, Kassala, Atbara, Dongola, Karima, El Obeid and Dilling. They are fast and comfortable, run to a set timetable, and you generally get plied with hot and cold drinks and snacks between meal breaks. This is the most expensive bus option, but the reclining seats are positively heavenly if you’ve been bumping around in a pick-up for much of your trip. Companies running these coaches include Jamel El Dien, MCV, Igbalco and Marshal.

Mid-range buses ply the same routes, but are much slower and have a more relaxed attitude to squeezing in passengers. You can certainly forget about having your own dedicated seat. These bus companies are usually only signed in Arabic and many appear to have a coach body attached to a truck chassis. In Sudan’s west and far north where tarmac is rarer, the Sudanese have truly made the bus their own. These vehicles really are just trucks masquerading as buses, with seats welded in the back, and open sides to let in the elements. Built to last, with little consideration for speed or comfort, they are the cheapest – and often the only – option available. Passengers and their worldly goods are crammed inside, while enough baggage is lashed on top to double the vehicle’s height.

Minibuses (hafla) link towns relatively close together and are fast and convenient. There’s no need to pre-book – just turn up at the bus station; the minibus departs when full. At the bus station you’ll find bus company offices where you can pre-book tickets. Long-distance transport usually departs early in the morning (typically around 06.00), so it’s wise to check departure times in advance. While you wait there are stands to get a bowl of ful or a kebab, and the ubiquitous tea ladies with their stalls.

Boksi

The workhorse of rural Sudan is the pick-up truck, known locally as a boksi (plural bokasi). Almost always a Toyota Hilux, these are the most common form of transport where there is no sealed road, particularly in north Sudan. Quicker than a bus over the same ground, they are also slightly more expensive. Bokasi are a fast and furious way to travel. The cab has two seats next to the driver and the covered back of the pick-up has bench seating along each side, with five passengers crammed on each row. Any free floor space is taken up with baggage, with an unlimited number of children thrown in for good measure. Latecomers sit on the roof. The benches are hard and you can feel every bump. If you can, avoid the space over the tailgate – whenever the vehicle hits a pot-hole you’ll be liable to go flying. Short trips are fine, but a long journey can leave you cramped and bruised if the road is particularly bad.

Most boksi companies have offices where it’s possible to book a seat a day in advance – look for a painted picture of the vehicle, with the destinations listed in Arabic. Your name is written on a passenger manifest, with payment usually collected just before departure. The more comfortable seats next to the driver cost a quarter to a third more than those in the back and are always the first to be reserved.

Self-drive

For many years travellers have visited Sudan as part of a larger trip through Africa. In fact, on recent trips to Sudan I got the impression that independent travellers with vehicles actually outnumbered the backpackers. Having your own vehicle gives you the ultimate freedom to travel where you want, and camping under the stars can really let you enjoy Sudan at its most spectacular and wild.

There are several excellent resources out there to help you with your preparations for overlanding. Bradt’s Africa Overland by Siân Pritchard-Jones and Bob Gibbons has comprehensive information on vehicle preparation, route planning and dealing with bureaucracy, and a handy gazetteer for the entire continent. Three other guides also stand out – the encyclopaedic Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide by Tom Sheppard, The Adventure Motorcycling Handbook by Chris Scott and the 2011 edition of the Overlanders Handbook, also by Chris Scott.

Four-wheel-drive is essential for overlanding in Sudan. In the west and far north you can frequently find yourself driving on sand and will need the extra power to keep yourself from getting stuck. The Land Rover is still the vehicle of choice for most overlanders, and there are enough in Sudan to make spares readily available. There are several Land Rover dealers in Khartoum who can source unusual spare parts; at the other end of the spectrum local mechanics are often geniuses of improvisation when it comes to repairs. Sudan’s most popular 4×4 is the Toyota Land Cruiser, a vehicle all garages will be familiar with. Spare parts can be hard to find for motorbikes.

Whatever your vehicle, there are several important points to consider. Fuel and water are top of the list. Carry as much fuel as you can to increase your range. Away from the large towns, fuel can sometimes be hard to come by, so always make sure your spare container is kept topped up. This is more problematic for motorcycles as sandy conditions reduce your range.

Anything less than a 35l-capacity tank may result in problems in the northern deserts or the west. Petrol (benzene) in Sudan is sold by the gallon. Diesel is three-quarters of the price but harder to find in smaller places. Along with fuel, carry as much water as possible, both for yourself and to cool your engine in case of overheating.

Other essentials to carry are a comprehensive tool kit and manual for your vehicle, key spare parts and tyres, and a first-aid kit. If you plan on doing any driving in the desert, sand mats are strongly recommended. Many overlanders also use GPS units these days. Road surfaces vary greatly and local conditions can be unpredictable, with a gravel surface suddenly giving way to a kilometre of windblown sand before changing to deeply rutted tracks.

Sand presents the greatest problems for driving, most notably if you choose to follow the railway tracks from Wadi Halfa to Berber. Never speed across open desert as the surface can suddenly give way to gullies or soft sand, bogging your vehicle down. If you need to, reduce the tyre pressure to increase the vehicle’s footprint (motorcycles may profit from using wider tyres in Sudan).

As always, other travellers are the best source of up-to-date information on road conditions – the Blue Nile Sailing Club in Khartoum has been the de facto meeting place for Sudanese overlanders for several years.

Car hire

There are plenty of car-hire places in Khartoum, mostly with showrooms strung out along Africa Road near the airport. Car hire is expensive in Sudan, with prices typically quoted at around US$100 a day for a two-wheel-drive, and 50% more for 4×4. If you plan on driving off-road – quite likely given the nature of the country – the vehicle will be supplied with a driver, pushing costs up even more. If you do want to head out into the desert, it’s far better to organise things through a local tour company, who should also be able to provide you with maps and GPS navigation along with the driver.

By train

At independence, Sudan had the most extensive and best-run railway in Africa. Years of under-investment and (often wilful) neglect mean that the Sudan Railways Corporation now runs a strictly limited service, with the only useful route being the weekly train between Khartoum and Atbara. The extension from Atbara to Wadi Halfa was suspended with the opening of the new road in 2010. There’s a service running west from Khartoum to Nyala every couple of weeks, but it is pretty much freight only.

Rail is a relaxing way to travel, but certainly not a fast one. Trains aren’t always maintained well, sandstorms can stop progress, and tracks often need clearing. Mysterious stops in the middle of nowhere for several hours do occur. As with so much in Sudan, the trick is not to be in a hurry and to enjoy the journey for what it is. The Sudanese seem to possess an almost saintly patience when faced with the limitations of the transport network, an approach worth emulating. Just remember, you will get there in the end!

Trains have three classes. First and second class have separate compartments off a corridor. There’s no difference in the quality of the seats, merely in the amount of room: first class takes six passengers per compartment; second class squeezes eight into the same space. Third class is open seating, with just a thin layer of foam providing any padding on the wooden benches. After a few hours this can be excruciating, so a sleeping bag or similar can come in handy for a little extra cushioning. All human life is here in third class, packed in like sardines with precious little room to manoeuvre.

On an overnight trip, space is at a real premium. Passengers seem to appear out of nowhere as everyone tries to bed down for some sleep. Not an inch of space is wasted. The corridors turn into dormitories, so navigating your way from one end of the carriage to the other becomes a real obstacle course as you try not to step on any slumbering figures.

You often see people riding on the roof of the carriages, claiming their ride for free. It’s a precarious position to take. You need some genuine acrobatic ability to get up on the roof, and even if the train is only trundling along at 40km/h that can seem plenty fast enough when you don’t have any hand holds. There’s also no protection from the elements – most likely a beating sun in the day and a desert chill at night.

The Nile has long been Sudan’s major transport artery, although travellers are unlikely to make great use of it. Compared with Egypt, the Nile in Sudan can often seem an empty river. The only long-distance passenger ferry in the north of the country is the weekly service across Lake Nasser between Wadi Halfa and Aswan. Until ten years ago there was a regular service between Dongola and Karima when the Nile waters were high enough. The remains of this fleet can be seen rotting on the riverbanks just outside Karima.

Anyone travelling in the north can make use of either the local ferries to cross the Nile, or the newly built Chinese bridges. These ferries range in size from large flat-bottomed barges capable of carrying a bus or two, down to small dinghies with outboards for foot passengers. Fares are typically around SDG1 for foot passengers and SDG7 if you have a vehicle, depending on the size. Some crossings have a ticket booth; otherwise you pay the fare when you get on. Ferry crossings are part of the fabric of the north and all human (and animal) life seems to congregate at them – boys driving goats, women carrying shopping, mules being shooed out of the way of a slowly reversing pick-up. The busiest landing stages have a cluster of tea houses and food joints, and are great places to spend a few hours people-watching.

South of Khartoum, the Nile is navigable as far as Juba in South Sudan. Barges and the occasional steamer depart from the White Nile port of Kosti, stopping at Malakal (also in South Sudan). It takes around ten days to sail upstream to Juba and around four days in the reverse direction. Slowly making your way through the swamps of the Sudd could be one of Africa’s great boat trips, but for the moment this trip is only for the hardiest of travellers. Boats are designed for cargo rather than passengers, and extreme delays – literally weeks of waiting for barges on the White Nile are not uncommon.

When to visit Sudan

Climate

Until the secession of South Sudan in 2011, Sudan was the largest country in Africa, covering 8% of the continent’s surface. Even now, if you have the opportunity to travel across the country, you should do so: the scale and diversity of the land is striking. The Sudanese often describe their country as the whole of Africa in one country. It’s easy to understand why: Sudan ranges from desert in the north to mountains in the south, the whole bisected by one of the greatest rivers in the world. Straddling the fault-line between the Islamic world and sub-Saharan Africa – the Arabs call the country bilad as-sudan, or ‘land of the blacks’ – it is superlative in every sense.

Sudan is divided into four main geographical regions, roughly corresponding to the cardinal points. The country is tropical with both a rainy and a dry season, although the temperature and amount of rainfall depend greatly on location. North Sudan is desert and receives little or no rainfall. To the west is the Libyan Desert, part of the Sahara proper, and to the east is the barren Nubian Desert. It is whipped by dry northeasterly winds from the Arabian Peninsula and habob, summer afternoon dust storms that cut visibility to zero. It wasn’t always like this, however. Access to water was key to the rise of the Nubian kingdoms. Nile tributaries running through this region made the land lush, enabling them to raise cattle and accrue immense wealth – so much so, in fact, that they became an attractive target for Egyptian invaders from the north. Their civilisation fell victim to climate change around 300BC when arable land ceased to be viable. The desert has encroached ever since.

West Sudan is semi-desert, with rolling sand dunes and light grasslands that rise to the highlands of Darfur. There are no permanent rivers, only wadis (seasonal watercourses) that spring into life with the summer rains and leave rich alluvial soils behind. The Marrah Mountains in central Darfur are a range of volcanic peaks last active some 4,000 years ago. Their high-point, the Deriba Caldera, rises 3,042m above sea level, and the area enjoys a temperate climate with high rainfall and numerous springs. US geologists at the Center for Remote Sensing in Boston have identified an underwater lake three times the size of Lebanon that may in the future provide water to sufficiently irrigate the land and, as a result, resolve many of the conflicts linked to competition for resources.

East Sudan is dry grassland: the Gash Delta near Kassala acts as a seasonal drain for the region and produces rich grazing for the livestock of pastoral nomads. The barren spine of the Red Sea Hills separates the coastal plain from the rest of Sudan; the rising Ethiopian Plateau naturally demarcates the eastern border. Though all of Sudan becomes hot in the summer months, temperatures in Port Sudan climb higher still: summer highs of more than 50°C are not uncommon.

In the south are the Nuba Mountains, a remote region of South Kordofan that straddles the contested border between Sudan and South Sudan. The climate is semi-arid with a rainy season stretching from May to October. Rainfall is heaviest between June and September (as much as 15cm per month) and average temperatures, though slightly higher in the months before the rain, tend to vary very little.

What to see and do in Sudan

Confluence of the White and Blue Niles

Known locally as Al Mogran, the confluence of the Nile is one of Africa’s geographical highlights. From here you can look east along the fast and narrow Blue Nile stretching to Ethiopia; turning south you are faced with the White Nile, wide and lazy, exhausted by its passage from Lake Victoria through the swamps of the Sudd. The two Niles are distinct colours (or at least shades of muddy grey) on account of the silts they carry, and you can see the streams flow next to each other before mixing to complete the mighty river.

During the summer months when the Blue Nile is at its highest level, the flow of water is so strong that it causes the White Nile to back up, flooding parts of southern Khartoum in bad years. The difference in colour between the two rivers is particularly noticeable at this time.

In 1772 the Scottish explorer James Bruce passed through, claiming to have found the source of the Nile in Ethiopia. He had traced the Blue Nile from its source at Lake Tana, and was disheartened to reach the confluence to find an equally mighty river joining the waterway. It would take nearly 100 years more for the source of the White Nile to be located by John Hanning Speke.

In many countries, a site like the Nile Confluence would be heralded with signposts and viewpoints. The Sudanese are happy to let things like this pass, as unhurried to draw attention to it as the lazy waters of the river itself. In fact, the less attention drawn to it the better as far as the security forces are concerned. Anyone pulling out a camera on the White Nile Bridge overlooking the confluence is likely to be approached by a security guard (probably dressed as a civilian). The bridge is regarded as ‘strategic’, so photography (even with a permit) is expressly forbidden. Strangely, the postcard sellers outside the main post office will happily sell you a snap of the bridge, although this irony seems to have gone unnoticed by the authorities.

For photography, try the Mogran Family Park next to the bridge (open: 10.00–23.00, rides from 15.00; admission SDG3). For the best view of the confluence, take a ride on the Ferris wheel. You should be able to snap away happily from up there. Alternatively, hop on a ferry to Tuti Island and walk to its northern tip, where the blending of the Nile waters is at its strongest.

Jebel Barkal

The holy mountain of Jebel Barkal (Jebel Barkal actually means ‘holy mountain’ in Arabic), a great sandstone butte that dominates this stretch of the Nile, is situated 2km southwest of the centre of Karima (a 15-minute walk or SDG5 in a rickshaw). The ancient Egyptians and Kushites alike believed that the mountain was the home of the god Amun, the ‘Throne of Two Lands’ – Egypt and Nubia. The ruins of a temple dedicated to the god lie at the foot of the mountain. At dawn or dusk, Jebel Barkal still evokes a phenomenal aura and it’s easy to understand why the ancients ascribed such religious significance to it.

Thutmose III, one of the first Egyptian kings to penetrate this far south, built the first Temple of Amun in the 15th century BC. Later pharaohs, including Rameses II, expanded it, turning it into an important cultural centre, as well as a way station for goods from the south destined for the great Temple of Amun at Karnak. When Egyptian influence waned the temple fell into disrepair.

The rise of the Kushites changed the fortunes of the whole region. Jebel Barkal became the centre of the new kingdom and its kings resurrected the worship of Amun. In around 720BC Piye led his armies north into Egypt and captured Thebes. Ownership of the Temple of Amun gave legitimacy to his claim to be the true representative of Egyptian traditions; his successors set up the 25th Dynasty and ruled from Thebes and Memphis as pharaohs. Piye greatly expanded the temple at Jebel Barkal, as did his son, Taharqa. Over time the temple grew to over 150m in length, making it the largest Kushite building ever built.

The temple stretches out towards the Nile, near the bottom of a freestanding pinnacle of rock cracked from the sandstone cliffs. The significance of this pinnacle has puzzled archaeologists for decades. An early observer supposed that it was to have been a giant statue of a pharaoh, far surpassing anything in Egypt at 90m high. A more likely explanation is found in its profile, which (albeit roughly) resembles an ureaus – the protective cobra and symbol of the king. A relief in Rameses II’s massive temple at Abu Simbel in Egypt shows Amun sitting inside a mountain, faced with a rearing cobra. This iconography is found in later Kushite art and almost certainly represents Jebel Barkal. In the 1990s, archaeologists discovered a niche at the summit of the pinnacle carved with hieroglyphics proclaiming Taharqa’s military campaigns against his enemies. This was completely inaccessible (except to the gods) so would have been covered with a gold panel, allowing it to reflect in the light and provide a beacon for miles around. The light of Jebel Barkal would have been clearly visible from Taharqa’s pyramid upstream at Nuri.

The temple is very ruined and much of the structure is covered with sand, but the ground plan is still clear, with a procession of two large colonnaded halls leading into the sanctuary at the base of the mountain, surrounded by several small rooms. At the southern entrance of the temple there are several wind-worn granite statues of rams; these were actually from Soleb further downstream and have been relocated here. There are many scattered blocks covered with reliefs and hieroglyphics.

Khartoum

Sitting at the place where the waters of the Blue and White Niles meet before continuing their slow progress to Egypt, Khartoum has a fantastic setting. It’s a melting pot of the many ethnic groups that make up Sudan, and to sit at a tea stall watching the world pass by is to watch a progression of tribes and nationalities, from Arab, Dinka and Shilluk to Nubian, Beja and Fur.

Khartoum is actually three cities in one. The oldest part – Khartoum proper – sits between the confluence of the Blue and White Niles. On the west bank is Omdurman, the old Mahdist capital, and on the north bank the semi-industrial city of Khartoum North (also sometimes called Bahari).

Khartoum used to bear the unflattering moniker ‘the world’s largest waiting room’. The capital of a dry country, it was a quiet, relaxed city where nothing much seemed to happen, and no-one was in a hurry to do it. While that’s still true to some extent, Khartoum has changed massively in recent years, due mainly to oil wealth. The city is now plugged into the global markets, with huge investments being made from China and the Gulf States. Top-end hotels have sprung up, suburban housing developments have sprawled, and new bridges have been thrown across the river. The Sunt Forest, an area of scented acacias near the Nile Confluence, has been ripped up to make way for a colossal business park. At the same time, the expat population has swollen considerably, due to international development organisations relocating into the city and the constant influx of Chinese oil workers. The much-anticipated population exodus following the secession of South Sudan has not materialised, largely due to ongoing fears about security and the financial costs of relocation.

Khartoum has been witness to the many coups that have shaped Sudan’s post-independence history. Its large European (mainly Greek) population has mostly disappeared, the last exodus prompted by Nimeiri’s establishment of sharia law in 1983 and the coup that brought the Islamists to power in 1989. In response to the bombing of the US embassies in east Africa, US president Bill Clinton ordered a cruise missile attack on a pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum North in August 1998, although there has subsequently been no evidence that it was involved in manufacturing chemical weapons as alleged. The population of Khartoum increased massively as a result of the civil war. Displaced people’s camps filled with Southerners, and later Darfuris, sprung up around the edges of the city, although many Southerners have now returned home after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and secession of South Sudan in 2011. Inward investment from China and the Gulf has changed the skyline in the last few years, creating a greater feeling of optimism amongst many of the city’s residents.

Khartoum is still as friendly and safe as it ever was, and remains one of Africa’s most laid-back capital cities, but these days there’s the faintest hint of an African Dubai in the wind, albeit with added chaos and camels.

Khatmiyah Mosque in Kassala

This delightful old mosque sits at the base of the Taka Mountains and is the most important centre for the Khatmiyah Sufi tariqa in Sudan. Mohammed Osman al Khatm founded the order at the end of the 18th century, bringing it to Sudan from Arabia. The mosque is dedicated to his son, Hassan al Mirghani, who did much to spread the Khatmiyah’s teachings until his death in 1869. It is believed to have been built on soil brought by al Khatm from Mecca, making it even more holy. Hassan al Mirghani’s tomb stood on the site of the original mosque, which was destroyed by the Mahdist Ansar in the 1880s. Visitors come to pray to receive baraka (blessings) from the tomb of Hassan, who has been elevated to the position of a wali – the closest that Islam comes to a saint.

The mosque is of plain brick, with a pointed octagonal minaret. The main prayer hall is open to the elements, with its arcades of columns. Attached is the domed ghobba (tomb) of Hassan. The drum of the dome is similarly open and local tradition has it that when it rains the tomb remains dry. There is a very peaceful air around the mosque. Women sit at the threshold selling dates and seeds, boys read the Koran in the attached school and there is a regular stream of people arriving to pray, against the low Sufi chant of La illaha illallah (‘there is no God but Allah’). During Eid al Adha, the mosque is packed with people bringing sheep for the ritual sacrifice. Non-Muslim visitors are welcome, but it is polite to ask before entering or taking photos. A more relaxed example of the traditions of Sudanese Islam is hard to imagine.

Behind the mosque, the huge boulders of the mountains are a fine place to watch the proceedings, with their views of Khatmiyah and Kassala. It takes nearly an hour to walk to Khatmiyah from the centre of Kassala following the main road southeast; alternatively you can take the bus (SDG1) or a taxi (SDG15). The minaret is clearly visible from the road – any minibus to the village will also be able to drop you off. The mosque is a 15–20-minute walk from Toteil village.

© Sophie Ibbotson and Max Lovett-Hoare

National Museum in Khartoum

The National Museum holds many treasures of Sudan’s ancient and medieval past. They’re well presented and labelled, and give a good narrative of Sudanese history. Spread out over two floors, the ground floor starts with Sudan’s prehistory and covers the rise of Kerma and Kush in great detail. Kerma is particularly well represented through its famous pottery. The Kushite displays show the wide variety of cultural exchange in play throughout the kingdom. Egyptian culture is the strongest influence, shown particularly in the royal statues found at Jebel Barkal dating from around 690BC and the sarcophagus of Anlamani from his tomb at Nuri about 100 years earlier. A clear Hellenistic influence can be seen in the statue of the so-called ‘Venus of Meroë’ and a blue-glass chalice from Sedeinga, with depictions of gods and bearing a Greek inscription ‘You shall live’. A side room on the ground floor has space for temporary displays, often illustrating current archaeological digs.

The upstairs gallery holds the museum’s most unexpected displays – frescoes from Christian Nubia. Despite lasting for 700 years, Sudan’s early Christian kingdoms are little known to the outside world and repeated Sudanese governments have shown little interest in promoting this aspect of their history. I was as ignorant as most on my first visit, and was astounded to find beautiful frescoes depicting Christ and the Virgin Mary, along with a host of archangels, saints and apostles. The style of the frescoes is distinctly Byzantine, reflecting Nubia’s links with the Roman Empire in the east. Most were painted between the 8th and 14th centuries, and were taken from the cathedral at Faras, now submerged under Lake Nasser. The upstairs galleries can be a little dark, so you may want to take a torch with you in order to see the details in the frescoes.

Underneath purpose-built structures in the museum’s grounds are three remarkable temples rescued from the flood waters of Lake Nasser in the 1960s and resurrected here. The Temple of Kumma dates from 1473–1400BC during the reigns of Queen Hatshepsut and the pharaohs Tuthmosis III and Amenophis II. It was part of a series of fortresses built during the Middle Kingdom period to control the movement of goods and troops up and down the Nile. This particular temple was located at the Semna Cataract approximately 60km south of Wadi Halfa, which was then the frontier of Egyptian control. Part of the much larger Kumma Fortress, whose outer walls reached 10m high and 5m thick, the temple was situated in the northwest corner of the settlement and originally surrounded by mud-brick houses and storerooms connected with the everyday life of the priests and the worshippers.

Roughly contemporary with the Temple of Kumma is the Buhen Temple, dedicated to the falcon god Horus. What you see here is an inner temple divided into five rectangular rooms that would, in ancient times, have been surrounded by an outer courtyard with mud-brick walls. When Tuthmosis III came to power around 1450BC he systematically removed the names and depictions of earlier rulers and substituted them with his own. He also enlarged the complex significantly and placed within it stele proclaiming his victories in Libya and Syria. Later rulers altered the entrance way and widened the doors. The temple remained in use as late as AD450, after which time it was partially incorporated into a church.

The third temple is the Temple of Semna, built by the pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom as part of the fortifications at the Second Cataract, 60km south of Wadi Halfa. The temple was dedicated to the Nubian god Dedwen and the main building was constructed from stone, surrounded by a mud-brick wall. Projecting columns known as pilasters decorated the central courtyard and the reliefs, a later addition to the structure, depict Tuthmosis III. The temple remained in use at least until the 7th century BC. If you are interested in Sudan’s archaeology, the museum hosts regular archaeological conferences and seminars that are open to the public. Ask at reception for details.

© Andreas31, Wikipedia

Nuba Mountains

Heading south from El Obeid, the flat plains of Kordofan are suddenly and startlingly interrupted by the broken hilltops of the Nuba Mountains. It’s some of the most fertile and picturesque land in the whole of the country, inhabited by the Nuba, a conglomeration of proud, culturally diverse Black African farmers. The Nuba Mountains cover around 50,000km2, and have an estimated population of 1.5 million people – mostly Nuba but with a significant minority population of Baggara (cattle-raising Arabs). At the geographical centre of Sudan, the Nuba sit neither fully in Sudan nor South Sudan, which has made their land a major battleground in the civil war, and as such it has been largely inaccessible for the best part of two decades.

In 2002, the Sudanese government and the SPLM/A signed a ceasefire agreement in the Nuba Mountains; it was one of the breakthroughs that eventually led to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement reached in January 2005. The Nuba Mountains continues to have a large military presence, numerous refugees, and an unpredictable security situation. It is not recommended to travel within 50km of the border at this time. The Nuba Mountains is an area of continued tension, so if you do plan to visit, a travel permit is required. Permits cover the main towns – Dilling and Kadugli – rather than the region in its entirety, and you should request any exceptions when applying in Khartoum. Nevertheless, it should be fine to explore the areas and villages close to the towns, without further permissions. That said, registration with the police is also a must, and should be the first thing you do on arrival in each town.

The Nuba Mountains are green and lush in many places, a mix of hills and rocky crags rising out of the plain. The landscape seems ideal for trekking and scrambling, but there is a landmine risk in many parts of the region. The UN Mine Action Service has made road clearing a priority and is being assisted by government forces. The banks of irrigation channels, unused paths, and the areas around abandoned garrisons are regarded as unsafe areas. Stick to well-worn paths where the locals walk and always remember that mines are laid to be invisible.

Nuba villages, with their neatly tended fields and thatched mud huts (jutiya), are very picturesque, but they are also poor. Sudanese hospitality means that you may be offered tea or food, so make sure you do not take advantage of your hosts. Small gifts of coffee or sugar are appropriate as practical tokens of your gratitude. Visitors to an area that has been isolated for so long have a special responsibility to ensure that they treat their hosts with particular respect and leave good impressions behind them.

© urosr, Shutterstock

Royal Pyramids at Meroë

Clearly visible from the Khartoum–Atbara highway, the pyramids of the Royal Cemetery of Meroë stand alone on a sandy ridge like a row of broken teeth. They are Sudan’s most popular tourist attraction, although in a country where tourism is in its infancy, popular is a relative term – you are still likely to have the site to yourself. The headline-grabbing treasures of Egypt have long overshadowed Sudan’s ancient history, but at Meroë the charm of the unknown is the great attraction – visitors can enjoy the rare sensation that they are discovering a long-hidden secret, without a tout offering a camel ride or belly dance in sight. Instead, it’s just you and the pyramids alone in the desert.

The site is divided into two main clusters – the Northern and Southern cemeteries. In total there are around 100 pyramids, although many of those are poorly preserved or exist only in outline traces. The South Cemetery is the older cluster, dating to around the 8th century BC, and the first kings who made the move from Nuri to Meroë were entombed here. Kings and queens continued to be buried at Meroë until the fall of Kushite rule in the 4th century AD.

While clearly Egyptian in inspiration, the pyramids are quite unlike those at Giza. The most notable difference is in size and pitch. The largest pyramid at Meroë is just under 30m high (or would have been were it still intact) with an angle approaching 70°. The smaller size allowed the pyramids to be constructed much faster and with less manpower, using simple cranes. Tomb chambers were dug directly into the rock below and the pyramid then erected above – a marked difference to Egypt, where the tomb is enclosed in the body of the pyramid. The pyramids have a rubble core encased in local sandstone (or brick towards the end of the Kushite period). The pyramids were then covered with a render of lime mortar to give a smooth gleaming surface, and the bases were simply painted in red, yellow and blue stars. On the eastern face each pyramid has a funerary chapel where offerings could be made to the dead.

The Northern Cemetery is the better preserved, and contains over 30 pyramids in various states of repair. Most have been decapitated. Their sorry state is largely the work of an Italian treasure hunter, Guiseppe Ferlini, who passed through in 1834. Ferlini was convinced that the pyramids contained great riches, and with the tacit support of the Turco-Egyptians, proceeded to pull them down. He struck gold on his first attempt. In Pyramid 6, that of Queen Amanishakheto, Ferlini found a hoard of jewellery in a chamber near the tomb’s apex. This was highly unusual, as grave goods were normally placed with the body in the tomb chamber beneath the pyramid. Thus inspired, Ferlini laboured on with his destruction only to come up blank – his greatest haul after this was nothing grander than some workmen’s tools. The gold, showing distinct Hellenistic influences, eventually found its way to the Egyptian museums in Berlin and Munich, while Sudan was left with a field of smashed pyramids.

Earlier damage was done by the tomb robbers of antiquity. As a result, comparatively little is known about royal funerary practices. Bodies were probably entombed facing east to greet the rising sun. The funerary chapels contain a mix of passages from the Egyptian Book of the Dead and offering scenes, often with Isis in attendance. At the centre of the Northern Cemetery is a small modern pyramid, its bright colour in stark contrast to the chocolate brown of its neighbours. This was restored in the 1980s as an exercise to recreate Kushite building techniques; its smooth rendered exterior gives some idea of how the pyramids would originally have appeared.

The older Southern Cemetery sits 500m south of the Northern cluster. There are over 60 smaller pyramids here, all belonging to the elite of Meroë. Many are totally ruined or lost altogether. A third, western, cemetery also contains noble tombs, including several well-preserved or reconstructed pyramids. Despite the otherwise apparent absence of people, it is sometimes possible to buy souvenirs from craftsmen outside the pyramids.

An old ruined harbour at Suakin © Sophie Ibbotson and Max Lovell-Hoare

Suakin Island

Legend has it that Suakin was once the home of magical spirits: King Solomon imprisoned a djinn (genie) on the island. A ship full of Ethiopian maidens was on its way to visit the Queen of Sheba when a storm blew it off course to Suakin. When it finally set sail again, the virginal girls were astonished to discover themselves pregnant, carrying the seed of the supernatural host.

Most of Suakin’s visitors were the victims of other, worldlier transgressions. Slaves raided from the southern fringes of the Sudanese state – Bahr al Ghazal and along the White Nile – were brought here to be shipped to the markets of Jeddah and Cairo. The Funj, Ottomans and Egyptians all prospered from the trade. The first European to record his impressions of Suakin was the explorer John Lewis Burckhardt, who in 1814 found it a place of ‘ill-faith, avarice, drunkenness and debauchery’. Around 3,000 slaves annually passed through Suakin, including Burckhardt’s own slave whom he sold at the market.

Suakin owed its success to its lagoon location, which was ideal for the shallow draught of Arab ships. A 3km channel was eventually cut through the surrounding reef to improve access. The coral that was dredged up was cut into blocks and used in the construction of the island’s buildings. These were then bolstered with wooden pillars and covered with plaster. A causeway was built in 1880 under the orders of General Gordon to link the island to the mainland. The town’s gate, 1km inland in a straight line from the causeway (and conveniently next to the minibus stand), also dates from this period.

Since the abandonment of the port 100 years ago, Suakin has been decaying rapidly. The island itself is deserted, and you can have the place pretty much to yourself. Most of the buildings are in terrible shape. One of the best-preserved buildings is Khorshid Effendi’s House, on the northeastern side of the island, which was occupied by Kitchener in the run-up to his campaign against the Khalifa. The fine wooden mashrabiya screens that covered the windows and allowed the female occupants to look out without being observed are long gone, but there is still evidence of the building’s fine decorative stucco. Two other well-preserved buildings are the Hanafi and Shafai mosques, with their distinctive stubby minarets. They were restored during the Turkiyah, but probably date from at least the 16th century. Along the western side of the island is the skeleton of a huge warehouse, a clearing house for both goods and people. Opposite the northern tip is the modern ferry terminal, still re-enacting the pilgrim route to Arabia.

This is one historical site in Sudan that doesn’t require a permit to enter, although the authorities manage to make up for this by charging a steep SDG10 to visit the island. There is a small office at the end of the causeway where you will be asked to buy a ticket.

Whirling dervishes at Hamed al-Nil Tomb in Omdurman

Sheikh Hamed al-Nil was a 19th-century Sufi leader of the Qadiriyah order (tariqa), and his tomb is the weekly focus for Omdurman’s most exciting sight – the dancing and chanting dervishes. Each Friday afternoon at around 16.00, adherents of the tariqa gather to dance and pray, attracting large crowds of observers and participants. A trip to see the dervishes should be a highlight of any visit to Khartoum.

The ceremony starts with a march across the cemetery to the tomb of the sheikh. It’s an amazing sight as the dervishes carry the green banner of the tariqa, their appearance a world away from the restrained white robes of most Sudanese. Instead, the jallabiyas are a crazy patchwork of green and red, often topped off with leopard skin, chunky beads and dreadlocks. As they march, they chant, accompanied by drums and cymbals. Outside the tomb, a large open space is cleared for the dervishes and the banner is raised for the ritual to begin. The pace of the chanting picks up, and the dervishes start to circle the clearing, bobbing and clapping.

The purpose of the frenzy is a ritual called dhikr. The dhikr relies on the recitation of God’s names to help create a state of ecstatic abandon in which the adherent’s heart can communicate directly with God. This personal communication with God is central to Sufi practices. The Sufis are often called ‘whirling dervishes’ but that’s really a bit of a misnomer. Most are content to parade around the circle chanting and clapping. Occasionally a dervish will break off and start twirling, spinning on one foot and lost in his own personal path to God. As they march, the dervishes repeatedly chant La illaha illallah, meaning ‘There is no God but Allah’, the first line of the Muslim profession of faith. Around the edge of the circle other adherents clap and join in the chanting, creating a highly charged and hypnotic atmosphere. The chanting can last for up to 45 minutes. At the end of the ritual, the dervishes break off and enter the mosque to pray in the orthodox Islamic manner.

With Sufism so important to Sudanese Islam, dhikr rituals like this play a major role in religious life. There is a real festival air around the dhikr. Beside the tomb there are tea stalls and adherents selling Sufi pamphlets and tapes; before the ritual starts there is often drumming and chanting inside the tomb itself, and food provided for the needy.

Photography is allowed, but it’s best to be discreet. Don’t dash into the circle to fire off a couple of shots – the dervishes use ritual and atmosphere as the centre of their ceremony, and so shouldn’t be interrupted in any way. This is an active religious community, not a tourist attraction. If in doubt, ask for permission.

To reach the tomb, go to Arabi Bus Station and ask for the minibus heading to Hamed al-Nil; the bus ride should take around 20 minutes. The onion-domes of the tomb and mosque are clearly visible from the road. Get there in plenty of time; the ritual starts around an hour before sunset on Friday. NB: The dervishes do not gather during Ramadan or Eid.

Conshelf II