The map of Tanzania is guaranteed to leave any statistician salivating. But, reading like a virtual litany of Africa’s most evocative place names, it will also touch the heart of any poet.

Philip Briggs & Chris McIntyre authors of Tanzania Safari Guide

Tanzania is Africa’s ultimate safari destination. With roughly a quarter of its area protected in a network of parks that includes the world-famous Serengeti, Tanzania is home to almost half the world’s remaining wild lions, and around one-fifth of Africa’s surviving elephants. Then there are the two million wildebeest and zebra that migrate annually through the Serengeti ecosystem, embarking on the dramatic mass calvings and chaotic river crossings that make it one of the world’s greatest wildlife spectacles.

The Serengeti alone would be sufficient to place Tanzania near the top of most travellers’ bucket lists. But Tanzania is home to several other world-class attractions. These include snow-capped Kilimanjaro (the world’s highest freestanding mountain), as well as the magical ‘spice island’ of Zanzibar, situated 25km offshore in the heart of the Indian Ocean, and parts of the three largest and most biodiverse lakes on the African continent.

Other prime wildlife sanctuaries include the Edenesque Ngorongoro Crater bordering the Serengeti, the vast sprawl of the Selous Game Reserve (a wildlife sanctuary larger than Switzerland), and the lovely Lake Manyara, set spectacularly at the base of the Great Rift Valley. Meanwhile, further west, on the remote shore of the world’s longest freshwater lake, Gombe Stream – the former stamping ground of Jane Goodall – and Mahale Mountains vie with each other as the top chimp tracking destinations in Africa.

For more information, check out our guide to Tanzania

Food and drink in Tanzania

Most tourists will eat 90% of their meals at game lodges or hotels that cater specifically to tourists and whose kitchens serve Western-style food, ranging in standard from adequate to excellent. Game lodges tend to offer a daily set menu with a limited selection, so it is advisable to have your tour operator specify in advance if you are a vegetarian or have other specific dietary requirements. First-time visitors to Africa might take note that most game lodges in and around the national parks have isolated locations, and driving within the parks is neither permitted nor advisable after dark, so that there is no realistic alternative to eating at your lodge. You will rarely be disappointed.

Most game lodges offer the option of a packaged breakfast and/or lunch box, so that their guests can eat on the trot rather than having to base their game-viewing hours around set meal times. The standard of the packed lunches is rather variable (and in some cases pretty awful) but if your first priority is to see wildlife, then taking a breakfast box in particular allows you to be out during the prime game-viewing hours immediately after sunrise. Packed meals must be ordered the night before you need them. It is best to ask your driver-guide to make this sort of arrangement, rather than doing it yourself.

When you are staying in towns such as Arusha and Moshi, there is a fair selection of eating-out options. Indian eateries are particularly numerous in most towns, thanks to the high resident Indian population, and good continental restaurants and pizzerias are also well represented. Seafood is excellent on the coast. Options tend to be more limited in smaller towns such as Lushoto or Tanga, and very basic in villages off the main tourist trail.

As for the local cuisine, it tends to consist of a bland stew eaten with one of four staples: rice, chapati, ugali or batoke. Ugali is a stiff maize porridge eaten throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Batoke or matoke is cooked plantain, served boiled or in a mushy heap. In the Lake Victoria region, batoke replaces ugali as the staple food. The most common stews are chicken, beef, goat and beans, and the meat is often rather tough. In coastal towns and around the great lakes, whole fried fish is a welcome change. The distinctive Swahili cuisine of the coast makes generous use of coconut milk and is far more spiced than other Tanzanian food.

Mandaazi, the local equivalent of doughnuts, are tasty when freshly cooked. They are served at hotelis and sold at markets. You can eat cheaply at stalls around markets and bus stations. Goat kebabs, fried chicken, grilled groundnuts and potato chips are often freshly cooked and sold in these places. A very popular and filling (though not exactly healthy) street dish throughout Tanzania is chipsi mayai, which essentially consists of potato chips cooked in an omelette-like mix of eggs (mayai).

Health and safety in Tanzania

Health

Tanzania, like most parts of Africa, is home to several tropical diseases unfamiliar to people living in more temperate and sanitary climates. However, with adequate preparation, and a sensible attitude to malaria prevention, the chances of serious mishap are small. To put this in perspective, your greatest concern after malaria should not be the combined exotica of venomous snakes, stampeding wildlife, gun-happy soldiers or the Ebola virus, but something altogether more mundane: a road accident.

Private clinics, hospitals and pharmacies can be found in most large towns, and doctors generally speak good English. Consultation fees and laboratory tests are inexpensive when compared with most Western countries, so if you do fall sick, don’t allow financial considerations to dissuade you from seeking medical help. Commonly required medicines such as broad-spectrum antibiotics, painkillers, asthma inhalers and various antimalarial treatments are widely available. If you are on any short-term medication prior to departure, or you have specific needs relating to a less common medical condition (for instance if you are allergic to bee stings or nuts), then bring necessary treatment with you.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on www.istm.org. For other journey preparation information, consult www.travelhealthpro.org.uk (UK) or http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ (US). Information about various medications may be found on www.netdoctor.co.uk/travel. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Crime exists in Tanzania as it does practically everywhere in the world. There has been a marked increase in crime in Tanzania over recent years, and tourists are inevitably at risk because they are far richer than most locals, and are conspicuous in their dress, behaviour and (with obvious exceptions) skin colour. For all that, Tanzania remains a lower crime risk than many countries, and the social taboo on theft is such that even a petty criminal is likely to be beaten badly should they be caught in the act.

With a bit of care, you would have to be unlucky to suffer from more serious crime while you are in Tanzania. Indeed, a far more serious concern is reckless and drunk driving, particularly on public transport along major roads. Generally buses are regarded to be safer than light vehicles such as minibuses, though this cannot be quantified statistically. Safari drivers are generally a lot more sedate and safe behind the wheel than bus and minibus drivers. Self-drivers should take a far more defensive attitude to driving than they would at home, and be alert to the road hog mentality of many local drivers.

Female travellers

Women travellers in Tanzania have little to fear on a gender-specific level. Over the years, I’ve met several women travelling alone in Tanzania, and none had any serious problems in their interactions with locals, aside from the hostility that can be generated by dressing skimpily. Otherwise, an element of flirtation is about the sum of it, perhaps the odd direct proposition, but nothing that cannot be defused by a firm ‘No’. And nothing for that matter that you wouldn’t expect in any Western country, or – probably with a far greater degree of persistence – from many male travellers.

It would be prudent to pay some attention to how you dress in Tanzania, particularly in the more conservative parts of the Swahili coast. In areas where people are used to tourists, they are unlikely to be deeply offended by women travellers wearing shorts or other outfits that might be seen to be provocative. Nevertheless, it still pays to allow for local sensibilities, and under certain circumstances revealing clothes may be perceived to make a statement that’s not intended from your side.

Travel and visas in Tanzania

Visas for Tanzania

Visas are required by most visitors to Tanzania, including UK and US passport holders, and cost US$30–60, depending on your nationality. Visas can be obtained on arrival at any international airport, or at any border post. This is a straightforward procedure: no photographs or other documents are required, but the visa must be paid for in hard currency.

The visa is normally valid for three months after arriving in the country, and it allows for multiple crossings into Uganda and Kenya during that period. Note, however, that the regional East African travel visa that can be issued by Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda, and that allows freedom of movement between these three countries, does not include Tanzania.

Getting there and away

By air

There are two international airports on the Tanzanian mainland. Julius Nyerere International Airport in Dar es Salaam (airport code DAR) is the traditional point of entry for international airlines, and it is generally convenient for business travellers but less so for tourists; many visitors who arrive in Dar transfer directly on to a flight to elsewhere in the country.

The more useful point of entry for most tourists is Kilimanjaro International Airport (often abbreviated to KIA although its official airport code is JRO), which lies midway between Moshi and Arusha, and is now used by several international airlines.

Budget travellers looking for flights to East Africa may well find it cheapest to use an airline that takes an indirect route. London is a good place to pick up a cheap ticket; many continental travellers buy their tickets there.

It is generally cheaper to fly to Nairobi than to Dar es Salaam, and getting from Nairobi to Arusha by shuttle bus is cheap, simple and quick. Several airlines also operate daily flights between Nairobi and Kilimanjaro International Airport.

Getting around

By air

Several private airlines run scheduled flights around Tanzania, most prominently Fastjet, Regional Air Services, Precision Air, Coastal Aviation, Auric Air and Zanair. Between them, these carriers offer reliable services to most parts of the country that regularly attract tourists, including Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar, Pemba, Mafia, Kilimanjaro, Arusha, Serengeti, Ngorongoro, Lake Manyara, Mwanza, Rubondo Island, Kigoma and most of the southern parks.

There are also regular flights between Kilimanjaro and the Kenyan cities of Mombasa and Nairobi. Several of the airlines now offer a straightforward online booking service.

The main carriers for the southern safari circuit are Coastal Travel and Safari Airlink, and the latter also operates scheduled flights to Katavi and Mahale. Auric Air is the only carrier servicing several relatively obscure destinations, for instance Mpanda, Mbeya, Tabora and Kigoma.

By public transport

Good express coach services, typically travelling at faster than 60km/h, connect Arusha and Moshi to Dar es Salaam and Nairobi (Kenya). Dar and Kilimanjaro Express are particularly recommended, approaching (although far from attaining) Greyhound-type standards, and they operate several buses daily between Dar es Salaam and Arusha. Express coaches also connect Arusha to Moshi, Lushoto, Tanga, Mwanza and Dar es Salaam.

For long trips on major routes, ensure that you use an ‘express bus’, which should travel directly between towns, stopping only at a few prescribed places, rather than stopping wherever and whenever a potential passenger is sighted or an existing passenger wants to disembark.

Be warned that as far as most touts are concerned, any bus that will give them commission is an express bus, so you are likely to be pressured into getting on to the bus they want you to get on. The best way to counter this is to go to the bus station on the day before you want to travel, and make your enquiries and bookings in advance, when you will be put under less pressure and won’t have to worry about keeping an eye on your luggage.

The alternative to buses on most routes is a dalla-dalla – a generic name that seems to encompass practically any light public transport. On the whole, dalla-dallas tend to be overcrowded by comparison with buses, and they are more likely to try to overcharge tourists, while the manic driving style results in regular fatal accidents.

By private safari and car rental

The most normal way of getting around Tanzania is on an organised safari by Land Cruiser, Land Rover or any other similarly hardy 4×4 with high clearance.

It is standard procedure for safari companies to provide a driver/guide with a fair knowledge of local wildlife and road conditions, as well as some mechanical expertise. If you want to view and compare sample itineraries, please see the listing of Tanzania safari tours on SafariBookings. This comparison website lists tours offered by both local and international tour operators.

Self-drive car hire isn’t a particularly attractive or popular option in northern Tanzania, but it is widely available in Zanzibar and Dar es Salaam.

When to visit Tanzania

Tourist arrivals to Tanzania are highest during the northern hemisphere winter, but the country can be visited throughout the year, since every season has different advantages, depending strongly on which parts of the country you plan to include in your itinerary.

Northern safari circuit

April and May are usually the wettest months in northern Tanzania, and thus the quietest time of the year in touristic terms. This has its advantages. For one, most lodges and camps offer significantly cheaper low-season rates, which can greatly reduce the cost of a safari. And there is nothing wrong with the game viewing: plenty of wildlife can be seen in the south-central Serengeti over April and May, while the Ngorongoro Crater and Lake Manyara, which are incorporated into most northern safaris, are not so strongly seasonal in terms of wildlife movements, but they are far less crowded with 4x4s and more enjoyable to visit outside of peak tourist seasons.

Southern safari circuits

The parks of the south and west have a more clearly defined seasonal character than their northern counterparts. The best time to visit Selous, Ruaha, Mikumi and Katavi is during the long dry season, which runs from June to October or early November. This is when wildlife is most easily spotted as it congregates around perennial water sources, and also when road conditions are best, and the risk of contracting malaria is lowest.

Late November to early March sees showers, especially in the first two months. This makes wildlife more difficult to locate, but the scenery tends to be greener and avian activity peaks as migrant birds arrive from the northern hemisphere and resident birds go into breeding plumage. Late February to the end of May is best avoided, and roads are often washed out – indeed many camps and lodges in the south close for some or all of this period. Chimp tracking in Mahale and Gombe is also best during the dry season, though Gombe in particular could be visited at any time of year.

Mount Kilimanjaro and Meru

Trekking conditions are best in the dry seasons, which run from January to early March and from August to October. There are several advantages to the period January to early March. The first is that it tends to be quieter in terms of tourists, an important consideration if you are following one of the more popular routes. The second is that it is probably the most beautiful time of year to climb, with the best chance of clear skies at higher altitudes. On the downside, it is also the coldest time of year on the mountain, though this does mean the snow cap tends be more extensive than in warmer months. The worst months for climbing in terms of weather are November and December.

Zanzibar and the coast

The coast can be visited throughout the year. However, the most pleasant time to be there is the long dry season, which runs from June to October. Th is is when temperatures are most comfortable (though still hot by European standards) and the humidity is lowest. Th ere is also less chance of your holiday being disrupted by rain, and it is considerably safer than the wet season in terms of malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases. The wettest months of April and May are best avoided, while January to March, though drier, tend to be hot.

What to see and do in Tanzania

Kilwa Kisiwani

Separated from Kilwa Masoko by a 2km-wide channel, Kilwa Kisiwani is the one must-see attraction around Kilwa, and for most non-anglers, the main reason for visiting the area in the first place. Immortalised as the Quiloa of Milton’s Paradise Lost, and once thought to be the site of King Solomon’s mythical mines, the abandoned city – with its haunted mosques, derelict palaces and lonesome monsoon-swept tombs – is the most important surviving relict of the Islamic-influenced Swahili maritime trade that dominated the coast from early medieval times until the arrival of the Portuguese, who sacked the city in 1505, a defeat from which it never recovered, despite several later reoccupations.

Kondoa Rock Art Sites

Inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006, the prehistoric rock art that adorns the Maasai Escarpment south of Tarangire is the most intriguing outdoor gallery of its sort in East Africa, and among the most ancient and stylistically varied anywhere on the continent. Although it extends over an area of 2,350km², the best-known panels are centred around the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it village of Kolo, which straddles the Arusha–Dodoma road between Kondoa and Babati.

The rock art around Kolo and Kondoa is the most prolific in equatorial Africa. This is partly due to the lay of the land. Like the equally rich uKhahlamba- Drakensberg region in South Africa, Kondoa is endowed with numerous granite outcrops tailor-made for painting. The major rock art panels here are generally sited within small caves or beneath overhangs aligned to an east–west axis, a propensity that might reflect the preferences of the artists, or might have provided the most favourable conditions for preservation against the elements. The age of the paintings is tentatively placed at between 200 and 4,000 years, but their intent is a matter of speculation.

Embark on a canoe safari at Lake Manyara © Ariadne Van Zandbergen, Africa Image Library

Lake Manyara National Park

A popular first port of call on any northern Tanzanian safari, Lake Manyara National Park is named after its dominant geographic feature, a shallow, alkaline lake set at the base of the tall wooded cliffs of the western Rift Valley Escarpment. This scenic sanctuary protects the lake’s northwestern shore, along with a diversity of terrestrial habitats that seems truly remarkable considering that water comprised up to twothirds of the park’s surface area of 330km² (prior to the recent incorporation of the largely inaccessible 250km² Marang Forest Reserve). Lake Manyara National Park has long been touted as the best place in Tanzania to see tree-climbing lions, an accolade that now more accurately belongs to the Serengeti, but more reliable highlights include the large habituated baboon troops, often accompanied by blue monkeys, that inhabit the groundwater forest close to the entrance gate, and a hippo pool that also offers some great aquatic birdwatching.

Only one (very exclusive) permanent lodge stands within the park boundaries, but several decent upmarket lodges run along the escarpment overlooking the lake, while a selection of cheaper lodgings and campsites is centred on the village of Mto wa Mbu near the entrance gate. Although Manyara and its well-defined game-viewing circuit kick off a high proportion of safaris through northern Tanzania, it gets mixed feedback: some find it rather low-key and boring compared with the Serengeti and Ngorongoro, while others relish the opportunity to see several species that are less common or shyer elsewhere in the region. Certainly, those with strong time or budgetary restrictions might want to consider passing over Manyara in favour of spending more time in other reserves.

Mahale Mountains National Park

Scenically reminiscent of Gombe Stream but on a far grander scale, the 1,613km² Mahale Mountains is quite simply one of the most beautiful national parks anywhere in Africa, and it also ranks as arguably the top chimpanzee-tracking destination anywhere on the continent. Some 30 times larger than Gombe, the park occupies a mountainous knuckle that juts into Lake Tanganyika some 150km south of Kigoma.

It is dominated topographically by the Mahale Range, a stretch of the Rift Valley Escarpment that rises sharply from the lakeshore to the 2,462m Nkungwe Peak, and six other peaks that exceed 2,000m in elevation. Even without the forested peaks, the crystal-clear waters and deserted sandy beaches that characterise this part of Lake Tanganyika would be thoroughly alluring, but as it is, the setting is scenically reminiscent of a volcanic island beach resort somewhere deep in the Indian Ocean – with the added bonus that these forests are inhabited by a rich variety of birds and primates, including an estimated 1,000 chimpanzees divided across a dozen communities including the habituated Mimikere group of around 60 individuals.

Mount Kilimanjaro

Reaching an altitude of 5,895m (19,340ft), Kilimanjaro is the highest mountain in Africa, and on the rare occasions when it is not veiled in clouds, its distinctive silhouette and snow-capped peak form one of the most breathtaking sights on the continent. There are, of course, higher peaks on other continents, but Kilimanjaro is effectively the world’s largest single mountain, a free-standing entity that towers an incredible 5km above the surrounding plains. It is also the highest mountain anywhere that can be ascended by somebody without specialised mountaineering experience or equipment.

Kilimanjaro straddles the border with Kenya, but the peaks all fall within Tanzania and can only be climbed from within the country. There are several places on the lower slopes from where the mountain can be ascended, but most people use the Marangu Route (which begins at the eponymous village) because it is the cheapest option and has the best facilities.

The less heavily trampled Machame Route, starting from the village of the same name, has grown in popularity in recent years. A number of more obscure routes can be used, though they are generally only available through specialist trekking companies. Most prospective climbers arrange their ascent of ‘Kili’ – as it is popularly called – well in advance. SafariBookings is a good place to start if you want to view and compare Kilimanjaro climbing tours online, but you can also shop around on the spot using specialist trekking companies based in Moshi, Marangu or even Arusha. Kilimanjaro can be climbed at any time of year, but the hike is more difficult in the rainy months, especially between March and May.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area

Inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and listed as an International Biosphere Reserve, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA) extends over 8,292km² to the southeast of the Serengeti National Park, with which it shares a border of roughly 80km. Its dominant feature is the geological marvel known as the Ngorongoro Crater – the world’s largest intact volcanic caldera, and a shoo-in contender for any global shortlist of natural wonders thanks to its gobsmacking scenic beauty and the wildlife that teems across its verdant 260km² floor.

The rest of the NCA can be divided into two distinct parts. The eastern Crater Highlands comprise a sprawling volcanic massif studded with craggy peaks and gaping craters, while the lower-lying western plains are essentially a continuation of the Serengeti ecosystem, supporting a cover of short grass that attracts immense concentrations of grazers during the rainy season.

Ruaha National Park

One of East Africa’s most biodiverse and rewarding safari destinations, Ruaha also now ranks as the largest national park in Tanzania, protecting a wild 20,220km² tract of wooded rocky slopes, open plains and seasonal wetlands that drain into the Great Ruaha River. Famed for its large numbers of elephant, which are still substantial despite recent poaching, Ruaha only ranks a short way behind the Serengeti-Mara when it comes to lion and other big cat sightings, and it is one of the few places anywhere on the continent to a support a viable population of the endangered African wild dog.

Other attractions include an unusually varied selection of ungulates, and some excellent birdwatching. But above all, perhaps, it is Ruaha’s wild and untrammelled feel that sets it apart, and that has made it the favourite of many regular East African safari-goers. This wilderness feel is reflected in the park’s limited accommodation, which comprises half-a-dozen small and exclusive permanent camps and a few semi-permanent ones, scattered far more widely than their counterparts in Selous. Ruaha’s remote location – more than 600km from Dar es Salaam, including a rough and dusty 100km drive west from Iringa – means than the overwhelming majority of visitors fly in to one of these camps, which generally offer all-inclusive upmarket packages incorporating expertly guided game drives and in some cases guided walks.

But Ruaha is also becoming a popular target for more budget-conscious travellers thanks to a proliferation of small lodges that lie between the main entrance gate and Tungamalenga 18km to its east and offer day safaris into the park. Ruaha is best visited between July and November, when animals concentrate around the river. Internal roads may be impassable towards the end of the rainy season (March to May).

Selous Game Reserve

The largest game reserve anywhere in Africa, the 47,500km² Selous extends over thrice the area of Serengeti National Park, and is roughly 50% bigger than either Belgium or Swaziland. It forms the core of Africa’s largest remaining tract of comparably untrammelled bush, the 155,000km² Greater Selous–Niassa ecosystem, which also incorporates Mikumi and Udzungwa national parks, Kilombero Game Protected Area, and Mozambique’s 23,400km² Niassa Game Reserve.

Bisected by the life-sustaining Rufiji River, this vast area of dry woodland supports what are probably the world’s largest surviving populations of buffalo, hippo and lion (estimated at around 150,000, 40,000 and 4,000 respectively), and it is also the most important global stronghold for the endangered African wild dog. As recently as the turn of the millennium, the Greater Selous was also home to around 70,000 elephants, some 10% of the continental total, but a tragic onslaught of commercial poaching has since reduced the population to around 15,000.

Much of the publicity surrounding the Selous hammers on about its vast area, but this is something of a red herring in touristic terms. True, this vast reserve does attract a mere fraction of the tourist arrivals associated with the northern safari circuit. And accommodation is indeed limited to a dozen-or-so low-key camps thatespouse an eco-friendly philosophy and thatch-and-canvas aesthetic, and whose combined bed capacity amounts to a few hundred clients. Yet a quick glace at a map will reveal that these tourist facilities are all compressed within a relatively small public sector to the north of the Rufiji, a reserve-within-a-reserve that accounts for less than 5% of the Selous’s total surface area (with the other 95% carved into private hunting concessions). As a result, the ‘multiple vehicles looking for the same lion pride’ phenomenon is more common in Selous than some would have you believe, especially in the area closest to the Mtemere Gate.

For all that, the public part of the Selous is wonderfully atmospheric, a dense tract of miombo wilderness dominated by the compelling presence of the wide palm-lined Rufiji River and an associated labyrinth of interconnected lakes and channels. Arriving by light aircraft, as most visitors do, you’ll sweep exhilaratingly above green-fringed channels teeming with hippos and waterfowl, swampy islets grazed by immense herds of elephant and giraffe, and exposed sandbanks full of drinking antelope and sleeping crocodiles.

And once there, while the variety of large mammals likely to be seen is limited by comparison with, say, the Serengeti or Ruaha, an unusually wide range of activities – guided bush walks, fly-camping around the lakes, and above all thrilling boat trips on the Rufiji – create a far more integrated bush experience than the repetitive regime of two daily game drives typical of other Tanzanian national parks. Be warned, however, that Selous’s wilderness character, and the exposed nature of its rustic camps and lodges, means it is probably better suited to experienced safari-goers than to nervous neophytes.

The great wildebeest migration passes through the Serengeti between December and April © Ariadne Van Zandbergen, Africa Image Library

Serengeti National Park

The great wildebeest migration passes through the Serengeti between December and April © Ariadne Van Zandbergen, Africa Image Library Tanzania’s oldest, largest and most famous national park, the 14,763km² Serengeti is the centrepiece of a twice-larger ecosystem that also incorporates the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, several smaller Tanzanian wildlife reserves, and the Maasai Mara in neighbouring Kenya.

Home to unusually dense populations of lions and other predators, the Serengeti is probably the leading contender for the accolade of Africa’s finest game-viewing destination, renowned above all for the annual migration of millions of wildebeest and other ungulates across its vast plains. And while sceptics might fear that such a heavily hyped icon is unlikely to match expectations, our experience over more than a dozen safaris is that the Serengeti seldom disappoints: the variety and volume of its wildlife truly is second to none, as is the liberating sense of space attached to exploring its immense plains.

Tarangire National Park

The 2,850km² Tarangire National Park lies at the core of a 20,000km² semi-arid ecosystem that also incorporates several more-or-less contiguous Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) created since 2006 in consultation with local communities. These are the Randileni WMA to the north, the Levolosi WMA to the northwest, the Burunge WMA running west towards Lake Manyara, and the vast but undeveloped 5,372km² Makame WMA extending southwards across the Maasai Steppes.

Inherently drier than the Serengeti, and less well publicised, Tarangire National Park is nevertheless a highly rewarding wildlife destination, especially during the latter half of the year, when it’s a recommended inclusion on any safari itinerary of a week or longer. The park is best known for its year-round proliferation of elephants, but predators are also well represented, the birdlife is consistently rewarding, and large herds of migrant grazers are drawn to the perennial water of the Tarangire River when other sources dry up.

More information

For more information, see our guide to Tanzania:

Related articles

Welcome to the ultimate safari destination.

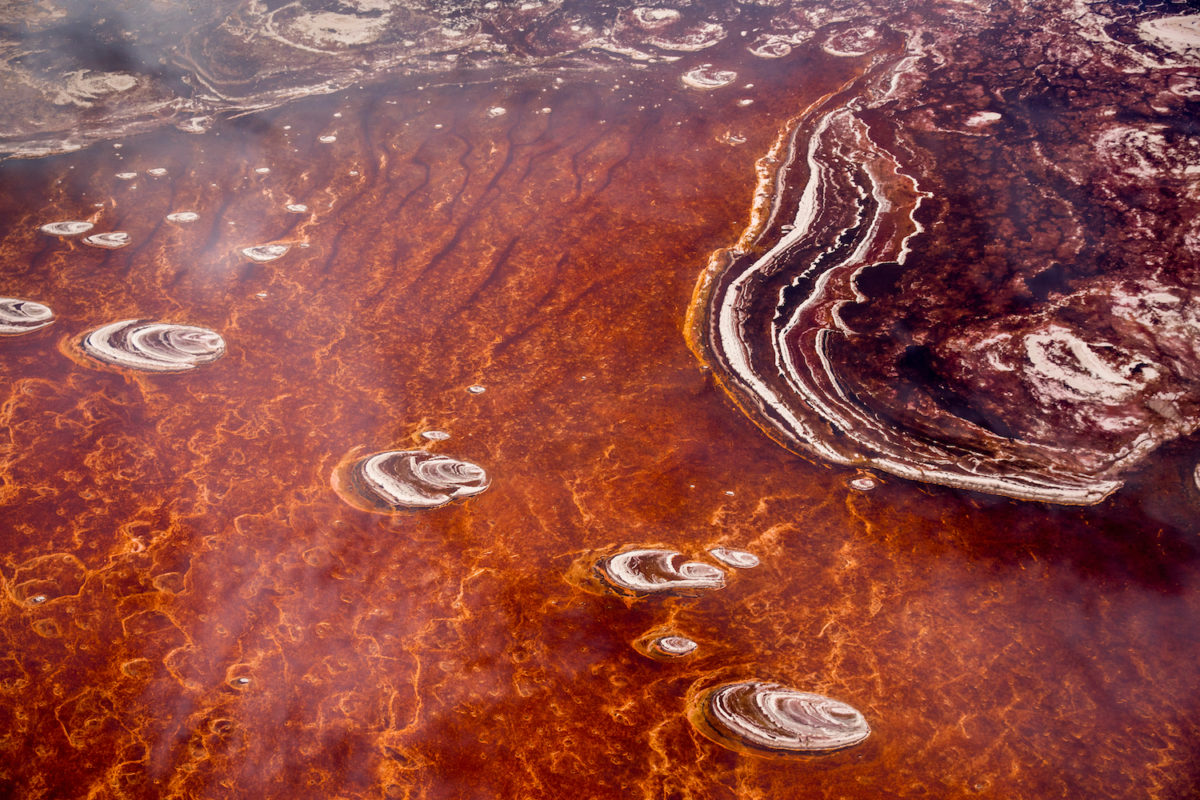

Seemingly inhospitable by all accounts, except for the few million flamingos that flock to its waters every year. Intrigued?

Our pick of the best national parks to visit in Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda.

How many have you visited?

Sit back and enjoy this kaleidoscope of colours.

Exploring one of Africa’s most beautiful countries – without the tourists.

How many of these have you climbed?