Ugandans as a whole – both those working within the tourist industry and the ordinary man or woman on the street – genuinely do come across as the most warm, friendly and relaxed hosts imaginable.

Philip Briggs & Andrew Roberts, authors of Uganda: the Bradt Guide

Uganda is one of our hot destinations for the year ahead – check out the full list of the best places to travel in 2024 here.

What other country can match Uganda for sheer variety? Within a compact area of 241,000km2 – almost exactly the same as United Kingdom – you’ll find an unparalleled array of wildlife, scenery and cultures.

For Uganda is where east meets west in Africa. East African savannahs roamed by big game favourites merge with Congo-style rainforests bristling with primates (including mountain gorilla, golden monkey and chimpanzee) and birds (many associated with the Congo forests and found nowhere else in East Africa).

To these broad themes we can add local detail – wetlands, woodlands, mountains, and lakes of all sizes – to produce a mosaic of natural habitats that support, in total, 342 mammal species and 1,008 of bird.

Ugandan culture further reflects this diversity of landscapes; in the remote northeast you’ll find lanky pastoralists tending their herds on the vast plains of Karamoja while in the mountainous west you’ll meet stocky Bakiga and Bakonzo cultivating steep hillsides, and learn about traditional forest life from the diminutive Batwa Pygmies.

Whatever your area of interest, Uganda abounds in unforgettable activities and encounters. You can track chimpanzees and mountain gorillas in the depths of tropical forests; search for tree-climbing lions on the open Ishasha plains; descend into the hot depths of the Western Rift Valley in search of rare birdlife; fish for a record Nile Perch on the island-studded expanse of Lake Victoria; raft the turbulent headwaters of the Nile and marvel at the great river’s eruption through a 6m canyon at Murchison Falls; visit a traditional homestead on the remote plains of Karamoja; and feel the chill of equatorial snow on the 5,100m Rwenzori Mountains.

For more information, check out our guide to Uganda

Food and drink in Uganda

Eating out

If you are not too fussy and don’t mind a lack of variety, you can eat cheaply almost anywhere in Uganda. In most towns numerous local restaurants (often called hotelis) serve unimaginative but filling meals for under US$2. Typically, local food is based around a meat or chicken stew eaten with one of four staples: rice, chapati, ugali or matoke. Ugali is a stiff maize porridge eaten throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Matoke is a cooked plantain dish, served boiled or in a mushy heap, and the staple diet in many parts of Uganda. Another Ugandan special is groundnut sauce. Mandazi, the local equivalent of doughnuts, are tasty when they are freshly cooked, but rather less appetising when they are a day old. Mandazi are served at hotelis and sold at markets. You can often eat very cheaply at stalls around markets and bus stations.

Cheap it may be, but for most travellers the appeal of this sort of fare soon palls. In larger towns, you’ll usually find a couple of better restaurants (sometimes attached to upmarket or moderate hotels) serving Western or Indian food for around US$5–8. There is considerably more variety in Kampala, where for US$10–12 per head you can eat very well indeed. Upmarket lodges and hotels generally serve high-quality food. Vegetarians are often poorly catered for in Uganda (the exception being Indian restaurants), and people on organised tours should ensure that the operator is informed in advance about this or any other dietary preference.

Cooking for yourself

The alternative to eating at restaurants is to put together your own meals at markets and supermarkets. The variety of foodstuffs you can buy varies from season to season and from town to town, but in most major centres you can rely on finding a supermarket that stocks frozen meat, a few tinned goods, biscuits, pasta, rice and chocolate bars. Fruit and vegetables are best bought at markets, where they are very cheap. Potatoes, sweet potatoes, onions, tomatoes, bananas, sugarcane, avocados, paw-paws, mangoes, coconuts, oranges and pineapples are available in most towns. For hikers, packet soups and noodles are about the only dehydrated meals that are available throughout Uganda. If you have specialised requirements, you’re best off doing your shopping in Kampala, where a wider selection of goods is available in the supermarkets.

Drinks

The usual brand-name soft drinks are widely available in Uganda and cheap by international standards. You can buy imported South African fruit juices at supermarkets in Kampala and other large towns. Tap water is reasonably safe to drink in larger towns, but bottled mineral water is widely available if you prefer not to take the risk.

Locally, the most widely drunk hot beverage is chai, a sweet tea where all ingredients are boiled together in a pot. In some parts of the country chai is often flavoured with spices such as ginger (an acquired taste, in the author’s opinion). Coffee is one of Uganda’s major cash crops, but brewed locally it almost invariably tastes insipid and watery, except at upmarket hotels and restaurants, and specialist coffee shops.

The main alcoholic drink is lager beer, and several brands are available. Most come in 500ml bottles, which cost around US$1.50 in local bars and up to US$4 in some upmarket hotels. Nile Special is probably the most popular tipple with locals and travellers alike, though after a few experiments, many opt for the milder Club and Bell. If you’ve never been to Africa before, you might want to try the local millet beer. It’s not bad, though for most people once is enough.

A selection of superior plonk-quality South African wines is available in most tourist-class hotels and bars, as well as in some supermarkets, generally starting at around US$10–20 per bottle. Local gins can be bought very cheaply in a variety of bottle sizes or in 60ml sachets – very convenient for hiking in remote areas or taking with you to upmarket hotels for an inexpensive nightcap in your room. These are known by the rather endearing term ‘tot pack’, though the African fondness for tacking an additional vowel to the end of a noun has actually resulted in ‘totter pack’; you may appreciate this inadvertent irony if you overindulge.

Health and safety in Uganda

Health

Uganda, like most parts of Africa, is home to several tropical diseases unfamiliar to people living in more temperate and sanitary climates. However, with adequate preparation and a sensible attitude to malaria prevention, the chances of serious mishap are small. To put this in perspective, your greatest concern after malaria should not be the combined exotica of venomous snakes, stampeding wildlife, gun-happy soldiers or the Ebola virus, but something altogether more mundane: a road accident.

Private clinics, hospitals and pharmacies can be found in most large towns, and doctors generally speak good English. Consultation fees and laboratory tests are inexpensive when compared with most Western countries, so if you do fall sick, don’t allow financial considerations to dissuade you from seeking medical help. Commonly required medicines such as broad-spectrum antibiotics, painkillers, asthma inhalers and various antimalarial treatments are widely available over the counter. If you are on any short-term medication prior to departure, or you have specific needs relating to a less common medical condition (for instance if you are allergic to bee stings or nuts), then bring necessary treatment with you. Sensible preparation will go a long way to ensuring your trip goes smoothly. The Bradt website now carries a health section online to help travellers prepare for their African trip.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available. For other journey preparation information, consult Travel Health Pro (UK) or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA). Information about various medications may be found on Net Doctor. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Uganda has been an acceptably safe travel destination since Museveni took power in 1986. The only region that subsequently experienced long-term instability is the north, but even that has settled down since 2006. Kampala, like most cities around the world, is vulnerable to terrorist attacks, as demonstrated in 2010 when 74 people were killed in twin blasts at two venues showing World Cup matches on television. More recently, in what was hopefully a one-off incident in April 2019, an American tourist and local driver were kidnapped at gunpoint during a game drive in the Ishasha Sector of Queen Elizabeth National Park; both were rescued unharmed a few days later after the Ugandan government reputedly paid a portion of the demanded ransom. Despite this, however, the most significant threat to life and limb in Uganda comes not from banditry or terrorism, but rather from the malaria parasite and car, boda or boat accidents.

Theft

Uganda is widely and rightly regarded as one of the most crime-free countries in Africa, certainly as far as visitors need be concerned. Muggings are comparatively rare, even in Kampala, and it is largely free of the sort of con tricks that abound in places like Nairobi. Even petty theft such as pickpocketing and bag snatching is relatively unusual, though it does happen from time to time. Walking around large towns at night is reputedly safe, though it would be tempting fate to wander alone along unlit streets. On the basis that it is preferable to err on the side of caution, a few tips that apply to travelling anywhere in East and southern Africa:

• Most casual thieves operate in busy markets and bus stations. Keep a close watch on your possessions in such places, and avoid having valuables or large amounts of money loose in your daypack or pocket.

• Keep all your valuables and the bulk of your money in a moneybelt that can be hidden beneath your clothing. A belt made of cotton or another natural fabric

is most pleasant on the skin, but such fabrics tend to soak up sweat, so wrap everything inside in plastic. Never show this moneybelt in public, and keep any spare cash you need elsewhere on your person.

• Where the choice exists between carrying valuables on your person or leaving them in a locked room, we would generally favour the latter option, though you need to use your judgement and be sure the room is absolutely secure.

• Leave any jewellery of financial or sentimental value at home.

Female travellers

Women generally regard sub-equatorial Africa as one of the safest places in the world to travel alone. Uganda in particular poses few if any risks specific to female travellers. It is reasonable to expect a fair bit of flirting and the odd direct proposition, especially if you mingle with Ugandans in bars, but a firm ‘no’ should be enough to defuse any potential situation. And, to be fair to Ugandan men, you can expect the same sort of thing in any country, and for that matter from many male travellers. Ugandan women tend to dress conservatively. It will not increase the amount of hassle you receive if you avoid wearing clothes that, however unfairly, may be perceived to be provocative, and it may even go some way to decreasing it.

More mundanely, tampons are not readily available in smaller towns, though you can easily locate them in Kampala, Entebbe and Jinja, and in game lodge and hotel gift shops. When travelling in out-of-the-way places, carry enough tampons to see you through to the next time you’ll be in a large city, bearing in mind that travelling in the tropics can sometimes cause heavier or more irregular periods than normal. Sanitary pads are available in most towns of any size.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Homosexual activity is illegal in Uganda, and has been since colonial times. In 2009, existing anti-homosexuality laws were amplified by the submission to parliament of a draconian, so-called ‘Kill the Gays’ bill that caused a furore in the international community, and led to threats of withdrawal of aid and the like. The Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) was eventually passed in February 2014, albeit in a moderated form (with life imprisonment replacing the death sentence). In reality, the AHA contained little that was not already tackled under Ugandan law; its content being little more than a populist repackaging of existing legislation imposed during an era when British attitudes to gay activity were considerably less liberal than today. The AHA was overturned by the Supreme Court on 8 August 2014 and a pioneering Gay Pride rally was held outside Kampala in 2015 on the first anniversary of this ruling. Any thoughts that this represented a more enlightened stance on homosexuality were, however, crushed in August 2016, when police officers set upon the second Gay Pride rally, beating several participants and arresting 16. Subsequent Gay Pride marches have been cancelled due to threats of similar police intervention.

There is no denying the reality that the AHA saga reflected a deep-held and often vociferous anti-gay sentiment among the general populace of Uganda (93% of which believes that homosexual lifestyles are immoral and should not be socially acceptable, according to the Pew Global Attitudes Project of 2014). This prejudice has been fuelled partly by the vitriolic outpourings of right-wing American evangelists, but it also reflects a widespread perception throughout Africa that homosexuality (unlike American evangelism, or more conventional Christianity for that matter) is an un-African activity introduced by foreigners to fulfil a Western agenda. None of this, though, should provide a practical obstacle to gay and lesbian travellers visiting Uganda, provided they are willing to be discreet about their sexuality. Some, however, might well regard it to be an ethical stumbling block.

Travel and visas in Uganda

Visas

Nationals of most countries require a visa in order to enter Uganda. An e-visa can be applied for online at least five working days before the intended dates of travel, and will usually be approved within three working days of application. When the e-visa system was implemented in 2016, a statement was issued to the effect that it would completely replace the Visa on Arrival (VoA) system, but this has yet to happen. So as things stand, you can still buy a VoA at any overland border or at Entebbe International Airport, a straightforward procedure that usually takes no more than a few minutes, except perhaps when a couple of major airlines arrive within an hour of each other. These things can change, however, so check the situation before you travel, either with your travel agent or at a Ugandan diplomatic mission, or keep an eye on our updates site.

A standard single-entry visa, valid for 90 days, costs US$50. A 90-day East African Tourist Visa, valid for Uganda, Rwanda and Kenya, is also available on arrival for US$100. Multiple-entry visas cost US$100/150/200 for a period of 12/24/36 months.

Don’t overstay your visa or the date of the immigration stamp in your passport, or you’ll be liable for a hefty fine. And note that even though you hold a threemonth visa, immigration authorities may only stamp your passport for a period of one month or less. This can be extended to three months at any immigration office in Kampala or upcountry. Irrespective of what they might tell you, there is no charge for this. In Kampala, you may be asked to provide an official letter from a sponsor or the hotel where you are staying.

For security reasons, it’s advisable to detail all your important information in one document, which you can then print out and distribute in your luggage, and/or store on a smartphone, and/or email to your webmail address and a reliable contact at home. The sort of things you want to include on this are travel insurance policy details and 24-hour emergency contact number, passport number, details of relatives or friends to be contacted in an emergency, bank and credit card details, camera and lens serial numbers, etc.

Getting there and away

By air

For obvious reasons, the most convenient means of reaching Uganda from Europe and North America is by air. An established specialist UK operator is Africa Travel, and reputable agents specialising in round-the-world tickets rather than Africa specifically are Trailfinders. Shortly before going to print in late 2019, the revived national carrier Uganda Airlines announced it intends to resume flights between Entebbe and several other cities in eastern and southern Africa.

Overland

Uganda borders five countries. Of these, many visitors cross in or out of Uganda overland from Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda, but the DRC and South Sudan are largely off-limits to casual travel. Uganda’s land borders are generally very relaxed, provided that your papers are in order.

Getting around

By air

Since few major urban centres lie more than 5–6 hours’ drive from the capital, flying has never been an option for most people, though some more upmarket safaris now use flights to cut the driving time between Murchison Falls National Park and Queen Elizabeth or Bwindi Impenetrable national parks. The only destination in Uganda that is reached by air almost as often as it is by road is Kidepo Valley National Park, since the drive up from Kampala cannot be accomplished easily in one day.

The most useful airline to travellers is Aerolink, which runs a daily return flight from Entebbe west to Semliki, Kasese, Mweya (Queen Elizabeth), Kihihi (for Ishasha and Buhoma), Kisoro, and north to Bugungu, Chobe, Pakuba and Kidepo. Fly Uganda operates thrice-weekly flights from Kajjansi Airfield near Kampala to Kihihi.

Self-drive

By African standards, Uganda’s major roads are in good condition. Decent surfaced roads radiate out from Kampala, running east to Jinja, Busia, Malaba, Tororo, Mbale and Soroti, south to Entebbe, southwest to Masaka, Mbarara and Kabale, west to Fort Portal, northwest to Hoima, north to Gulu, and northeast to Gayaza and Kayunga (and on to Jinja). Other surfaced roads connect Karuma Falls to Arua, Mbale to Sipi Falls, Masaka to the Tanzanian border, Mbarara to Ibanda, and Ntungamo to Rukungiri. Most other roads are unsurfaced and tend to be variable in condition from one season to the next, with surfaces being trickiest during the rains. Road conditions described in this guide are of necessity a snapshot of conditions at the time of research and should not be taken as gospel. When in doubt, ask local advice – if matatus are getting through, then so should any 4×4, so the taxi park is always a good place to seek current information.

The main hazard on Ugandan roads is the road hog mentality of, and risks taken by, other drivers. Matatus in particular are given to overtaking on blind corners, while coaches routinely bully their way along trunk routes at up to 120km/h, forcing drivers of smaller vehicles to keep an eye on their rear-view mirror and pull off the road to let them pass. Bearing the above in mind, a coasting speed of 80km/h in the open road is comfortable without being over cautious, and it’s not a bad idea to slow down and cover the brake in the face of oncoming traffic. In urban situations, particularly downtown Kampala, right of way essentially belongs to (s)he who is prepared to force the issue – a considered blend of defensive driving tempered by outright assertiveness is required to get through safely without becoming too bogged down in the traffic.

A peculiarly African road hazard – one frequently taken to unnecessary extremes in Uganda – is the giant sleeping policeman, or ‘speed bump’ as it’s known locally. A lethal bump might be signposted in advance, it might be painted in black-and-white stripes, or it might simply rear up without warning above the road like a macadamised wave. Other regular obstacles include weaving bicycles laden with banana clusters, as well as livestock and pedestrians blithely wandering around in the middle of the road. Piles of foliage placed in the road at a few metres’ interval warn of a broken-down vehicle. Note too that indicator lights are not used to signal an intent to turn, but are switched on when approaching oncoming traffic to suggest that following drivers should not overtake. Ugandans also display a strong aversion to switching on their headlights except in genuine darkness. In rainy, misty or twilight conditions, don’t expect to be alerted to oncoming traffic by headlights, or for that matter to expect drivers to avoid overtaking or speeding simply because they cannot see more than 10m ahead. It’s strongly recommended that you avoid driving at night on main highways altogether, but if you do, be warned that a significant proportion of vehicles lack a full complement of functional headlights, so never assume a single glow indicates a motorcycle! Another very real danger is unlit trucks that have broken down in the middle of the road.

If you decide to rent a self-drive vehicle, check it over carefully and ask to take it for a test drive. Even if you’re not knowledgeable about the working of engines, a few minutes on the road should be sufficient to establish whether it has any seriously disturbing creaks, rattles or other noises. Check the condition of the tyres (bald is beautiful might be the national motto in this regard) and that there is at least one spare, better two, both in a condition to be used should the need present itself. If the tyres are tubeless, an inner tube of the correct size can be useful in the event of a repair being required upcountry. Ask to be shown the wheel spanner, jack and the thing for raising the jack. If the vehicle is a high-clearance 4×4 make sure that the jack is capable of raising the wheel high enough to change it. Ask also to be shown filling points for oil, water and petrol and check that all the keys do what they are supposed to do – we’ve left Kampala before with a car we later discovered could not be locked! Once on the road, check oil and water regularly in the early stages of the trip to ensure that there are no existing leaks.

Ugandans follow the British custom of driving on the left side of the road, albeit somewhat loosely on occasions. The following documentation is required at all times: vehicle registration book (a photocopy is acceptable); vehicle certificate of insurance, and driving licence. Your own domestic licence is theoretically acceptable for up to three months, but in practice it’s preferable to have an international licence.

Mountain biking

Uganda is relatively compact and flat, making it ideal for travel by mountain bike. New-quality bikes are not available in Uganda so you should try to bring one with you (some airlines are more flexible than others about carrying bicycles; you should discuss this with your airline in advance). However, if you are prepared to look around Kampala, some decent secondhand bikes can be bought from a few private importers for as little as US$75: there’s a huge choice in the basement of the Energy Centre building on Market Street near Nakasero Market. Main roads in Uganda are generally in good condition and buses will allow you to take your bike on the roof, though you should expect to be charged extra for this. Minor roads are variable in condition, but in the dry season you’re unlikely to encounter any problems. Several of the more far-flung destinations mentioned in this book would be within easy reach of cyclists.

Public transport

Following the permanent suspension of most passenger rail and ferry services, public transport in Uganda essentially boils down to buses and other forms of motorised road transport. The only exceptions are the passenger/ vehicle ferry between Entebbe and the Ssese Islands and local boat services connecting fishing villages on lakes Victoria, Albert and Kyoga. It’s worth noting here that overloading small passenger boats is customary in Uganda, and fatal accidents are commonplace, often linked to the violent storms that can sweep in from nowhere during the rainy season.

Buses

Coach and bus services cover all major routes and, all things being relative, they are probably the safest form of public road transport in Uganda. On all trunk routes, the battered old buses of a few years back have been replaced or supplemented by large modern coaches that typically maintain a speed of 100km/h or faster, allowing them to travel between the capital and any of the main urban centres in western Uganda in less than five hours and generally at a cost of less than US$10.

Minibus-taxis (Matatus)

In addition to buses, most major routes are covered by a regular stream of white minibuses referred to locally as matatus or (rather confusingly) taxis. Generally, these have no set departure times, but simply leave when they are full. Matatus tend to charge slightly higher fares than buses, and the drivers tend to be more reckless, but they allow more flexibility, especially for short hops. It’s customary on most routes to pay shortly before arriving rather than on departure, so there is little risk of being overcharged provided that you look and see what other passengers are paying. A law enforcing a maximum of three passengers per row is stringently adhered to in most parts of Uganda, and seat belts are now mandatory. All minibus-taxis by law now have to have a distinctive blue-and-white band round the middle, and special hire cars have to have a black-and-white band.

Boda

One of the most popular ways of getting around in Uganda is the bicycletaxi or boda (or boda-boda in full, since they originated as a means of smuggling goods from border to border along rural footpaths). Now fitted with pillions instead of panniers, and powered by foot or by 100cc engines, they are a convenient form of suburban transport and also great for short side trips where no public transport exists. Fares are negotiable and affordable – a fraction of a US dollar in most towns. If you’re reliant on public transport it’s inevitable that you’ll use a boda at some stage, but before hopping aboard you should be aware of their poor safety record. Boda riders are invariably lacking in formal training and road safety awareness, and many also seem to be in short supply when it comes to commonsense. As a result, accidents – often fatal – are commonplace.

By all means use bodas, but do try to identify a relatively sensible-looking operator, ideally of mature years. Older riders are generally better than 16-year-old village kids with no comprehension of traffic. Tell your driver to go slowly and carefully and don’t be afraid to tell him to slow down (or even stop for you to get off) if you don’t feel safe. Officially, helmets for boda drivers and their passengers have been mandatory since 2005 but the law is rarely enforced.

Though boda muggings are largely confined to Kampala, we have heard reports of similar incidents at night in Fort Portal. Presumably it could happen elsewhere, too, so keep your wits about you.

When to visit Uganda

Climate

Uganda’s equatorial climate is significantly tempered by its elevated altitude. In most parts of the country, the daily maximum is between 20°C and 27°C and the minimum is between 12°C and 18°C. The highest temperatures in Uganda occur on the plains immediately east of Lake Albert, while the lowest have been recorded on the glacial peaks of the Rwenzori. Except in the dry north, where in some areas the average annual rainfall is as low as 100mm, most parts of Uganda receive an annual rainfall of between 1,000mm and 2,000mm. There is wide regional variation in rainfall patterns. In western Uganda and the Lake Victoria region it can rain at almost any time of year. As a rough guide, however, the wet seasons are from mid September to November and from March to May.

When to visit

Equator-straddling Uganda has a warm to hot climate all year through with limited temperature variations but a strongly seasonal rainfall pattern. The wettest months in most parts of the country are April, May, October and November, when camping can be unpleasant and hiking on the Rwenzori is particularly miserable. Abundant rainfall also means that large wildlife tends not to congregate conveniently around water sources in the national parks. On the other hand, landscape photographers will revel in the haze-free skies of the rainy season.

For more itineraries see the Uganda gorilla and safari holidays on SafariBookings.

What to see and do in Uganda

An adult male mountain gorilla, known as a silverback, can be up to three times as bulky as its average human counterpart © Ariadne Van Zandbergen, Africa Image Library

Gorilla tracking at Bwindi Impenetrable National Park

Uganda’s single most important tourist hotspot is the 331km² Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (BINP), which protects a rugged landscape of steep hills and valleys abutting the Congolese border south of Ishasha and north of Kisoro. Rolling eastward from the Albertine Rift Escarpment, the tangled forested slopes of Bwindi provide shelter to one of Africa’s most diverse mammalian faunas, including 45% of the global mountain gorilla population. Unsurprisingly, the main tourist activity in BINP is gorilla tracking, which was first established at the Buhoma park headquarters in 1993, but now operates out of four trailheads – the others being Ruhija, Nkuringo and Rushaga – all of which are serviced by a selection of tourist lodges. Today, 18 habituated gorilla groups can be tracked in Bwindi, a thrilling venture regarded by most who have undertaken it to be a true once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Tracking mountain gorillas in the Virungas or Bwindi ranks among the absolute highlights of African travel. The exhilaration attached to first setting eyes on a wild mountain gorilla is difficult to describe. These are enormous animals: up to three times as bulky as the average man, their size exaggerated by a shaggily luxuriant coat. Yet despite their fearsome appearance, gorillas are remarkably peaceable creatures – tracking them would be a considerably more dangerous pursuit were they possessed of the aggressive temperament of, say, vervet monkeys or baboons, or for that matter human beings. More impressive even than the gorillas’ size and bearing is their unfathomable attitude to people, which differs greatly from that of any other wild animal I’ve encountered. Anthropomorphic as it might sound, almost everybody who visits the gorillas experiences an almost mystical sense of recognition. Often, one of the gentle giants will break off from the business of chomping on bamboo to study a human visitor, soft brown eyes staring deeply into theirs as if seeking a connection – a spine-tingling wildlife experience without peer.

Gorilla tracking should not present a serious physical challenge to any reasonably fit adult whatever their age, but the hike can be tough going. Exactly how tough varies greatly, and the main determining factor is basically down to luck, specifically how close the gorillas are to the trailhead on the day you trek (1–2 hours is typical, anything from 15 minutes to 6 hours possible). Another variable is how recently it has rained, which affects conditions underfoot – June to August are the driest months and March to May are the wettest. The effects of altitude should not be underestimated. Tracking in Bwindi usually takes place at around 1,400–2,000m above sea level, but in the Virungas the gorillas are often encountered closer to 3,000m – sufficient to knock the breath out of anybody who just flew in from low altitude. For this reason, travellers might want to leave gorilla tracking until they’ve been in the region for a week and are reasonably acclimatised – most of Uganda lies above 1,000m.

Trackers must meet (with passport or photocopy thereof to hand) at the relevant trailhead at 08.00 and will be given a short briefing about what to expect before they depart into the forest. It is no longer the case that permits specify which gorilla group you will track. At trailheads servicing more than one habituated group, however, the rangers usually do their best to allocate older or relatively unfit-looking trackers to whichever group they expect to be easiest to reach on the day, so if you need special consideration, best get there a bit early. Take advantage when the guides offer you a walking staff before the walk; this will be invaluable to help you keep your balance on steep hillsides. Once on the trail, don’t be afraid to ask to stop for a few minutes whenever you feel tired, or to ask the guides to create a makeshift walking stick from a branch. Drink plenty of water, and do carry some quick calories such as biscuits or chocolate. The good news is that in 99% of cases, whatever exhaustion you might feel on the way up will vanish with the adrenalin charge that follows the first sighting of a silverback gorilla!

In all reserves, ordinary trackers are permitted to spend no longer than 1 hour with the gorillas (people who sign on for the habituation experience can stay for up to 4 hours). Above all, do bear in mind that gorillas are still wild animals, despite the ‘gentle giant’ reputation that has superseded the old King Kong image. An adult gorilla is much stronger than a person and will act in accordance with its own social codes when provoked or surprised. Accidents are rare, but still it is important to listen to your guide at all times regarding the correct protocol in the presence of gorillas.

BINP is also one of the finest birding destinations in Uganda, thanks in part to the presence of 23 Albertine Rift Endemics, while other attractions include forest walks in search of smaller primates such as black-and-white colobus and L’Hoest’s monkey. There are also a few reputable cultural programmes that offer the opportunity to interact with the Batwa Pygmies who were evicted from the forest interior following the gazetting of the national park.

The original city centre – little more than a fort and a few mud houses – stood on the hill known today as Old Kampala © Ariadne Van Zandbergen, Africa Image Library

Kampala

Extending over a series of rolling hills and swampy valleys at the head of Lake Victoria’s Murchison Bay, Kampala, the economic and social hub of Uganda, is the archetypal African capital – more verdant than many of its counterparts, not quite so populous or chaotic as others – but essentially the familiar juxtaposition of a bustling compact high-rise city centre rising from a leafy suburban sprawl, increasingly organic in appearance as one reaches its rustic periphery.

As a city, Kampala’s history dates back to the arrival of Captain Frederick Lugard, who established his camp on the stumpy Kampala Hill in 1890. However, the more prominent of the surrounding hills had already been used by the Bugandan kabakas for their kibugas (citadels). Kasubi Hill, only 2.5km northwest of the modern city centre, served briefly as the capital of Kabaka Suuna II in the 1850s, and it also housed the palace of Kabaka Mutesa I from 1882–84, while Mengo Hill formed the capital of Mutesa’s successor Mwanga, as it has every subsequent kabaka. The name ‘Kampala’ derives from the Luganda expression ‘Kosozi Kampala’ – ‘Hill of Antelope’ – a reference to the domestic impala that cropped the lawns of Mengo during Mutesa’s reign.

In the first decade of the post-independence era, Kampala was widely regarded to be the showpiece of the East African community: a spacious garden city with a cosmopolitan atmosphere and bustling trade. It was also a cultural and educational centre of note, with Makerere University regarded as the academic heart of East Africa. Under Idi Amin, however, Kampala’s status started to deteriorate, especially after the Asian community was forced to leave Uganda. By 1986, when the civil war ended, Kampala was in complete chaos: skeletal buildings scarred with bullet holes dotted the city centre, shops and hotels were boarded up after widespread looting, and public services had ground to a halt, swamped by the huge influx of migrants from war-torn parts of the country.

Some 30 years later, Kampala is unrecognisable from the dire incarnation of the mid 1980s. The main shopping area along Kampala Road might be that of any African capital, while the edge of the city centre has seen the development of a clutch of bright, modern supermarkets and shopping malls. The area immediately north of Kampala Road, where foreign embassies and government departments rub shoulders with renovated tourist hotels, is as smart as any part of Nairobi or Dar es Salaam. Admittedly it’s a different story downhill of Kampala Road where overcrowded backstreets, congested with hooting matatus and swerving boda drivers, reveal a more representative face of Kampala – the city as most of its residents see it.

Kampala is not only smarter than it used to be but considerably larger. These days it covers over 200km², as the population has risen from 330,000 in 1969 to over 2.2 million inhabitants today, if one includes the peripheral sprawls of Nansana and Kira – a figure easily ten times greater than any other town in Uganda.

Kibale Forest

Uganda’s premier chimpanzee-tracking destination, Kibale National Park protects 766km² of predominantly forested habitat that extends more than 50km south from the main Fort Portal–Kampala Road to the northeast border of Queen Elizabeth National Park. Originally gazetted as a forest reserve in 1932, Kibale was upgraded to national park status, and extended southward to form a contiguous block with the Queen Elizabeth National Park, in 1993. The trailhead for chimp tracking and main centre of tourist activity within the park is the Kanyanchu Visitors’ Centre, which lies 35km south of Fort Portal along a newly surfaced road that continues south to Kamwenge and Ibanda. Chimps aside, Kanyanchu offers some superb forest birding and monkey viewing, with the community-run Bigodi Wetland Sanctuary, only 5km away immediately outside the park boundary, being a particular highlight in this respect.

Kibale National Park is dominated by rainforest, but this is interspersed with tracts of grassland and swamp. Spanning altitudes of 1,100– 1,590m, Kibale boasts a floral composition transitional to typical eastern Afromontane and western lowland forest with more than 200 tree species recorded in total. Unlike Budongo Forest to its north, Kibale wasn’t logged commercially until the 1950s, when it became an important source of timber for the Kilembe Copper Mine near Kasese, and logging was discontinued during the civil war. As a result, areas of mature forest are still liberally endowed with large-buttressed mahoganies, tall fruiting figs, and other hardwood trees whose canopy is up to 60m above the ground. It also supports a dense tangle of lianas and epiphytes, while the thick undergrowth includes wild Robusta coffee.

At least 60 mammal species are present in Kibale National Park. It is particularly rich in primates, with 13 species recorded, the highest for any Ugandan national park. Kibale Forest is the most important stronghold of Ugandan red colobus, but it supports eight other diurnal primate species: vervet, red-tailed, L’Hoest’s and blue monkeys; Uganda mangabey; black-and-white colobus; olive baboon; and chimpanzee. It also supports four species of nocturnal prosimian including the sloth-like potto.

Most prominent among Kibale’s primates is a chimpanzee population of up to 1,500 individuals, divided into at least a dozen different communities, four of which are habituated to humans. The Kanyantale Community has been the subject of daily tourist tracking excursions out of Kanyanchu since 1993. The other three are all reserved for researchers and include Ngogo, which is the world’s largest chimp community, numbering more than 200 individuals. Another community called Buraiga, whose territory lies close to Kanyanchu, is currently being habituated for tourism.

Although they are often seen in large herds, zebras actually form relatively small stable social groups © Ariadne Van Zandbergen, Africa Image Library

Kidepo Valley National Park

Lynchpin of the nascent northeastern safari circuit, Kidepo Valley (KVNP) is Uganda’s third-largest national park after Murchison Falls and Queen Elizabeth, and it vies with these two as Uganda’s most alluring safari destination. It has a remote location in the extreme northeast of Karamoja subregion, more than 500km from Kampala, bordering South Sudan to the northwest, and only 5km from the easterly border with Kenya.

Notable for its rugged mountain scenery and compelling wilderness atmosphere, KVNP also offers some exceptionally good game viewing, particularly in the Narus Valley with its dense populations of lion, buffalo, elephant and many smaller ungulates. Prior to 2011, the expense and difficulty of reaching the park meant it attracted a low volume of tourists, but this has changed in recent years as a result of increased stability in northern Uganda, greatly improved approach roads, and the opening of several lodges. Even so, KVNP retains a genuinely off-the-beaten-track character by comparison with most other comparably wildlife-rich savannah reserves in East Africa.

The original 1,259km² reserve was upgraded to national park status following independence in 1962, and extended to its present size of 1,442km² seven years later. Altitudes range from 914m above sea level to the 2,750m peak of Mount Morungole, the highest point on an extinct volcanic range running along the park’s southeastern border. The slightly taller Mount Lutoke (2,797m), which lies on the opposite side of a 50km border shared with South Sudan, is also visible from several points in the park. This ruggedly mountainous terrain is broken by the Narus Valley in the southwest and the Kidepo Valley in the northeast.

KVNP has a moister climate than other parts of Karamoja, but almost all the average annual rainfall of 800mm falls between April and October, so the plains become very hot and parched towards the end of the dry season. The park is named after the river Kidepo, a derivative of the Karamojong ‘akidep’ which means ‘to pick’, and refers to the fruits of the borassus palms that line this seasonal waterway and formed an important source of nourishment in past times of drought. The only perennial river is the Narus, which flows through the eponymous valley, and attracts a profusion of game in the dry season.

The dominant habitat in the Narus Valley is open grassland studded with tall sausage trees (Kigelia africana) and the massive elongated fruits for which they are named. The Kidepo Valley supports drier acacia woodland, though some significant stands of borassus palms line the watercourses. Elsewhere are patches of montane forest and riparian woodland. KVNP protects one of the most exciting faunas of any Ugandan national park, although its total of 86 mammal species has been reduced to 77 after a rash of local extinctions in recent years. The bird checklist of 470 species is second only to Queen Elizabeth National Park, and includes more than 60 birds recorded in no other Ugandan national park.

At Murchison Falls, the Nile explodes through a 6m-wide gorge to form the most dramatic feature along its 6,650km course © Ariadne Van Zandbergen, Africa Image Library

Murchison Falls

Flanking the 100km stretch of the Victoria Nile that arcs west from Karuma Bridge towards Lake Albert, the 3,840km² Murchison Falls National Park (MFNP) is the largest protected area in Uganda, and one of the most exciting. Its centrepiece Murchison Falls is the most electrifying sight of its type in East Africa, with the fast-flowing but wide Nile being transformed into an explosive froth of thunderous white water as it funnels through a narrow cleft in the Rift Valley Escarpment. MFNP offers some superb terrestrial and boat-based game viewing, with lion, elephant, hippo, buffalo and Rothschild’s giraffe being particularly common along the north bank of the Nile. The park is the largest component in the greater Murchison Falls Conservation Area (MFCA), which also incorporates the collectively managed 750km² Bugungu and 720km² Karuma wildlife reserves to its south.

From a visitor’s perspective, the most important feature of Bugungu and Karuma is the Kaniyo Pabidi Forest, which harbours a chimpanzee community that’s been habituated for tourists, as well as a number of localised forest birds. For most birders, however, the star attraction among the 550-plus species recorded in the MFCA is the shoebill, an elusive and bizarre waterbird frequently seen in the delta where the Nile empties into Lake Albert.

MFCA offers a diverse selection of activities to visitors. Most popular, and best undertaken in the afternoon with the sun in the west, is the atmospheric and all-but-obligatory return boat trip that follows the Nile from Paraa to the base of Murchison Falls. This is closely followed in the must-do stakes by a morning game drive on the Buligi Circuit, a network of game-viewing tracks traversing the 10km-wide peninsula that separates the Victoria and Albert Niles as they course in and out of Lake Albert. For those with more time and/or deeper wallets, other highlights include early morning hot-air balloon safaris out of Paraa, chimpanzee tracking or forest birding at Kaniyo Pabidi, the spectacular Top of the Falls Viewpoint and associated Honeymoon Track on the south side of the river, the boat trip downriver from Paraa to the bird-rich Lake Albert Delta, and the oft-neglected game-viewing road running northeast of Paraa towards Wankwar Gate.

Tackle the spectacular rapids on the Nile River near Jinja © Nile River Explorers

Nile rafting near Jinja

Rafting trips on the Nile are offered by four companies: Adrift, Nile River Explorers (NRE), Nalubale Rafting and White Nile Rafting. Rafting excursions can be booked directly with the rafting company, or indirectly through any tour company in Jinja or backpacker hostel in Kampala.

The rafting companies listed offer similar fullday itineraries starting on the West Bank of the river above the rapid known as Jaws and finishing near Kalagala Falls. This is a new route necessitated by the flooding associated with Isimbi Dam in 2018–19 but it still includes ten rapids including the Grade V Overtime and Bad Place and it also offers an opportunity to see a lot of different birds, and to swim in calm stretches of water. All companies charge US$145 for a full-day excursion inclusive of return transportation from Kampala or Jinja, buffet lunch, and beers and sodas. Half-day rafting trips are also available at a cost of US$125 per person.

Jewel-like Lake Kifuruka is just one of the 30-plus crater lakes that stud the Rwenzori footslopes near Fort Portal © Ariadne Van Zandbergen, Africa Image Library

Rwenzori Mountains

Gazetted in 1991, the 996km² Rwenzori Mountains National Park protects the upper slopes and glacial peaks of the immense 5,109m-high mountain range that runs along the Congolese border for a full 120km south of Lake Albert and north of Lake Edward. Rwenzori is Uganda’s most alluring hiking destination, traversed by two discrete six- to nine-day trail circuits, one starting at Kilembe in the south and the other at Nyakalengija about 20km further north. These trails pass through a fascinating succession of altitudinally defined vegetation zones, ranging from montane rainforest to Afro-alpine moorland, and the scenery can be breathtaking. Be warned, however, that the upper Rwenzori is widely regarded to present tougher hiking conditions than the ascents of mounts Kilimanjaro or Kenya, largely due to the mud, which can be knee-deep in places after rain, and as such it requires above-average fitness and stamina. Unlike on Kilimanjaro, normal Rwenzori hikes stick below the snowline (around 4,500m), which reduces the risk of altitude-related illness, but the glacial peaks are accessible to experienced technical climbers. At the other end of the commitment scale, those with limited time, money or stamina can choose from a number of day or short overnight hikes through the forested slopes above Kilembe or Nyakalengija, or head up to Fort Portal and follow the Northern Rwenzori mini-hike between nearby Kazingo and Bundibugyo.

Roughly 120km long and 65km wide, the range incorporates six main massifs, the tallest being Mount Stanley, whose loftiest peaks are Margherita (5,109m) and Alexandra (5,083m). Margherita is exceeded in altitude elsewhere in Africa only by the free-standing volcanic cones of Kilimanjaro and Kenya, meaning that the Rwenzori is the highest proper mountain range anywhere on the continent. There are four other glacial peaks – Speke (4,890m), Emin (4,791m), Gessi (4,715m) and Luigi di Savoia (4,627m) – but global climate change has caused the combined extent of glacial coverage to retreat from 7.5km² in 1906 to a mere 1.5km² today.

As is the case with other comparably lofty East African mountains, the vegetation of the Rwenzori can be divided into several altitude zones, each with its own distinct microclimate, flora and fauna. The Afro-montane forest zone, which starts at 1,800m, has the most varied fauna. Above 2,500m, closed canopy forest starts to give way to dense bamboo stands. Higher still, spanning altitudes of 3,000m to 4,500m, the open vegetation of the heather and alpine zones has an otherworldly quality, with forests of giant heather trees throughout, and the striking 10m-high Lobelia wollastonii and giant groundsel (Senecio admiralis) most common above 3,800m. The diverse fauna of the Rwenzori includes 70 mammal and 177 bird species, several of the latter being Albertine Rift Endemics. It is the only national park in Uganda where the Angola colobus has been recorded, though identification of this localised monkey will require careful examination as the similar and more widespread black-and-white colobus also occurs on the mountain. The only other mammal you’re likely to see in the forest is the blue monkey, but elephant, buffalo, golden cat, servaline genet, chimpanzee, yellow-backed duiker and giant forest hog are all present. At night, the forest resounds with the distinctive and eerie call of the southern tree hyrax. Mammals are scarce above the forest zone.

Semliki National Park

Gazetted in 1993, Semliki National Park – previously known as Bwamba Forest, a name that often crops up in old ornithological literature – protects a practically unspoilt 220km² tract of rainforest bounded to the northwest by the Semliki River as it runs along the Congolese border into Lake Albert, and to the southeast by the surfaced main road connecting Fort Portal to Bundibugyo. The tropical lowland forest of Semliki, set at an average altitude of 700m, forms an ecological continuum with the Ituri Forest, which extends eastward for more than 500km to the Congo River, and it supports a wealth of wildlife unknown from elsewhere in East Africa, including more than 35 bird species. Despite this, the relative remoteness of the park means it is seldom visited, even by ornithological tours.

Over 435 bird species have been recorded in Semliki National Park. The checklist includes a full 35 Guinea–Congo forest biome bird species unknown from elsewhere in East Africa. Furthermore, another 12 species with an extremely limited distribution in East Africa are reasonably likely to be seen by visitors spending a few days in Semliki National Park.

The entrance fee is US$35/25 for FNR/FR per 24 hours. No fee is charged for driving or walking along the main road to Bundibugyo, which falls just outside the park’s southeastern boundary, or for staying overnight at Bumaga Visitor Camp. As of January 2019, no additional charge is made for the short walk to Sempaya Hot Springs. Other activities such as birding walks attract a guide fee of US$30 per person over and above the entrance fee. Because Semliki National Park and Toro-Semliki Wildlife Reserve are separate entities, you need to pay two sets of entrance fees if you visit both, even if it falls within the same 24-hour period.

Sipi Falls

Elgon’s main tourist focus is the small trading centre of Sipi, which lies at an altitude of 1,775m on the mountain’s northeastern footslopes, only 45km from Mbale along a good surfaced road. The village overlooks the 99m-high Sipi Falls, the last in a series of three pretty waterfalls formed by the Sipi River as it cascades downhill from the upper slopes of Mount Elgon into the Kyoga Basin. Serviced by half-a-dozen resorts and lodges that collectively cater to most tastes and budgets, Sipi is a very peaceful and pretty spot, and it makes a most agreeable base for gentle day walks in the surrounding hills, which offer spectacular views to the lowlands further west and – weather permitting – occasional glimpses of the Elgon peaks.

The most popular walking trail, only 20 minutes each way, leads from behind the post office in Sipi trading centre to the base of the main waterfall. If you choose, you can continue for another 20 to 30 minutes to reach a cluster of caves on the cliff above the river. The largest cave extends for about 125m into the rock face, and contains rich mineral salt deposits that have clearly been worked extensively at sometime in the past, as well as traces of petrified wood. Walking back to the trading centre along the main road, you’ll pass the top of the main waterfall, as well as Sipi Mise Cave, an important local shrine set within a small forest-fringed cavern.

It is more-or-less mandatory to take a guide on walks to the waterfalls, other local hikes and coffee tours. This not only helps you locate some of the sites, but also the guiding fees include a contribution to local landowners for access to the falls.The going rate is around US$7–10 per person depending on the duration of the walk and where you arrange it.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Uganda:

Related articles

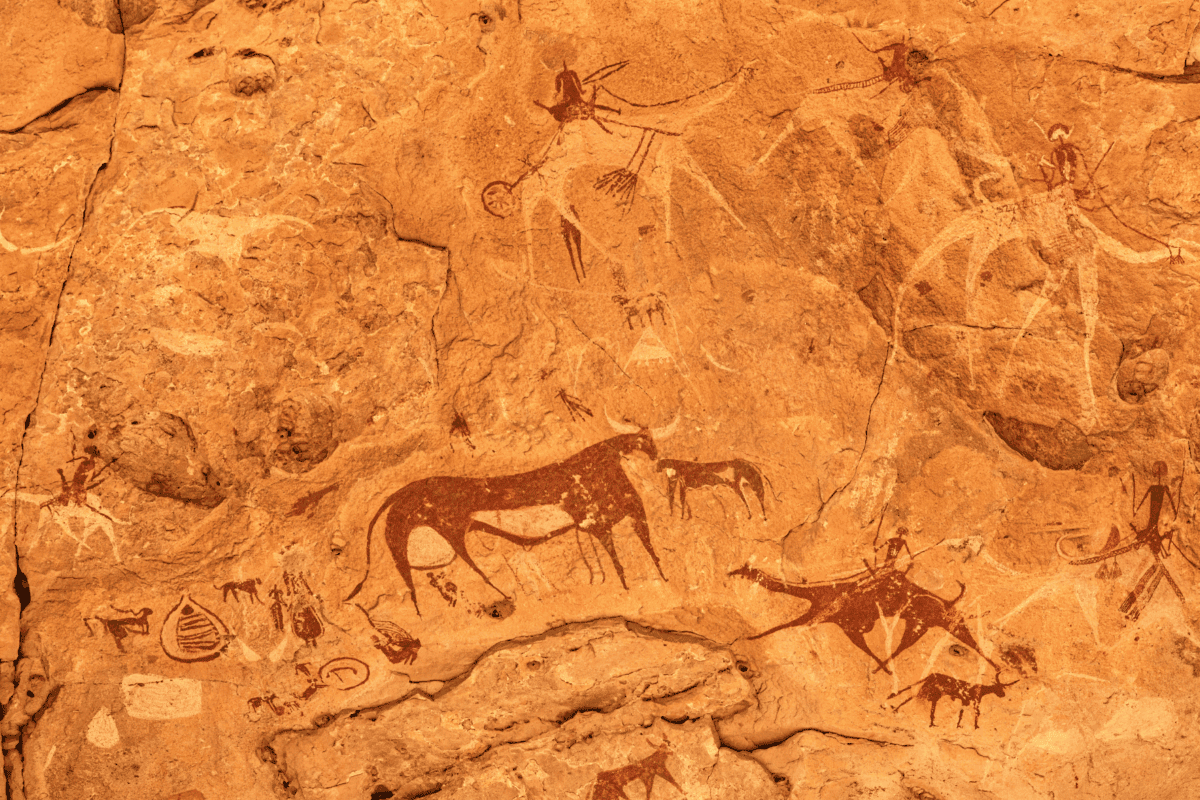

Africa has some magnificent centuries-old rock art – how many have you visited?

From boiling lakes to vast alpine bodies of water, these are our favourite lakes from around the world.

Our pick of the best national parks to visit in Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda.

We’ve scoured the African continent for some of the best sites to get up close and personal with lions.

Covering even more of the world than our guidebooks, forests are ubiquitous but almost always different.

The story of the shoebill, one of Africa’s most elusive birds.

Whether you are a novice or an avid birdwatcher, aviary spectacles can be amongst the greatest in the animal kingdom.