Inhabited by over 200 indigenous tribes, and large populations of Chinese and Malay people, Borneo’s fascinating ethnic mix is as colourful as the weavings in the tribal handicrafts and dress.

Tamara Thiessen, author of Borneo: the Bradt Guide

Tropical jungles, remote rivers, orangutans, hornbills and headhunting history… The Southeast Asian island of Borneo is a magnet for those seeking off-the-beaten path adventure, rare natural wonders and exotic tribal cultures. Straddling the equator between the South China, Celebes and Java seas, the remote island is three times the size of the UK and the third-biggest island in the world after Greenland and New Guinea.

Shaped by a history of seafaring migrations, tribal cultures and European colonialism, the Malaysian states of Sarawak and Sabah, and the Sultanate of Brunei are all found in northern Borneo. Recognised as a global biodiversity hotspot on a par with the Amazon and equatorial Africa, Borneo accounts for less than 1% of the earth’s surface, but over half of all existing plant and animal species.

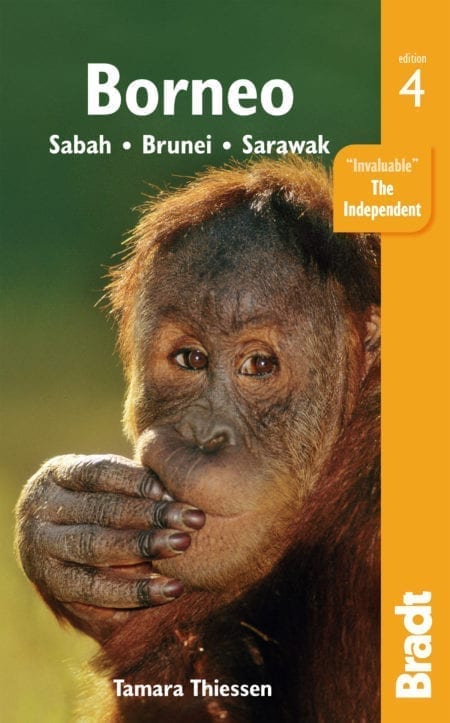

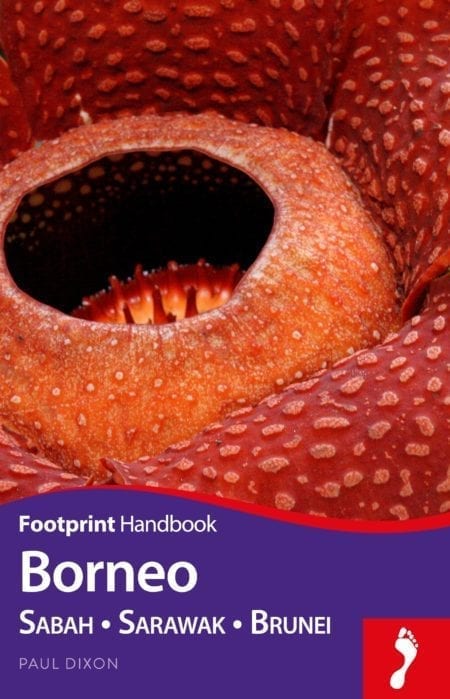

Many of those thrive in the diverse, rich, lowland tropical rainforests, home to Asia’s largest primate the orangutan, the Sumatran rhinoceros, the Bornean pygmy elephant and thousands of unique flowering plant species.

Inhabited by over 200 indigenous tribes, and large populations of Chinese and Malay people, Borneo’s fascinating ethnic mix is as colourful as the weavings in the tribal handicrafts and dress. To top it all off, each culture has mouth-watering food specialities – from Chinese rice and noodle dishes, to spicy Malay cuisine and rainbow arrays of fruit.

The jewel in the crown of the island’s mountainous interior is Mount Kinabalu. The tallest peak between the Himalayas and Papua New Guinea rises up to 4,095m altitude at the heart of Gunung Kinabalu National Park. The world-heritage listed reserve is a nature-lover’s wonderland of thousands of bird and plant species.

For more information, check out our guide to Malaysia (Borneo)

Food and drink in Malaysia (Borneo)

Borneo’s mix of cultures creates a piquant culinary bouillabaisse. We hope this section will help you avoid the many tongue-tied moments many have experienced trying to order food, with no certainty of what they’re about to eat!

Malaysians and Bruneians are nations of passionate eaters. While the two countries have distinct food, they also share many common Malay and (to a lesser extent in Brunei) Chinese dishes. Rice (nasi) and noodles (mee) are staples of Malay and Chinese cuisine – if you don’t like either, be prepared to starve! The Chinese and Malay populations rely heavily on noodles in laksa and other soups, as well as main-meal dishes. Freshly made mee comes in various forms: large white or yellow ribbon wheat noodles, spaghetti thin noodles and clear vermicelli noodles. In coffee shops you can often choose your noodles from the masses hanging at a counter at the entrance. Then you have to decide on the style you want them cooked – the big differences being ‘wet’ (with sauce) or ‘dry’ (without); fried (goreng) or not fried; spicy or mild. Dried noodles are increasingly being used, so when you get the chance to taste the real thing then do so. Sedap dimakan! (Bon appetit!)

Travel and visas in Malaysia (Borneo)

Visas

If you have already passed through Malaysian customs in Kuala Lumpur, it is surprising to face passport control again on arrival in Sabah or Sarawak, but keeping control of their own immigration checks was one of the conditions for them joining the Federation of Malaysia in 1963. It’s all just a formality, particularly for citizens of the UK, Australia, Ireland, the USA, Brazil, Canada, France, Italy, Germany, the UAE, South Korea, Japan, South Africa, Tunisia and a host of other western European, South American and Middle Eastern countries who do not need a visa to enter Malaysia for a visit of up to three months. It is mandatory, however, to be holding a passport valid for at least six months on arrival, as well as a return or onward ticket. An extension of up to two months is possible. Passport holders from countries which require a visa will be issued with a 30-day stay on arrival, which can in principle be extended for another 60 days at the Immigration Department in Kota Kinabalu. Citizens of countries including Costa Rica, Mexico, Lithuania and Ukraine require a visa for a stay exceeding one month.

Getting there and away

The main international airports in Malaysian Borneo are Sabah’s capital Kota Kinabalu – ‘KK’ for those in the know – and Kuching, the capital of Sarawak, which is less easily shortened. Clearly your choice of airline will be determined by your proposed itinerary. Sabah Tourism provides a summary and map of all international flights to Kota Kinabalu under its ‘Getting to Sabah’ section.

Getting around

By air

Though distances within each Bornean state are not particularly long, most people rely on air travel, not just for longer journeys, such as west-to-east-coast passages, but also between regional cities which are connected within two–three hours, such as those along the Pan-Borneo Highway. This is largely due to the abundance of cheap flights. Why spend six hours travelling by car when you can fly in 40 minutes? On top of that, there’s the deterrent state of many roads. Low-cost airlines have popularised air travel in Borneo, as they have done throughout Asia. City-to-city and regional hops such as Kota Kinabalu to Tawau or Sandakan, are easier than climbing on a bus for a six–eight-hour journey. Likewise for metropolises on Sarawak’s 1,000km coastline – several daily flights link up Kuching, Sibu, Bintulu and Miri in under an hour. If speed and convenience are what you are looking for, then flying is a good option. If you are concerned about the environmental effects of air travel, or want to take in the scenery between towns (and brave the roads), then read on for other options.

By car

The cost of car rental is similar to Western prices: around RM100–150 a day. Car journeys are particularly economical in Brunei, where petrol costs 53 cents a litre, so about B$20 to fill a tank. (Foreign-registered vehicles pay almost double that.) In Sabah and Sarawak, unleaded fuel costs around RM2.30 a litre (RM105 a tank). Petrol is the great exception – just about everything else is double the price in Brunei! Most national driving licences (UK, US, Australian) can be used in Malaysia for three months, beyond which you require either a Malaysian driving licence or an annually renewable International Driving Permit.

By bus

While buses provide a cheap, comfortable and potentially efficient form of transport, the urban bus system in both Sabah and Sarawak has historically been a bit of a shambles. Prevalent problems have been a maze of different bus companies, sometimes serving the same areas, a lack of a central bus terminal, and confusion over where to catch particular buses, at least for the uninitiated. The situation is improving in the capitals as infrastructure evolves. In smaller towns, buses may not be the best option, though I always find a bus journey – no matter how challenging (and perhaps even more so for that) – an incredible window on local culture and people. When the fascination factor wears off a little, or you are just too tired, taxis can be a cheap alternative for small distances. Indeed Malaysia is one of the rare places in the world where I feel I can genuinely afford them.

By boat

Ferries are an efficient and interesting way of travelling in Borneo. Some of the main links are Brunei to Sabah (via Labuan Island), Brunei to Limbang in Sarawak, Kota Kinabalu to Brunei (via Labuan), and Labuan to Menumbok in Sabah. Various operators, including passenger and car ferries, ply these routes. Labuan Tourism is a good place to check timetables and prices. Labuan is a mandatory thoroughfare of ferry passage between Sabah and Brunei. There are no direct passages.

Health and safety in Malaysia (Borneo)

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on istm.org. For other journey preparation information, consult travelhealthpro.org.uk (UK) or wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ (US). Information about various medications may be found on netdoctor.co.uk/travel. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Tropical diseases

Malaria

This is a serious and potentially fatal disease transmitted by mosquitoes, for which there is no vaccine. There are hugely differing estimates of the prevalence of malaria in Borneo, ranging from ‘successfully eliminated’ to ‘widespread’. Most sources agree that the risk is greater in more remote areas and fairly low in urban and coastal regions. Current recommendations for prophylaxis are Malarone, doxycycline or Lariam for those travelling to rural areas of Borneo; unless none of these tablets are suitable for you, then you would be advised to take them.

Seek medical advice as to which is the most appropriate for you and follow the regime recommended carefully. That said, no malaria tablets are 100% effective and so you should always take precautions against mosquito bites. This includes wearing trousers and long-sleeved shirts particularly between dusk and dawn. Apply insect repellents containing around 50–55% DEET to exposed skin at the recommended intervals, and when necessary sleep under a permethrin-impregnated bed net. These may not be provided, so it is wise to take your own, especially if you are visiting remote areas.

Early diagnosis of malaria is essential for effective treatment, so if you suspect you or a companion has contracted the disease then seek medical help as soon as possible. Symptoms are flu-like and may include fevers, chills, muscle and joint aches, headache, tiredness, nausea, vomiting, and occasionally diarrhoea. The only consistent feature is a high temperature of 38°C or more and that alone should also make you suspect malaria. It can develop from as early as six to seven days after exposure, to up to as much as one year, so continue to be vigilant upon your return and seek medical advice if you develop flu-like symptoms.

For further advice and malaria information, see fitfortravel.nhs.uk/destinations/asia-east/malaysia, nhs.uk/conditions/malaria/prevention, and traveldoctor.co.uk/malaria.htm.

Other diseases

There are periodic outbreaks of dengue fever with peak transmission from June to November (for which there is no vaccination). This viral infection is spread by day-biting mosquitoes. It causes a feverish illness with headache and muscle pains like a bad, prolonged, attack of influenza. There may be a rash. Recurrent infections can be more serious so it is important to try and avoid the disease in the first place by using DEET containing insect repellents during the daytime as well as in the evening.

Japanese encephalitis is another viral disease transmitted by infected mosquitoes. Vaccination is recommended for those likely to be frequently exposed to bites during long stays, repeated visits or if staying in rural infected areas. The newer vaccine Ixiaro (two doses given ideally 28 days apart; if time is short then the second dose may be given no less than 24 days aft er the first dose of vaccine) has none of the more serious side eff ects of the older vaccines and therefore should be recommended for all rural travel if time and budget allow.

This vaccine can be used in those aged two years and over. The disease is endemic, with small numbers of cases occurring year-round in East Malaysia (Sabah and Sarawak), but in addition epidemics occur following the start of the rainy season in Peninsular Malaysia (April to October) when mosquitoes are most active.

Safety

British, US and Australian authorities periodically issue warnings against travelling around the coast of East Malaysia, particularly the Celebes/Sulawesi Sea islands off the southeast coast of Sabah. Those warnings have again come to a head after a dire couple of years for the region in 2013–14. Over a decade after the kidnappings in 2000, which saw all Sidapan Island resorts closed, and a bolstered and continuing Malaysian military surveillance in the area, there has been a recent spate of kidnappings by Filipino bandits, even the murder of one tourist.

Furthermore, the regional political volatility and territorial disputes between Indonesia and Malaysia erupted in 2013 with the ‘invasion’ of Lahad Datu in Sabah by a group of armed Sulu rebels. I personally am nervous about dipping myself into the diving region right now, until things seem more under control. At the time of writing in 2015, the FCO were advising against all but essential travel to all islands off the coast of eastern Sabah between Kudat and Tawau, including Lankayan, Mabul, Pom Pom, Kapalai, Litigan, Sipadan and Mataking. Check the FCO website for the current advice before booking your trip.

Female travellers

After many years as a solo woman globetrotter, Malaysia probably stands out as the safest country in which I have travelled. Personal security, general public friendliness and political stability are all at a high. In September 2010, the Oxford Business Group identified the high levels of overall safety in Malaysia as one of the main reasons for it having ‘strengthened its position as Southeast Asia’s top tourism destination’.

In Asia as a whole, Malaysia rated second only to China for its political and social stability. With the exception of one very high-profile murder case, the murder of a former prime minister’s lover, no horrendous crimes against women immediately come to mind.

The sense of general personal security as a woman traveller is even greater in Borneo, because of the island’s friendliness and its relatively small cities. In my frequent and lengthy travels in Brunei, Sabah and Sarawak, I have never once felt threatened by men; irritated occasionally by slightly juvenile attitudes to women in Malaysia, but not spooked. In the main cities – Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Miri – I always feel safe walking around in key public areas, though poorly lit backstreets and more remote urban zones are best avoided at night. The fact that Malaysia is such a street-living society, with a density of people in public areas, boosts the overall feeling of safety.

In Brunei, the huge esteem shown for women makes it one of the safest countries in the world for female travellers. The incidence of crime is virtually nil – partly due to the penalties faced – and assaults against women are unheard of (though possibly go unreported).

The respect shown to me, and my own personal feeling of comfort, is no doubt heightened by my respect for Muslim customs and appropriate dress (longer skirts, blouses, no miniskirts or bare shoulders).

Muslim women in Brunei and Malaysia wear a tudong, a veil or scarf, on their head. While there is no expectation for foreigners to do the same, it is advisable to carry a light scarf in your bag to don at appropriate moments, such as visiting religious sites. While skimpier garments have become the norm amongst the clubbing classes of Kuala Lumpur, Borneo – particularly Brunei – is more conservative.

Travelling with a disability

A couple of major UK and US associations who deal with disabled travel have told me Borneo falls outside their radar. This is surprising and likely to change as tourist numbers increase. For the time being, travel on public transport, especially small town buses, would not be easy. Most four and five-star hotels claim to have facilities for the disabled including wheelchair access and ‘adapted’ rooms. The same can increasingly be said for independent hotels. The lack of dedicated disabled-friendly tours doesn’t mean there is a lack of tour companies ready to create an itinerary, or hook in with local companies who have the right staff and vehicles. Use the various associations as your advocates so that they know there is a demand for such information. Also visit the websites of Mobility International USA (miusa.org) and disabledtravelers.com.

LGBTQ+ travellers

One of the most highly regarded gay and lesbian associations active in Borneo is Utopia Asia (utopia-asia.com). Its general advice for travellers in Malaysia is: ‘Gay life in Malaysia as in other Asian countries is blossoming, despite conservative religion-based discrimination and outdated colonial era laws.’

Former deputy prime minister, Anwar Ibrahim, was famously ousted from office by a trumped-up sodomy conviction, overturned by Malaysia’s High Court in 2004. The case is still making waves, as issues of homosexuality and discrimination are slowly (very slowly) brought out of the conservative closet. Islam is enshrined as the official state religion in the Malaysian constitution. Muslims, local and visitors, are thus subject to religious laws that penalise gay or lesbian sexual activity with flogging, and male transvestism with imprisonment, though this is rarely the case.

The law does not in principle apply to non-Muslims. Yet homosexual citizens of any creed still face official discrimination. Police can arrest any person, Muslim or not, for having sex in a public place, such as cruise spots. That said, police rarely detain foreigners during raids on local gay businesses, focusing instead on ethnic Malay customers, almost 100% of whom by law are considered Muslim at birth. Still, visitors should respect Malaysian law and customs while guests in the country, as is the general rule of thumb for all travel.

See Utopia Asia’s Utopia Guide to Malaysia, which has listings for the gay and lesbian scene in 17 cities including Kota Kinabalu and Kuching. The guide, which can be ordered online (utopia-asia.com), includes gay-scene city maps and listings of organisations, bars, discos, spas, accommodation and restaurants, with a special section highlighting venues that are particularly welcoming to women.

Kota Kinabalu is definitely Borneo’s capital of camp. While there are no flagrantly gay hotels, some are discreetly so, while others are gay-friendly. There are also some well-known gay and lesbian bars and nightclubs in town. Kuching is more conservative; while Brunei takes the issue to a whole new level, or planet, of ethics.

Overt tolerance of homosexuality is non-existent, and the gay community exists mostly ‘undercover’. The result is a weekend exodus of Brunei’s closet gays to the nearest place where they can show public displays of affection without the fear of being arrested – generally Miri in Sarawak. The former oil city has inadvertently developed a great future in gay tourism.

Families

Overall, Malaysian Borneo is safe, sunny and friendly and makes an inexpensive, educational, adventurous and exotic family holiday.

Far from just a sun-seeker’s destination, it offers enriching opportunities such as volunteer family holidays, living and helping out in one of the villages, or working with wildlife.

Many city hostels – especially the ‘lodge’ kind – have family rooms from RM115 with breakfast included. With lounges, sun decks and other travellers for company, these often provide a more fun and instructive atmosphere than the cramped, sequestered environment of shoestring hotels, which offer family rooms from RM100 to RM150.

If you have more to spend, and want more privacy and comfort, most mid-range to luxury hotels have family rooms or self-contained suites with separate living spaces and multi-bedrooms and bathrooms. Another good option is serviced apartments. Beyond the cities, beach resorts have larger rooms, or self-contained accommodation; or pay for several rooms to accommodate your brood. Mountain resorts often have self-contained chalet accommodation with equipped kitchens. Other options in rural areas are longhouse rentals and family-friendly homestays.

Single travellers

Many pros and cons of travelling solo in Borneo are common to all destinations. Particularly in luxury hotels, employees frequently grill me as to whether it is ‘just one for breakfast?’ ‘I’m not hiding anyone’ is my usual reply. A book or newspaper is a great refuge from indiscreet stares.

Financially, single travellers are heavily penalised with the lack of single-room rates: the difference in price between a single and double is either non-existent or negligible. Choose instead to stay in places where being single does pay – homestays, bed and breakfasts, hostels, budget or mid-range beach resorts, and the occasional hotel suite or apartment which offer rates suitably priced for the ‘flash packer’.

Even if you have the money for a more expensive hotel room, independently run or smaller-size accommodations can be more convivial, if it’s company you are after. And many offer the possibility of upgrading to a bigger, more comfortable room. If you prefer a hotel environment, you can always go for the premium rooms or suites of budget city hotels, or serviced apartments. The same price bracket in some country hotels may get you anything from a superior room to a suite.

When to visit Malaysia (Borneo)

Climate

Borneo’s climate is equatorial-tropical, distinguished by marked wet and dry seasons: the wet season (or ‘northeast monsoon’) generally runs from November to March, the dry season (or ‘southwest monsoon’) from May to October. There is no official start and end point between seasons. In the wet season, there are usually daily rains, and sometimes violent storms, monsoon winds, flooding, landslides and torrential rains.

Half of the annual rainfall on Sarawak’s west coast falls between December and March, while the hilly slopes of Sarawak’s inland Kelabit Highlands receive the highest annual rainfall of the state – more than 5,000mm. The wettest months tend to be January and February, followed directly by the driest – March and April. In more equatorial Sarawak, there is little variation in day length throughout the year – with only a seven-minute difference between the shortest and longest days.

Weather

Wet or dry season? There is no clear-cut best time to visit Borneo insofar as sunshine and warm weather are concerned (this is the tropics after all), but depending on the nature of your holiday, seasons may count considerably. Each has its advantages and drawbacks. The dry season (southwest monsoon) generally occurs from May to October, though huge downpours and floods can occur during that time, particularly in June and July. The wet season (northeast monsoon) reigns from November to April, and while monsoon rains may prove challenging, they are also atmospheric and can quickly clear to blue skies. As is the case for the entire planet, climate change is sparking increasing seasonal unpredictability.

For active and adventure holidays, the wet season is most likely to hinder your travel plans. Heavy rains and general bad weather may see flights to remote regions cancelled and likewise, disrupt boat travel. Trekkers should be prepared for short bursts of wet weather at any time of the year. During the northeast monsoon, open seas can be extremely rough; in January 2007, a tour company boat capsized off the north coast of Sabah due to a sudden change in weather conditions. On the other hand, low rainfall and river levels often affect boat travel. In hotter periods, upriver trips end up being partly self-propelled, with travellers required to hop out of longboats and help push them upstream.

Crowds

If crowds bother you, best avoid school holidays and major festive celebrations. Not only can it be hard to find accommodation during these busy periods, but hotels can be very noisy. The main school holidays usually fall between the last week of May and last week of June, and six weeks from mid-November through to the end of December. There are also weeklong holidays around mid- March and late August.

What to see and do in Malaysia (Borneo)

Bako National Park

Sarawak’s oldest national park and Malaysia’s second oldest, Bako National Park (Taman Bako) was established in 1957. Covering 27km² at the end of the Muara Tebas Peninsula, adjacent to Santubong, the park has a spellbinding quality – no doubt due to its astounding diversity of landscapes. Bako has 25 distinct kinds of plant life and seven ecosystems. From Tanjung (Cape) Rhu to Tanjung Po, and all the beaches and bays in between, it sweeps through mangrove, heath, peat swamp and mixed dipterocarp forest, grasslands, sandstone cliff s and sea-eroded coastal formations. With a population of some 280 proboscis monkeys, the chances of sightings as you wander along the many well-marked trails are high, particularly early morning or towards dusk. Big-headed, bristly snouted pigs often wander right in front of the park HQ, scavenging for scrap food or wallowing in mangrove mud. The animals to be most wary of are the audacious macaque monkeys – known to raid many an unlocked room, as well as the canteen and dustbins, and even confront guests for food they might be carrying. ‘Compulsive thieves’ is how they are not-so-fondly described!

Wildlife

Bako is often tipped as the best park in Sarawak for wildlife experiences. Apart from the monkeys, there are otters, crabs, frogs and lots of lizards and snakes – lime-green whip snakes, green spotted paradise snakes, and Borneo’s only dangerous snake, the triangular-headed pit viper. The wildlife experience starts among the mangroves of Telok Assam, park HQ area, where many of the 150 locally listed birds can be sighted.

Treks

Bako boasts one of Borneo’s best networks of park trails – 16 well-signed walks from hour-long forest strolls (1.6km return) to full-day treks (21km return). Pick up a map and flora-and-fauna guide at the park HQ, where you must also register for longer forest forays. You may find one or more of the trails closed for maintenance. It’s amazing how many kinds of vegetation you will pass in an hour as you climb up a couple of cliffs, and circumnavigate the inland of a bay. Both of the supposedly best trails for seeing the proboscis monkey – Telok Delima and Telok Paku – are about 2km return from Telok Assam (park HQ), with sightings also frequent in the mangroves near the park HQ. Pitcher plants are found along the red-arrowed Lintang Loop Trail (10.8km return).

Beach, bay and boat

Telok Pandan Kecil, reached via the 2.5km yellow-arrowed trail, is one of the nicest beaches, nestled within a secluded bay and rocky headland. To cut the journey, or to visit bays and coves further afield, you can charter a boat at park HQ and organise a pickup time with a boatman for a return journey. On the way, you will get to see the casuarina-topped limestone and sandstone cliffs and some of the coast’s fascinating eroded rock features like the Sea Stack.

Danum Valley

It is a bitter irony that one of the greatest ‘protected areas’ of Sabah, the Danum Valley Conservation Area (DVCA), exists alongside some of the most severe overlogging. The 438km² reserve is promoted as ‘the largest remaining area of undisturbed virgin lowland rainforest in Malaysia’, which has been set aside for research and education. However, as you drive into the ‘untouched’ area you will undoubtedly come across well-laden log trucks on the road, which can be upsetting. As Sabah Tourism declare candidly ‘a vast timber concession area borders all around Danum Valley’.

The road into the reserve passes through logged and regenerating forest areas – the DVCA is touched on every side by 3–100km of commercial forest, and beyond are oil palm plantations. Guides here express their heartbreak at what is happening, and what has already happened. Together with the Maliau Basin, Danum Valley is part of the huge 10,000km² timber concession of Yayasan Sabah (the Sabah Foundation). Since the 1980s, it has been a Class 1 Protected Forest Reserve and part of the foundation’s long-term Forest Management Plan, to remain unlogged for the purpose of wildlife conservation, education and research.

Gunung Kinabalu National Park

Mount Kinabalu was sacred to local indigenous communities long before Gunung Kinabalu National Park gained World Heritage UNESCO status in 2000. For the Kadazandusun the mountain is the resting place of their ancestral souls, so indigenous climbers have always made an offering to avoid being cursed. Lower zones of Gunung Kinabalu National Park are scarred by forestry, mining and slash-and-burn agriculture. The UNESCO listing did not come too soon – and some would argue, not soon enough.

Spread over 754km², an area larger than Singapore, the park encompasses several distinct mountain environments and climate zones. The coolest place in Borneo, it is a botanical and ornithological paradise, with over 300 bird species, 5,000 flowering plants and a multitude of mosses, ferns and fungi. The floral inventory includes 26 rhododendrons, nine pitcher plants, over 80 fig tree species and more than 60 species of oak and chestnut tree. The 1,200 orchid species range in size from being as small as a pinhead to having 2m-long stems.

Ascending from 600m to 4,095m above sea level, Gunung Kinabalu passes through 12 climate zones. Such variety bears a wealth of biodiversity, and flora and fauna adapted to the altering conditions, from conifers and lowland rainforest to alpine meadows. The massif comprises 16 granite peaks of various heights, culminating in the 4,095m summit. It was baptised Low’s Peak, after Sir Hugh Low, who led the first official expedition to the summit on 7 March 1851, when he was colonial secretary of Labuan.

At Panar Laban hut – 6km up the 8.5km trail – Low and his local guides performed the ritual sacrifice of a chicken to appease the ancestral spirits and seek safe passage. Two expeditions to explore the mountain’s flora and fauna led by Professor John Corner on behalf of the Royal Society of London in 1961 and 1964 were also important steps to the creation of the national park in 1964. According to the UNESCO World Heritage Centre, a World War II prisoner of war also played an instrumental role. One of six survivors of the Sandakan to Ranau death march, he formed the Kinabalu Memorial Committee hoping to ‘preserve the Kinabalu area for the decency of man and a facility for the enjoyment of all of Sabah’.

The pride of Sabah, the park gets about 400,000 visitors a year. Most do not climb to Gunung Kinabalu’s summit, preferring to soak up the sublime surroundings on the mountain’s lower slopes. Many hopes are being pinned on tourism as a sustainable job creator, reducing the reliance on agriculture. In June 2015, a 5.9 magnitude earthquake hit Mount Kinabalu, killing at least 16 people including a group of schoolchildren climbers from Singapore. The natural disaster shook locals deeply. Officials blamed the quake on a group of foreign tourists, who allegedly desecrated the mountains’ spirits by posing naked on the summit a few weeks earlier, and then posted their insensitivity on Facebook for all the world to see.

Gunung Mulu National Park

Approaching the Malaysian–Indonesian border, the deep northern Sarawak interior is an isolated area of rivers and mountains. Encircled by pinnacles and peaks, the World Heritage Site of Gunung Mulu National Park lies in a corridor of lowland rainforest criss-crossed by rivers and streams.

The 53,000ha park contains the largest limestone cave system in the world, formed from thousands of years of erosion. Since the beginning of a National Geographic expedition in 1977, over 300km of caves have been surveyed, though it is believed there could be at least twice as many more. Only four of the 25 caves and passages discovered are open to the public.

The park’s 17 different habitats enclose primary lowland rainforest, limestone forest, alluvial forest, tropical heath forest, peat swamp and riparian forest. Between altitudes of 35m and 2,375m, it contains a staggering 3,500 plant species, 4,000 types of fungi, 80 mammals, 270 birds, 130 reptiles and amphibians, 50 fish types and 2,000 different bugs, beetles and butterflies. Like Gunung Kinabalu National Park, it’s an entomologist’s dream, with hundreds of distinctive insect species including stick insects (Phasmids), camouflaged crawlies and butterflies (including Trogonoptera brookiana – Brooke’s birdwing butterfly).

Indigenous people were the first naturalists of the region. Penan and Berawan people lived in the area for centuries, hunting and gathering.

The park is bounded by three mountains – its namesake Gunung Mulu, Gunung Api and Gunung Benarat. In the 1920s, a Berawan rhino hunter, Tama Nilong, discovered the southwest ridge of Gunung Mulu, opening the way for its successful ascent. Nilong led South-Pole explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton and an Oxford University expedition to the summit in 1932. The National Geographic Society subsequently lobbied for the creation of a national park in 1976, and the 544km² area opened to visitors in 1985. Listed as a World Heritage Site in December 2000, this is one UNESCO natural treasure where the negative effects are on show just as much as the positive ones. Threats to the environment other than logging include pollution from locals, tourist hordes, and slack tour companies.

Caves

All caves are reached along solid timber-plank walks, and are visited by way of eco-lit cement paths. The 3km duckboard walk to reach Deer Cave and neighbouring Lang’s Cave is a lovely experience in itself, passing rainforest, peat swamp, alluvial flats, streams and some spectacular limestone outcrops. Two hour return treks led by park guides leave daily. Clearwater Cave and Cave of the Winds are reached from park HQ by longboat along the Melinau River in about 15 minutes (RM27 pp return), or via the 4km Moonmilk Walk that hugs the riverbanks much of the way. The most impressive site for stalactites and other formations is Lang’s Cave; the most amazing overall for its size and cavernous pit is Deer Cave (Gua Rusa). At a staggering 2km in length, this is the largest cave passage in the world – its main chamber has enough room for five St Paul’s Cathedrals!

Caving

Speak with the park HQ or a tour organiser about adventure caving at Mulu. A park brochure outlines eight cave escapades from beginner to advanced level, lasting from 45 minutes to ten hours. Some popular caves have been fitted with fixed ropes on the short descents and traverses, but you are advised to bring your own equipment for anything beyond that. The Sarawak Chamber – on the way to Gunung Api – is compared to an aircraft hanger that could house 40 Boeing 747s. The day trip starts at 07.30, tracing the Summit Trail for about three hours.

Trekking

Without a doubt, trekking away from the park’s HQ and hotels is the best way to feel the wonder of nature and get up close with the wildlife. There are many treks in the park: some require a guide, others can be done independently. Inform park officers before you do an unguided walk, as they are aware of weather conditions, including dangerously high water levels. Unguided treks include the four-hour Paku Waterfall through rainforest to a good swimming spot and the three-hour Long Lansat River Walk (RM180 for the longboat return transfer; 3 people minimum). The day walk to ‘Camp 1’ (guided) follows part of the Mulu Summit Trail and concludes at one of the camps used during the 1977 Royal Geographical Society expedition. The summit (guided) trek to the top of solitarystanding Gunung Mulu (2,376m) – Sarawak’s second-highest peak – is a 24km climb, conducted over two to three nights, lodging in forest huts with basic cooking facilities (park guide costs are RM1,000 for 1–5 people). En route to Gunung Api (1,750m) the Pinnacles is a 50m-high series of razor-shaped limestone outcrops, pointing skyward and interlinked with several caves. This tough, guided climb requires at least one overnight stay at Melinau Camp (‘Camp 5’). Most people stay two nights, depending largely on fitness levels. The first day’s trekking takes in visits to a couple of Mulu’s caves. Lodgings consist of sleeping mats in five open rooms, a self-catering kitchen (cooking equipment and utensils provided), and a dining room. You have to carry all of your own food, a sleeping bag and appropriate clothing. It costs RM250–800, depending on numbers. Accommodation costs RM22 per person per night; park guide RM400 for one to five people; longboat return RM370 for a group of one to four.

The popular tour-operated Headhunters’ Trail combines 15km of deep jungle trekking over two days with longboat journeys and an optional longhouse stay. The route taken is that of Kayan headhunting parties who paddled up the Melinau River to Melinau Gorge before launching raids against the people of the Limbang area. This trip can also be done from Limbang to Mulu Park HQ. Another option is to add a night and include the Pinnacles climb (from Camp 5) in the trip.

Longboat safaris

A couple of trips visit Penan settlements along the Sungai Tutoh and Sungai Melinau rivers. These are very prescriptive though, so if you prefer to explore more independently then take your own day trip on the rivers.

Maliau Basin

A ‘protected forest reserve’ once open to logging, Sabah’s so-called ‘Lost World’ lies in south-central Sabah, about 40km north of the Indonesian border – an enclosed 390km² basin up to 25km across. The area is drained by tributaries of the Maliau River, one of which forms a stunning series of waterfalls, the seven-tiered Maliau Falls. It is a remarkable block of tropical forest – virtually the entire catchment of the Maliau River – almost encircled by a dramatic escarpment rising over 1,600m in height, insurmountable from most directions. The area was originally set aside by the Sabah Foundation and then formally upgraded to a Class 1 Reserve.

The basin has 12 different forest types, mostly Agathis tree-dominated lower montane, dry heath forest and lowland and hill dipterocarp forest. It is a faunal haven with over 1,800 species of plants and lots of wildlife including barking deer, banteng, sun bears, proboscis monkeys, clouded leopards, pythons and many species of birds including the rare Bulwer’s pheasant, crimson-headed partridge and peregrine falcon. Only a couple of operators are allowed to visit this area – it is under tight wraps, and is very expensive – about RM4,000–6,000 for five days and four nights excluding airfares, less with a bigger group. It’s also a tough trip – camping in tents, with lots of leeches around (including tiger leeches) and 06.00 starts. With long walking days in humid conditions, participants must be physically fit, and mentally prepared. There are about 12 licensed tour operators, both local and international, who can visit the area.

Niah Caves

Rising up dramatically behind the small township of Batu Niah, the 388m massif of Gunung Subis dominates Niah National Park, enfolding the famous archaeological site of the Niah Caves within its limestone outcrops. First gazetted as a National Historic Monument in 1958, after the find of a 44,000-year-old skull at the entrance to the caves, 3,100ha of surrounding rainforest and limestone hills were swept into the park’s realm when it was created in 1974.

Most people visit for the day from either Miri or Bintulu, though the visitors’ accommodation facilities are among the better maintained of Sarawak’s parks. The discovery of coffins, urns, pottery, paintings, textiles, tools and ornaments in Niah show consistent habitation over thousands of years – the area within and around the caves is full of archaeological, cultural and natural history.

Semenggoh Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre

Sarawak’s first forest reserve, established in 1920, was converted into a rehabilitation centre for orangutans, honey bears and hornbills in 1975. ‘Semi-wild’ orangutans inhabit the sanctuary, having graduated up from the infant-oriented Matang Wildlife Centre. Visits revolve around feeding times (half an hour at 08.30 and 15.00). The viewing area is a 1km walk from the entrance, where a series of graphic images warn of the dangers of serious injury from inappropriate behaviour with the orangutans. Such interaction most commonly includes goading and teasing the animals with food, and simply getting too close for comfort.

Morning visits can be better, when the apes roam free prior to the afternoon feed. It is not uncommon to run into some on the reserve’s pathways – but keep in mind the previous caution and do not wander alone. The rehabilitation centre is part of the Semenggoh Nature Reserve, whose arboretum and botanical research centre displays fernariums, ethnobotanic and other gardens. Visits to the latter must be booked in advance.

Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre

One of Borneo’s orangutan-viewing hotspots, entry prices have soared here in recent years. ‘SOURC’ was set up in 1964 to rehabilitate orphaned orangutans who had lost their parents and their habitat through logging. The apes were brought here to be taught the necessary survival skills before returning to the wild. Operated by Sabah’s Wildlife Department, it has now branched out into tourism and education, as well as conservation of other species.

A boardwalk leads to the feeding platform, perched up in the trees about 25m from the viewing area. The number of orangutans to be viewed depends on luck – and whether the orangutan females’ favourite ‘Mr B’ is there. Once the huge apes are full of bananas and vitamin shakes, they set off to have a swing and a play. Macaques and gibbons also come for a bite to eat. This is a great way to get a close-up view of the ‘Man of the Jungle’ and his primate cohorts.

Related books

For more information, see our guides to Borneo:

Related articles

This isn’t one for claustrophobes.

Covering even more of the world than our guidebooks, forests are ubiquitous but almost always different.

Bizarreness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.