If Russia, as Churchill famously claimed, is ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma’, then Kyrgyzstan is a central Asian matryoshka doll of interwoven Turkic, Mongol and Slavic cultures that has been coloured by successive shamanistic, Islamic and communist traditions.

Laurence Mitchell, author of Kyrgyzstan: the Bradt Guide

Although a cliché, Kyrgyzstan is often referred to as ‘The Most Beautiful Country in the World’ – and you can see why. Hidden in the depths of central Asia, the yawning valleys, rolling alpine meadows, glistening alpine lakes and abundant wildlife of Kyrgyzstan really do make it one of the world’s most stunning holiday destinations.

Go trekking amongst the towering 7,000m peaks in the Central Tien Shan, travel to the multi-coloured Osh Bazaar and sample shashlyk and laghman, or take a trip to the enormous alpine Lake Issyk-Kul.

For more information, check out our guide to Kyrgyzstan

Food and drink in Kyrgyzstan

Food in Kyrgyzstan tends to fall into two main categories – Kyrgyz and Russian – although sometimes what is on offer is more of a hybrid of the two. Staying in homestays, the food prepared by the hostess is always plentiful, usually very tasty and generally there is little point in looking to eat elsewhere. Away from the larger urban centres, the dining-out options are usually rather limited.

Bishkek has a wide range of smart restaurants that sell Turkish, Italian, American, Chinese, Indian, Korean and Japanese food, in addition to the standard fare. Outside of Bishkek, the larger towns have a few upmarket restaurants between them, but generally food is sold at simple cafes, traditional chaikhanas or Russian-style canteens, stolovaya. Kyrgyz cooking is very meat-based and that meat is usually mutton, but sometimes beef is used, particularly for shashlyk. Chicken rarely finds its way into Kyrgyz cookery and when it does the quality is not usually very good. Horsemeat is highly thought of and horsemeat sausages, chuchuk, are a popular accompaniment to vodka sessions.

As Muslims, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Dungans do not eat pork, but it can be found at some Chinese and Russian restaurants. Fish is uncommon, apart from the smoked fish that is sold by the roadside near Lake Issyk-Kul.

Kyrgyz cuisine

Kyrgyz dishes that can be found more or less everywhere are shorpo, a mutton stew that always comes with a big chunk of bone with fatty meat attached; laghman, noodles with mutton and a spicy sauce; and manti, steamed mutton dumplings.

Shashlyk, the central Asian kebab of skewer-grilled mutton pieces, can be found almost anywhere; just look for the grill-man at the front of the café, as the cookingis always done outside. Plov is made from a simple mixture of rice, mutton, carrots and onions all cooked together in a big pot, which can be delicious when it is well-made. It is actually an Uzbek dish but it can be found throughout the country, especially in the south.

The Kyrgyz national dish of beshbarmak is more of a home-cooked festival food than a restaurant item but some restaurants offer it.

The ultimate Kyrgyz snack food is samsa, which are like Indian samosas but instead of containing spicy vegetables they are filled with mutton, onions and gravy. Samsi are generally sold directly from small bakeries, especially in the mornings and at lunchtime, and are a good takeaway snack or quick lunch. They can be very fatty and are best when hot and fresh.

Other cuisine

Popular Russian dishes include pirogi, fried ravioli-like pastry packets, and pelmeni, small ravioli served in a broth. Blini are pancakes, either sweet or savoury, that, if you are lucky, your homestay hostess might prepare for breakfast. Most Russian menus usually involve several different types of salad that utilise copious quantities of mayonnaise. One excellent and surprisingly delicious salad combination is grated beetroot and diced walnuts.

In addition to Kyrgyz and Russian food, Dungan dishes are also sometimes found in the north, especially in the Chui Valley, the Dungan stronghold. Dungan food is rather like Chinese food, but spicier. Ganfan, made of rice and meat, is probably the most popular Dungan dish and often sold at markets.

Vegetarians

Vegetarians will have a little more luck finding something to eat in Russian restaurants than in their meat-centred Kyrgyz counterparts, but overall it is fairly difficult to find much in the way of purely vegetarian dishes. Fortunately, local markets always have a good selection of fruit, vegetables, cheeses and tinned goods. Some homestay hosts are able to rustle up vegetarian dishes, given adequate warning. Bread, the staple carbohydrate in the area, is usually in the form of lepyoshka, a Russian flat unleavened loaf, or otherwise nan, the Kyrgyz equivalent. Both are delicious when fresh and far superior to the sliced, white variety found in supermarkets.

Drinking

By far the most popular hot drink is tea, either green, which is preferred by many Kyrgyz, or black, the Russian favourite. Placing an order for food in a restaurant, it will more or less be assumed that you wish to order tea as well, even if you have already ordered beers or soft drinks. Kyrgyz going out to eat think nothing of ordering beer, vodka and tea all at the same time. Tea is invariably cheap at only 10–20som for a pot, and drinking plenty of it is the best and safest way to ensure hydration where the water supply is questionable. Coffee, where it is found, is usually instant and quite horrible, although in recent years a number of cafés and restaurants with espresso machines have opened up in Bishkek and even in Osh and smaller towns like Karakol.

Beer is widely available and quite good, the commonest brand being Russian Baltika, which is numbered according to its strength – Baltika 0 is non-alcoholic, Baltika 3 (seemingly hard to find!) is moderately low gravity, Baltika 5 is reasonably strong, Baltika 7 is very strong and Baltika 9 is like rocket fuel. Another good Russian beer that is widely available is Sibirskaya Korona, and there are decent Kyrgyz brands such as Arpa and Akademiya that are served on draught. Kyrgyz bottled beers tend to be cheaper than Russian brands, although sometimes weaker and less reliable in flavour. The Steinbrau beers of Bishkek that are produced by an ethnic German brewery of the same name are excellent.

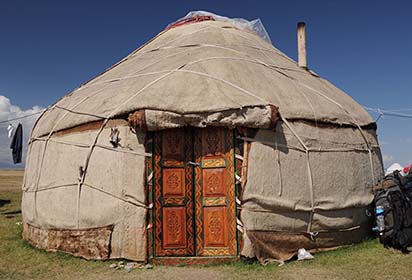

Other popular drinks are vodka (arak) and kumys, although the latter is not generally sold in cafés, as it is seen more as a homemade drink of the jailoos; it is, however, commonly sold at the roadside from yurts, especially in early summer. Bozo is a slightly alcoholic drink, made from fermented millet wheat, and Shoro is a well-known proprietary brand of maksym, a drink made from wheat. Kyrgyz wine is best avoided.

Health and safety in Kyrgyzstan

Health

Kyrgyzstan is a healthy place on the whole and although travellers should be prepared for any eventuality, you should not expect to fall ill here, excepting the odd bout of travellers’ diarrhoea. Nevertheless, all visitors to Kyrgyzstan should be in possession of adequate health insurance as state health care in Kyrgyzstan is rudimentary at best. Insurance is particularly important if such activities as trekking, horseriding or mountaineering are planned, and ideally should cover emergency medical repatriation.

There is a low-grade risk of malaria which is mostly due to Plasmodium vivax carried by female Anopheles mosquitoes. The risk is more common from June to October, mainly in areas bordering Tajikistan and Uzbekistan (Jalal-Abad, Batken and Osh provinces). Up-to-date advice on this situation and the need for prophylaxis should be sought from a doctor or travel clinic. At the time of writing, the risk is considered low enough to not need to take tablets but prevention with a DEET-containing insect repellent both day and night is always advised. In rural areas, and especially if cycling, dogs may be a nuisance and present the potential threat of rabies.

Although it is chlorinated, tap water is not of very good quality throughout the country and bottled or boiled water should be taken in preference. Thankfully freshly boiled tea is plentiful, abundant even, and perfectly safe to drink. Care should be taken with raw fruit and vegetables, particularly in the warmer months, and the standard recommendation to always peel or wash fresh fruit and vegetables is sound advice.

Cooked food such as meat stews that have cooled and have been standing around for a while may be more problematic, as might some of Kyrgyzstan’s dairy specialities such as kumys and kurut (dried yoghurt balls), which are sometimes plucked out of a horseman’s grubby pocket to be popped in the mouth of the appreciative visitor. Kumys – fermented mare’s milk – is generally not considered harmful (indeed many make claims to its health benefits), however, you should bear in mind that the fermentation process may not eliminate tuberculosis and it can upset the stomachs of those not used to its sour milk acidity and cause nausea and vomiting in the hapless visitor.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on ITSM. For other journey preparation information, consult Travel Health Pro (UK) or CDC (US). Information about various medications may be found on NetDoctor. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Theft

A few simple precautions will ensure that a visit to Kyrgyzstan is a safe and happy one. The countryside is mostly very safe in terms of human menace, although inebriated locals can sometimes be a nuisance. Larger towns, especially Bishkek, are another matter and caution should be taken after dark. At night the streets of all Kyrgyz towns and villages are generally pitch black with little – or nothing – in the way of street lighting and, putting the very real threat of tripping up over something to one side, there is a risk of mugging by locals whose resentment and coveting of the foreigner’s wealth is further fuelled by strong drink. It should never be forgotten that, compared with Europe and North America, Kyrgyzstan is a very poor country, and that most Western visitors walk around with more cash in their pockets than most Kyrgyz could possibly earn in a year.

Alcohol

Alcohol undoubtedly poses a serious social problem throughout the central Asian region; a problem that first came with Russian colonial rule, was ignored and partly contained during the Soviet period, and has been exacerbated by poverty and a general lack of hope since independence. Remarkably, vodka is available more or less everywhere at rock-bottom prices, even where there is little in the way of food to buy.

Heartfelt Kyrgyz hospitality is a wonderful thing but in all-male company it can sometimes quickly turn into little more than a kamikaze drinking session. It is crucial that moderate imbibers realise there is no such thing as ‘a small one’, ‘a quick one’, or ‘just one for the road’. An invitation to drink can be effectively the laying down of a gauntlet. The guest will be expected to keep up with the other drinkers and will find it difficult to detach himself from proceedings once a session is under way. It is considered very bad form to turn down further drinks once engaged in a boozing session and refusal may be seen as a grave insult to the host.

The best policy for those lacking livers of steel is to politely refuse in the first place, perhaps making something up on health reasons. This will not be popular but it sets the tone and will be respected. If you start drinking, then you will be expected to continue to the dregs of the bottle … and then maybe another.

Female travellers

The outward face of women in the country – both Kyrgyz and Russian – is one of self-confidence, independence and even feistiness. Even if this is not really an accurate picture, women travellers face no particular dangers in Kyrgyzstan. Sexual harassment is thankfully rare but, even though Kyrgyzstan is far from being a strictly Islamic regime, it is still unwise or insensitive to dress scantily and in a provocative manner, despite the many young Russian women in the cities who do just that.

Travellers with a disability

Apart from a few concessions in the capital, Kyrgyzstan has almost nothing in the way of facilities for disabled travellers. Exploring even Bishkek in a wheelchair would prove to be a challenge given the lack of ramps and poor condition of the pavements. On a more positive note, the majority of restaurants are ground-floor based, which is a slight advantage, and Bishkek’s top hotels at least have ramps and reliable lifts. However, outside of the capital it would be unwise to expect any facilities whatsoever. For those disabled travellers planning to visit Kyrgyzstan, hiring private transport and a guide through one of the agencies listed here is a virtual necessity.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Sexual acts between persons of the same sex have been legal in Kyrgyzstan since 1998 but same-sex unions have no legal standing. Kyrgyzstan, although more tolerant than neighbouring Uzbekistan and Tajikistan where homosexuality is illegal, remains a conservative country and, while gay relationships may be tolerated, open displays of affection between those of the same sex are frowned upon and may provoke hostility.

Despite recent changes in the law homophobia is still commonplace and there have been some reports of blackmail of homosexuals by corrupt policemen. The north is generally more easygoing than the south, and Bishkek, where a small gay scene has developed with a couple of gay bars/clubs, is the most tolerant. An organisation called Labrys, established in 2004, is dedicated to improving the lot of lesbians, bisexuals, gay men and transgender people in Kyrgyzstan. The age of consent in Kyrgyzstan is 16.

Travelling with a family

Like most people throughout the world, central Asians love children and travelling to Kyrgyzstan with a young family in tow will definitely win points in terms of popularity with the locals. Having said that, there may be some problems concerning hygiene with very young children, and the sometimes rather limited food available might prove problematic with those young travellers who are fussy about what they eat. The typical home cooking of homestays, with plentiful fruit, jams and baked goods, is likely to be more popular than standard restaurant fare. Independent travel in Kyrgyzstan can be hard work at times, with long, uncomfortable journeys that have few rest breaks.

This type of travel is probably too onerous for the average child; hiring a car with a driver would be a much better bet, allowing regular breaks and toilet stops (although probably not toilets) and the opportunity to stop whenever something of interest is seen. Most children will naturally love some aspects of the country like its horses, plentiful wildlife and colourful markets, and the beaches of Issyk-Kul are also likely to be popular with most young travellers. On the other hand, few children will patiently spend hours examining Silk Road monuments or archaeological sites, and even fewer will be willing to spend long hours energetically hiking in the hills.

Travel and visas in Kyrgyzstan

Visas

Since July 2012 visitors from the European Union (except Bulgaria and Romania), North America and Australasia no longer need a visa to visit Kyrgyzstan for a period of up to 60 days. The same waiver also applies to citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Monaco, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, Cuba, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Mongolia, Brunei, most Gulf Arab states – Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, UAE, Saudi Arabia – Russia and former countries of the Soviet Union. If planning to stay longer than 60 days a visa will be required, which should be obtained either in advance at a Kyrgyz embassy or on arrival at Manas airport.

For those passport-holders of countries that do require a visa – mostly African, Middle Eastern, South Asian countries, China and some South American countries – these can be obtained in advance at a Kyrgyzstan embassy. Most will be required to obtain a visa support letter from the Consular Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs if travelling for business purposes or, if travelling privately or for the purposes of tourism, an invitation letter (usually referred to as LOI – ‘letter of invitation’) issued by the Ministry of Internal Affairs. This additional paperwork can be issued, at a price and with some advance notice, by contacting one of the Bishkek travel agents listed. Visas are normally issued for 30 days.

Citizens of a small number of countries that require visas are able to obtain them without providing visa support or a LOI, and can obtain visas on arrival by air for between US$50–100 depending on length of stay and whether single or double entry. The countries not requiring visa support are: Albania, Andorra, Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, Cyprus, Indonesia, Israel, Macedonia, Mexico, Montenegro, Oman, Philippines, Romania, San Marino, Serbia, South Africa, Thailand, Venezuela and Vietnam.

Getting there and away

By air

Kyrgyzstan’s main international airport is Manas Airport in Bishkek (airport code: FRU; Tel: 693 109; Email: [email protected]) although a few flights from Russia also go direct to Osh. Manas Airport lies about 25km north of the capital, a 40-minute drive away.

From the UK

There are no longer any direct flights between the UK and Bishkek. British Airways used to fly three or four times a week to Almaty, a four-hour drive from Bishkek in neighbouring Kazakhstan, but this service was suspended in 2015.

The best way to reach Kyrgyzstan by air from the UK or elsewhere in Europe is to fly to Moscow or Istanbul and then transfer to a direct Bishkek flight. Flying via Moscow, there are flights with Aeroflot that change planes at Sheremetyevo airport. These start at about £400 return and fly daily but there is sometimes a long wait at the transit airport. A little more expensive, but more comfortable and reliable, are the daily flights with Turkish Airlines via Istanbul’s Ataturk airport, which start around £420 return. Another, usually less expensive Turkish alternative is with the budget carrier Pegasus Airlines that flies daily to Bishkek from London Stansted via Istanbul’s Sabiha Gökçen Airport. These flights can cost as little as £330 return and represent a real bargain, even if you do have to buy all your own drinks and meals on board. Because of seasonal demand flights tend to be more expensive during the peak months of July and August and so it is wise to book as far ahead as possible. Flying Air Astana, with a transfer in Astana, Kazakhstan, is another option from London.

From Europe

Other than BMI flights from London, the only other direct flights from Europe are with Turkish Airlines, which fly daily from Istanbul, and regular flights from Moscow with Aeroflot and other carriers. Flights to Bishkek from western European countries tend to connect with either Aeroflot in Moscow or Turkish Airlines in Istanbul. In Germany, Lufthansa do not fly to Bishkek but do regularly fly to Almaty in Kazakhstan.

From Russia and CIS countries

Kyrgyzstan has regular direct flights from Moscow with Aeroflot, Ural Airlines, Air Manas and Avia, as well as three times a week from St Petersburg, twice a week from Krasnoyarsk, three times a week from Yekaterinburg, and weekly from Novosibirsk and Omsk in Siberia. There are flights four times a week from Dushanbe in Tajikistan, with both Avia and Tajik Air, as well as regular flights to Tashkent in Uzbekistan and Almaty in Kazakhstan. Air Manas has regular flights to Tashkent, while Air Astana also flies to Bishkek from Almaty and Astana.

From elsewhere, China Southern Airlines flies to Bishkek several times a week from Ürümqi in Xinjiang. There are also flights from Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia with Turkish Airlines and Dubai with the budget carrier Fly Dubai. Air Manas also has regular flights from New Delhi and Kashgar.

From the USA and Canada

There are no direct flights. Flights from North America can either link with the direct BMI service from London to Bishkek or alternatively go via Moscow (Aeroflot) or Istanbul (Turkish Airlines).

From Australia and New Zealand

Probably the easiest way to reach Kyrgyzstan from Australasia or Southeast Asia is to fly to Tashkent via Bangkok and then either take a connecting flight or, politics permitting, travel overland to Kyrgyzstan.

By train

The great adventure of arriving in Bishkek by rail may not quite be as romantic as its sounds. It is a very long journey and there is an awful lot of dull Kazakh steppe to stare at before Kyrgyzstan is reached. In addition, some of the passengers travelling in platskart (third class) are smugglers, and some consider that it is not a safe journey for foreigners to take, at least in the lowest class.

In theory, at least, it is possible to reach Bishkek by train from anywhere in Europe by way of Moscow and the service from there. Naturally, having to travel through both Russia and Kazakhstan en route, there are going to be visa issues to consider. Train number 18, the Kyrgizia, leaves Moscow’s Kazan station twice a week on Thursday and Saturday at 22.40, to arrive just over 72 hours later in the late evening of the fourth day. This currently costs about 14,000 roubles (£170) in platskart (third class open carriage) and about 20,000 roubles (£240) in kupe (four-berth sleeper) if tickets are bought at the station. Booked through an agency they will cost considerably more. Trains number 17 and 27 to Moscow from Bishkek leave on Monday and Wednesday at 09.17 and take just over 73 hours to reach Moscow.

Rather than going all the way to Bishkek it is possible to leave any of the trains at Taraz (Dzhambul) in Kazakhstan and then enter Kyrgyzstan’s northwest Talas Province by minibus, saving five hours on the overall train journey.

Another alternative is to travel by train from Moscow to Almaty, although the direct service was discontinued in 2017 and the journey now requires a change in Saratov. In the summer season trains run once a week on Thurs evenings between Tashkent and Bishkek continuing to Balkychy but they are very slow (19+ hours to Bishkek, 24+ hours to Balykchy) and take a meandering route through Kazakhstan.

By road

From Kazakhstan

There are frequent services between Almaty and Bishkek by share taxi (2,500 Kazakh tenge) and marshrutka (1,500 Kazakh tenge) taking about five hours. The border is open 24 hours a day. From Taraz (Dzhambul) there are regular minibuses that connect with Talas in Kyrgyzstan’s northwest. Having been closed for three years between 2010 and 2013, the Karkara Valley route between Kegen (Kazakhstan) and Ken-Suu/Tyup (Kyrgyzstan) is now open again between mid-May and mid-October, although the exact dates tend to vary. Public transport on the Kazakh side goes as far as Kegen (around $10 per person in a share taxi from Almaty) from where taxis to the border can be caught (around $10). On the Kyrgyzstan side, it is usually possible to find a ride 20km to the village of Sary-Tologoy for around 1,500som. A daily minibus runs between Sary-Tologoy and Karakol (80som).

From Uzbekistan

The northern route between Tashkent and Bishkek passes through Taraz in Kazakhstan, where there is usually a change of transport. A Kazakh transit visa is needed for some nationalities on this route. To reach Bishkek from Tashkent it may well be quicker and cheaper, if the border is open, to go first to Osh via the Fergana Valley and then fly to Bishkek from there.

From Dostlyk, near Andijan in Uzbekistan’s Fergana Valley, there are normally plenty of share taxis running to the Kyrgyz border close to Osh, from where a minibus (10som) may be taken into the city. Dostlyk may be reached either from Andijan or Tashkent by share taxi. This border is open 24 hours a day. There is another border crossing at Uch-Kurgan on the road between Karakol (not the Lake Issyk-Kul town) and Namangan but this tends to close periodically. No public transport passes through here anyway, so it is necessary to take a taxi both sides. There is also another Fergana Valley crossing from Uzbekistan at Khanabad, just to the south of Jalal-Abad, but this also closes periodically. Although there are further crossing points between the two countries in the Fergana Valley, most of these will not allow foreign travellers through as they may be designated for locals only.

From Tajikistan

There is no regular transport along the Pamir Highway between Murgab and Osh, although private 4×4 vehicles may be hired for this route in either direction. Travelling this route requires a Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) permit in addition to a Tajik visa. There are share taxis between Isfara in the Tajik section of the Fergana Valley and Batken in southwest Kyrgyzstan; also between Khojand and Isfana in far south-western Kyrgyzstan. The Kyrgyz-Tajik border between Garm and Daroot-Korgon has been closed for foreign nationals for several years but it may become open at some stage in the future.

From China

There are two overland routes to and from China. The Torugart Pass in the southern Naryn province is technically closed to foreigners but permission to cross is granted if travellers have pre-arranged transport meeting them on the other side of the border and have documentation to prove this. The public bus that plies this route between Kashgar and Naryn cannot be used by foreign nationals. Further south, the Irkeshtam border, to the east of Sary-Tash in Osh province, permits crossing in either direction without any special conditions or documentation. A public bus normally runs between Kashgar in China’s Xinjiang province and Osh twice a week in both directions and takes at least 18 hours overnight. It is available for all to use.

Getting around

Getting around Kyrgyzstan is reasonably straightforward between the major centres – Bishkek, Karakol, Naryn, Jalal-Abad and Osh. Public transport tends to be a little erratic at times and some of the roads are in poor condition although they have noticeably improved in recent years. Hiring a taxi for a couple or small group for long distances is a relatively cheap and fast way of getting about. Self-drive car hire is also slowly becoming more popular. Given Kyrgyzstan’s pot-holed roads, its eccentric driving habits and a police force keen to extort fines from their motorised victims, car hire is not for everyone but it undoubtedly affords a great deal more flexibility and spontaneity than is ever possible by public transport. Flying may be a viable option for some north–south travel as it is markedly quicker and may be only a little more expensive than travelling by road.

By bus and minibus

Other than for local city services, very few buses operate in Kyrgyzstan these days. Most long-distance bus services have now been superseded by minibuses (marshrutki) running the same routes, which are by and large quicker. Minibuses tend to congregate outside bus stations and leave when full, usually with about 12–18 passengers plus the driver. Some marshrutki that travel relatively short distances along fixed routes, such as those along the shores of Lake Issyk-Kul, operate rather like a local bus service and do not wait to fill up before leaving, as they constantly pick up and drop off all along their route.

By taxi

Kyrgyzstan’s taxis will go almost anywhere if you pay them: a road surface of little more than loose rocks and sheep holds little fear for the average Kyrgyz Lada or Zhiguli driver. Fares are loosely negotiable, but are usually about twice the bus fare multiplied by four, the number of passenger seats. In many instances there is no bus or minibus service and so a taxi is sometimes the only option. If there is a CBT network in the town or village they usually have drivers who are familiar with the funny ways of the tourist and knowledgeable about the sort of places that they wish to go. Taxis may be hired for less than the CBT rate in the bazaar, although this is very dependent on the language and negotiation skills of the client, as well as how desperate the driver is to find a fare.

More popular routes often have shared taxis running the same routes as the minibuses and buses. They are effectively the same as ordinary taxis except they run the same route regularly and aim to fill the car with four passengers who all with less than a full complement of passengers if those present agree to pay for the empty seat(s) between them. Other than flying, shared taxis are the best way to travel between Osh and Jalal-Abad and Bishkek. They tend to cost less heading south than they do returning to Bishkek. Typical shared taxi fares are Bishkek–Osh, 800–1,000som; Osh–Bishkek, 1,200som.

When to visit Kyrgyzstan

When to visit

With its tough, continental climate, Kyrgyzstan is very much a seasonal destination. Unless travelling to the country for purposes of business or winter skiing, most visitors tend to come between May and October. For those whose interest is primarily in outdoor pursuits, the peak trekking season is a little shorter – between early June and mid- September. The period from mid-July to late August is by far the busiest with overseas visitors, partly because of the climate and partly as a result of this being the main European summer holiday season.

Given complete freedom of choice in deciding when to come, it really depends on exactly what the visitor wishes to do and where they want to go. For trekking, the higher the altitude, the shorter the season, tends to be the general rule, and so those wishing to do high-altitude treks in the Central Tien Shan are realistically limited to July and August. Lower-level treks are usually possible between June and September, although snow is always a possibility at passes above 3,000m at virtually any time of year. If it is snow that the visitor is actively seeking, for winter sports like skiing or snowboarding, then January and February are generally the best months to come, although early January can get very busy with winter vacation visitors from Russia and Kazakhstan.

The south of the country has a warmer climate in general and the low-lying Fergana Valley can be very hot during the summer months. Even Bishkek can be unpleasantly muggy in August. If these are the prime destinations to be visited it makes sense to plan a trip for spring or autumn.

If no high-altitude hiking is to be attempted, coming slightly out of season has its benefits. The northern shore of Lake Issyk-Kul, particularly Cholpon-Ata, can become very crowded in August, mostly with Kazakhs rather than European visitors; however, a visit in late September or early October is a wholly different matter, with few tourists, blue skies, turning leaves and a light dusting of snow on the mountains. It is too cold to swim at this time, however. Early autumn is actually a very beautiful time to be in Kyrgyzstan, especially if visiting southern destinations of modest altitude, such as the Lake Sary-Chelek region and Arslanbob, which has its walnut harvest at this time of year. Nights may be quite cold but there are warm days with clear blue skies.

Spring is a little less certain, as it can take time for winter snow to thaw completely, and late snowfall can mean many passes and even parts of the main Bishkek–Osh highway are under snow until mid-May. The months of April, May and June have the highest amount of rainfall, and this, coupled with melting snow, can sometimes pose risks of landslides and avalanches. Because of this, trekking conditions at the end of the season are usually a little more reliable than those at the beginning.

Holidays and festivals may also have some bearing on the timing of a visit. Nooruz, the ancient, Zoroastrian-influenced festival celebrated throughout central Asia on 21 March, is well worth witnessing, although this is rather too early to see the country at its best. Horse games tend to take place during high summer, especially around Independence Day at the end of August, and special festivals that involve horse sports, Kyrgyz crafts and music are staged at upland jailoos (meadows) during July and August for the benefit of visitors and locals alike.

Climate

Kyrgyzstan’s climate is partly influenced by its mountains and partly by its continental location far from any ocean. For the most part it is continental, with cold winters and warm summers. In the lowlands, the temperature ranges between –4°C KYR2.indd 4 28/09/2011 12:40 5 and –6°C in January and between 16°C and 24°C in July. The coldest temperatures are in the mountain valleys where –30°C is not uncommon and a record of –53.6°C has been measured, although –14°C to –20°C is more usual.

In the summer in the Fergana Valley, the average temperature in July is around 27°C, although temperatures frequently reach the low 40s. Even in the summer, temperatures may drop as low as –10°C at night on the mountain peaks. Of the major urban centres, Naryn has by far the most extreme climate, with an average minimum temperature in January of –19°C and an average maximum July temperature of 25°C. Both Bishkek and Osh have much milder winter temperatures but warmer summers. Generally temperatures are far less extreme in the region of Lake Issyk-Kul, where the presence of a large body of non-freezing, slightly saline water has a moderating influence on the local climate. Rainfall is generally fairly low throughout the country – as little as 100mm per annum on the southwest shore of Lake Issyk-Kul, to around 2,000mm in the mountains above the Fergana Valley.

The national average is 380mm, with March to May, and October and November usually the wetter months. There is sometimes heavy snowfall in winter. Clear skies are common and Kyrgyzstan averages more than 300 sunny days per year. Recent years have brought a number of unusual climatic events, which are possibly linked with worldwide climate change and glaciers receding: droughts in the Fergana Valley and elsewhere, low winter snowfall, unusually heavy rain in the spring and an increase in the water level of Lake Issyk-Kul, despite a preceding trend in which the water level was dropping.

What to see and do in Kyrgyzstan

Ala-Archa Canyon

This rugged, yet accessible, valley and gorge lies immediately south of the capital. Most of it belongs to the 120,000ha Ala-Archa National Park, created in 1976, and is nominally protected to some extent. The park has everything that you might expect of an alpine zone – snow-capped peaks, fast-flowing streams, alpine meadows, pine forest and steep crags – and it can seem remarkable to find so much unadorned nature so close to a capital city.

Ala-Archa National Park’s proximity to Bishkek is part of what makes it so popular © Mass Ave 975, Wikimedia Commons

Having said this there are less pleasant reminders that the metropolis is nearby, mostly in the form of litter, but this is only around the trail heads. It is this very accessibility that is actually the park’s greatest draw, especially to foreign expatriates and Bishkek’s middle classes who come here to picnic. As well as a convenient spot for picnicking weekenders, the park is also a magnet for hikers, skiers and mountain climbers.

Altyn Arashan Valley

Running parallel to the Karakol Valley to the east, but separated from it by the ranges of Kara-Beltek, Aylanysh and the high 4,000m-plus peaks of the Terim-Tor, is the Altyn Arashan (‘Golden Spa’) Valley. Of all the valleys which lie close to Karakol, this is probably the most popular overall, and with good reason. Even by Kyrgyzstan’s high standards, the valley is extraordinarily lovely, with silver threads of streams trickling down to join the Arashan River, lush meadows sparkling with wild flowers, and smooth green slopes cloaked by dense stands of conifer higher up.

Heading up the valley, the view is dominated by a picture-perfect view of the snow-topped 4,260m Palatka (‘Tent’) peak that lies far to the south beyond the Altyn Arashan hot springs that give the valley its name. Bears are said to inhabit the area, although there does not seem to be any record of attacks on humans in the region. The area includes the Arashan State Reserve, a botanical research preserve. The valley begins close to the village of Teploklyuchenka, to the east of Karakol town. Just south of the village the road splits, veering left to reach the spartan Ak- Suu sanatorium and continuing straight on for the Altyn Arashan springs, along a steep, and extremely rough, 12km track through pine woodland close to the Arashan River. The road is only suitable for a really tough 4×4 vehicle and is such a slow, uncomfortable drive that walking may be the longer but more appealing option.

Arslanbob

Arslanbob is central to one of Kyrgyzstan’s most remarkable regions – the vast relic walnut forest which stretches east and west of the village to cover a total area of 11,000ha. The large, sprawling village of Arslanbob serves as the market centre for the entire region as well as a summer resort with a gentle climate.

Arslanbob is surrounded by forests © Laurence Mitchell

Arslanbob is actually far more than this though: unusually for Kyrgyzstan, the village itself is a highly attractive place with a population that is almost entirely Uzbek, and with gorgeous mountain scenery, friendly locals and a pioneering local CBT group, it is hard to beat as a base for hikes in the hills that surround the village or as a start or end point for more energetic treks deep into the mountains.

Bishkek

One story relates that Kyrgyzstan’s capital, Bishkek (Бишкек), takes its name from the plunger of the wooden churn (bishkek) used to make kumys, the popular Kyrgyz tipple that is conjured from fermented mare’s milk. This is far from certain, however, as there are several plausible alternatives: another possible derivation might be from besh kek, which translates literally as ‘five chiefs’, or even besh bik, which is Kazakh for ‘five peaks’; or the name may even have a more ancient etymology and derive from pishagakh, an ancient Sogdian term meaning ‘place beneath the mountains’.

Whatever the name’s origin, all of these appellations are of central Asian derivation, a fact that is at odds with the reality that Bishkek is clearly a Soviet city with a Russian – or, at the very least, the ghost of a Russian – soul. Like a scaled down version of its Kazakh rival, Almaty, Bishkek is a Russian city displaced several thousand kilometres to the east by the geography of empire: a purpose-built capital with buildings and monuments resonant of Europe west of the Urals.

Also, like the Kazakh capital, Bishkek has a remarkable amount of green space, with swathes of parks and woodland dotted about the city to soften the traffic noise and freshen up the air (the city is said to have more trees per person than anywhere else in central Asia). The streets – a textbook example of Soviet planning – are arranged on a grid system and, as in many provincial Russian or ex-Soviet cities, the boulevards and avenues that criss-cross the city are a tad wider than they realistically need to be to contain the traffic.

Central Tien Shan Mountains

The corner of the Kyrgyz Republic that wedges itself between Kazakh and Chinese territory to the east of Karakol is indisputably the country’s wildest and least accessible region. It is in this region that superlatives abound: the highest mountains, the coldest temperatures, the longest glaciers, the grizzliest mountaineers and the strangest natural phenomena. This is a region of ice, snow and unexplored peaks – too high and inhospitable even for most hardy Kyrgyz nomads. It is home to Kyrgyzstan’s highest peak (the second highest in the former USSR), the world’s fourth longest glacier, an amazing disappearing lake and, if you believe in that sort of thing, the remote location for the crash landing of a giant UFO.

Unlike the valleys closer to Karakol this is no place for gentle mountain hikes and is really only for committed, experienced mountaineers and those who avail themselves of the support services of guides and porters. Whatever the degree of tactical support enlisted, fitness and stamina are essential. Visiting the area requires a considerable commitment of time, energy and money, but those returning from time spent trekking in the region invariably insist that it is well worth it.

Karakol

Of all the towns in Kyrgyzstan, Karakol tends to be the one in which the majority of foreign visitors spend the most time. This is down to the fact that as well as possessing a number of sights and monuments worth seeing, Karakol is also ideally situated for forays into the mountains to the south that beckon so tantalisingly from the town. Because of this, Karakol represents one of the focal points, perhaps the focal point, of Kyrgyzstan’s tourist industry and has, more than anywhere else in the country, including even Bishkek, a well-developed tourist infrastructure concerned with outdoor and adventure pursuits.

Having said that, Karakol remains low-key in the extreme; as yet, there are no brash hotels, fancy restaurants or lurid nightclubs. It is a delightfully serene sort of place, still resonant with the ghosts of 19th-century rural Russian life (along with the odd phantom from the Soviet period), and with an ambience that, paradoxically, feels both homely and comfortable and frontier-like.

Karakol Valley

This stunning valley lies immediately south of Karakol along the river of the same name that passes through the town. The valley has a ski base, which is visited by local and Russian skiers in winter, while in the summer it is a popular area for trekkers and campers. There are no villages anywhere along the valley, nor any facilities for tourism other than a summer tent camp, but this makes it all the more desirable as an ideal location for independent campers who bring all they need with them.

The Karakol Valley is one of the prettiest in Kyrgyzstan © Ondřej Žváček, Shutterstock

The Karakol Valley has been awarded national park status and there is an entrance fee to pay (250som for foreigners, 50som per vehicle). Beyond the entrance, a track leads up to the left along the course of the Kashka-Suu tributary to reach the ski base. The dirt road continues along the river to reach a wooden bridge across the river, where the track continues along the valley with the river to the left. The steep slopes here are covered with stands of spruce and the distinctively pyramid-shaped Tien Shan fir, while the grassy fringe beside the track is carpeted with herbs and wild flowers.

Lake Issyk-Kul

Lake Issyk-Kul, the second-largest alpine lake in the world (Lake Titicaca in Peru/Bolivia is the largest), gives its name to the oblast that surrounds the lake’s shoreline and extends across the high Tien Shan range south to the Chinese border. Issyk-Kul Oblast, which in area makes up around 20% of Kyrgyzstan’s territory, has a population of less than 500,000, the vast majority of whom live around the lake’s shores.

The lake’s name, which is also spelled Ysyk Kol or Issyk-kol, means literally ‘warm lake’ in the Kyrgyz language, as does its Chinese equivalent, Ze-Hai. There is good reason for this: in a part of the world where winter temperatures can plummet to -25°C or worse, the shores of the lake have a microclimate that is relatively balmy and, even more aptly, its waters never freeze. This is all the more surprising considering the lake stands at considerable altitude – 1,606m above sea level. Scientists have long debated the precise mechanics of this, and it would seem it is down to a combination of deep-water physics, slight salinity and underground thermal activity. Most locals are less questioning and are merely grateful for the respite the lake offers, assuming it is because the water is warmed by heat wafting up from the earth’s core.

Lake Sary-Chelek

Lake Sary-Chelek is one of Kyrgyzstan’s true gems – a major draw that is a little difficult to reach but, as most visitors seem to attest, is well worth the effort. Sary-Chelek (literally ‘Yellow Bucket’) is a fairly small, alpine lake set amid conifer, and relict fruit and nut forest at an altitude of 1,873m. The lake is just one part of the Sary-Chelek Biosphere Reserve which has seven lakes in total and protects more than a thousand species of plants, 160 birds and 34 mammals, including rarities such as bear, lynx and snow leopard.

Sary-Chelek is relatively small: just 7.5km long and 1,500m wide at its broadest point, with a maximum depth of 234m. The lake is fed by the Sary-Chelek River, in addition to numerous other streams and underground sources, and its outflow travels into the Kara-Suu. The hollow that the lake sits in was probably created by earthquake activity hundreds of years ago, although the precise geomorphology of its formation is unclear. The name ‘yellow bucket’, although hardly romantic, is perfectly apt, as in early autumn the turning leaves of the forest that surrounds the lake positively glow with golden-yellow light that contrasts sharply with the deep blue-green of the water.

Although you would not know from looking at it, Osh is Kyrgyzstan’s oldest city. As Kyrgyzstan’s second-largest city, with a mixed population of around 250,000, it is considered to be the capital of the south and has served as the administrative centre of the oblast since 1939. It is a lively city which, despite its smaller size, can seem busier than Bishkek. It has the largest mosque in the country and one of the largest and most crowded markets in all of central Asia. Central to the city is the steep outcrop of Solomon’s Throne, which is an important Muslim pilgrimage site, as well as a popular place for locals and visitors alike to enjoy the view over the city.

Osh

Despite being smaller than Bishkek, Osh often feels like the busier city © Hans Birger Nilsen, Wikimedia Commons

The city has a strong Uzbek presence and in many ways looks westwards towards the Uzbek Fergana Valley rather than north to the capital Bishkek. The Uzbekistan border is just a few kilometres from the city, a ten-minute marshrutka ride away. However, international wrangling between Kyrgyzstan and its immediate neighbour has meant that from time to time border crossings are not always as straightforward as they might be.

Saimaluu-Tash Petroglyphs

The name means ‘embroidered’ or ‘patterned stones’ in Kyrgyz and this is not a bad description for what is the most remote, and certainly the most spectacular, collection of petroglyphs in the country. Here, high on a lonely alpine plateau, are an estimated 11,000 petroglyphs scattered over the slopes of two glacial moraines that have been named by archaeologists, not very imaginatively, as Saimaluu-Tash One and Saimaluu-Tash Two. The larger of the two, Saimaluu-Tash One, measures 3km in length.

The petroglyphs at Saimaluu-Tash are the most spectacular in all of Kyrgyzstan © Pikozo.kz, Shutterstock

The petroglyphs, which are etched onto shiny basaltic stone, date from at least as early as 2000BC in the Bronze Age, and may well be even older. They most probably represent votive offerings that were brought to this sacred site from the valleys below. The site itself has undoubtedly long been considered to be sacred and it is believed the small pond that lies in the middle of the lower gallery was frequented by shamans.

Tash Rabat

Tash Rabat is probably Kyrgyzstan’s most remarkable monument; indeed, it is one of the most interesting sites in the entire central Asian region and its presence is in complete contradiction to the popular tenet that Kyrgyzstan is all about landscapes rather than historical sights.

Tash Rabat is a Silk Road monument par excellence: a small but perfectly formed 15th-century caravanserai that sheltered an array of merchants and travellers along one of the wilder stretches of the Silk Road. Its location is even more remarkable: tucked away from sight, half-buried in a hillside, up a valley at 3,530m above sea level.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Kyrgyzstan:

Related articles

From boiling lakes to vast alpine bodies of water, these are our favourite lakes from around the world.

Discover our favourite sights along one of the most important trading routes in history.

Exploring one of our favourite regions with our Photographer of the Month, Cynthia Bil.

Exploring the country’s cultural heritage, from Silk Road monuments to deeply ingrained nomadic traditions.

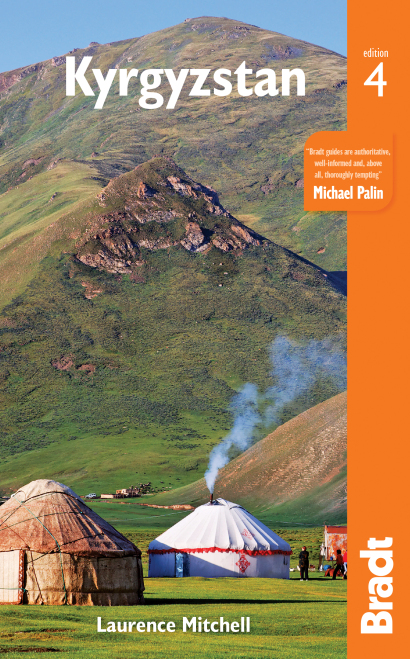

In Kyrgyzstan, the yurt is a pivotal part of both the nation’s past and present.

A tradition which goes back hundreds of years, eagle hunting is a dying practice of Kyrgyz life.

Lawrence Mitchell investigates one of the country’s strangest encounters.