Uzbekistan captures the imagination like almost nowhere else. The people, ideas and goods that travelled east to west, and, indeed, west to east, have left indelible marks on Uzbekistan’s landscape, its culture and the genetic make-up of its people, creating a diverse destination with layer upon layer of competing (but entwined) identities.

Sophie Ibbotson and Tim Burford, authors of Uzbekistan: The Bradt Guide

Uzbekistan is the most populous country in central Asia and the thudding heart of the Silk Road – betwixt its borders are all manner of marvels, the likes of which would make anyone stand and stare. The terrain varies starkly from the harsh western deserts and the empty, moon-like steppe to the lush, jade-green fields of the country’s bread basket, the Fergana Valley, and the striking, snow-capped mountains that surround it.

This is a country with a rich, fascinating past, and its long-settled history has left numerous physical remains, making it far more tangible than in neighbouring Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan, where nomadism was the norm. The country has been continually inhabited since Neanderthal man first walked across the steppe and took refuge in the Gissar Mountains south of Samarkand. His Stone Age descendants carved their marks in caves, and by the 1st millennium bc Iranian nomads had settled the grassy plains, planted crops and built rudimentary irrigation channels.

In their wake came wave after wave of invaders: Scythians, Achaemenids, Greeks, Arabs and Mongols. Each group built palaces, fortresses and places of worship and of trade, attempting to eclipse both physically and in public memory whatever had been there before.

The constant cycle of construction and destruction has had a significant impact on what we see in Uzbekistan today. The buildings that survive, and which make the striking skylines of each and every city, are not necessarily the most modern or the mostly strongly constructed: they are the ones which, by dint of good fortune, have avoided both the attentions of marauding hordes and equally destructive natural disasters.

In many ways, Uzbekistan is at a crossroads. This applies, as it has always done, in a physical sense, as the country lies in the heart of Eurasia: Europe and Iran are to the west; Russia is to the north; China is to the east; and Afghanistan and the Indian subcontinent spread out southwards. But it is also true culturally, economically and politically. Almost three decades after the fall of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan is no longer a bedfellow of Moscow, but neither has it been able properly to integrate with markets and potential allies in the West.

And yet history has shown that Uzbekistan is at its greatest when it has a symbiotic relationship with its neighbours, when people, ideas and goods flow back and forth, enriching society. After a period of relative isolationism, it is returning to the world stage. Since 2016, the country has grown in confidence and influence, actively courting foreign governments, businesses and tourists to visit, collaborate, trade and share the finest aspects of their respective societies for mutual benefit.

This alluring country is not only a destination for all seasons, but also for all kinds of tourist. Whether your dream holiday involves luxury hotels and peerless cultural sites, backpacking and buses, crossing the desert by camel or skiing and a first ascent, Uzbekistan really does have it all.

For more information, check out our guide to Uzbekistan

Food and drink in Uzbekistan

Food and drink in Uzbekistan food is typically Turkic, dominated by mutton, noodles and bread, but with many Persian flavours added, such as saffron, pomegranate, pistachio, almond and dried fruit.

Uzbekistan’s national dish is plov (also known as osh), an oily rice-based dish with pieces of meat, grated carrots, onions and, if you are particularly fortunate, roasted garlic and hard-boiled egg. It is typically only available at lunchtime, and is popular at weddings and other large celebrations when male chefs (oshpaz) cook huge quantities outdoors in giant dishes known as kazans.

Local variations are proudly maintained: in Bukhara plov is cooked in three separate cauldrons and mixed only when it is served, in Fergana two specific types of dezvira rice are used, with hot pepper and a pinch of cumin, and in Khiva it was originally made in a cauldron of hot sand. Plov is invariably washed down with green tea, its astringency helping to cut through the mutton fat.

Other notable national dishes include shurpa, a soup with fatty mutton and vegetables; norin and lagman, two mutton-broth soups with noodles that may also be topped with a piece of horse meat; dimlama, meat and vegetables stewed slowly in a tightly sealed pot; and the ubiquitous shashlik, grilled kebabs with cubes of mutton or beef and fat, which is considered to add to the flavour. For a quick snack, consider either manti (also called qasqoni and found across the Turkic lands), a steamed dumpling containing minced mutton, the similar chuchvara, or somsa, a fried or baked pastry parcel (not quite a samosa) that contains either mutton or, occasionally, mashed potato.

Every meal is accompanied by the flat, round loaves of bread known as non. The most common form, obi non, is cooked in a clay tandoor oven. Non is generally torn into chunks rather than sliced, and you should show respect by not placing it upside down on the table.

Vegetarians are in for a tough time: the concept is little understood, and even less frequently catered for. Meat-free versions of the classic Uzbek dishes tend to be pretty dull, but you should at least be able to get a Greek or achichuk salad, consisting of tomato, onion, cucumber and dill. Luckily, Uzbek breakfasts are excellent, with plenty of eggs, cheese, bread and fruit, and will set you up for the day. If you are in Uzbekistan in summer and early autumn, the country is bursting with fresh fruits. Stalls in bazaars and by the roadside sell an amazing variety at knockdown prices.

An Uzbek’s veins run with tea as much as blood, and the chaikhana (tea house) is central to any community: people go to do business as much as to gossip and relax. Green tea (zilloniy chai) is most common in the provinces, but black tea (chorniy chai) is preferred in Tashkent. Both are available wherever you go, but expect a funny look if you want your tea with milk (tea with sugar is fine). In summer you may also be offered ayran or kefir (chilled yoghurt drinks).

Health and safety in Uzbekistan

Health

The medical system in Uzbekistan is seriously overstretched. The quality of medical training has fallen since the end of the USSR era: many doctors have left to find work abroad, hospitals are rundown and equipment is out of date. Outside the major cities there is also a shortage of drugs and other medical supplies.

If you are ill or have an accident, you will be able to receive emergency treatment at one of the good private hospitals in Tashkent or at a more basic regional hospital, but will then require medevac to a country with more developed medical infrastructure for ongoing care, either in Europe or India. British citizens should be aware that the reciprocal health-care agreement between the UK and Uzbekistan ended in 2016.

Every town in Uzbekistan has countless pharmacies (marked ‘Apteka’ or ‘Darikhana’), selling a range of generic drugs. You do not need a prescription to purchase medication but should read the instructions carefully (or get someone to explain them to you).

It’s illegal to bring codeine, Valium, Xanax and Temazepam into Uzbekistan – nowadays customs officers are unlikely to look too hard, but it’s best to bring the prescriptions for your medicines and to keep them in their original packaging.

Safety

The UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) generally considers Uzbekistan to be a safe place for foreigners to travel. They regularly update their travel guidance, and it is advisable to check this as issues such as Covid-19, natural disasters, and border openings/closures may influence how and when you travel.

The FCO advises caution when travelling to border areas, in particular the border between Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, as there is a threat of land mines. These regions can also be flashpoints for inter-ethnic violence, as was seen in the Fergana Valley in July 2010. Such violence is not typically targeted at tourists, but there is a risk of being caught up in the upheaval.

Uzbekistan is seismically active, and there is therefore a risk of earthquakes. On 20 July 2011 an earthquake measuring 6.2 on the Richter scale hit Batken, just across the Uzbek border with Kyrgyzstan, and tremors were felt in Tashkent. A number of deaths and injuries were reported. This was the country’s most recent serious quake, although there have, of course, been tremors.

Female travellers

Uzbekistan is generally a safe country for women to travel in, and there are no specific legal or cultural restrictions imposed on women (either locals or foreigners). The social conditions of women improved significantly during the Soviet period, and the enrolment of women in education and in the workplace remains high. Gender roles remain traditional but relaxed.

You should dress modestly, especially in conservative rural areas and in the Fergana Valley where religious sentiments often run high.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Homosexuality is illegal in Uzbekistan and Article 120 of the country’s penal code punishes voluntary sexual intercourse between two men with up to three years in prison. Sexual intercourse between two women is not mentioned in the code.

Many people in Uzbekistan are deeply conservative, especially when it comes to the issue of sexuality, and homosexuality is still often seen as a mental illness (a hangover from the Soviet period). Homosexuals in Uzbekistan regularly experience harassment, including from the police, who heavily monitor gay-friendly establishments, often forcing them to close. Police detention and the threat of prosecution are regularly reported.

If you are travelling with a same-sex partner, you should refrain from public displays of affection and be exceptionally cautious when discussing your relationship with others: it is often simplest to allow others to assume you are simply travelling with a friend. Double rooms frequently have twin beds, so asking for one room is unlikely to raise eyebrows in any case.

Travelling with a disability

Travellers with disabilities will experience difficulty travelling in Uzbekistan. Public transport is rarely able to carry wheelchairs, few buildings have disabled access, and streets are littered with trip hazards such as broken paving, uncovered manholes and utility pipes. Hotel rooms are often spread over multiple floors without lifts and assistance from staff is not guaranteed. If you have a disability and are travelling to Uzbekistan, you would be advised to travel with a companion who can help you when the country’s infrastructure and customer service fall short.

Travel and visas in Uzbekistan

Visas

Unless your country is on the visa-free list, you will need a visa (paper or electronic) before you fly. The easiest option is to apply for an e-visa, which costs US$20 and is valid for 90 days from the date of issue for a single entry and a stay of up to 30 days in Uzbekistan (but not beyond the expiry date of the e-visa).

Even if your country is on the visa-free list, a standard visa is required if you wish to visit other countries and return to Uzbekistan, or if you wish to stay in the country for more than 30 days. To get one, fill out the online application form and print it. Be sure to sign it in black ink as this box is easily overlooked. Submit the form with two passport photos, a photocopy of your passport and the passport itself to the embassy.

Getting there and away

For somewhere so centrally located geographically, Uzbekistan can be surprisingly challenging to reach. There is a shortage of direct flights from Europe and the US, land borders open and close on a whim, and arriving by train requires a passport full of transit visas and the patience of a saint.

By air

The vast majority of visitors arrive in Uzbekistan on a flight to Tashkent and this is, on balance, the easiest way to travel. With the exception of Uzbekistan Airways, direct flights to Uzbekistan tend to come only from the Middle East, Russia and the other CIS countries. Otherwise, you’ll probably have to get a connection in one of the regional hubs (Almaty, Istanbul or Moscow).

By rail

There is a certain romance attached to train travel, and if you have the time to sit and watch the world pass by at a leisurely pace (very leisurely in the case of the old Soviet rail network), it is still a viable way to reach Uzbekistan. Depending on your nationality, you may need transit visas for the countries en route.

Ticket classes are categorised in the Russian style. First-class accommodation (Spalny Vagon; SV or es-veh; also known as deluxe) buys you an upholstered seat in a two-berth cabin. The seat turns into a bed at night. Second class (Kupé) is slightly less plush, and there are four passengers to a compartment. Third class (Platskartny) has open bunks (ie: not in a compartment) and lots of interaction with fellow passengers. Bring plenty of food for the journey, and keep an eye on your luggage, particularly at night, as theft is sadly commonplace.

There are three trains a week between both Moscow and Tashkent and Almaty (Kazakhstan) and Tashkent. The Moscow service (train numbers five or six depending on the direction of travel) takes 62 hours, with tickets starting from US$166. The Almaty service is a modern Talgo train which takes 16½ hours, with tickets starting from US$14. There’s also a weekly train from Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan) to Tashkent, passing through Kazakhstan (20hrs 40min; tickets starting from US$55); it actually starts from Balykchy (formerly Rybachye), a resort on Lake Issyk-Kul. From Tashkent, weekly trains also run to Ekaterinburg, Novosibirsk and Ufa in Russia.

The train timetable for the whole Russian rail network (including central Asia) is online. The Uzbek Railways site, parts of which are in English, is www.uzrailpass.uz. The Man in Seat 61 also has detailed information, including personal reports, about train travel in the former USSR.

By road

Personally, we prefer to reach Uzbekistan overland, not because customs and immigration make it a particularly easy or pleasant experience, but because of the freedom having your own transport gives you once you finally make it inside. If you are bringing your own vehicle into Uzbekistan (regardless of the entry point) you will have to declare it on the usual customs form, plus fill in additional paperwork to be entered on to the computer system.

Theoretically at least, you will not be allowed to leave the country unless you take the vehicle with you. You may be told that right-hand-drive vehicles cannot enter Uzbekistan; this is not true so hold your ground. Expect to have the vehicle thoroughly inspected, sluiced with disinfectant, and to have all of its contents (sometimes right down to the jack and spare wheel) passed through the X-ray machine.

What to see and do in Uzbekistan

The Igor Savitsky Museum

Like a ruby in the dust, the Igor Savitsky Museum (also known simply as Nukus Museum) holds the world’s second-largest collection of Russian avant-garde paintings after the Russian Museum in St Petersburg. It also has one of the largest exhibitions of archaeological finds and folk art anywhere in central Asia.

The museum is currently divided into six sections among two buildings. You enter through the Archaeology and Ancient Khorezm gallery, where you will find some of the most significant finds from the various excavations in Khorezm, including from the fortresses.

The Applied Arts gallery is the core of the museum (at least in terms of quantity), with more than 70,000 items from the 19th and 20th centuries, many obtained by Savitsky in the 1950s, and it is believed that the relationships and reputation he formed collecting folk art gave him the credibility and network required to later purchase his avant-garde works.

The upper floor starts with Uzbek Art of the 1920s and 1930s, a comprehensive survey of schools from realism to avant-garde, including both Uzbek artists and foreign artists painting in Uzbekistan. The works show the important interplay of influences from East and West: architecture and decorative arts are drawn from Uzbekistan’s Islamic traditions; artists such as Benkov, Koravay and Kashina depict the region’s ancient cities; Nikolayev imaginatively blends the techniques of Italian masters and Russian iconography. There are also works of Impressionism, post-Impressionism and Futurism.

The collection continues with its most famous section, the 20th-century Russian Avant-Garde, a smorgasbord of post-revolutionary works that narrowly survived Stalin’s curtailment of creative freedom and prescription of ‘Social Realism’ as the only acceptable form of Soviet art in 1932. Art that did not conform with Stalin’s ideal was repressed and its artists persecuted.

The second building (quieter and rather chillier) starts with art from Karakalpakstan and early 20th-century Uzbekistan. The Karakalpakstan Contemporary Culture and Arts gallery aims to showcase and develop fine art in Karakalpakstan. Among the artists whose work is exhibited here are several of Savitsky’s students: J Kuttymuratov, B Serekeev, A Utegenov, E Joldasov and the sculptor D Toreniyazov, who based his style on traditional woodcarving. You can also see some of Savitsky’s own oils and watercolours in both buildings: he was a gifted painter in his own right, and indeed first came here as an artist.

Tashkent

Too frequently passed over in favour of the Silk Road’s UNESCO stars, Tashkent is a vibrant crucible of historic architecture and Islam, Soviet town planning and propaganda and 21st-century nation building. A stone’s throw from the capital in Tashkent and Syr Darya viloyati (provinces), the Syr Darya River carves up the steppe and cultivated lands. To the northeast of the city, the Ugam-Chatkal National Park, with its alpine meadows and mountain forests, is a welcome natural haven among the mines, factories and infrastructure projects that are driving the Uzbek economy forwards.

Tashkent morphs and expands with every new generation. With an official population of 2.5 million (although some estimates place it as high as 4.45 million), it is far and away the largest city in central Asia: only Kabul comes anywhere close. A stroll through any bazaar reveals the ethnic diversity of its people, with not only Uzbeks, Tajiks and Russians but also Crimean Tatars, Koreans, Bukharan Jews and other unexpected minorities each contributing to the city’s cultural smorgasbord.Though first impressions may be of chaos, concrete and cars, a stroll through the backstreets of the Old City or a rummage through Chorsu Bazaar reveal an older, slower way of life that continues to underpin modernity.

Hazrat Imam Complex

Northeast of Chorsu Bazaar is the historical spiritual heart of Tashkent, a glimpse of what much of the city must have been like before it was levelled by the 1966 earthquake or replaced with Soviet concrete. At its heart is Hazrat Imam Square (sometimes also written as Khast Imom Square).

Between here and the main road is the Hazrat Imam Mosque, constructed in just four months in 2007 on the instruction of President Karimov. Then the largest mosque in the city, it was an expensive undertaking: the sandalwood columns came from India, the dark-green marble is Turkish, and the interior of the blue-tiled domes is decorated with genuine gold leaf.

Amir Timur Square

The heart of the modern city, Amir Timur Square is a lush, green space with plenty of flowers and fountains, laid out in the 1870s. Roads radiate from here to the north, east and south of Tashkent, and the city’s most important buildings, both political and cultural, are concentrated on the square and in the immediate vicinity.

A large statue of Timur himself, sitting astride his horse and proclaiming ‘strength is in justice’, is the square’s current centrepiece, but he is simply the latest in a long line of former residents: General von Kaufmann, Lenin, Stalin and Karl Marx all occupied this spot before him. This particular statue, a 7m-high bronze by sculptor Ilhom Jabarov weighs in at 30 tonnes and is one of three erected in Uzbekistan to commemorate the 660th anniversary of Timur’s birth.

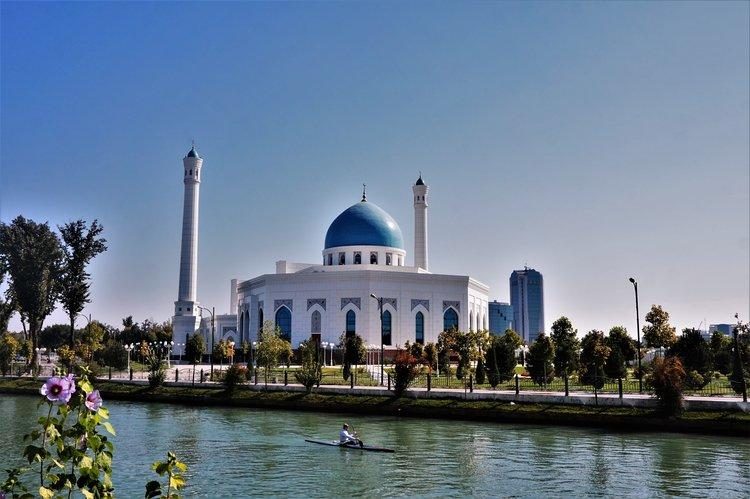

Minor Mosque

Uzbekistan’s largest mosque (not minor at all), opened in 2014, sits amid broad promenades by the embankment of the Ankhor Canal, a few hundred metres west of the Minor metro station, making it a popular spot for evening strolls and people watching.

It’s in traditional style but with far more white marble; the main hall with its gold-plated mihrab sits beneath a turquoise dome and the open front section brings its total capacity to over 2,400 people.

Shakhrisabz

There has been a settlement here, in the upper reaches of the Qashqa Darya River, for at least 2,700 years. The modern highway from Samarkand overlies a much older route across the mountains, but though it was a well-situated trading post, it would never have come to our notice if it were not for the city’s most famous son: the 14th-century emperor, Amir Timur.

Amir Timur dominates Shakhrisabz, and quite rightly so. Join the throngs of wedding goers in Amir Timur Park to have your photo taken with the modern bronze statue of the great man himself and, more importantly, to see what’s left of the Ak Serai, his once-mighty palace with its unrestored medieval tilework. Then head through the park to the Dor at-Tilyavat and Dor as-Siadat for the Timurid mosque and family necropolis.

There is very little in the way of practicalities here (including no ATMs). Everything is in limbo until the town recovers from the clearing of the Old Town and redevelopment – until then, bring essentials from Samarkand.

Dor at-Tilyavat Complex

This holy site (its name means Abode of Reverence) dates from the 1374 construction of the tomb of Sheikh Shamsiddin Kulyol, a revered Sufi teacher who is credited with converting the Chagtai tribes to Islam; he was joined by various other holy men, and this became an important destination for pilgrimages.

On the left/east side of the courtyard (lined with craft stalls) are two heavily restored blue-domed mausoleums (known as the Kosh- Gumbaz or Double Dome): the Mausoleum of Shamsiddin Kulyol to the left, and the Gumbazi Seidon (dome of the Sayyids) to the right, marking the graves of various Timurid-era reverends.

The aptly-named Kok-Gumbaz (Blue Dome), on the right side of the courtyard, was built by Timur’s grandson Ulug Beg in 1434–35, not long after his father had moved the centre of Timurid power from Samarkand to Herat, and is the town’s main mosque. On the site of an older, Karakhanid-era mosque, it once had a dome larger than that of the Bibi Khanym Mosque in Samarkand, as well as 40 domed galleries to house additional worshippers. The original dome collapsed in the late 18th century, but was rebuilt 200 years later.

Ak Serai Complex

At the northern end of Ipak Yuli is Timur’s Ak Serai (or Ok Saroy; White Palace), quite possibly the largest and most impressive building he commissioned. The portal alone would have reached 50m in height and been flanked by a pair of tapered minarets, each 65m tall.

Construction of the palace began in 1380 and it took the labourers and artisans, drawn from across the Timurid Empire, 24 years to complete. According to the Castillian ambassador Clavijo, the rear courtyard was 300 paces wide (in all an estimated 1.6ha) and the reception halls were painted azure blue and richly gilded. It must have been quite a sight.

Envisaging the scale and might of this structure today requires a little imagination. In their attempt to wipe out memory of the Timurids, the Shaybanids destroyed many of the original structures, leaving just 38m of the central gateway intact. This may not sound a great deal, but it still rises dramatically above the surrounding parkland and is visible from quite a distance.

Unlike many of Uzbekistan’s other historic sites, very little restoration work has been done here, and UNESCO’s emphasis seems, quite rightly, to be more on shoring up the building than touching up its magnificent (albeit time-ravaged) tile work. This approach enables you to appreciate what is original and what is a modern interpretation of the site, far more so than is possible in Samarkand.

Immediately in front of the gates is Shakhrisabz’s modern statue of Amir Timur. It’s biBg, it’s brash and it probably looks nothing like the man himself, but every bride and groom in the vicinity, plus their inebriated entourages, are clamouring to have their photos taken alongside. If you stray too close, expect to be enveloped into the fold and to have a glass thrust into your hand: foreigners are popular additions to wedding photographs, it seems, even if you’ve previously never met.

Chorsu Bazaar

Meaning ‘the crossroads’, Chorsu Bazaar is the commercial heart of Tashkent and has been for hundreds of years. Originally open to the air (as parts of it still are today), the maze of covered stalls was largely cleared away in the mid 20th century. In their place Soviet architects designed and built vast mosaic-covered domes, blue & turquoise space bubbles that still protect merchants and their goods from the elements and give the bazaar’s skyline its distinctive shape.

Each dome or area of the market houses a different type of merchandise: take a stroll around the dried fruit and nut stands if you want to try plenty of free samples but beware of the dried cheese balls: they’re something of an acquired taste. If you have the time to hunt, almost everything is for sale here: plastic Chinese household goods battle for attention with hand-painted ceramics and fox fur hats, almost-antique nick-nacks, dried fruits and imported car parts in varying states of decay.

You can of course buy a trailer-load of watermelons and 300 plastic buckets, but the real delight comes in spending an hour or three exploring the trading domes, drinking bowls of fragrant black tea, smelling the shashlik grilling and engaging in an animated, good-natured haggle for a bag of salted pistachios and a fresh, pink pomegranate. Come here for some well-placed souvenirs, including a wide selection of ceramics, and the best people-watching in Tashkent.

The market is liveliest first thing in the morning when the wholesale deliveries are made, and the cheap chai and kebab stalls provide ample sustenance while you watch the world go by. Come here to get a feel for ‘real’ Tashkent and an echo of Silk Road trade in centuries past.

Fergana Valley

The Fergana Valley is a depression between the Tian Shan Mountains in the north and the Gissar-Alai range in the south. Some 300km long, up to 70km wide and watered by the Kara Darya and the Naryn rivers, which join to form the Syr Darya, it is the most fertile part of Uzbekistan and hence the country’s agricultural heartland. Agricultural wealth historically gave rise to Silk Road trading towns, fortresses and, most importantly, the Khanate of Kokand, between 1709 and 1876.

For much of the past 100 years it has also been an area that is deeply troubled. Stalin’s border policies divided the valley between Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan; not only are there main international borders here, but also a bewildering number of enclaves and exclaves that are nigh on impossible to administer but are fiercely defended at great financial and human cost. Communal violence has regularly reared its ugly head, for instance between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in the summer of 2010, often spurred on by governments and other regional players when it suits their political objectives to do so.

Khiva

It is rare to come across an entire city that is a museum. Though Bukhara is packed with remarkable sites it is still nonetheless a living, working city. Khiva, however, is more akin to a film set, the local population, rightly or wrongly, sidelined in order to preserve historic buildings and present a manicured scene to tourists.

Whatever you feel about such a policy, Khiva remains one of the greatest cities on the Silk Road: the Ichon Qala in particular is a labyrinth of madrasas and mosques, minarets and trading domes that, at least on the surface of it, look just as they would have done at the end of the 19th century before Soviet town planners, demolition crews and modernist architects got their hands on Uzbekistan.

On a cold winter’s evening, after the wedding parties have departed and the few tourists are enjoying their supper, you can be entirely alone with the ghosts of the past, wandering the narrow streets and soaking up the atmosphere. Which decade, indeed which century, you care to imagine yourself in is entirely up to you.

Archaeological digs in the Ichon Qala during the 1980s and early 90s uncovered a wealth of material as much as 7m below the modern ground level, and the earliest finds from these excavations suggest that the town was first inhabited between the 6th and 5th centuries bc. Legend has it that the city was founded long before this, however, as Shem, son of Noah, is said to have first marked out the city’s walls.

Ichon Qala

The heart of the Museum City, the Ichon Qala seems like a time warp. Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1990, it is devoid of cars in its central areas, and with most of the modern infrastructure hidden from view, if you wake up and get out early, or take a walk late in the evening once the crowds have gone, then you’ll capture a glimpse of Khiva in a bygone age, albeit rather cleaner.

The density of sites, in particular the madrasas, means you’re unlikely to be able to take everything in, and regular refreshment breaks will certainly be in order. We’ve tried to provide a list here of the most important sites, though as seemingly every building has a story to tell, there’s no doubt you’ll chance upon plenty of others as well.

City walls

The crenellated city walls were Khiva’s first line of defence from medieval raiders. Some 2.2km (1.4 miles) surround the city centre, and at their most impressive point they are 10m high and 8m thick.

Built from adobe mud bricks, the oldest remaining sections of the walls date from the 5th century AD, though much of what you see is of far later (17th century) construction. Four substantial gateways allowed access through the walls; the sentries posted here would have been heavily armed, and closely monitored everyone and everything entering and leaving the city.

Islam Khoja Madrasa

At the start of the 20th century there were 65 madrasas in Khiva, 54 of them within the city walls. In many ways, madrasas are to Khiva as university colleges are to Oxford or Cambridge – being higher education institutions where teachers and students lived and worked together. As such, the city was a hotbed for religious education and religious debate, and its wealthier residents bid to outdo each other by building larger, richer and more elaborate madrasas.

The striking turquoise Islam Khoja Madrasa is a surprisingly late construction: it was completed only in 1908. Its founder, Islam Khoja, was grand vizier to the khan and an active educationalist. He introduced several educational reforms, endowed schools and hospitals, and his pièce de résistance is this building.

Sadly, the completion of the project is tied up in tragedy: Islam Khoja was assassinated in 1913 and the madrasa’s architect was buried alive by Emir Isfandiyar Khan as a potential witness to the murder.

The 42 rooms of the madrasa now house the Museum of Applied Arts. Though the selection of artefacts is not of such high quality as in similar museums in Tashkent and Bukhara, there are still some interesting examples of royal costume, metalwork, leather goods, tiles and carved marble.

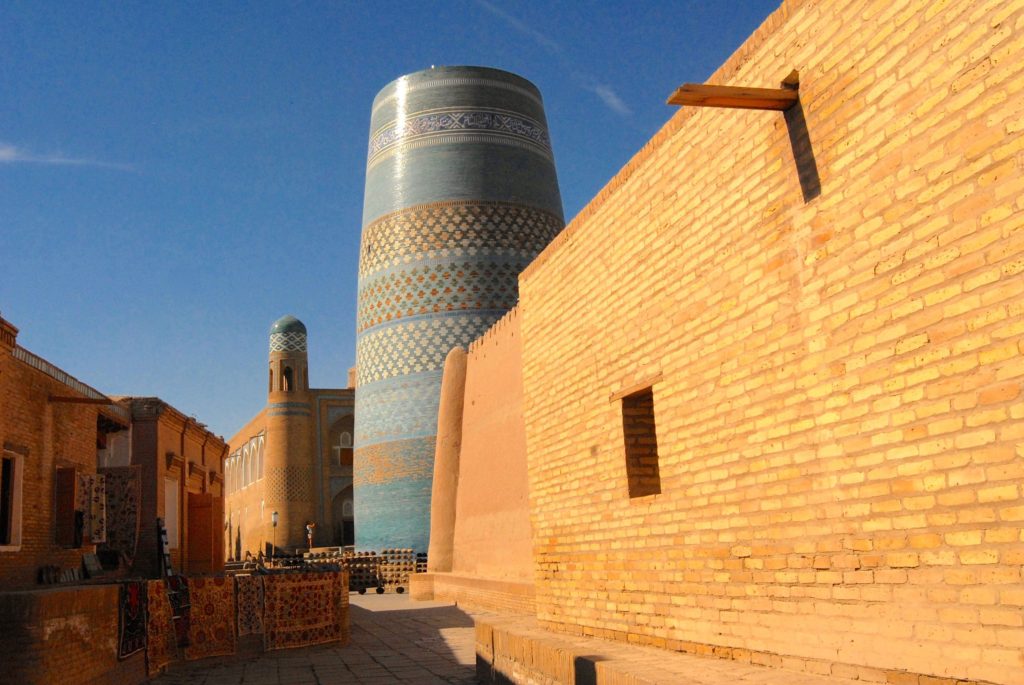

Kalta Minar

Fourteen minarets have survived in the centre of Khiva. They were constructed so that the muezzin might climb the stairs to call the faithful to prayer five times each day, his voice carrying on the breeze across the city.

Every postcard of Khiva seems to be illustrated with a photo of the Kalta Minar. This stumpy, but still eye-catching, green-and-turquoise landmark was intended to be the tallest minaret in central Asia: its patron, Muhammad Amin Khan, planned for it to be at least 70m tall, allegedly so that you could see Bukhara from the top. Sadly, it was not to be. Muhammad was murdered (page 263) before the minaret was complete and the architect responsible for the project fled.

Kyzylkum Desert

Named after its red sand, it is the world’s 15th-largest desert, and spreads across northern Uzbekistan and up into neighbouring Kazakhstan. Between March and May, and September and October, you can trek a circuit on foot or by camel from the village of Yangi Kazgan, just west of Lake Aidarkul; camel treks of two days or more include accommodation in the camel-hair yurts belonging to local Kazakh nomads.

Expect to enjoy the best of local hospitality, from homemade bread dipped in still-steaming camel milk, to hunks of camel meat. Beds are made up on the floor from piles of rainbow-coloured blankets and rugs, and you’ll often sleep cheek-by-jowl with other guests. You’ll never forget the experience, and certainly won’t get cold at night.

You can arrange camel trekking through a tour company or, alternatively, by approaching the camel camps directly. The first two camps to be opened, both inland from the west end of the lake near Kushkuduk and providing a high level of service, were Sputnik Camel Camp and the nearby Yangi Kazgan Yurt Camp.

A couple of newer options, located close to the lake at Eski Dungalok, are Aidar Yurt Camp and Qizilqum Safari, which have permanent yurts on concrete bases, good wash blocks, electricity and hot water; a local musician usually plays by a campfire (followed by a noisy party if there’s an Uzbek group staying – beware). The latest addition, on the south shore of the lake near Uchum, is Oxus Adventure Eco-Resort, which has wooden cabins as well as yurts.

In all of these cases you’ll pay about US$40 per person per day for accommodation, meals and a short camel ride (where you will be led, at least to begin with). The local Bactrian camels are far more comfortable to ride than Arabian dromedaries, although it’s all relative. Don’t expect to get too fond of your mount; camels are surprisingly hard creatures to love when you get up close and personal. Wet wipes will undoubtedly come in handy.

If you wander into the dunes around the camps you may see ground squirrels, skinks, hares and tortoises among the scrubby saxaul bushes, along with birds such as warblers, whitethroats, shrikes, sparrows, coveys of partridges, and with some luck the Turkestan ground-jay, and raptors such as snake-eagles and long-legged buzzards.

In spring and autumn, you may see migratory species such as demoiselle cranes, bustards and black vultures. It’s a short drive down to the lake (your camp will be able to take you), where over 100 species of waterbird can be seen, and there’s commercial fishing for species such as catfish, carp, snakehead and zander. There are also real beaches; walking along the shore is very pleasant, although some private resorts have been fenced off.

Poi Kalyon

The Poi Kalyon square is the star in the Bukharan sapphire, the beating heart of the Old Town, and the visual high point (both literal and metaphorical) of the city’s skyline. The name, which means ‘at the foot of the Great’, is derived from its place at the foot of the Kalyon Minar (the Great Minaret), the tapering, mud-brick tower which rises gracefully some 46m above the city.

Kalyon Minar

The minaret was built in 1127 and it was, so an inscription tells us, the work of an architect named Bako. He ordered that the foundations be dug some 13m deep, and demanded the labourers use a special mortar that was mixed with bulls’ blood, camel milk and eggs, which took two years to set. The exact original height of the minaret is unknown but it is thought to have been the tallest free-standing tower in the world. The uppermost section appears to have been lost (possibly due to an earthquake) and the part below reworked.

Bako died not long after the minaret was completed, purportedly broken hearted that it had failed to live up to his dreams. Genghis Khan looked upon it a little more favourably in the following century, however, and, having seen it for miles as he rode across the steppe and been suitably impressed, he spared the tower when all around it was razed.

It used to be possible to climb the 104 steps of the spiral stairs to the top, where the Mangits were fond of tying their prisoners up in sacks and chucking them off the top, a grisly but no doubt effective punishment that endured well into the 1800s (and again in 1917–20), much to the disgust of Lord Curzon. Now, however, there’s only access for researchers.

Kalyon Mosque

In the sundial-like shadow of the Kalyon Minar, the Kalyon Mosque stands on the foundations of the earlier, 8th-century mosque in which Genghis Khan ordered that the pages of the Qu’ran be trampled beneath the feet of his horses and the entirety of Bukhara (with the exception of the Kalyon Minar) be destroyed. The mosque was burnt to a cinder.

This replacement, a worthy successor, is also known as the Juma or Friday Mosque and was built by the Shaybanids in 1514. An inscription on the mosque’s façade attests to this completion date. Since then it has served as the city’s main mosque: there is space for more than 10,000 worshippers to pray, the entire male population of the city at the time of its construction.

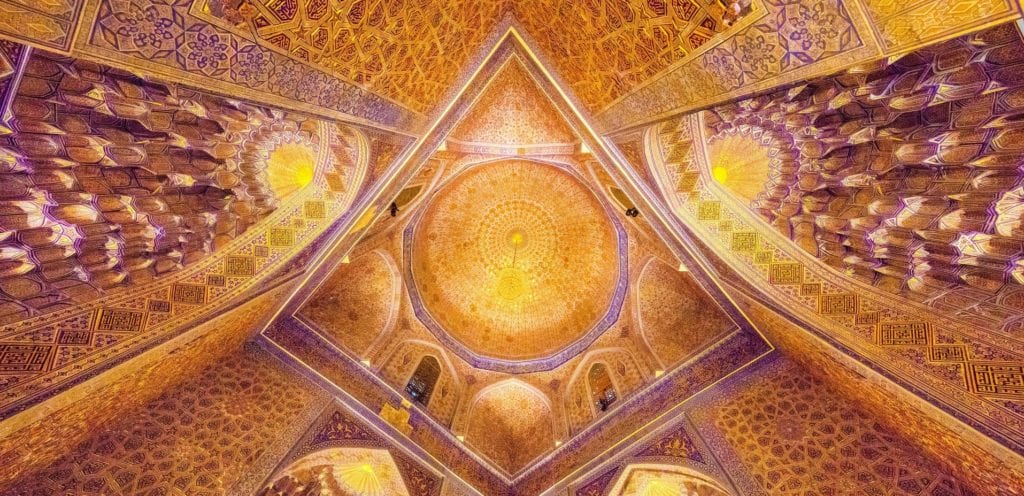

Passing through the eastern gate on Poi Kalyon, you enter a truly breathtakingly beautiful courtyard surrounded by 208 columns and 288 domes; the numerous pillars, forming triple aisles on either side, evoke the legendary court of Solomon and are an evocative statement in mosques and palaces from the Alhambra in Moorish Spain, to the forts and palaces of emperors in Mughal India.

At the far (western) end of the plaza is the turquoise- tiled Kok Gumbaz (blue dome), an architectural bubble, the shape of which belies its weight and width. Beneath it lies the mosque’s wonderfully gilded mihrab and an unusual octagonal structure designed to improve the building’s acoustics, amplifying the voice of the imam as he speaks his Friday sermon. The inscription on the dome itself, a spider-spun web of Kufic calligraphy, reads ‘Immortality belongs to God’.

Mir-i Arab Madrasa

Opposite the mosque is the Mir-i Arab Madrasa, constructed, so they say, with the profits from the sale of 3,000 Persian slaves. Its benefactor, the Shaybanid Khan Ubaidullah, clearly felt a need to salve his conscience, and hence in 1530–36 he endowed what is considered one of the most important educational establishments in the Islamic world.

With the exception of a 21-year period of closure from 1925 to 1946, it has remained fully functional, including throughout the Soviet period, and today around 120 students are studying here. They take a demanding four-year programme of Arabic and Qu’ranic studies, the first step on the path to becoming imams. There is limited access for tourists to the madrasa: you can enter the foyer and look into the inner courtyard but, theoretically at least, can go no further.

However, if you ask nicely and there is an appropriate guide present, you may also be permitted to view the tombs, under the left dome, of Sheikh Abdullah of Yemen (also known as Sayyid Abd Yamaniy or Mir-i Arab, the prince of the Arabs), a close friend of Khan Ubaidullah who directed the madrasa’s construction. The tombs are marked with a white flag and a goat’s tail, the traditional signs of saints, and of Khan Ubaidullah himself.

Samarkand

Buildings of breathtaking beauty in the heart of regal Samarkand have captured imaginations through the ages and will undoubtedly continue to do so. Medieval merchants must have marvelled at every sight, from the exotic goods on sale to the spectacular manmade backdrops of madrasas, mosques and mausoleums. Centuries on, visitors are still struck by the beauty, the number and the scale of Samarkand’s architectural sites, and are often moved by thoughts of the ambition, dedication and, no doubt, personal sacrifices required to turn dreams into concrete reality.

The Registan Square, with its three exquisite madrasas, is Samarkand’s biggest draw and makes for a picture-postcard scene. It’s far from the only attraction, however, as the ruins of Afrosiab, the observatory of Ulug Beg and the Shah-i Zinda, the necropolis of the Living King, are sights that you’ll never forget.

The time of year you visit Samarkand will have a significant impact on your experience: coming out of season, especially in the autumn months, will enable you to get close to the building’s physical details and to linger for as long as you like. The city always was a bustling, cosmopolitan place, however, so even if you are sucked into the summertime crowds, your experience will be no less authentic: the residents of Samarkand have for centuries made money from the foreigners passing through.

The Registan

Samarkand’s central square will make even the most architecture-weary visitor stand up and take note. Pausing for a minute (and a photo) on the raised viewing platform, the square unfolds below you. An almost infinite number of contrasting patterns swirl and dance on every surface but somehow never clash; the equally garishly patterned textiles worn by Uzbek women walking by appear almost as a continuation of the buildings themselves. The effect is completely mesmerising.

The Registan grew up around the tomb to the 9th-century saint Imam Muhammad ibn Djafar (the tomb can be found in front of the Sher Dor madrasa, but is barely noticeable nowadays), but by the 14th century this was also the commercial heart of the town. Six roads ran through the square, and it was connected directly with Timur’s citadel. Imperial decrees were shouted from the rooftops, and people would have gathered here to watch military pageants and other forms of spectacle.

Bibi Khanym Mosque

This is one of Samarkand’s most impressive sites, but also one of its most controversial owing to the heavy reconstruction that has taken place. It was built between 1399 and 1404, when it was the world’s largest mosque. It seems that the speed of the mosque’s original construction led to shoddy workmanship, and began to decay not long after completion.

What you see now is an almost total rebuild that started in 1974, as much of the original collapsed after an earthquake in 1897. Restoration is still underway, notably in the great western cupola, where huge earthquake cracks are still visible.

Shah-i Zinda

The Registan may be Samarkand’s poster child, but for many the real star of the show is the line of blue-and-turquoise-tiled tombs known as the Shah-i Zinda. The name Shah-i Zinda translates as ‘Living King’, referring to Samarkand’s patron saint, Kusam ibn Abbas, a cousin of the Prophet Muhammad who came here in 710 AD to preach Islam.

Legend has it he was beheaded by brigands while at prayer, picked up his head and jumped into a well where, so they say, he lives to this day. Regardless of whether he died or not, one of the mausoleums within the complex is dedicated to him: the Mausoleum of Kusam ibn Abbas.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Uzbekistan:

Related articles

Discover our favourite sights along one of the most important trading routes in history.

Get to know Uzbekistan before you travel there.

Exploring one of our favourite regions with our Photographer of the Month, Cynthia Bil.

Sit back and enjoy this kaleidoscope of colours.

Now you can see the Uzbek capital in a new light.

Among the most iconic sights on the Silk Road, this central square is one of the world’s greatest examples of medieval Islamic architecture

Beyond the striking mosques, mausoleums and madrasas, Uzbekistan has plenty more to offer

Most people go to Uzbekistan for its Silk Road treasures, but the real jewel in its crown is its people.