In a small area it seemed to contain everything I liked best about rural England: dramatic coastal scenery, lovely villages advertising cream teas, little churches full of ancient village art – and Exmoor ponies.

Hilary Bradt, author of Slow Travel Exmoor

‘We came to the great River Exe … which rises in the hills on this north side of the county … The country it rises in is called Exmoor. Camden calls it a filthy barren ground, and indeed, so it is; but as soon as the Exe comes off from the moors and hilly country and descends into the lower grounds, we found the alteration; for then we saw Devonshire in its other countenance, cultivated, populous and fruitful.’

– Daniel Defoe, 1724

This is still an accurate picture of Exmoor if you change ‘filthy barren ground’ for something more complimentary, for it is the heathercovered moorland as much as the cultivated, populous and fruitful lower ground that draws visitors.

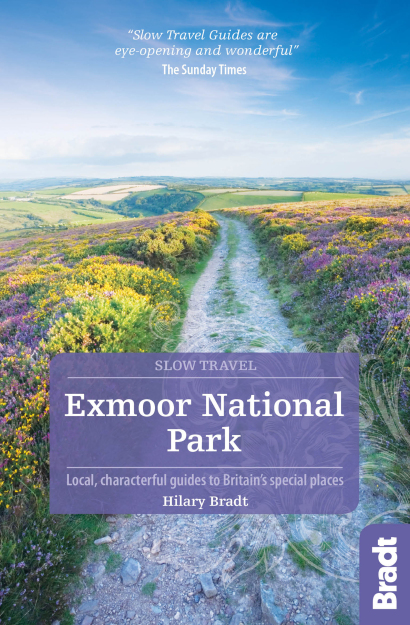

This is one of England’s smallest national parks, a soft landscape of rounded hills, splashed yellow from gorse and purple in the late summer when the heather blooms, and of deep, wooded valleys. And Exmoor has the coast, adding pebble coves and sea views to its attractions, along with the many rivers that race to the sea from the high ground, slicing into the soft sandstone.

With so much of Exmoor managed by the National Trust, clear signposting makes walking or cycling a real pleasure. Astonishingly, for such an utterly delightful region, it’s one of England’s least visited national parks. You may not believe this on a sunny weekend in Lynmouth or at The Hunter’s Inn when they’re buzzing with visitors, but solitude is not hard to find.

For more information, check out our guide to Exmoor

Bradt on Britain – going Slow in Exmoor National Park

It’s impossible not to go slow in Exmoor. From a practical point of view the lack of main-road access and narrow lanes discourage the vroom-vroom mentality, just as the lack of mobile-phone coverage discourages screen addiction. Moreover, the sheer delight of this heathery national park, where moor meets sea, means that visitors can’t help but take their time to absorb what they are seeing, talk to locals, indulge in a cream tea and realise that they are in one of the loveliest places in the country. And one which, somehow, has escaped mass tourism.

Of all the experiences I have encountered in this region, one stands out because it epitomises Exmoor. I had left scant time to do a newly discovered walk which I’d identified on the map as looking ideal in its combination of moor and coast, with one of my favourite churches, Trentishoe, thrown in and the hospitable Hunter’s Inn providing a base. It also looked short. It was a late September evening and I disregarded all my own advice, setting out without my hiking pole and boots. Which meant that I had to go slowly or risk an accident.

No problem – I needed to spend time enjoying the smell of bracken, the sunlight on the heather, and the sight of the Mediterranean-blue sea below sheer indented cliffs. And to stop to look at birds and views through my binoculars. I walked back to my car through an ancient bit of woodland proclaimed by the National Trust to be a ‘butterfly trail’, though it was now too late to observe insect life. Indeed, it was starting to get dark and I was due to meet friends at a time already past. And, this being Exmoor, there was, of course, no mobile-phone coverage. I asked the barmaid at the busy Hunter’s Inn if I could use their landline. No problem, no charge, just friendly helpfulness.

That’s Exmoor for you.

What to see and do in Exmoor National Park

Dulverton

Dulverton seems to have everything going for it: lovely surroundings, plenty to see and do, yet manages to avoid any suggeston of being a tourist hotspot. No wonder the national park chose to have its headquarters here.

Like so many places in Exmoor, Dulverton has its Lorna Doone association and there’s a small statue of the young woman outside Exmoor House. It’s actually of Lady Lorna Dugal ‘who, in the seventeenth century, was kidnapped in childhood by the outlaw Doones of Badgworthy’, so was probably the inspiration for the novel. The hero of the story, John Rudd (known as Jan when he was a boy) first sets eyes on Lorna as a little girl ‘dark-haired and very wonderful, with a wealthy softness on her’ as she sits in a handsome coach near Dulverton. Later, near Dunkery Beacon, he unknowingly sees her again, carried across the saddle of one of the Doone brigands, back to their hideout.

The town’s attractions include a 17th-century bridge over the River Barle, a variety of independent shops, some good restaurants and the excellent Heritage Centre. Shops include the greengrocer H&M (1 Fore St) with a colourful display of all manner of fruit and vegetables, and a farm shop opposite the Bridge Inn that sells fresh produce and snacks.

Art lovers old and young, or anyone searching for quality crafts, should take a look at Number Seven, which, as well as its cards, books and arty items, hosts the outstanding illustrator Jackie Morris and other artists. I particularly liked the ‘textile taxidermy’ by Helly Powell.

Also not to be missed is Tantivy, a super delicatessen and general store with a large selection of local beers and ciders, and a good range of maps and books as well as picnic supplies – so you’ll be all set to head for the moor. But not before you’ve visited The Guildhall Heritage and Arts Centre. Admission is free but donations are appreciated.

There are fixed and shifting exhibits here with lots of variety and surprises, like Granny Baker’s Kitchen where, at the touch of a button, the good lady will chat to you about her life and times. The red deer exhibit tells you everything you need to know about Exmoor’s iconic animal. In a separate building is a model railway, beautifully made and correct to the last detail. It’s Dulverton as it was before the railway was closed, and the little trains purr their way through tunnels and the familiar landscape before drawing to a halt at the station.

Each year Dulverton celebrates a Sunday festival, Dulverton by Starlight, in early December; the town is decorated, the shops stay open, there’s an evening fireworks display from the church tower, and other events are held to help get people into the Christmas spirit.

Dunster

Dunster sits just within the national park, and is deservedly the most visited small town in eastern Exmoor. It’s also one of the best-preserved medieval villages in England, with car-harassing narrow streets and the backdrop of a splendid castle and the folly-topped mound of Conygar Wood. Until 2011 the pavements comprised ancient cobblestones that looked lovely but made for painful and sometimes dangerous walking. Parts have now been replaced by paving slabs, which are less charming but easier on the feet.

The shops are tasteful, selling high-quality goods; the traffic is controlled; and there are lots of quality pubs, tea shops and snack bars. Among the shops is the excellent Deli, which sells a good selection of local crafts and a huge range of local beers and ciders.

It’s strange to think that in the 12th century Dunster Haven was a busy port. When the shore became land, the town switched its activities to the wool trade so successfully that the local cloth was known as ‘Dunsters’. The octagonal Yarn Market was built in 1609 to protect the wool traders from the Exmoor weather; it serves a similar purpose for damp tourists today.

Medieval towns like this often feel claustrophobic, but Dunster revels in open spaces and enclosed public gardens. Across one such space, the Village Garden, is the dovecot, which probably dates from the 14th century and still has the nest holes. It originally belonged to the priory but after the Dissolution of the Monasteries was sold to the Luttrells (the family that lived at Dunster Castle for 18 generations). Young pigeon, squab, was a luxury food, and until the 17th century only lords of the manor and parish priests were allowed to keep pigeons.

Near the dovecote is a lovely little church garden, and the red sandstone church of St George. First impressions are of a gloriously intricate wagon roof, some good bosses, and a font with a complicated cover. And the famous screen. Now, most old churches have screens, and many have screens as beautifully carved as this one, with fan vaulting to support the weight of the rood. But none, anywhere, has a screen this length, stretching across the full 54-foot width of the church.

A rural lane running alongside a stream leads to the Water Mill. Dating from the 17th century and grinding wheat daily to produce flour for its shop and local bakeries, it’s an interesting place to visit and the tea room serves very tasty light meals. Continue past the mill and you enter the spacious gardens of Dunster Castle.

This is the perfect approach to the castle: peaceful and uncrowded with, when I was there, only the sound of birdsong and the river. A path winds round to the main, steep entrance to the castle, which is also easily accessed from both West and High streets. Be warned, though; it is a very steep climb (Angina Hill, they call it) from the town or the castle car park so it’s not really suitable for visitors with health problems.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Exmoor National Park:

Related articles

Nothing found.