South Wales offers limitless opportunities for outdoor pursuits, be it trekking the mountains and tramping the coast path, mountain biking in the Valleys, riding cross country in the Black Mountains, or coasteering and kayaking the coastline.

Norm Longley, author of South Wales: the Bradt Guide

In many ways, South Wales is a microcosm of the country as a whole, embracing imperious red sandstone mountains, deeply incised valleys and a long, craggy coastline punctuated with enchanting coastal resorts and some of Europe’s finest beaches. Throw in a slew of theatrically sited castles and comely wayside villages – many with an ancient church – and it’s clear to see why this region packs a mighty punch.

Working your way east to west – arriving from England as it were – first stop is Monmouthshire, a verdant landscape of rolling countryside peppered with many an old Marcher fortress. A major stop on anyone’s list should be Cardiff, the nation’s vibrant, youthful capital, a city that’s almost unrecognisable from even just a couple of decades ago.

Extending like thick veins up towards the Brecon Beacons are the Valleys, once the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution and perhaps the most instantly recognisable landscape in all of Wales. Factor in some wonderful industrial heritage, outstanding hillwalking and mountain biking, and the Valleys deserve to be far more visited than they are. South of here, the Vale of Glamorgan is also all too often bypassed, but that would be to miss out on a lovely stretch of coastline richly textured by history and nature.

Carmarthenshire, too, remains something of an unknown quantity for many, but as home to some of Britain’s finest gardens and castles, it’s worthy of extended exploration. The highest-profile region in Wales is Pembrokeshire, in part because it possesses the most popular section of the entire Wales Coast Path but primarily because of its outstanding synthesis of stunning beaches and coves, and a multiplicity of endearing coastal resorts.

The Brecon Beacons is not far behind in the popularity stakes, its tangle of well-worn paths furrowed across four geographically distinct mountain ranges variously endowed with chiselled peaks, glacial lakes and waterfalls.

All of these areas offer limitless opportunities for outdoor pursuits, be it trekking the mountains and tramping the coast path, mountain biking in the Valleys, riding cross country in the Black Mountains, or coasteering and kayaking the coastline.

The Pembrokeshire Coast is on our list of 2023 Exceptional Trips! Read the full list here.

And check out this Wales road trip itinerary to plan your next trip.

For more information, check out our guide to South Wales

Food and drink in South Wales

Food

The Welsh culinary scene is almost unrecognisable from even just a decade ago, and it’s no longer the UK’s poor relation. Both the quality of the produce, much of which is now grown organically, and the types of places where you can sit down and tuck into great gastronomic fare have improved considerably.

With its rich valley pastures providing fine grazing, Welsh dairy products are superb. Welsh cheese is a serous rival to anything the French can muster, and while Caerphilly’s crumbly white cheese is the most well known, there are others, like Perl Wen (White Pearl) from Caws Cenarth, a soft creamy cheese not dissimilar to Brie, and Y Fenni, a spiky mustard-and-ale-infused cheddar from Abergavenny.

Similarly, this fertile land facilitates the cultivation of abundant fruit and vegetables. With its mild climate, Pembrokeshire’s early potatoes are rated the best in the land, closely followed by those from Gower – and where would we be without the venerable leek?

In a land packed with sheep, it’s little wonder that lamb is king, in particular saltmarsh lamb from Gower, which gains its unique flavour from the animal’s diet of sorrel, sea lavender and samphire. In a similar vein, Welsh Black beef also has superior flavour, as a result of the cattle – Wales’s only native breed – grazing at higher altitude.

With so much coastline, seafood – including bass, crab, mussels, lobster, sole and mackerel, among other wet treats – comes as standard on menus throughout the region, but of course particularly in Pembrokeshire. The Wye may not be the great salmon river of yore, but it’s still fished, as are the Tywi and Usk, both for salmon and sewin (trout), while cockles trawled from Penclawdd on North Gower also make their way on to many a menu.

There are a handful of wonderful Welsh delicacies which it’d be remiss not to try, among them cawl, which usually refers to any soup or broth but typically includes a meat of some kind, perhaps lamb or mutton. Described by the actor Richard Burton as ‘Welshman’s caviar’, laverbread, which is essentially seaweed, is something of an acquired taste; it’s a regular staple on most breakfast menus and must be tried at least once – who knows, you might even like it. In fact seaweed is increasingly being used in many recipes, from butter to brownies, not only because of its taste but also because of its extraordinary health-giving properties.

A great brunch option is Welsh rarebit, a bit like cheese on toast but here the cheese is mixed with beer, mustard and Worcester Sauce, while the legendary Glamorgan sausage, made from local cheese and spices, is so good that it is likely to appeal to carnivores too.

Drink

In recent years, the big breweries like Cardiff-based Brains have been usurped somewhat by the entrance of dozens of craft beer breweries into the market, which has certainly livened things up. From hoppy ales to fruity IPAs, imperial stouts to dark sours, it seems like there’s no end to the creativity.

Leading the way is the cool Tiny Rebel brewery based in Newport, who have also got three bars, but others to seek out include Llanelli-based Felinfoel – Wales’s oldest brewery (1878) and the first craft brewery in the world to supply beer in a can (1935), though that’s no surprise since Llanelli is home to a tinplate works – Tomos Watkin in Swansea, Evan Evans in Llandeilo, Pipes in Pontcanna, Cardiff, and Tenby Brewing.

Although there is evidence of there being whisky stills in Wales as far back as the 4th century, when the Penderyn distillery started doing so in 2000, it was the first to do so in Wales for more than 100 years. The only other whisky producer in South Wales is the Coles distillery in Llanddarog, Carmarthenshire.

Penderyn also distils vodka and gin, and as seems to be the vogue, specialised gin distillers are springing up all over the place. A couple of interesting ones are the Silver Circle distillery in Catbrook, the Wye Valley, and Hensol Castle distillery just outside Cardiff. To many people’s surprise, South Wales is a fertile wine producing area, with both the soil and climate here offering ideal growing conditions. Two excellent outfits are Llanerch in the Vale of Glamorgan and White Castle in Monmouthshire.

The artisan coffee boom has well and truly hit South Wales and shows no sign of abating. Inevitably Cardiff has the most interesting scene and coffee is brewed with obsessive care, but even in the smaller towns, there should be at least one independent coffee shop doing something interesting. The dominant roaster on the market right now is Coaltown Coffee Roasters in Ammanford.

Health and safety in South Wales

Health

Overall, there’s nothing to be overly concerned about in terms of health when travelling in South Wales. The biggest health risks are likely to be when enjoying the great outdoors, but by taking sensible (often obvious) precautions, for example applying suncream if you’re out walking and it’s hot, you can mitigate against most potential problems.

If you are planning on doing any walking – particularly in wooded areas or long grass during spring and summer – one potential hazard to look for is ticks, parasitic arachnids that embed their heads in the skin and suck on your blood (it’s not quite as vampirish as it sounds). You can reduce the risk of a bite by wearing lightly shaded, tightly woven clothing, in addition to applying a permethrin-based repellent.

The major A&E hospitals in South Wales are Glangwili in Carmarthen, Morriston in Swansea, the Prince Charles hospital in Merthyr, the Princess of Wales hospital in Bridgend, the Royal Glamorgan in Llantrisant, the Grange University Hospital in Cwmbran, Withybush General in Haverfordwest, and the University Hospital in Cardiff. These are complemented by Minor Injuries Units all across the region.

Safety

Wales is an extremely safe place to travel, though the usual precautions apply when in some of the bigger cities, especially at night. The biggest risk to one’s safety, ironically, is the great outdoors. If, as is likely, you’ll be doing some walking here in South Wales, then be wary of cattle. Don’t come between a calf and its mother, be a little more circumspect in May when the beasts have just been released from being cooped up indoors for months and always keep your dog on a lead when there are cows about.

Walking the coast path, stay away from cliff edges, however tempting it may be to peer over – that said, where there has been rockfall or slips, places are usually fenced off pretty quickly. Beaches of course present their own dangers. Many beaches in South Wales have lifeguards in the peak summer months, but as many of them are so vast, they are often only able to patrol one section, or zone, which is usually denoted by flags. Be aware of potential rip tides and currents too.

Travelling with a disability

Much work has been, and continues to be, done in Wales in terms of providing facilities for travellers with disabilities. While older hotels have limited facilities and access, the majority of accommodation providers (even hostels) have at least one accessible room available, with ramps and fully accessible wet rooms.

As transport facilities get upgraded, such as new electric buses, access is becoming increasingly standardised. If travelling with a wheelchair by train, advanced warning will enable station staff to prepare ramps at the appropriate station. Traveline Cymru has comprehensive details on access and facilities on its website, while another useful resource is the National Rail website.

Many visitor attractions are now fully wheelchair-accessible (certainly most museums), although inevitably there are some buildings whose configurations simply don’t lend themselves to decent access, most obviously some (but by no means all) of the region’s castles. Visit Wales has a list of some of the accessible accommodation and attractions in South Wales, though this is by no means comprehensive. Another useful website is the RNIB.

LGBTQ+ travellers

During the 1984 miners’ strike, miners received support from an unlikely source, namely the lesbian and gay community, although they weren’t from Wales but from London – manifestations of gay life in Wales were virtually non-existent at that time. Establishing themselves as the Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) group, by the end of the strike nearly a year later, 11 different lesbian and gay alliances from across the UK had emerged in support of the miners, and together had donated more money to their cause than any other fundraiser.

These events, and the subsequent relationships that developed between the miners and the gay community were the subject of the fabulously entertaining film, Pride, in 2014.

Things have moved on a bit since those dark days, although manifestations of gay life beyond Cardiff and Swansea are still conspicuous by their absence. Cardiff’s Pride event takes place at the end of August, but otherwise there are a few bars and clubs in the city, as well as an excellent shop, Queer Emporium, in the Royal Arcade.

Travel and visas in South Wales

Visas

Citizens of all European countries – other than Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and most republics from the former Soviet Union – can enter the South Wales (and the rest of the UK) with just a passport for up to three months. US, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand citizens can travel in the UK for up to six months with a passport. All other nations require a visa, available from the British consular office in the country of application.

Now that the UK has left the EU, visa regulations are subject to change, so contact the nearest British embassy or high commission before travelling. Once in Wales you are free to travel into England or Scotland. Check gov.uk/browse/visas-immigration.

Getting there and away

By coach

Coaches ply the M4 corridor, with both National Express and Megabus operating services from London to Cardiff. Buses are roughly every 90 minutes with a journey time of around 3 hours 45 minutes. Fares can vary massively (with both companies), but book far enough in advance and you could secure a ticket for as little as £5 one-way.

National Express also operate a handful of buses each day from London to Swansea, via Cardiff and Bridgend, with a journey time of around 5 hours; and from London to Pembroke Dock, calling at Swansea, Carmarthen and Tenby among other places.

By air

The likelihood of you arriving in South Wales by air are slim, given that there is only one airport, Cardiff (in Rhoose, to the west of the city), and even they it is serviced by very few flights. It may well be that both Ryanair and Wizz Air both of whom currently fly to a limited number of destinations from Cardiff, increase the number of flights they offer.

In 2021, Ryanair started flying from Cardiff to Dublin, and in 2022 Wizz Air announced that they were to make Cardiff their fourth UK base.

By sea

There are two entry points into South Wales by sea, both of which originate in Rosslare, southwest Ireland. From Fishguard, in western Pembrokeshire, Stena operate two daily ferries to Rosslare, with a crossing time of 3 hours and 30 minutes or 4 hours.

Irish Ferries also operate two ferries a day to Rosslare, but from Pembroke Dock on the southern Pembrokeshire coast. This crossing takes marginally longer at 4 hours (return fare from around £78 adult, £270 car).

By rail

The most straightforward entry into South Wales by train is the London Paddington line to Cardiff, which also stops at Newport. Trains from Paddington also service Swansea, stopping at Bridgend, Port Talbot and Neath en route. Trains run every 30 minutes to Cardiff and hourly to Swansea.

A far more agreeable way of reaching South Wales by train is via the Heart of Wales line, which is operated by Transport for Wales. The line starts in Shrewsbury, northeast of Birmingham, and enters Wales at Knighton before wending its way down through mid-Wales to Llandovery, Llandeilo, Ammanford, Llanelli and finally Swansea (with a zillion stops in between).

Getting around

By car

Welsh roads are, for the most part, excellent. With regard to South Wales, the principal entry points from England are the M4 and M48 motorways, the former originating in London and ending in eastern Carmarthenshire, the latter a short 13-mile stretch of road which veers off the M4 in England before crossing the Severn Bridge near Chepstow and rejoining the M4 near Newport.

Driving in southeastern Wales can be frustrating, particularly around Newport and Cardiff, but apart from that, congestion is not a huge issue. Your biggest frustration in the Brecon Beacons is likely to be sheep rather than other vehicles. though even they somehow manage to take the stress out of driving.

By bus

The bus network is generally excellent, with local services run by a bewildering array of companies, though nearly all operate a much-reduced service on Sundays, if they run at all. Moreover, such are the relatively short distances between places in South Wales that no one journey is ever particularly arduous.

Traws Cymru operate half a dozen or so medium-to-long-distance services throughout Wales. Of relevance to South Wales are T1 (Carmarthen to Aberystwyth), T4 (Cardiff to Newtown in Powys, via Merthyr and Brecon), T5 (Haverfordwest to Fishguard), T6 (Brecon to Swansea), T11 (Haverfordwest to Fishguard via St Davids) and T14 (Cardiff to Hay-on-Wye via Brecon). These buses are clean, comfortable and have Wi-Fi – and do have Sunday services.

By train

Like buses, the train network in South Wales is generally excellent, if not quite as far-reaching, which is not surprising given the terrain. The main inter-city line is the one from London Paddington whose first stop in Wales is Newport, then Cardiff, Bridgend, Port Talbot, Neath and Swansea. From these stations, suburban and rural services fan out into Monmouthshire, across the Valleys and the Vale of Glamorgan, and, from Swansea and Carmarthen, into Pembrokeshire.

When to visit South Wales

If you’re here to walk, then where in South Wales you want to walk is likely to influence when you come. If you’re walking the coast path, then summer is clearly the best time in terms of weather, but you will be reckoning on loads of other people doing the same, and it can get murderously busy, particularly on the more popular sections of the path like Pembrokeshire – notwithstanding the fact that it’ll be much harder to find accommodation during this period.

For this reason the best time to tackle the coast path is late spring (April/May), not only because of the thinner crowds but also because of the profusion of flora, with wildflowers coming into bloom across the clifftops. You may also see dolphins and other cetaceans gambolling off the Pembrokeshire coast.

September, too, can be a lovely time; the crowds have largely dispersed and the weather is probably at its most reliable, though most of the birds have gone by this stage. The great thing about the coast path of course is that in theory you can walk it any time of the year, so if you’re feeling particularly hardy – and don’t mind the biting winds – then winter is always an option.

The Brecon Beacons is a slightly different proposition: winter and early spring are almost certainly out of the equation, with snow often remaining on higher ground until well into March. Therefore, late spring and early summer is the optimum time to walk, though the weather can change drastically at any time so thorough preparation is paramount; the Brecon Beacons are very exposed, so heat can be just as much of a factor.

As for inland South Wales, again late spring and early summer (before the school holidays) is a good time, as the weather is at its most reliable and everything is open. The Valleys are not exactly a tourist hotspot, so go any time of year and you’ll pretty much have the run of the place.

If you’re here specifically to see wildlife, late spring and early summer is the best time. Puffins, for example, start to arrive on Skomer in late March/early April, along with most of the migrant fauna (guillemots, razorbills, Manx shearwater).September/October is prime pupping time for the colonies of Atlantic grey seals.

Public holidays and festivals

In early March, you can start shedding a few of those winter calories attending the superb Crickhowell Walking Festival, nine days of exhilarating treks around the Brecon Beacons, alongside talks and other events. At the end of the month, the focus switches to Laugharne and all things Dylan Thomas courtesy of the Laugharne Weekend, three days of readings, film and music.

Towards the end of May, the behemoth that is the Hay Literary Festival rolls into this small town, or more accurately an enormous field just outside town. Attended by the most celebrated names in the industry as well as actors, comedians and musicians, this ten-day gathering seems to get bigger every year.

In July, Caerphilly’s famous cheese is celebrated in all its crumbly glory in the rollicking Big Cheese Festival up at the castle, featuring historical re-enactments, a monster tug-of-war, and more cheese than you can shake a cocktail stick at.

August and it’s time for Green Man, whose setting in the heart of the Black Mountains, combined with a consistently first-class line up, as well as a strong focus on art and science, ranks it among the favourites on the British festival circuit. Tickets are invariably snapped up within days of going on sale.

The big one in September is the Abergavenny Food Festival, usually around the third weekend in September. One of Europe’s premier gastronomic events, it’s attended by a who’s who of culinary greats, with talks, tastings, masterclasses and much more in venues including the Victorian market hall and castle grounds.

Nothing in South Wales – or anywhere in Wales come to think of it – compares to Porthcawl’s Elvis Fest, the largest festival in the world (how many are there?) dedicated to ‘The King’. Some 30,000 ‘Elvies’ descend on this small seaside resort for a riotous weekend of singing and strutting, with official shows staged at the town’s Grand Pavilion. It really is a sight to behold.

Founded by prominent Welsh DJ Huw Stephens, the Swn Festival is Cardiff ’s big annual music hoedown; there’s no specific date but it usually takes place in early/mid autumn, its raison d’être to showcase emerging acts across multiple city-centre venues, but mostly those in and around Womanby Street like Clwb Ifor Bach.

What to see and do in South Wales

Blaenavon

Huddled under rolling moorland, Blaenavon is the archetypal Welsh mining streetscape of ruler-straight stone or rendered terraces of two-up, two-down houses.

True, it can be bleak here when the wind and rain come off the Brecon Beacons, and walking around, there’s an oddly melancholic air about the place, something that’s apparent in its tatty shop frontages and boarded-up pubs. But Blaenavon’s doughty community spirit remains intact and you’ll be greeted warmly.

During the 19th century, Blaenavon was pre-eminent among the world’s coal and iron-ore producers, and for this, the town and surrounding landscape was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 2000, the second in Wales and currently one of just four in total in the country.

Today this legacy is brilliantly brought to bear in a brace of heavyweight attractions: the enduringly popular Big Pit, and the awesome Blaenavon ironworks – add the Pontypool and Blaenavon steam railway into the mix and there’s more than enough here to warrant a full day’s exploration.

What to see and do in Blaenavon

Blaenavon Heritage Centre

The logical place to start is the Blaenavon Heritage Centre, which rates its own little nugget of history, for this is the oldest surviving works’ school building in Wales, built in three phases between 1816 and 1860. Interestingly, when it opened there were 120 children on the roll, a much lower number than those actually working the pits and ironworks.

In the adjacent grounds, the parish church of St Peter is worth a peek for its collection of cast-iron tomb covers and pillars – even the font is made from iron. It was built by the town’s ironmasters Hill and Hopkins, both of whom are buried here in iron-topped tombs, and consecrated in 1805 – if it’s not open, you can get the key from the heritage centre.

Big Pit

With its towering steel headframe standing sentinel, Big Pit is not only one of South Wales’s most popular visitor attractions, but it’s also the Valleys’ most authentic mining experience. Moreover, tours are led by ex-colliery personnel who entertainingly convey the hardships of life underground.

Although parts of Big Pit technically date to the early 19th century, it was opened officially in 1860, before being sunk to its present depth of 300ft in 1880. Kitted out with helmet, lamp and battery pack, visitors are lowered to a depth of 300ft in the original cages, before the walk along a labyrinthine web of tunnels to the old coal face.

Back above ground, you can make a bit more sense of what you’ve just experienced in a couple of exhibitions, one an audio-visual presentation entitled King Coal: The Mining Experience, and another in the old pithead baths. Constructed in 1939 and one of around 400 built throughout Britain during the inter-war period, the baths had heated lockers, and also incorporated a canteen, medical rooms and laundry.

Blaenavon Ironworks

Blaenavon’s magnificent ironworks is one of the most complete sites of its kind anywhere in the world, yet it wasn’t so long ago (the 1970s) that they were slated for demolition, before being taken into the care of the state. Established in 1788 under the partnership of Thomas Hopkins, Benjamin Pratt and Thomas Hill, the enterprise was set up with astonishing rapidity.

The site’s dominant structure, and its finest architectural specimen, is the hulking balance tower where water diverted from a stream was used to lift raw materials from the yard below on to tramlines and thence the Brecknock and Abergavenny canal. You can walk to the top of the tower via a looped path, from where there’s a superb bird’s-eye view of the site.

Opposite the cast house is Stack Square, another of the site’s original 1788 buildings and comprising Middle Row and Engine Row. A rare example of early iron company housing, these tiny limewashed cottages would have originally been home to specialist workers brought here to set up the ironworks, before being converted into more humble dwellings for lower-paid labourers.

Pontypool and Blaenavon Steam Railway

Just under 2 miles northwest of the town centre on the A4248 road between Blaenavon and Brynmawr, a signpost invites railway enthusiasts to the Pontypool and Blaenavon Steam Railway, and while there may be more scenic heritage rides in Wales, this is still an enjoyable little outing.

Built by the Brynmawr and Blaenavon Railway in 1866 before it was leased to the London and North Western Railway in 1869, the line operated as the main line for Big Pit until 1980, before its reincarnation just three years later as a heritage railway. For the best views, sit on the right-hand side heading out to the Whistle Inn halt, and on the left-hand side going in the other direction. Reckon on about an hour for the entire trip.

Brecon Beacons

South Wales’s Brecon Beacons is walking country par excellence – there are some 163 peaks here – and although in parts as popular as Snowdonia, is still large enough that you can find your own little corner. For the more adventurous, or those with some time, the 100-mile Beacons Way presents the ultimate challenge.

The park ranks the twin peaks of Pen-y-Fan and Corn Du as its highest – and by extension the loftiest in southern Britain. Both are eminently doable for anyone with a reasonable level of fitness, but during summer walkers home in on these two summits in big numbers, so you may want to divert elsewhere.

The western Beacons

Bleaker and wilder than any other area of the Brecon Beacons, the untamed western Beacons can be classified as having two distinct parts, namely the Black Mountain, not to be confused with the easterly Black Mountains (ie: plural) range, and Fforest Fawr, roughly somewhere between the Black Mountain and the central Beacons.

Few visitors take to the higher, more hostile interior of the western Beacons, preferring instead to stick to the beauty spots and attractions clustered in and around the southern fringes, like the Mellte and Pontneddfechan waterfalls and the caves at Dan-yr-Ogof.

Black Mountain

Contrary to its name, the Black Mountain (Mynydd Du) is not a singular peak but instead the name given to an area of mountains roughly spread between Ammanford in the southwest and Sennybridge in the north.

The Black Mountain’s inaccessibility means that it receives relatively few visitors, certainly compared with much of the rest of the Brecon Beacons, and therein lies much of its appeal. This elusive, untamed mountainous area also provides some of the most challenging walks in the national park, as well as some exceptional bike rides and drives, but whichever your preferred mode of transport, you’ll barely meet another soul here.

Fforest Fawr

A member of the European Geoparks Network and the UNESCO Global Network since 2005, Fforest Fawr translates as ‘Great Forest’, which is actually a bit of a misnomer because there’s hardly any forest here at all. Instead, this 300-square-mile area of moorland between the Black Mountain and the central Beacons takes its name from when it was used as a royal hunting ground.

One of just two geoparks in Wales, and eight in total in the UK, Fforest Fawr is a landscape some 500 million years in the making, from the Ordovician and Silurian rocks, the oldest, through to the red sandstone of the Devonian (400 million years) and Carboniferous limestone (350 million years) rocks, which are the two main materials that comprise this immediate landscape.

The Central Beacons

Slightly confusingly, the central Brecon Beacons is the area after which the whole national park is named. Although not approaching the heights of much of Snowdonia, the terrain here is still unmistakeably mountainous, comprising great walls of the same red sandstone that characterises much of the national park and sharp peaks that rise abruptly from the glacially carved landscape.

This is prime Beacons walking territory, and of all the areas within the park, the one where you’re likely to meet the greatest number of fellow walkers, most of whom are targeting the twin peaks of Pen-y-Fan (2,907ft) and Corn Du (2,863ft), South Wales’s – in fact southern Britain’s – two highest mountains.

These summits lie almost immediately due south of Brecon, a very likeable small town with a coterie of interesting sites, as well as excellent accommodation and dining, hence why many people choose to use this as the place to base themselves if they’re intending to spend any length of time in these mountains.

The Beacons Way

Inaugurated in 2005, but revised and extended in 2016, the Beacons Way is a stamina-sapping 100-mile linear walk through the park. It’s not just the length that makes this a real challenge, but the variety of terrain, from tough climbs and undulating ridges to peat bogs – and that’s before you’ve even started to factor in the weather.

Starting in Abergavenny, the trail meanders east–west to Llangadog, and some of the highlights en route include Skirrid, Llanthony Abbey, Crickhowell, Partishow Church, Table Mountain, Pen-y- Fan and Carreg Cennen. The website maps the route in eight stages (days), including what to see and accommodation options along the way.

Cardiff

One of Europe’s youngest and most dynamic cities, Cardiff is unrecognisable from the Welsh city of 20 years ago, having reinvented itself in a way few other capitals have managed, or dared, to do in the intervening period.

It was the opening of the Millennium (now Principality) Stadium in time for the 1999 Rugby World Cup that ushered in a monumental rebuilding programme for the city, which centred on Cardiff Bay, once a byword for squalor and decay.

The stimulus for the bay’s metamorphosis into a bona fide visitor attraction was a new barrage, alongside which new and now iconic buildings were raised, such as the Wales Millennium Centre and the Senedd.

Find unusual things to do in Cardiff here.

What to see and do in Cardiff

Cardiff Castle

Tucked into the southeastern corner of Bute Park and hemmed in by two of the city’s busiest roads, the spacious grounds of Cardiff Castle make for some welcome relief from all the outside noise. A Gothic Victorian fantasy of the most ostentatious kind, the main castle building as you see it today was the work of the coal-rich Third Marquess of Bute and maverick architect William Burges.

Within the castle it’s possible to view a selection of rooms on a self-guided tour but you’ll get to see more areas if you take a guided tour, for which there is a small additional fee.

The most impressive rooms are the church-like Banqueting Hall, featuring a gloriously kitsch chimneypiece, the well-stocked library, complete with Burges’s original bookcases and tables, and another superb fireplace, above which are carvings signifying the five ancient languages: Greek, Hebrew, Assyrian, Hieroglyphics and Runic.

National Museum

More compact and restrained than neighbouring City Hall, the National Museum was inaugurated in 1927 by King George V, a statue of whom stands opposite. The museum is a two-parter: the Evolution of Wales Gallery on the ground floor is a whistle-stop tour through the geology of the nation, though, oddly, much of what is on show comes from other continents, even the moon; a chunk of basaltic rock from the 1969 Apollo moon landing has somehow found its way to Cardiff.

The museum’s strongest suit is its art collection. Though by no means as vast as national collections found elsewhere in Britain, its coverage of Welsh art is unrivalled, while it also includes a clutch of exquisite Old Masters and some superb Impressionist works.

Cathays Park and the Civic Centre

Beyond the grand ceremonial avenue that is Boulevard de Nantes (named after the city twinned with Cardiff), Cathays Park is an area of neatly proportioned Edwardian buildings. Together these comprise the Civic Centre, front and centre of which is City Hall, an Edwardian-Baroque extravagance dating from 1906.

The hall is actually the fifth building in Cardiff to have served as the seat of local government, though none of the previous four town halls survive. The building is usually open to the general public during office hours, so if you’ve got a few minutes to spare, it’s worth having a nose around those areas that are accessible.

Principality Stadium

When it opened in 1999 just in time for the Rugby World Cup, the Millennium Stadium, as it was then known, was widely acknowledged as one of the most state-of-the-art stadiums in the world, and while it may have been superseded by other stadiums in the intervening 20 or so years, it remains a brilliant architectural achievement and one of the most atmospheric stadiums in world sport.

If you can’t get tickets for a match at the Principality (and you probably won’t), then the next best thing is a stadium tour, which takes in the changing rooms, pressroom, hospitality boxes and then a walk down the players’ tunnel to pitchside. Either way, there’s not much that beats Cardiff on match day, especially when hordes of beer-guzzling Scots or Irish roll into town swelling the already packed pubs and bars to bursting point.

Bute Park

Extending north from Castle Street up to Blackweir Woods, with the River Taff bordering one side and the A470 the other, Bute Park is one of Cardiff’s greatest assets. You could quite easily spend a day exploring its outstanding collection of trees, ancient ruins and modern sculptures, or simply ambling alongside the riverbank.

Bute Park is home to more than 3,000 catalogued trees, among them 41 Champion Trees (those deemed to be the tallest or broadest examples of their kind within Britain), a number unrivalled among municipal parks in Britain and Ireland.

Among the most important species here are Siberian Elm and Chinese Ginkgo Biloba, and if you want to seek them out, there are two Champion Tree trails (north and south), in addition to another trail mapping out a dozen or so of the park’s signature species.

Cardiff Bay

Wales Millennium Centre

An architectural triumph of the first order, the monumental Wales Millennium Centre is a suitably fitting home for the Welsh National Opera. Constructed solely from native Welsh materials, its most impressive aspect is the sweeping copper portico emblazoned with words composed by Wales’s first national poet Gwyneth Lewis: ‘In these stones horizons sing’, and ‘Creu gwir fel gwydr o ffwrnais awen’, the Welsh translating as ‘Creating truth, like glass, from the furnace of inspiration.’

The interior is just as dramatic: steel-clad walls, timber-lined stairs and polished wooden balconies. The main auditorium, the Donald Gordon Theatre, is a stunning space boasting sensuous curves, superb acoustics and perfect sightlines. Even if you aren’t here for a performance, do have a nose around.

Pierhead

No other building in the bay embodies better the wealth of the once all-powerful coal industry than the splendid neo-Gothic terracotta red-brick Pierhead. The one constant amid the flush of modern architecture, the Pierhead (1897) was commissioned by the Third Marquess of Bute and designed by William Frame to replace the Bute Dock Company offices that had burnt down five years earlier.

The interior is a riot of ornate plasterwork, walnut panelling and glazed tiles decorated with images of birds and fish, a theme its architect, Lord Bute, returned to time and again – as you’ll have seen if you’ve visited Cardiff Castle. Three rooms have been given over to an exhibition on the history of the building, the docks, and the neighbouring Senedd which owns the Pierhead.

Senedd

The main anchor among all this waterside development is the stunning Senedd, designed by Sir Richard Rogers as a permanent home for the Welsh Assembly, now called the Welsh Parliament. Looking as fresh and modern as it did when it was inaugurated in 2006, it’s an adventurous, beautifully executed building that, like the Millennium Centre, makes astute use of native materials.

Two of the building’s three levels are open to the public who are welcome to watch over a plenary session in the circular debating chamber, which was deliberately designed that way to advocate a more consensual style of politics – it’s worth noting then that Wales is one of the few countries in the world where women are in the majority in the cabinet.

Chepstow

One of the most anglicised of all Welsh towns, Chepstow (Cas-Gwent in Welsh, meaning ‘Castle of Gwent’) sits in a hairpin bend of the River Wye – in fact, its Norman name was Striguil, likely taken from the Welsh word ‘ystraigyl’ meaning ‘bend in the river’, before it appropriated the English version from the words ‘ceap’, meaning market and ‘stowe’ meaning place.

Notwithstanding some clumsy modern development, Chepstow is a place of not inconsiderable charm, thanks to its neat medieval layout and a colourful medley of whitewashed cottages and Georgian townhouses spilling down the hill towards the castle.

The castle is without doubt the town’s big draw, and alone makes Chepstow worth a diversion, though there’s plenty more to stick around for – and if you’re tackling one of the three long-distance trails that start (or finish) here, you could do worse than stay overnight and have a gander before setting off.

What to see and do in Chepstow

Chepstow Castle

Perched high above the cliffs, its sides dropping almost sheer into the muddy waters of the River Wye, Chepstow Castle was described by the late, great Jan Morris as ‘like a huge fist of rock at the very gate of Wales’ – and there’s no question it’s a mightily impressive sight.

It also stakes claim to being the oldest surviving stone-built castle in Wales – not a bad boast considering that there are over 100 castles still standing in the country. The Domesday Book records that the first stones were laid here in 1067 by William Fitz Osbern.

It makes sense, chronologically at least, to start in the Great Tower, the oldest, and only Norman-built, part of the castle. A vast rectangular hall-like space measuring over 130ft long, it would have originally had an upper and lower floor, as the pair of sawn-off arches – hewn from Purbeck marble and still bearing some beautifully crafted mouldings – would indicate.

The Great Tower aside, the most rewarding part of the castle is the suite of buildings dispersed around the Lower Bailey. Prominent here is the domestic range, comprising the roofless great hall, the heavily restored and minimally refurnished Earl’s Chamber, the kitchen and service passage, and a dank cellar possessed of a finely vaulted ceiling and a window through which wine and barrels of ale would be winched up from the river directly below.

Chepstow Museum

Directly opposite the castle car park, in a handsome cream-coloured Georgian mansion, the Chepstow Museum is a minor delight. Through a series of packed rooms, it recalls the history of the town, with emphasis on the trades that sustained it, including shipbuilding along the Wye.

There’s also reference to the time when the building, unlikely as it seems, functioned as a Red Cross Hospital during World War I and then as a district hospital. Upstairs is a particularly fine series of topographical prints of Chepstow Castle.

Old Wye Bridge

It’s surprising how few people make it to Chepstow’s town centre, most content to push on elsewhere after visiting the castle. This is a shame because there’s enough to warrant a couple of hours’ exploration, starting with the Old Wye Bridge, an elegant, cast-iron specimen built in 1816 by the splendidly named John Urpeth Rastrick, a renowned railway engineer.

Costing around £17,850 (about £1.2 million in today’s money), the five-arch bridge actually replaced a 500-year-old wooden structure. A cluster of plaques on the wall by the bridge relay all manner of fascinating facts and figures about both the bridge and the river: one contends that of all the iron arch road bridges built before 1830, this is the only one remaining.

St Mary’s Church

Heading back up Bridge Street, you’ll come to St Mary’s Church at the end of Upper Church Street. As with the castle, the church was founded by William Fitz Osbern in 1072, just a few years after the former, as a Benedictine priory. Beyond the superb Norman doorway, with its zig-zag and lozenge-style stonework, the church interior is a relative mish-mash of styles.

Now very much ageing, and in parts crumbling, a number of structural issues currently plague the building and there have even been threats of closure, so its future remains uncertain.

Gower

The first area in Britain to be designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1956, Gower is deserving of all the superlatives that frequently come its way.

In fact, to quote a few visitors to South Wales it eclipses many of Pembrokeshire’s finest spots. Gower has been inhabited since Paleolithic times, as the much-vaunted discovery of a skeleton at Goat’s Hole Cave in 1823 indicated, but evidence points to many other periods of human habitation here: a chambered tomb at Parc le Breos, an Iron-Age hillfort at Rhossili, and a Roman villa at Oystermouth.

South Gower

Originally settled by the Normans, wind-bitten south Gower is the most built-up part of the peninsula – and notwithstanding the odd bit of bungalow blight – is possessed of a string of fabulous blue flag beaches backdropped by sometimes sheer cliffs.

Many of the smaller coves and beaches here can’t be reached by car, so if it’s a bit of solitude you’re after, these are the ones to target. Three Cliffs Bay is the main one, but the likes of Oxwich Bay (home to one of Wales’s few Michelin-starred restaurants) and Port Eynon are just as rewarding.

Mumbles

On the edge of Gower, and effectively a suburb of Swansea, Mumbles is charm personified and a good place to stock up on provisions, especially if you’re planning to hunker down for a few days out west. Despite elements of gentrification, Mumbles has retained its Edwardian earthiness and is devoid of any of the tackier elements of your average seaside resort.

In fact Mumbles is one of those places where really you don’t need to do very much at all, except promenade, eat and drink. In recent years Mumbles has forged quite a reputation as bit of a foodie destination, and while places do come and go, you can expect to gorge well here. There are plenty of pubs too – it isn’t dubbed the ‘Mumbles Mile’ for nothing.

Oxwich Bay

Somehow the beaches seem to get better the further west you go, and so it is with Oxwich Bay just around the headland from Three Cliffs Bay, which is accessible by foot at low tide.

A three-mile sweep of soft pale sand, with safe, shallow sea, good surf and acres of space, this pretty much has everything you could wish for in a beach. It’s also ecologically sound thanks to its status as a national nature reserve, Oxwich Burrows, which embraces dune slacks, lakes, saltmarsh and woodland – quite an unusual combination in a relatively confined area.

West Gower

West Gower brings with it world-class coastal scenery courtesy of Worm’s Head out beyond the village of Rhossili, from where it’s an exhilarating walk along Rhossili Bay up to Llangennith and its campsite, popular with surfers.

Rhossili Bay

‘Bleak and barren’ was Dylan Thomas’s rather curt observation of Rhossili Bay, which bears the full brunt of the mighty Atlantic swell at the far western tip of the peninsula. It’s fair to say that most visitors would be inclined to disagree with Thomas’s assessment, for this is one of Wales’s great beauty spots, a 3-mile stretch of smooth sand, 2 miles of which is owned by the National Trust.

Moreover, dogs are permitted on the beach all year round. So named because the Vikings thought it resembled a sleeping dragon, Worm’s Head is the most sought-out landmark on Gower, and one of the most memorable geographical landmarks anywhere along the British coastline, up there with the likes of Durdle Door and the Old Man of Hoy.

Llangennith

The big deal in Llangennith is its beach, a mile or so from the village down Moor Lane. A yawning expanse of dune-backed golden sand, it’s one of the best surfing beaches in Wales, popular with everyone from hot locals to complete novices.

There’s an excellent surf school based at the Hillend campsite, which is where most people end up staying anyway. Pleasant as it is, there’s very little to Llangennith itself, save for the church of St Cennydd on the grassy village green, and the popular King’s Head Pub opposite.

Mid Gower

Mid Gower is defined by the brackeny backbone of Cefn Bryn, a 500ft-high sandstone ridge that stretches all the way across the peninsula to Rhossili Downs. Inland Gower’s main settlement is Reynoldston and it’ll come as little surprise to learn that its focal pint, sorry, point, is the pub, and a fine one it is too.

From Reynoldston, the road heads northwest to Fairyhill, beyond which one road heads west to Llangennith and the other east to the village of Llanrhidian, whose historic and much-loved pub, the Dolphin Inn, closed in 2020. However, there have been rumblings that this may reopen in some form or other under new owners, so watch this space.

North Gower

Beyond the sheep-filled fields of the central tract – a long, red sandstone ridge – the north coast is Gower at its most elemental: spectral castle ruins, vast acres of marshes and mudflats, cockle beds, and the odd, time-warped village. It’s also where Wales’s finest meat, Gower saltmarsh lamb, hails from.

Indeed, with its fertile farmland, endless coastline and mild winters, Gower is blessed with an exceptional natural larder: shellfish, Penclawdd cockles, asparagus and seaweed – tons of the stuff – all of which finds its way on to menus both here in Gower and beyond.

St David’s Peninsula

St David’s Peninsula is Wales at its windiest, wildest best – a corrugated coastline gashed with coves and beaches.

While St David’s may be the cultural showstopper, there are rewards of a different hue to be had elsewhere. The peninsula’s greatest offshore treasure is Ramsey Island, one of Britain’s great seal-watching destinations and a gathering site for thousands of visiting birds each spring and summer.

There is of course wonderful walking to be had here: for many, the peninsula is one of the standout sections of the coast path, but there are plenty of shorter hikes (albeit likely to incorporate elements of the coast path), for example a circular walk to Carn Lidl via Whitesands Bay and St David’s Head, or, in the opposite direction, a circular from St David’s via St Non’s Chapel and Porthclais.

If that’s too sedate, there are more invigorating ways to spend your time here, such as coasteering – an activity that originated right here.

What to see and do along St David’s Peninsula

Solva

Sitting at the end of a long, deep ria (drowned glacial valley) framed by totem-like cliffs, this is actually a village of two parts – Upper and Lower Solva – though everything of interest is in Lower Solva and its long main street, liberally sprinkled with shops, galleries, restaurants and pubs.

The perfect complement to time spent down in the harbour or browsing the shops and galleries is a walk up to the Gribin, the eastern headland guarding the entrance to the harbour, which you’ll walk along anyway if you’re on the coast path. As well as the remains of an Iron-Age earthwork, you’ll be rewarded with spanking views of St Bride’s Bay.

St David’s

In 1995, the Queen conferred city status on St David’s – the country’s spiritual and ecclesiastical centre. In all but status, St David’s is a large village, and were it not for the crowds, there would be no reason for thinking otherwise.

St David’s is not a big place and you could easily walk from one end of the city to the other in 10 minutes. In terms of sights, St David’s Cathedral and the Bishop’s Palace complete one of the most exceptional ecclesiastical enclaves in the British Isles, but once you’ve exhausted those two, there’s little else to see here and you can turn your attention to exploring the rest of the peninsula.

Whitesands Bay

As far as Pembrokeshire’s beaches go, Whitesands Bay (where the sand isn’t very white) garners plenty of accolades, and there’s no doubt it’s a beauty: long, wide and big enough to lose yourself on should you start to feel crowded out.

Moreover, the surf’s terrific, though bodyboarders will appreciate the waves here just as much. There’s also good parking and a café here, while lifeguards patrol a section of the beach in front of the café during high season.

St David’s Head

From Whitesands, there’s a fabulous section of coast path out towards St David’s Head, which should inveigle even the most reluctant walker. Starting at the car park, the path heads upwards, edging the precipitous cliffs before dropping down into the valley and skirting the soft blonde sands of Porthmelgan Beach, another of the coast’s now not-so-secret beaches.

So long as you’ve picked the right day, it is as gorgeous as everyone makes it out to be, though there are strong currents here so be careful. Back on the path, the long thin spit of St David’s Head lies less than a mile ahead. On your approach, you’ll see the remains of prehistoric hut circles, while St David’s Head itself is the location for an Iron-Age coastal fortress.

Ramsey Island

Ramsey Island is an indeterminately shaped island that manifests two distinct geological entities: a northern half that is largely sedimentary, and a southern half that is volcanic. If you are on a landing trip, there’s an easy but very satisfying 3½-mile circuit of the island, which traverses its three moderately sized peaks including the highest, Carn Llundain, at 446ft (136m).

Covering some 640 acres and owned and managed by the RSPB since 1992, the island was originally the property of the Church, until it was passed into private hands and run as farmland, which included a deer park. Red deer have proved to be a resilient presence on the island, and there’s a good chance of seeing some.

You’ll also get to see grey seals, hundreds of ’em, dozing on the pebbly beaches and in the sea caves pressed into the cliffs all around the island. Although there is a small resident population here year-round, their numbers are swollen in autumn (September/October) when hundreds of pups, up to as many as 700, are born here, making Ramsey one of the largest breeding colonies in Britain.

Swansea

‘An ugly lovely town’ was Dylan Thomas’s oddly contradictory assessment of Swansea, Wales’s second-largest city, with a population of around 310,000.

Like Cardiff, Swansea was once a great centre of industry. But more than that, it could lay rightful claim to being Wales’s first industrial town, and by extension the birthplace of modern Wales.

One enthusiastic observer in the late 18th century suggested that, ‘Swansea, in point of spirit, fashion and politeness, has become the Brighton of Wales’. A little misplaced, maybe, and while it certainly has spirit, few would contend that Swansea has ever been fashionable.

But there has been much progress and no little ambition in recent years, which was kickstarted by the redevelopment of the old docks, now a glitzy waterfront zone of swanky apartments and office blocks.

What to see and do in Swansea

The city centre

South of Castle Square, freshly tarted-up Wind Street (pronounced as ‘whined’) is Swansea’s notorious nocturnal thoroughfare, packed cheek-by-jowl with chain bars, pubs and restaurants, though there are one or two places with genuine personality here too – that said, Wind Street is not for the faint-hearted at weekends.

Heading west from Castle Square brings you to the main shopping precincts, bounded by The Kingsway to the north, Oystermouth Road to the south, and the Westway. The one thing likely to detain you here is the excellent, glass-domed indoor market, which opened on this site in 1830 and is still the largest in Wales.

The best reason to venture out this way is the wonderful Glynn Vivian Gallery. A Grade II-listed building dating from 1911, the gallery has numerous rooms set around a glorious atrium. Born into wealth as the son of a copper magnate, Richard Glynn Vivian dedicated his life to travel, which in turn fed his insatiable desire to accumulate – he bequeathed his entire collection to the museum.

The Maritime Quarter

Swansea’s three key attractions are concentrated to the south in and around the regenerated dockland area, aspiringly called the Maritime Quarter. The city’s urban transformation has continued apace with the arrival of Copr Bay in 2022 – a major new cultural and leisure hub costing a cool £135 million and centred on the spectacular Swansea Arena.

The adjoining bridge – freckled with laser-cut origami shapes – has inevitably already acquired various sobriquets, among them ‘the Crunchie’ and ‘the Taco’. The Copr Bay development also incorporates a newly landscaped coastal park and a cool café/bar.

Dylan Thomas Centre

Considered disposable by Swansea Council, the Dylan Thomas Centre is a brilliant tribute to Wales’s most revered poet. The centre occupies the dignified Old Guildhall building, dating from 1829, and was originally opened by the former US president, and lifelong Dylan fan, Jimmy Carter in 1995.

Entitled ‘Love the Words’, the exhibition (encompassing the largest collection of Thomas-related material in the world) is thoroughly absorbing and by the end of your visit there’s not much you won’t know about the man and his life.

Arranged chronologically, it therefore begins with his childhood in the Uplands area of the city, where he schooled in Mirador Crescent before going to Swansea Grammar, although he cared little for academia, instead preferring to spend his time reading, writing and debating, or playing cricket.

There’s intensely personal stuff here too, such as a hastily scribbled note on the back of a bank paying-in stub where Thomas writes ‘my darling own dear Cat, I love you for ever and ever…I had no time, from the BBC, to get to bank between 10 & 3.’

National Waterfront Museum

An old warehouse zhuzhed up with ultra-modern glass, steel and slate, the National Waterfront Museum emerged from the ashes of the old Welsh Maritime and Industrial Museum formerly based in Cardiff. Nearly 20 years after it opened, some of the exhibits could do with freshening up, but it’s still an excellent introduction to Wales’s industrial might.

There are some big bits of machinery of course, including a magnificent 1907 Robin Goch (redbreast) monoplane, a working replica of Trevithick’s engine (the original did grace the old Cardiff Museum, alas not so here), and a lovely old Mumbles tram – what the locals wouldn’t give to have that reinstated.

Swansea Museum

An appealingly old-fashioned collection in a grandiloquent Greek-revival building, Swansea Museum was established in 1841 by the Royal Institution of South Wales, making it Wales’s oldest museum. There is likely to be something for everyone to enjoy here, whether that’s the vast collection of ceramics, or its extensive archaeological treasures.

In 1823, the remains of a skeleton dubbed the Red Lady of Paviland, but who was actually a man, were discovered in a cave on Gower’s southern peninsula, and subsequently identified as being the oldest ever found – but before you get too excited, what you see here are replica bones, as the original ones are currently reposed at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, much to the vexation of locals.

Dylan Thomas Birthplace

Halfway up steep Cwmdonkin Drive, in the urbane, middle-class enclave of Uplands, a 30-minute walk west of the centre, a blue plaque marks out an ordinary suburban semi as the birthplace of Dylan Thomas.

There’s nothing original here from Dylan’s time but the house has been faithfully recreated to evoke the atmosphere of early 20th-century Swansea, with tiled hearths in the front room, a deep cast-iron claw tub in the bathroom and original books from 1914 in his father’s old study – in fact such is the owner’s commitment to authenticity that this is the one room visitors are allowed to smoke in, just as D J Thomas did.

Tenby

In the endless debates about Britain’s most attractive seaside resort – pointless but good fun – Tenby is usually a frontrunner.

One thing is for certain: its setting is peerless, and this much you’ll appreciate when you reach The Norton and observe the curve of terraced buildings in all their pastel-coloured glory – mint green, salmon pink, lemon yellow, sky blue – above the tiny, stone-built harbour, itself surrounded by piles of lobster creels, with fishermen’s cottages tucked into every nook and cranny in the cliff.

Tenby’s charms of course are no secret, and its streets and beaches can be tainted by the sheer numbers of tourists and day-trippers who flock here during the summer. But come any other time and this spectacular Welsh seaside town will leave a lasting impression, for all the right reasons.

What to see and do in Tenby

Town walls

Strengthened by Jasper Tudor (Earl of Pembroke and uncle of Henry VII), about half of the original 20ft-high town walls survive intact, including the Five Arches, about halfway along. Described by Augustus John as like ‘a piece of cheese gnawed by rats’, this semicircular barbican was used as an everyday entrance by town citizens, but unbeknownst to invaders had lots of hidden lookouts for surprise attack.

So enamoured were the locals with their walls that in 1989 they founded the Walled Town’s Friendship Circle, which some 150 other walled towns have since joined. Head through the arches and you’ll find yourself on St George Street and now in the thick of it: cafés, restaurants, ice-cream parlours and sweet shops.

St Mary’s Church

The first thing you notice upon entering the mostly 15th-century St Mary’s Church – a cool, quiet refuge from the hubbub outside – is the size of the place, looking much bigger inside than it does out. It’s effectively a triple-naved church, so wide are its north and south aisles (as are the dividing arches), with all three taken up by rows of long, bleached pews covering almost every square inch of floorspace.

By far the most compelling aspect of the church is the nave’s wagon ceiling, which runs all the way from the west door to the high altar: a panel design, its warped-looking beams bear a total of 75 carved bosses that were gilded as recently as 1966.

The building is rich in memorials, a clutch of them grouped together in St Thomas’s Chapel to the right of the chancel as you face it. Prominent here are the two chest tombs with effigies of Thomas and Jon White, superbly carved and only marred for chunks having been chipped off here and there, including most of Thomas’s face.

Merchant’s House and the harbour

From the church, the town’s maze of rough cobbled streets dive down to the superb Merchant’s House on Quay Hill. A high and narrow three-floored Tudor dwelling, the house is certainly 15th century, but is thought to have medieval origins.

From the Merchant’s House, the street slopes steeply to the harbour, where people congregate around the wooden huts deciding which boat trip to take. Peer into the dockside arches with fishmongers selling the day’s catch. During the late 18th century, the town developed into a fashionable bathing resort thanks to the patronage of William Paxton.

Spreading away from the harbour is the great golden expanse of North Beach, one of Wales’s most-photographed stretches of sand, partly because of its spectacular backdrop. Smack bang in the middle of the beach is the pronounced mound of Goskar Rock.

Castle Hill

From the harbour, a slipway leads down to Castle Beach, while a path veers left on to Castle Hill and Tenby Museum and Art Gallery, one of the most attractive small museums in Wales. Packed to its rafters with biological, geological and nautical artefacts, it’s the gallery that holds the real treasures, particularly a clutch of paintings by Augustus and Gwen John.

From the museum, follow the path down and around to the Victorian bandstand, where you can savour the wide-screen panorama. There’s more Victoriana at the top of Castle Hill courtesy of the statue of Prince Albert. Hewn from Sicilian marble, the statue could certainly do with a clean.

The most compelling thing on Castle Hill – in Tenby in fact – is the enormous RNLI station, which was built on top of the old town pier (opened in 1899 and all but demolished in 1953) to replace the old lifeboat station close by. Opened in 2005, it’s a magnificent structure, and inside there’s an equally magnificent vessel: the RNLB Haydn Miller, which you can view up close.

Caldey Island

Two miles offshore, Caldey Island – whose name was reputedly derived from the Viking Keld Eye, meaning ‘Cold Island’ – has been a place of God for more than 1,400 years, ever since Celtic monks pitched up here in the 6th century.

Living a life of austere simplicity, the monks here take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience and observe a rule of silence between 19.00 and 07.00. In addition to study and prayer, the third tenet of their rule is work, and here the brothers cultivate chocolate, shortbread, cosmetics and perfume, samples of which you can buy in the village shop.

From the jetty, it’s a short walk to the island’s main settlement, consisting of no more than a post office (with a small museum), a perfume shop selling the monks’ wares, and some sweet little tea gardens, from where you can see the imposing abbey itself.

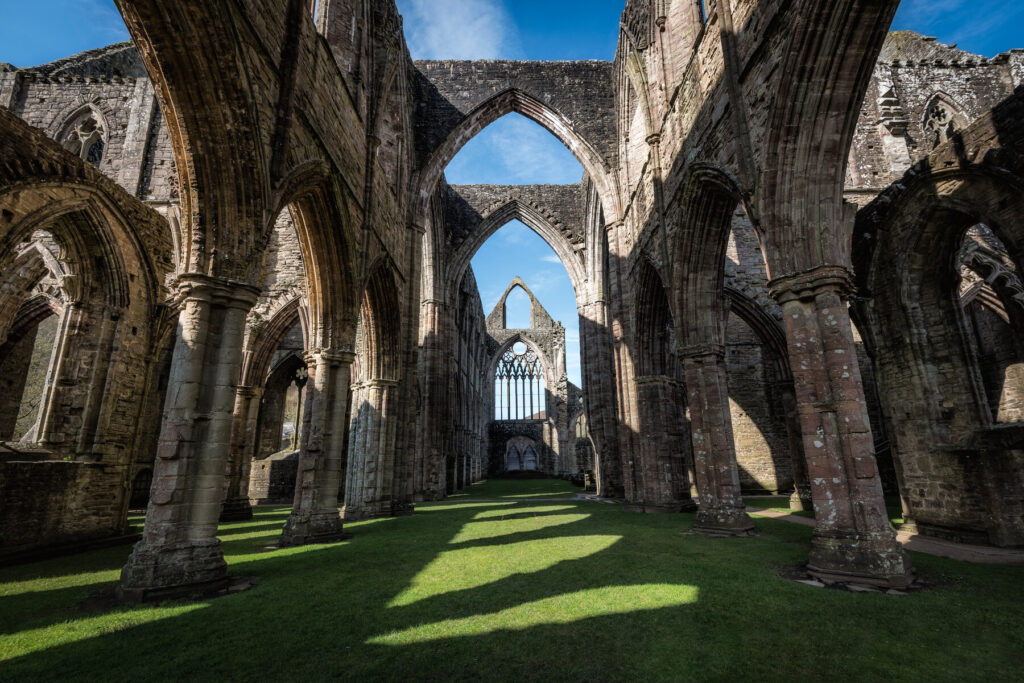

Tintern Abbey

No matter how many times you see it, Wales’s Tintern Abbey is always a majestic sight, and it’s little wonder that this place has inspired writers, painters and poets over the centuries, from the likes of Snyed Davies who extolled the glory of the abbey ruins in his 1745 poem, Describing a Voyage to Tintern Abbey, in Monmouthshire, from Whitminster in Gloucestershire, to Turner and Wordsworth, both of whom were frequent visitors.

Founded by Walter FitzRichard of Clare in 1131, Tintern was only the second Cistercian house in Britain after Waverley in Surrey (1128), and initially home to 13 choir monks from l’Aumône in Normandy, in addition to the abbot. The abbey’s subsequent patronage included the Earl of Pembroke, William Marshal I and the Bigod Earls of Norfolk.

Consecrated in 1301, this ushered in a period of great prosperity for the abbey, which lasted until 3 September 1536 when it was surrendered to Henry VIII’s officials following the dissolution of the monasteries. Appropriated by Henry Somerset, Earl of Worcester, many of the monastic buildings were subsequently employed as cottages and workshops for labourers from the nearby wire and ironworks.

Inside the abbey

Beyond the reception, the path leads straight ahead to the Warming House, which, kitchen aside, was the only part of the abbey permitted a fire. After hours spent between the icy chill of the church, cloisters and dorms, this would have offered welcome respite for the monks.

The Warming House is flanked on one side by the Day Room (aka Novices’ Hall) – where monks would engage in various tasks such as writing manuscripts – and on the other by the refectory, a deceptively large space whose ornate stone doorway and slender window columns hint at its former splendour; you can still see the serving hatch adjoining the kitchen and the chute for dispensing waste.

Collectively these quarters were among the first buildings constructed here at Tintern, around the mid 13th century. A later, 14th-century addition to the complex was the abbot’s residence, which ranged across an extensive area northeast of the church and comprised a house (note the fireplace), hall and chamber, the latter with its own private chapel, in keeping with the abbot’s high status.

The rest of the site is consumed by the knee-high remains of the infirmary buildings, comprising hall, kitchens and cloister. Almost a mini monastery in itself, this is where the needs of the sick and elderly monks would have been attended to. Seek out, too, the extant drain, an ingenious example of medieval water management.

The church

Constructed in the shape of a cathedral, the church is the abbey’s great glory and one of the finest specimens of Gothic architecture in Britain, if not Europe.

Upon entering the church through the mighty west front, whose skeletal seven-light window retains its exquisite stone tracery, Coxe commented that ‘the eye passes rapidly along a range of elegant gothic pillars…from the length of the nave, the height of the walls, and the aspiring form of the pointed arches, first impressions are those of grandeur and sublimity.’

Bar the roof, an almost entire shell remains, and yet despite being stripped of almost all its ornamentation, it exudes a befitting sense of authority. Beyond the six bays that comprise the high and wide three-aisled nave, four massive cross-arms mark the divide between the nave and presbytery, and the north and south transepts.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to South Wales:

Related articles

Modest and slow paced, this historic town is the perfect place to spend a weekend.

From staggering stone-built strongholds to remarkable 15th-century fortifications.