Archaeologists and art-lovers, hikers and historians, oenophiles and ornithologists: all will take home unforgettable memories from a trip to Albania.

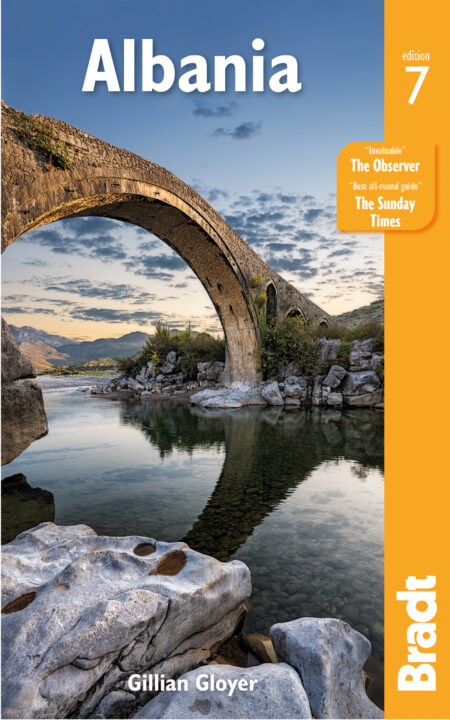

Gillian Gloyer, author of Albania: the Bradt Guide

A holiday in Albania has something for almost everyone. Less than four hours’ flight from the UK, its towering mountains provide one of Europe’s last refuges for bears, wolves and the elusive Balkan lynx, while the country’s location on major migration paths makes it a Mecca for birdwatchers.

The complexity and richness of its archaeological sites rival anything in neighbouring Greece, with a fraction of the tourists. Its ancient cities, with their stone houses and cobbled streets, are UNESCO World Heritage Sites; its medieval castles are everything that castles are meant to be, with dungeons, water cisterns and vaulted tunnels. Delicious fresh food and local wines will delight gastronomes.

Albania has been independent only since 1912. It was the last country in Europe, apart from North Macedonia, to gain its independence from the Ottoman Empire and, in its first 30 years as a modern state, it was invaded and occupied, at different times, by all its neighbours. The government that took over in 1944 used a combination of terror, nationalism and isolation to retain power until long after the communist regimes elsewhere in Europe had fallen. Civil unrest bordering on anarchy overwhelmed the country in 1991–92 and 1997.

Given this history, it is not surprising that Albania is so little known. During the communist period, practically the only Westerners who visited the country were in organised groups – ornithologists, art historians or curious adventurers coming in on bus tours from neighbouring Yugoslavia – which were carefully escorted by watchful ‘tour guides’. During the turbulent 1990s, most holiday companies were understandably wary of including Albania in their itineraries. It is only in recent decades that travellers in any numbers have started to discover Albania’s beauty; its hidden medieval churches and very visible castles; its magnificent archaeological sites, with remains dating back two-and-a-half millennia; and, of course, its delicious fruit, vegetables, lamb and fish. Many visitors are drawn to Albania’s spectacular, remote wildernesses and special attention should be paid to these and to the outdoor activities which can be enjoyed in them.

Albania is easy to get to, by land, sea or air. There are hotels of at least reasonable standard everywhere. Road infrastructure continues to improve across the whole country. Increasing numbers of visitors are coming to Albania in their own cars or mobile homes, or renting a vehicle to give them more flexibility to explore. However, inter-city buses are a reliable and low-cost option for getting around the country.

For more information, check out our guide to Albania:

Food and drink in Albania

Food

Albanian cuisine is rich in Mediterranean ingredients such as olive oil, tomatoes and pimentos. Lamb, as you would expect in a mountainous country, is excellent, as is fish from Albania’s rivers, seas and lakes. Those who like offal will welcome the chance to try dishes that changing consumer tastes have all but eliminated from northern European menus.

Fruit and vegetables in Albania are delicious. The tomatoes taste of tomato, the watermelons remind you of something other than water, and the citrus fruit is tangy and refreshing. Aubergines, courgettes, green beans and okra figure prominently in summer, with cabbages, carrots and potatoes taking over in winter. It is a frequent boast in restaurants that all the food is organic (bio), but there is no system in Albania yet for certifying organic produce.

The lake fish koran (a species of trout unique to Lake Ohrid) and carp are usually available only near the lakes where they are fished, although you can sometimes find them in Tirana, at a price. River trout, too, seldom travel far. Fresh sea fish is readily available all along the coast and in the inland cities. The varieties that appear most frequently on menus are levrek (sea bass) and kocë (sea bream), both usually farmed, barbun (red mullet) and merluc (hake). Eels (ngjalë) are caught in the lakes and coastal lagoons and are much sought after there; they rarely make it to the cities. Prawns (karkalec) are landed by Albanian fishermen, and on the coast they are likely to be fresh; elsewhere you may wish to ask if they are frozen (ie: imported).

Traditional Albanian home cooking uses vegetables, yoghurt and cheese to make meat go further. Potatoes, aubergines, courgettes, peppers and cabbage are all stuffed with minced meat. Pieces of veal are simmered with aubergine, spinach or green beans, or braised in a terracotta pot with pickling onions (mish çomlek). For turli, different vegetables – carrots, aubergines, potatoes, okra or anything else the cook has to hand – are layered with slices of tomato around a veal joint and simmered. Fergesë is made with green peppers and onions, fried together and then mixed with egg and gjizë, a dry curd cheese, before being baked. Pieces of meat or liver are sometimes added to fergesë. In tavë Elbasani, or tavë kosi, yoghurt and eggs are beaten together and poured over pieces of lamb or mutton, before the whole thing is baked in the oven.

Drink

The draught wine in provincial restaurants is normally rather young, but can be very drinkable. Albanian wine in bottles is often excellent. The main wine producing areas are around Korça and Berati and between Lezha and Shkodra. The Bardha vineyard near Tirana produces outstanding wine in small quantities, difficult to track down but on the wine lists of a few Tirana restaurants. Most Albanian vineyards use well-known grapes such as Sauvignon and Cabernet, which are easy for them to sell in quantity. A few, however, are now moving towards a more high-end product using indigenous grapes such as Shesh (red and white), Pulës or Dëbinë (white) and Kallmet (red). Some of these vineyards can arrange tours of their production facilities and offer tastings of their own wines. For those who are unable to visit the vineyards, these wines are usually on sale in the duty-free shops at Tirana Airport.

Beer is brewed commercially in several towns and cities. Korça is home to the oldest brewery in Albania; others that are widely available outside their home region include Tirana, Kaon and Puka beers. The Tirana and Korça breweries produce dark beer as well as the more widely available lager; Puka offers an unfiltered version and Kaon a Weissbier.

Of the other Albanian alcoholic drinks, raki is the most widely consumed. Despite its Turkish name, Albanian raki is not flavoured with aniseed as it is in Turkey. It is a clear spirit, usually distilled from grape juice, and drunk as a morning pick-me-up, an aperitif, a digestif, or at any other time of day. Albanians also make raki from mulberries (mani), brambles (manaferre) and practically any other soft fruit they can lay their hands on. In Slav-speaking villages raki is distilled from plums, as it is across the border in former Yugoslavia. The Berati- based vineyard Çobo makes excellent walnut raki. Another unusual raki is that made from the fruit of the strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo) called mare in Albanian. The best raki is homemade; commercially bottled products are widely available in shops.

Health and safety in Albania

Health

Albania is no more dangerous from a health point of view than any other country in southeastern Europe. It is a good idea in general to keep up to date with vaccinations against tetanus, polio and diphtheria. In the UK these are normally given together and should be boosted every ten years. Other vaccinations that are worth considering, depending on what you plan to do in Albania, are those against hepatitis A and B. There have been no cases of human rabies in Albania since the 1970s. Malaria was eradicated from Albania in the 1930s.

If you are involved in an accident or a medical emergency, call an ambulance on 127. Outside the big cities, however, it may be quicker to use a taxi; say to the driver ‘tek urgjenca’, meaning ‘to accident and emergency’. You will be given the best treatment possible.

In Tirana and other cities, there are now good non-state hospitals, with the latest technological equipment, which offer a full range of medical services up to and including heart bypasses and neurosurgery. The standard of dental practices is very variable – there are some good ones in Tirana – and you should seek local advice, perhaps at your hotel.

In small towns and rural areas, health care can be a problem. State hospitals are often short-staffed, with equipment that is old and sometimes does not work at all; many rural clinics have closed altogether. If you intend to travel outside the cities and are reliant on a specific medication, you should ensure you take an adequate supply with you. During the Covid-19 pandemic, summer health centres opened at places popular with tourists, such as beach resorts; it is possible that this innovation may continue in future years.

For minor ailments, remedies such as painkillers or antiseptic ointment can be bought over the counter in pharmacies. Opticians can make repairs to spectacle frames or replace lenses fairly quickly. Disinfecting solution for contact lenses is stocked by a few opticians in Tirana and other big cities. The international-style supermarkets in Tirana and other large cities stock tampons.

Safety

Albania is a safe country for visitors. Its traditions of hospitality mean foreigners are treated with great respect; almost all Albanians will go out of their way to help you if you are lost or in trouble. In general, violent crime in Albania happens either within the underworld of organised crime or in the context of a blood feud. A foreign visitor is highly unlikely to come into contact with either of these categories.

Nevertheless, there are poor and desperate people in Albania, as there are in any other country, and thefts and muggings do occur. It is foolish to flash expensive watches, phones or cameras around, especially in the peripheral areas of towns where the poorest people tend to live. Some travellers carry a dummy wallet with a small amount of cash in it, so that in the event of a mugging they can hand this over instead of their ‘real’ wallet full of dollars or euros.

The greatest risk most people in Albania face is on the roads, where traffic accidents are very frequent and the fatality rate is one of the highest in Europe. Until a decade or so ago, Albanian roads were so bad that it was difficult to drive fast enough to kill anyone. Now, though, cars zip along newly upgraded highways which are also used by villagers and their livestock. There is no stigma attached to drink-driving and little attempt is made to check it.

Female travellers

Foreign women are treated with respect in Albania, although the same respect is not always shown to Albanian women. Domestic violence, in particular, is very prevalent and almost always unreported. Outside the home, however, women are at less risk of sexual assault or rape than in any northern European country. Of course, these crimes are not completely unknown, but they are rare enough to make headline news when they happen.

Black and minority ethnic travellers

Black and minority ethnic (BAME) visitors to Albania sometimes find themselves on the receiving end of treatment that, although not racist in its intent, can make the visitor feel uncomfortable – for example, children or even adults stroking or pinching your skin out of curiosity. Occasionally, however, BAME visitors have been verbally and even physically abused by groups of racists. There have also been sporadic reports of racist behaviour by some hotel owners.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Homosexuality is legal in Albania. A law passed in 2010 specifically protects its citizens against discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation, while a 2013 amendment to the criminal code added sexual orientation and gender identity to the grounds for charges of hate crimes. However, it is still rather taboo and the LGBTI community generally keeps a low profile. Almost no public figures are openly gay. That said, however, lesbian or gay travellers are unlikely to encounter hostility or discrimination in Albania, assuming they behave with reasonable discretion (as they probably would in an unfamiliar town in their own country). A couple of bars in Tirana advertise ‘gay-friendly’ evenings.

Travellers with a disability

In 2013, Albania ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities, which sets targets for improving legislation, access and employment for people with disabilities. This was a positive step and progress has been made since then. However, Albania is still a challenging destination for people with physical disabilities, particularly users of wheelchairs. Most communist-era museums and other public buildings were built with steep stairs and other obstacles, although more and more now have ramps which provide access at least to the ground floor. Outside the central areas of the larger cities, few pavements in Albania have dropped kerbs and pedestrian crossing lights rarely have acoustic signals. Braille is not widely used. Public buses and most taxis are completely inaccessible for wheelchair users. All that said, however, people with reduced mobility will find Albanians eager (possibly overeager) to assist when necessary.

Travel and visas in Albania

Visas

Citizens of many countries are not required to obtain Albanian visas in advance. Countries to which this visa-free system applies include all those in the European Union (EU) and European Free Trade Association (EFTA), all of Albania’s neighbours, the UK, Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand and the US.

The Albanian Foreign Ministry’s website carries information in English about visa requirements; a full list, with contact details, of diplomatic representation in Albania, including for countries that cover Albania from their embassies in other countries; and information on Albanian embassies throughout the world. Albanian embassies do not provide tourist information, beyond visa requirements and similar queries.

Getting there and away

By air

Albania’s main (and, until 2021, only) international airport is officially called Mother Teresa International Airport but more often referred to simply as Tirana Airport, even by the airport authorities themselves. Albanians often refer to it as ‘Rinas’, from the name of the village that once existed there. The IATA code is TIA.

From the UK, direct flights to Tirana are operated by British Airways, EasyJet and Wizz Air. A full list of airlines that operate scheduled flights into Tirana Airport, with their websites and the telephone numbers of their local offices, is available on the airport’s website. This also has real-time listings for arrivals and departures, details about flight schedules and other useful information.

By sea

For many northern Europeans, the cheapest and most convenient way to get to southern Albania is to take a flight to Corfu and from there the hydrofoil to Saranda. The journey takes about 40 minutes. There is at least one hydrofoil crossing a day, all year round.

Albania has good sea connections with Italy. The busiest route is Bari–Durrësi, with several ferry companies operating throughout the year. The crossing takes about 9 hours. There are also ferries to Durrësi from Ancona and Trieste, and to Vlora from Brindisi. The Italian website traghetti.it has details of all routes between Italy and Albania. A passenger route has been proposed between Durrësi and the Croatian ports of Rijeka and Zadar, and may start operating in the lifetime of this book.

By land

Visitors who bring their own cars into Albania should ensure that their vehicle insurance is valid there. There is no longer a ‘circulation tax’. Petrol and diesel are widely available everywhere except the most remote mountain areas. Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG) is available in petrol stations on major highways and in cities. For those with an electric vehicle, public chargers are not widespread – there are a few in Tirana, including one on Embassy Row, Rruga Skënderbeu – but availability will probably improve in the near future.

If crossing into Albania from Kosovo, there are practically no formalities beyond showing your passport. Women aged under 18 travelling without either of their parents should carry a notarised authorisation; this is intended to make life difficult for criminals trafficking women, rather than for the legitimate female traveller.

Getting around

Car hire

Self-drive cars can be hired at Tirana and Kukësi airports, outside the ferry terminal in Saranda, and in other cities and larger towns. A few companies offer the option of dropping the vehicle off in a different town from where it was picked up. For some of the routes described in this book, a small saloon will not be adequate. Many car-hire agencies have 4×4 vehicles available, although of course these are more expensive.

Some good options include:

Public transport

Public transport in Albania falls broadly into one of three categories; ‘inter-city buses’, ‘rural buses’ and ‘city buses’. They all operate daily, except in some remote areas where there is no Sunday service. The rail network is restricted to a couple of trains a day between Durrësi and Elbasani and Shkodra. The fares are cheap, but the trains are so slow and infrequent that they are not a realistic option for most travellers. There are no internal civilian flights at the time of writing.

Cycling

Adventurous cyclists will be spoilt for choice with all the ancient tracks across Albania’s mountain passes and along remote valleys. For short excursions on reasonably surfaced roads, bikes can be hired in several cities.

When to visit Albania

Climate

For most purposes, the best times of year to visit Albania are spring and autumn. In early spring, apple and cherry blossoms form little pastel-toned drifts by the roadside. By May, the snow is melting on the high mountain passes, water starts to flow again in the rivers and roses bloom in the lowlands. The long evenings of early summer are a good time to enjoy the terrace cafés in Tirana and the coastal towns. In June and September, the beaches are at their best, without the crowds of the peak tourist season, and the sea temperature is still comfortably high. By late autumn, the orchards start to blaze with bright orange persimmons and golden pomegranates.

Albania has a Mediterranean climate and in the lowlands it never gets really cold, although most buildings are poorly insulated and it often feels colder indoors than out. In Tirana, it is unusual for temperatures to stay below zero for more than a few days at a time. The southwest coast in particular is very clement, with average winter temperatures of 8–10°C. Most of Albania’s annual rainfall occurs between late autumn and early spring. Minor roads are not well drained and can become muddy and slippery during and after rain.

In the highlands, winter is a much more serious proposition. High-level hiking should only be attempted between June and September. Snow on arterial highways is usually cleared quickly, but the high passes on minor roads are normally closed for two or three months – or even longer in a harsh winter. Mountain towns such as Korça and Peshkopia are very cold at this time of year.

July and August are the warmest months and inland towns can become oppressively hot. In Gjirokastra and Berati, for example, summer temperatures are usually in the high 30°Cs and, with climate change, there are increasingly more days when the thermometer tops 40°C. Hotels and restaurants of a reasonable standard have air conditioning, but museums do not. Sightseeing in high summer is an exhausting business. On the coast, sea breezes keep the average temperatures down to a more tolerable 25–30°C. The best place to be at the height of summer is in the high mountains. Hikers and cyclists should be sure to have enough water with them; everyone else will never be far from a café.

Public holidays and festivals

Albania shuts down pretty much completely on 1 and 2 January (New Year) and 28 November (Independence Day). Particularly on 1 January, only a handful of cafés and restaurants open and all shops are closed.

On other public holidays, banks, museums and government offices are closed, while shops, restaurants, bureaux de change and other private businesses generally stay open. The major feast days of each of Albania’s religions or, if they fall on a Sunday, the Monday following them, are public holidays. The two which have fixed dates are the Bektashi festival of Nevruz, on 22 March, and 25 December, when both the Catholic and Albanian Orthodox churches celebrate Christmas. Moveable religious holidays are Catholic and Orthodox Easters (usually on different Sundays), Eid al-Fitr (Bajram i Vogël, the end of Ramadan) and Eid ul-Adha (Bajram i Madh).

Other holidays include Summer Day (14 March), International Workers’ Day (1 May), Mother Teresa Day (19 October) and Liberation Day (29 November). The last commemorates liberation from the Germans at the end of WWII which, since it was immediately followed by 45 years of communist rule, not everybody in Albania agrees is a reason for celebration.

What to see and do in Albania

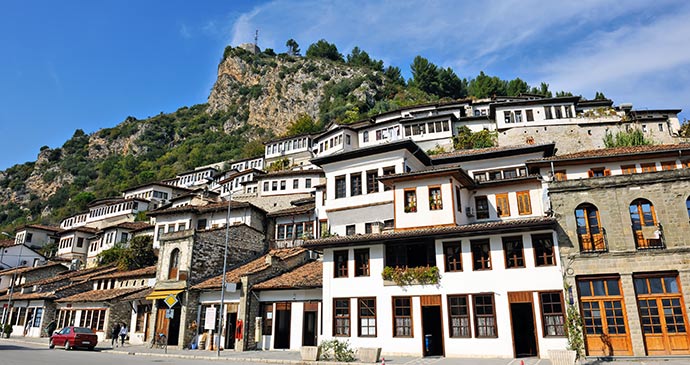

Berati

Berati is one of the oldest cities in Albania and one of the most attractive; the view of its white houses climbing up the hillside to the citadel is one of the best-known images of Albania. The citadel walls themselves encircle the whole of the top of the hill. Within them are eight medieval churches, one of which houses an outstanding collection of icons painted by the 16th-century master Onufri.

What to see and do in Berati

The castle

The citadel of Berati was first fortified in the 4th century BC by the Illyrian Parthini. At the same time, they also fortified the hill opposite, on the left bank of the River Osumi; the remains of the massive walls there, known as Gorica Castle, can still be seen among the trees. The pair of fortresses ensured that the whole river valley could be controlled and defended.

To get to Berati Castle on foot, the easiest way is to walk up Rruga Mihal Komneno (also known as Rruga e Kalasë, ‘Castle Street’) – the steep cobbled road through Mangalemi, one of the city’s protected ‘museum zones’.

Of the 42 churches that the castle walls once contained, only eight remain and, with one exception, they were locked up after the atheism campaign of the late 1960s. The exception was the Church of the Dormition of St Mary (Kisha e Fjetjes së Shënmërisë), a three-naved basilica that was built in 1797 on the foundations of a 10th-century church and which now houses the Onufri Museum, signposted from the inner entrance to the castle. The museum was redesigned in 2016 and the exhibition now covers two floors. Over a hundred beautiful icons, from churches in Berati and the surrounding area, are displayed. The earliest are from the 14th century, before icon-painters began to put their names to their work (this is because their purpose was to glorify God, not themselves).

Ethnographic Museum

Just off Rruga Mihal Komneno is a beautiful traditional house, built in the 17th or 18th century and converted in 1978 into Berati’s Ethnographic Museum. A visit to the museum is an excellent opportunity to learn about Berati architecture and find out more about people’s way of life until only a few decades ago. It was a family home until 1978; as in many other cases, the family was moved into an apartment to make way for the museum. They were eventually compensated for the loss of their property, but not until 2001.

Like traditional houses elsewhere in Albania, the ground floor was not used for living in, but for storage and household activities such as pressing olive oil or distilling raki. Part of the ground floor of this house has been converted to represent an Ottoman bazaar, with examples of traditional costumes and displays about the crafts traditionally practised in Berati, such as metalwork, felt-making and embroidery.

Solomon Museum

At the time of writing, this is the only museum in Albania that presents the lives and work of the country’s Jews. The museum was founded by the late Simon Vrusho, a prominent member of the Jewish community in Berati, and is run by his widow. It moved to its current premises in 2019; it takes about half an hour to look around and provides a good introduction to this little-known aspect of Albania’s history.

The exhibition consists mostly of nicely presented photos of Berati Jewish families and of local people who helped Jewish refugees during World War II. It also features the Kabbalist Sabbatai Zevi (1626–76), who came to Berati from Vlora, following his expulsion from Constantinople. Sabbatai was born in Smyrna (now in Turkey) and claimed to be the Jewish Messiah; his followers were known as Dönme (‘converts’). In Berati, he is believed to have been buried in Bilça, just outside the city, although some scholars maintain that he died and was buried in Ulqinj, now in Montenegro.

Historic mosques

Berati’s historic mosques are located fairly close together near the modern town centre. The Bachelors’ Mosque (Xhamia e Beqarëve), on the main boulevard, was built in 1827 for the use of the city’s (unmarried) shop assistants, and its external walls are beautifully decorated with wall paintings. The Leaden Mosque (Xhamia e Plumbit), so-called from the covering of its dome, dates from the first half of the 16th century. It is mentioned by the great Ottoman explorer Evliya Çelebi (1611–82).

The oldest of the three – and one of the oldest mosques in Albania – is the King’s Mosque (Xhamia e Mbretit), at the foot of Rruga Mihal Komneno, the street up to the castle. It has a beautifully carved and painted wooden ceiling, and a large women’s gallery. It is possible to see inside the mosque immediately after prayer times; at other times it is usually locked, although it can be opened for group visits.

Gorica

Three neighbourhoods of Berati are designated as ‘museum zones’, with restrictions on the alterations which may be made to the properties within them. Mangalemi and Kalaja (the castle) are two; the third, Gorica, lies on the other side of the River Osumi. The two sides of the town are connected by the Gorica Bridge, a narrow stone bridge built in the 18th century to replace the wooden bridge that had been used until then. A new road bridge in the western outskirts of the city has replaced the Gorica Bridge for most vehicles.

After the Ottoman conquest, Gorica became the Christian quarter; two churches survive there. There are information panels outside each of them, with a floorplan of the church and a map showing its position within Gorica. The opening hours below, also posted on the church gates, are more of an indication of intent than a reliable guide. It may be possible to contact a key-holder by calling the mobile number on these signs. The little Church of St Thoma is tucked into a corner of the cliff at the eastern end of Gorica, at the steps down from the footbridge. A shrine behind the church marks where a local saint is said to have left his footprint in the rock. The gate of St Thoma’s is a good viewpoint for the Castle and the houses of Mangalemi below it.

Butrint

The ancient city of Butrint, one of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites, is far and away the most-visited archaeological site in Albania, with visible remains spanning two- and-a-half millennia – from the first settlers in the late 6th or early 5th century BC to Ali Pasha Tepelena at the beginning of the 19th century AD. Then the site became overgrown and half-forgotten, visited only by the occasional artist (including the British poet Edward Lear), until 1928, when the Italian Archaeological Mission, led until his death by Luigi Maria Ugolini, began to uncover the city’s hidden treasures. After World War II, Butrint was once again abandoned and forgotten until the Albanian Centre for Archaeology began excavating there in 1956. Archaeological research has continued at the site ever since.

What to see and do in Butrint

The city

The earliest building below the acropolis was a sanctuary to the god of medicine, Asclepius, in what developed into the city’s monumental centre. In the 4th century BC, or slightly later, a defensive wall, with imposing gates at regular intervals, was built around the expanding lower city – a stretch of this, with large irregularly shaped blocks, can still be seen as you enter this area. Worshippers came to the sanctuary to be healed and, to meet their other needs, various other buildings were erected: a temple, in front of the shrine; a hostel for pilgrims or priests to stay – the so-called Peristyle Building; and, between them, a theatre, built with donations made to the god.

An inscription on the theatre seats dates its construction to the early 2nd century BC, although this was almost certainly an extension of an earlier, simpler theatre. To the side of the walkway leading into the theatre, inscribed blocks form part of the wall; these record the freeing of slaves, more than 500 of them, between 163 BC and 44 BC. Behind the Peristyle Building, a long portico (a stoa) once ran, with a well set into the hillside within it; the ropes that hauled water from this well over the centuries have worn deep grooves into its marble door.

The Roman aqueduct

The triangular fortress and the remains of the aqueduct, across the Vivari Channel, are easy to visit on foot. A delightfully low-tech cable ferry plies to and fro across the channel; the charges range from €0.50 for foot passengers, through €1 for cycles and €3 for saloon cars, to €10 for mobile homes. The gate into the triangular fortress is in the wall furthest from the ferry jetty – the southern side. Within the walls is a courtyard, in the centre of which is a circular building (perhaps a hamam, or steam bath, added later by the Ottomans). The western wall contains several small vaulted chambers, probably originally used as gunpowder magazines, workshops or stores. In the southwestern corner is an unusually shaped tower; there are good views of the city of Butrint from its upper floor and from the fortress battlements.

To reach the piers of the Roman aqueduct, continue along the edge of the Vivari Channel until you reach the fish traps and the building beside them, where there are beehives. Cross the little bridge there, and head slightly inland along a track that leads to an excavated area of the Roman suburb on the Vrina Plain. By the 2nd century AD, this included villas and a public bathhouse, with a large cistern that was supplied with water from the aqueduct. If you look along the wall of the cistern, you will see the bases of the aqueduct piers in a line running towards Xarra, the village on the hill. It is about 15 minutes’ walk from here back to the cable ferry.

Ali Pasha’s Castle

The expansion of Butrint in the 1st century AD meant new building not only on the Vrina Plain, but also at Diaporit, on the eastern shore of Lake Butrint. A large villa has been excavated here, with a bath complex, a peristyle and a mosaic-floored triclinium. The boatmen who hang around the entrance to the city can take you out to Diaporit.

They also offer trips to Ali Pasha’s Castle, which is on a little island at the edge of the marshes and can only be reached by boat. The trip out to the fortress meanders through the wetlands, with good opportunities to see waterbirds, and offers an entirely different perspective of the Butrint area. The fortress itself is beautifully constructed and is well worth exploring. The entrance to the Vivari Channel – with Ali Pasha’s Castle, the triangular fortress and the reconstructed Butrint Castle – can be seen from the deck of the Saranda-Corfu ferry (the view from the hydrofoil is not so good) and gives a good idea of the geography of the channel and the city.

Durrësi

The headland at the north of Albania’s Durrësi Bay forms a natural harbour in which ships have anchored since the 7th century BC. In antiquity it was known as Epidamnos, and the city that was built around it was called Dyrrhachion. In the 5th century BC, a popular uprising in Dyrrhachion helped to start the Peloponnesian War, which engulfed the whole of Greece from 431 BC to 404 BC.

What to see and do in Durrësi

The amphitheatre

The huge Roman amphitheatre, which is one of Durrësi’s main attractions, was built in the early 2nd century AD. The largest in the Balkans, it is elliptical in shape, about 130m at its longest point, with the arena itself measuring about 60m by 40m across. On the terraced seats there would have been room for about 15,000 spectators, about a third of the capacity of the Colosseum in Rome.

You can go down into the vaults below the rows of seats – the original steps, supplemented with less slippery modern ones, are just after the ticket booth – and see how the amphitheatre was constructed. The Romans alternated rows of brick with opus incertum, a mixture of stones and mortar, a technique designed to resist earthquakes. You can see this opus incertum in several places around the amphitheatre, including three full rows, well over 2m high, in one of the galleries. The technique was evidently quite successful, since most of the amphitheatre is still standing, despite Durrësi being hit by several strong earthquakes over the centuries. Behind the gallery, you can see the pens where the wild animals were kept; leading out from it is the tunnel through which the gladiators entered the arena. When the site was first excavated, 40 skeletons were discovered with their necks broken – could they have been unsuccessful gladiators?

Archaeological Museum

Durrësi’s Archaeological Museum covers the prehistoric, Hellenistic and Roman periods; the museum’s Byzantine collection will eventually be displayed on the upper floor. There are helpful information panels in English and Albanian. The fact that the city has been more or less continuously inhabited throughout its history means that most of it has never been systematically excavated. Many of the items in the museum were discovered by chance, as local people ploughed their land or as foundations were dug for the new high-rise apartment blocks.

A highlight of the museum is a whole case of terracotta faces and other body parts. These were votive offerings and were excavated in the 1970s at a sanctuary site northwest of the city. An incredible 1,800kg of fragments were recovered, of which those on display are obviously a selection. Many of the figurines represent Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love. Other female deities are represented too, including Artemis, the goddess of the hearth. Some scholars believe that the sanctuary was dedicated to her rather than to Aphrodite.

The city walls

Durrësi was first fortified in the Hellenistic period and then refortified shortly after the Roman conquest, in the 1st century BC. However, the oldest surviving walls are Byzantine, built during the reign of the Emperor Anastasios to replace earlier fortifications that a catastrophic earthquake in 348 AD had destroyed. These walls protected the city for several centuries, until the Byzantine Empire began to collapse and Dyrrachium and its valuable port fell prey to one invader after another. The medieval city within the walls covered an area of around 120ha.

Dyrrachium – or Durazzo, as it was by then known – was part of the Venetian Republic for the whole of the 15th century. One of the towers that the Venetians built, at the southern corner of their walls, is known as La Torra, now dwarfed by the high-rise Veliera development. Finally, in 1502, the Ottomans rebuilt the old fortifications and garrisoned their troops within them. An information panel at the city gate, which leads to the amphitheatre, shows an outline map of the fortifications as they changed over the centuries.

King Zog’s Palace

It was not until the Balkan Wars and Albania’s independence that the city re-emerged from obscurity; it was the new nation’s capital in 1914, under Prince Wilhelm of Wied, and then again from 1918 until the final decision to site the capital in Tirana.

King Zog I had a palace built here in 1927, a cream-and-pink villa up on the hill with marvellous views over the city and the bay. The building has now been returned to Zog’s descendants and is not open to the public.

The coast

A walk along Durrësi’s promenade takes about half an hour end to end, although most people will want to stop for an ice cream or a drink in one of the many bars and restaurants that line it. Two structures have been built out into the sea. The Ventus Harbor complex has trendy bars in the section nearest the beach and a hotel with a fish restaurant at the end of the pier. Further west, the so-called Sfinks is a public space, where locals come to sit and chat, fish from the steps or skateboard. In summer there are often live concerts there.

The beaches to the south of Durrësi have become very built up. Particularly in the peak tourist season (July and August), huge numbers of Albanians from landlocked Kosovo and North Macedonia fill the hotels and holiday apartments with which the coast is lined. At this time of year you should expect to find crowded beaches covered in litter, with the sea full of empty plastic bottles and crisp packets. On the positive side, this stretch of the coast has lively nightlife during the tourist season. If you are staying in the town centre and want a quick dip, the best option is one of the small beaches along Rruga Currilat, at the northern end of the city, beyond the Archaeological Museum. The hotels and restaurants along this stretch have reserved sections of sandy beach, with sun-loungers and parasols for which there is a small charge.

Korça

The people of Korça are justifiably proud of their city’s cultured and intellectual traditions. The city is home to a number of interesting museums and was one of the main centres of the Albanian cultural renaissance (Rilindja Kombëtare), which created the sense of national identity that ultimately led to the country’s independence from the Ottoman Empire. The first Albanian-medium school was opened here in 1887, with the first girls’ school following four years later, and the town was one of the focal points of the movement to standardise the Albanian alphabet.

What to see and do in Korça

National Museum of Medieval Art

Located in a purpose-built gallery, the National Museum of Medieval Art has the largest collection of icons in Albania, with 7,500 objects spanning seven centuries. It also has a fine collection of other liturgical art, such as hammered silver Bible covers and gold-plated crucifixes. Around 400 works are on permanent display, and the new museum provides space for conservation and restoration laboratories. The exhibition is spread over two floors and there is a lift.

The ground floor displays some of the most famous works by Albania’s best-known icon-painters: the 16th-century Berati artist Onufri, the 18th-century David Selenicasi and the 19th-century Katro (Çetiri) and Zografi families. But there was a long tradition of icon-painting before artists began to sign their work – Byzantine painters believed their work was to glorify God, not themselves – and the earliest works in the museum were painted by these anonymous artists. They include a 13th-century icon of St Nicholas, in lovely warm colours, from one of the churches in Vithkuqi, and 14th-century icons from St Mary’s Church in Mborja: another St Nicholas, this one almost monochromatic, and the stunning Archangel Michael in his armour. Dozens of icons fill the full height of the wall of the gallery, with a viewing platform from which to study them.

Archaeological Museum

The items displayed in Korça’s Archaeological Museum come from sites all over the southeast region, including the neighbouring districts of Devolli, Kolonja and Pogradeci. The whole region is a prehistorian’s paradise, with many very large tumuli (raised barrows) excavated – one of these, Kamenica, is open to the public and has an excellent site museum. There is a model of a tumulus in the Korça museum, showing how the graves were arranged concentrically.

The exhibition begins with a display of examples of the different types of tools used by Neolithic people (made of bone and horn as well as stone), their ceramics and their cult figurines. From very early on, they built lake-dwellings, using water to protect themselves from wild animals or human enemies. The site at Maliqi, excavated in the 1960s, was the largest in the Balkans (15ha) and was inhabited continuously from the Chalcolithic (3000–2200 BC) to the Archaic period (8th–7th century BC). A scale model of the Maliqi settlement illustrates how these wooden houses were constructed on stilts.

Rumanian House

This beautiful building now houses a museum devoted to the life and work of the photographer Gjon Mili (1904–14), well worth a visit for anyone with an interest in photography. Mili was born in Korça, but his family emigrated to Romania when he was four years old. From Bucharest, aged only 19, he emigrated again, this time to the United States, where he had a long and successful career with Life magazine.

His early training as an electrical engineer helped him to develop innovations in stroboscopic and stop-action images. Many of his photographs used these revolutionary techniques and these are displayed in the museum, along with tems of his photographic equipment. The exhibition is labelled in English and Albanian, and a 50-minute film about Mili’s work and life runs on a loop.

Town centre

The best place to begin exploring Korça is the city’s main square, where the tourist information office is. Dwarfing everything else in the square is the modern Red Tower (so-called, although it is not red). A lift (50 lek) takes you to a viewing platform from which there are good views of the city and the mountains that surround it.

From the square, the pedestrianised Boulevard Shën Gjergji leads first to the site of Korça’s original cathedral, which was built in 1905 and demolished in 1971 to make way for a new city library. The library is still there; however, when the boulevard was being pedestrianised and landscaped in 2014, the outline of the façade of the destroyed cathedral was set into the pavement outside the library. This is an admirable way of commemorating one part of the city’s history without destroying another.

Continuing up the boulevard, buildings of note include the house of Themistokli Gërmenji now a restaurant-with-rooms, the Museum of Education, and two beautiful examples of Korça architecture, the Rumanian House and the former Greek Consulate, now restored after many years of neglect. Facing down the boulevard, above a water feature, is the statue of the kilted Patriotic Warrior (cast by Odhisë Paskali, the sculptor of imposing statues in several other Albanian towns and cities).

The road running across the end of Boulevard Shën Gjergji is Boulevard Republika, which bisects the historic centre of Korça. Directly behind the Patriotic Warrior is the Orthodox Cathedral, built in the 1990s to replace the destroyed original. An information panel on the cathedral piazza has maps of the city and the region. Behind it lies a warren of streets of 19th-century houses, built of local stone, slaked with lime and roofed with small, curved tiles.

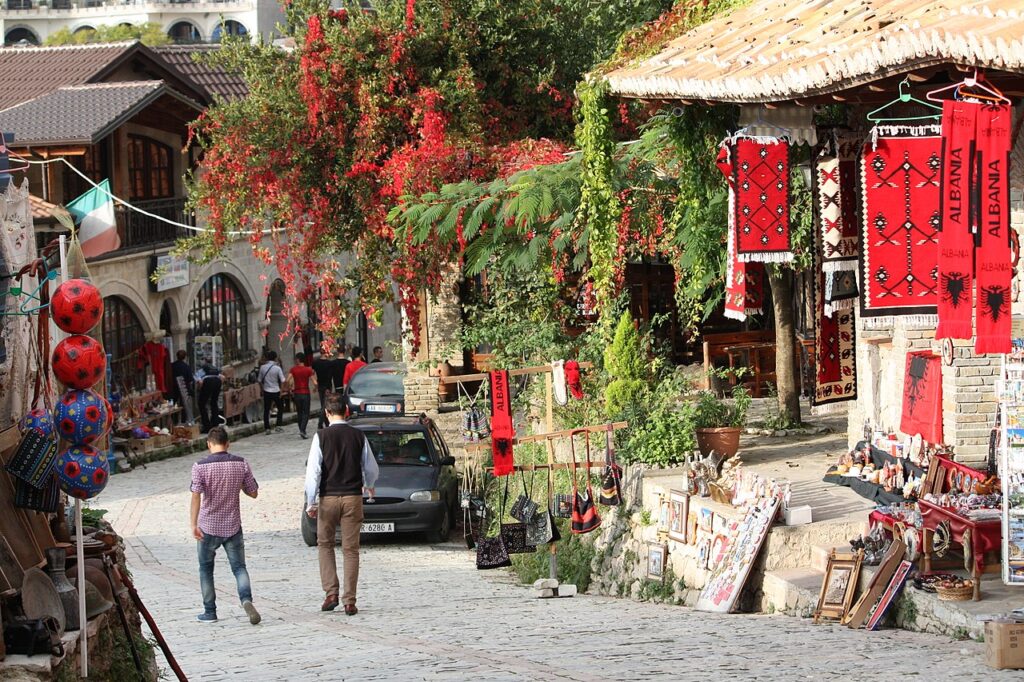

Kruja

Kruja has been fortified since ancient times – ceramics and coins from the 3rd century BC have been excavated there. The name comes from the Albanian word for the spring (krua), within the castle, which provided its inhabitants with water. The castle of Kruja was the centre of Albanian resistance to the Ottoman invasion in the 15th century, which was led by the great national hero Gjergj Kastrioti, also known as Skanderbeg. The buildings and museums within the castle walls, combined with the attractively restored bazaar area just outside them, provide an excellent introduction to Albanian history and traditions.

Kruja is the only town in Albania, apart from Saranda in the far south, which is really geared towards tourists; it is one of the best places in the country to shop for souvenirs.

What to see and do in Kruja

Kruja Castle

Kruja Castle stands on a crag overlooking the plain below the town, with views on a clear day out to the Adriatic (it can sometimes be seen from the plane as you approach Tirana International Airport). Within the castle walls are two very different museums, a historic Bektashi teqe and several other places of interest; you could easily spend several hours visiting these and wandering around the cobbled lanes in the residential area. The usual approach to the castle is up the cobbled street of the bazaar, which is closed to traffic. The road that runs parallel to it, around the back of the Panorama Hotel, lets you drive up to the castle entrance, but it is hard to park there. You should allow at least 2 hours for your visit, more if possible.

Historical Museum

On your left as you emerge from the vaulted entranceway is the Historical Museum, designed in 1982 in a sort of castle-ish style by the architects Pranvera Hoxha – daughter of the communist leader Enver – and her husband. The displays on the ground floor cover the Illyrian city-states, the Roman and Byzantine periods and the development of Albania’s medieval principalities. Then comes the story of Albania’s struggle against the Ottomans, told through maps, murals, books and replicas.

On the upper floors, there are scale models of Kruja and other castles, in a room with an etched-glass window showing the second siege of Kruja, and an exhibition focusing on Skanderbeg’s diplomatic efforts to rally support from other European countries for resistance.

Ethnographic Museum

One of the most interesting ethnographic museums in the country lies opposite the entrance to Kruja Castle (from where the sign is clearly visible). Its interest is partly due to the house in which it is located, designed for the prosperous and influential Toptani family and built in 1764. Laminated information sheets, in English and Albanian, explain the items on display.

The ground floor of the house is where the livestock were kept, the produce from the family’s lands was processed and the tools were made or repaired. There is a raki still, an olive press and equipment for making felt, one of Kruja’s traditional industries. The herdsman slept in the stable, with the sheep and/or goats, while the family lived upstairs, in rooms accessed from the covered balcony that was used as the living space in summer.

A walk around the citadel

Ordinary families still live within Kruja Castle, although in less luxurious houses than the Toptani house. A network of cobbled alleyways spreads downhill from the open area where the museums are. Down one of these is the castle’s beautiful little Bektashi teqe (100 lek). Bektashism is a Sufi order, founded in Persia in the 13th century; it was introduced to Albania in the wake of the Ottoman conquest and became widespread there in the early 19th century.

The Kruja teqe was built in 1770 (1191 in the Islamic hijri calendar) and is one of the oldest in the country. The olive tree in its garden is said to have been planted by Skanderbeg himself, as part of his campaign to encourage the other landowners of Kruja to plant olives.

The bazaar

The bazaar was restored in the mid 1960s, but the wood-built shops and cobbled streets have a very authentically Ottoman feel. The extra-long eaves and the gutter in the middle of the road mean that rain, or wet snow, falls off the roofs and drains downhill straight away – an unusual but effective architectural device. Many of the shops sell small souvenirs such as Albanian flags, copper plates and ashtrays in the shape of bunkers.

There are also traditional felt-makers, who produce slippers and the felt caps called qeleshe; carpet shops, in some of which you can watch the local women weaving the next batch of qilime (woven rugs; this is the same word as the Turkish kilim) with their ancient patterns; and antique dealers, where wooden butter paddles, cradles and intricately carved dowry chests pause in their journeys from highland villages to modern cities. Kruja’s bazaar is a laid-back place and nobody will mind if all you want to do is window-shop.

Lake Komani

The journey along Lake Komani deserves to be one of the world’s classic boat trips, up there with the Hurtigrut along the Norwegian coast or the ferry from Puerto Montt to Puerto Natales in Chile.

Lake Komani is narrow and twisting, with sheer cliffs right down to the water in some stretches, complete with breathtakingly high waterfalls. It is part of a huge hydro-electric system constructed in the 1970s and 1980s but, unlike Albania’s Lake Fierza further upstream, its topography was not much altered by flooding. In some places, the slopes are gentler and small clusters of houses can be seen. Here the people have terraced what little land is available, to pasture their livestock and grow maize and other crops. It must be a desperately harsh existence in these lakeside villages, where the only form of transport is a boat and where in bad weather you can be cut off completely from any shops, schools or medical care. Incredibly, some people apparently choose to live in even more remote spots, in the houses that can be spotted from time to time high up above the lake. Some of these houses are now abandoned, but others are still occupied, at least in the summertime, by hardy souls who work their land and build their haystacks as their ancestors did before them.

Thoughts of the hardship of these people’s lives need not deter you from marvelling at the magnificent scenery. Because the lake follows the twisting line of the river on which it is based, the boat at times appears to be heading for an unbroken cliff face. At the last moment, as it begins to turn, the break in the rock appears and the continuation of the lake can be seen through the gorge ahead. In these narrow stretches, the steep rocks on either side of you seem even higher than they really are.

The water is a deep jade colour, and the cliffs and trees climbing up above it are reflected in its intensity. In the less steep stretches, you can see the far-off summits of the Dinaric Alps, more than 2,500m high. Herons (Ardea cinerea) and pygmy cormorants (Phalacrocorax pygmeus) live around the lake, and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) and chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) can sometimes be seen up in the surrounding peaks.

Shkodra

Shkodra has been a highly significant city during most of its long history. It was the capital of the Illyrian state of the Ardiaeans from the 3rd century BC until the Roman conquest in 168 BC. The city was part of the Venetian Republic from 1396 until it was surrendered to the Ottomans, after a long siege, in 1479.

In terms of visitor attractions, Shkodra has one of Albania’s best castles (which is saying a lot), attractive domestic architecture and several excellent museums: the archaeological display in the Historical Museum, the huge collection of 19th- and 20th-century photographs in the National Museum of Photography, the Cathedral’s Diocesan Museum and the chilling Site of Witness and Memory.

The city is a good starting point for excursions into the wild and beautiful Albanian Alps. On the coast, there are important wetland habitats at Velipoja and Kune-Vaini, where many rare and attractive waterfowl and other birds can be observed.

What to see and do in Shkodra

Rozafa Castle

Shkodra’s castle stands above the confluence of its three rivers, the Drini, the Kiri and the Buna, and thus controls all but the northern approach to the city. It is an excellent place for a castle and has been fortified since Illyrian times, when the Ardiaean queen Teuta launched her attacks on the Romans from it. Traces of the Illyrian walls, constructed of large stones with no mortar, can still be seen at the entrance to the castle.

Most of what remains is Venetian and Ottoman. The outer walls follow the line of the hill; within, successive lines of fortification create three distinct areas, of which the most secure and easily defensible is the section at the narrowest part. The views from the citadel are wonderful, across Lake Shkodra to Montenegro, out to the Adriatic, and down towards Lezha.

You enter through the vaulted barbican gate to the first courtyard. A trickle of lime down the wall of this courtyard marks where people believe the eponymous Rozafa was walled up alive to guarantee the strength of the walls. Local women still gather here to acknowledge Rozafa’s sacrifice and to pray for their own fertility. The second enclosure was the main living area, with the barracks, stores and prison; the latter was in use until the early 20th century. The ruined church on your right was once Shkodra’s cathedral, a 13th-century building that remained in use even after the Ottoman occupation, until it was converted into a mosque in 1869. The circular, chimney-like structures here and there are the access points for water cisterns, constructed in the 15th century and fed by pipes running into them from all over the castle.

Historical Museum

The house of Oso Kuka, who died defending Shkodra against Montenegrin attackers in 1861, is now home to the town’s Historical Museum, and provides an opportunity to see traditional domestic architecture. From the street, a Shkodran house is just a windowless wall with a thick wooden door; once through this door, you find yourself either in a narrow entrance hall or, as in the case of Oso Kuka’s house, in a courtyard, with the house in the centre, far away from the surrounding walls.

The courtyard always had a well and this one has two: the original, from when the house was built in 1840, and a Venetian wellhead from the 15th century. Various large items recovered from the castle or found elsewhere in the area are displayed in the courtyard and in the garden behind the house. One of the most interesting is an Ottoman coat of arms, intricately carved in stone, which dates from the late 19th century and was found in the castle.

Site of Witness and Memory

From 1946 to 1991, a rather unassuming 19th-century house on Shkodra’s main boulevard became the regional headquarters of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. This innocuous name belies the political persecution and terror that emanated from this building for 45 years. The storerooms of the former Franciscan seminary were transformed into detention cells and interrogation rooms for the Sigurimi, communist Albania’s secret police. Thousands of people passed through these cells before they were sentenced; they were then either executed or sent on to other prisons or prison camps such as Spaçi.

Now the building has been transformed again, this time into a museum that commemorates those who suffered there. Panels in English and Albanian explain various aspects of Albanian communism, including the destruction of religious buildings, the anti-communist uprisings in northern Albania, and the public trials that took place in buildings around Shkodra. The events are brought to life through photos, documents, press cuttings and personal items belonging to prisoners. Finally, a walk of 50m leads to the corridor of prison cells, 29 of them plus a reconstructed interrogation room (a euphemism for ‘torture chamber’).

Diocesan Museum

Shkodra is the centre of Albanian Catholicism, the seat of the archdiocese of Shkodra and Pulti. The current archbishop, Angelo Massafra, is from the Albanian-speaking Arbëresh community of southern Italy.

St Stephen’s Cathedral was built in 1858, to replace the cathedral in Rozafa Castle which had been closed by the Ottoman authorities and converted into a mosque. The Russian tsar helped to fund its construction and Shkodra’s leading artists of the time designed and decorated it.

Slightly hidden behind the cathedral, in its former sacristy, the Diocesan Museum provides fascinating insights into the history of Catholicism in northern Albania, from its earliest traces in the 12th century. The exhibition is organised thematically, starting with archaeological finds from medieval monasteries and religious medallions. Documents, maps and photographs help to put the items on display into their proper context.

Thethi

About 50km northeast of Kopliku, at the head of the River Shala, lies the national park named after its largest settlement, the village of Thethi. The area was a tourist resort during (and, indeed, before) the communist period and its attractive, traditional features were accordingly maintained, while in other parts of highland Albania they were destroyed either deliberately or through neglect. Edith Durham visited Thethi in 1908, and described her stay there in her book High Albania. ‘Life at Thethi was of absorbing interest,’ she wrote. ‘I forgot all about the rest of the world, and… there seemed no reason why I should ever return.’ The modern visitor’s reaction is likely to be similar.

There are 200 houses scattered across this Albanian valley, although only a handful of families live there all year round. Most people spend the winter in either Shkodra or Kopliku, and return to Thethi in April or May, for the start of the tourist season; they leave again in September or October, before the harsh winter weather sets in. The traditional houses are built of stone, and roofed with shingles (wooden tiles). They were designed to be easily defensible – these mountains were once the heart of blood-feud territory and every family needed to be able to defend its menfolk against revenge. A traditional house of this kind is now the village museum.

Of special interest is the ‘lock-in tower’ (kulla e ngujimit), the only one remaining of its kind that is easily accessible to visitors. The beautiful little church dates from 1892. All buildings are found in the town’s main settlement and can easily be visited during a day trip. A longer stay in Thethi will allow you to explore further afield and see some of the beautiful natural phenomena in the park. There are also many longer treks for the fit and well equipped, including the popular hike across the Valbona Pass to Tropoja.

Tirana

Tirana was founded in the early 17th century by Sulejman Pasha Mulleti, who built a settlement in the area around the modern intersection of Rruga e Barrikadave and Rruga Luigj Gurakuqi. His statue stands today in the little square near that crossroads.

As well as its intriguing mix of architectural styles, Tirana has several very good museums and a range of cultural activities. It has hundreds of cafés; dozens of modern bars; numerous clubs, some with live music, particularly at the weekends; and an array of restaurants, many of them excellent. Tirana also has some infuriating aspects, mainly the appalling traffic congestion and noise. In general, however, the city centre is an attractive place to stay, and its excellent public transport links make it the best base for exploring the rest of Albania.

What to see and do in Tirana

Skanderbeg Square

Skanderbeg Square was once the hub of Tirana’s commercial and social life. Before World War II, the main market was here; the 18th-century mosque was where men met to chat, as well as to worship; and around the edges of the square were small shops and cafés. In the 1920s and 30s, the square became the city’s administrative centre, with imposing new buildings designed by Italian architects. Tirana’s citizens still refer to it as ‘the centre’. Now it has been completely closed to traffic and an underground car park has been built beneath its paved expanse.

On Skanderbeg Square’s northern side are the National Historical Museum and the Tirana International Hotel; to the west are the National Bank and the arterial roads called Rruga e Kavajës and Rruga e Durrësit; and the eastern side is entirely taken up with what was once known as the Palace of Culture, which still houses the opera house and the National Library. On the southeastern corner of the square, the 18th-century Mosque of Et’hem Bey is one of the few really old buildings left in Tirana, and is perhaps also the most beautiful. Its minaret was shattered in the Battle for the Liberation of Tirana, but it was subsequently repaired, and the mosque’s status as a Cultural Monument kept it from being damaged or destroyed during the atheism campaigns of the late 1960s. There are frescoes on its exterior walls and more wall paintings inside the mosque, all painstakingly restored in 2019–20. Visitors are admitted except during prayers; shoes must be removed at the entrance, before stepping on the carpet, and women must cover their hair.

National Historical Museum

Dominating Skanderbeg Square is the National Historical Museum, with its huge mosaic mural above the entrance. The museum was opened in 1981 and the mural is an excellent example of the nationalist narrative fostered during the communist period. It depicts the sweep of that version of Albanian history: Illyrian warriors, smiling peasants, the fighters and intellectuals who won independence from the Ottoman Empire, and brave male and female partisans, all being led into the glorious future by a Mother Albania figure.

You should allow an absolute minimum of 2 hours to look round the whole museum. There are many interesting things on display, with helpful maps and information on multilingual panels. Each display case usually has a summary in English and French. On the ground floor – the prehistory, antiquity and late antiquity sections – some of the individual exhibits are labelled in English and French as well as Albanian. The exhibition is arranged in rough chronological order, and starts with prehistoric finds from the Stone, Copper, Bronze and Iron ages. There are maps of Illyrian tribes and city-states at different points in time, and examples of Illyrian jewellery, coins and votive objects in terracotta and bronze from the 3rd to the 1st centuries BC.

Archaeological Museum

Although the National Historical Museum holds the best-known objects from Albania’s archaeological heritage, the collection in the Archaeological Museum, located within the Centre for Albanology Studies in Mother Teresa Square, is much more extensive. Few of the artefacts are labelled in English, but in most cases the labels merely indicate provenance, so geographical rather than linguistic knowledge is what is required. Some of the curators speak good English and, their time permitting, they are usually pleased to explain the collection to visitors.

The first two rooms are devoted to the Stone, Bronze and Iron ages, with some particularly nice spear- and axe-heads, and a fine iron helmet. Then the artefacts from Illyrian cities begin, which will be of greater interest to visitors who are not prehistory specialists. Lovely little figurines in bronze and terracotta, including a delightful little bronze dog from Antigonea, are perhaps the most attractive items in these cases, but there is also jewellery and pottery to admire, and a well-preserved helmet complete with nose and cheek guards. The Roman period is represented with statuary, some fine glassware, inscribed tombstones (some with identifiably Illyrian names), and inscriptions from Victorinus’s Wall, built around the ancient city of Byllis.

The Tirana Mosaic

Tirana’s only visible Roman remains, the Tirana Mosaic, was discovered during construction work in 1972. The original Roman building seems to have been the villa of a 1st-century AD winemaker. Two of his (or her?) amphorae are on display at the site, along with other items excavated there. The mosaic floor was laid in the 4th or 5th century AD, when the villa was converted into a basilica. It has been conserved and stabilised to make it one of the few mosaics in Albania that can be viewed in situ by the general public.

The mosaic site is slightly to the south of Rruga e Durrësit, just inside the ring road (Unaza). It is hidden among residential buildings and is a little tricky to find, although it is signposted from the ring road. It should take about 15 minutes to walk there from Skanderbeg Square, or you could board any of the buses that go from the centre to the Zogu i Zi roundabout.

Statues and cemeteries

Tirana has several good examples of Socialist Realist statues, apart from those in and behind the National Gallery of Arts. The monument to the Unknown Partisan stands in a little square beside the junction of Xhorxh W Bush and Luigj Gurakuqi. The partisan rises above the people and the traffic, waving his comrades on into battle with one hand and gripping his rifle in the other. In the Lake Park, there is a charming statue of a partisan girl offering water to a soldier. Most imposing of all is Mother Albania, who overlooks the city at the Martyrs’ Cemetery (Varreza e Dëshmorëve. A flight of steps on the left of the path leads up to the parvis where Mother Albania stands, clutching a laurel wreath with a star and looking out over Tirana spread below her.

The Martyrs’ Cemetery is a long and, until you get to the Palace of the Brigades, not particularly interesting walk from the city centre. Any bus that shows ‘TEG’ as its destination will let passengers off and pick them up at the nearest stop to the gates (TEG is Tirana East Gate, the huge shopping mall at the junction of the Elbasani road and the new Tirana bypass). A taxi from the city centre would take between 15 and 45 minutes, depending on how bad the traffic congestion is.

Sharra Cemetery (Varreza e Sharrës) is just off Rruga Konferenca e Pezës, in the southwestern outskirts of Tirana. The turn-off uphill to the cemetery can easily be identified by the flower stalls just before it. The graves are grouped chronologically, but you need to bear in mind that Hoxha’s coffin was exhumed and reburied in 1992, and so that is his chronological position, rather than the date of his death, 1985. Once you are in roughly the right section, the large brown marble headstone is easy to spot; there may be fresh flowers on the grave. Mehmet Shehu, Albania’s prime minister until his fall from grace in 1981, has also been reinterred in the main cemetery.

Tirana’s parks

The relentless pace of construction over the last decade or so has meant the loss of many of Tirana’s green spaces, but two of the city’s best-loved parks have survived: they were known in the communist era as the Youth Park (Parku i Rinisë) and the Big Park (Parku i Madh).

In fine weather, Youth Park fills with people of all ages, relaxing with their friends or family. A massive monument to Albania’s centenary of independence, set in a pool whose water then flows through the upper section of the park, stands at the corner where the Boulevard meets Rruga Myslym Shyri. The large building on the opposite side of the park – facing on to Rruga Ibrahim Rugova – is a recreation complex known as ‘Taiwan’ (albanicised as ‘Tajvani’), in honour of the country that donated the splendid fountains beside it. The park was re-landscaped in 2019–20; an information panel indicates the intended purpose of each of its new sections.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Albania:

Related articles

This isn’t one for claustrophobes.

Boasting a number of UNESCO protected sites, Albania is home to a wealth of historic treasures.

Travel back in time with a visit to these important historical sites.