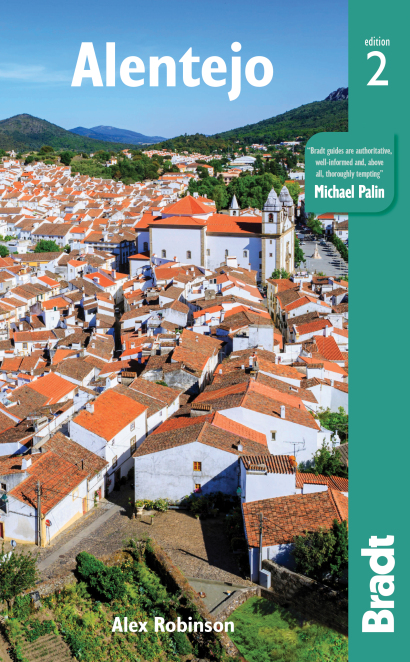

The cobbled streets that wind through whitewashed little towns and villages are lined with locally owned small shops where produce is made mostly by hand to centuries-old traditions.

Alex Robinson, author of Alentejo: the Bradt Guide

The Alentejo is Andalucía as it used to be. Crumbling Moorish castles sit perched on craggy hilltops. Tiny towns of cobbled streets cluster around ruined Roman temples or Renaissance palaces filled with priceless art. Eagles soar over rugged, rocky hills. Lynx hunt in forests of wild olive and cork oak. And on the coast hundreds of kilometres of sweeping caster-sugar sand see more visiting terns than tourists.

It’s hard to understand why few people choose to holiday here. The food and wine are as tasty as in Tuscany, the hill-walking as fabulous as any in France.

There are two UNESCO World Heritage Sites – the old Moorish capital of Évora, topped by a temple built by a Caesar, and the dramatic fortress town of Elvas whose winding, whitewashed Arab alleys and Baroque bell towers cluster around a castle within massive star-shaped walls. There are hotels fit for a king, quite literally: half a dozen of them sit within refurbished medieval mansions or castles where monarchs made their homes or talked over treaties that sealed the borders of early Europe.

The Alentejo is cheap, too – a fraction of the cost of neighbouring Spain. According to a 2015 survey the Alentejo is better day-to-day value even than traditional backpacker destinations like Bali. And frequent low-cost flights will whisk you into Lisbon and Faro (an hour’s drive away) for the price of cross-channel ferry.

Yet for now life in the Alentejo rolls along at a dreamy pace: wild boar bask in the herb-scented maquis, old men snooze outside white-washed cottages, and butterflies and bees buzz over acres of wild flower-filled meadows. And tourists who do arrive are welcomed as a curiosity.

For more information, check out our guide to Alentejo

Food and drink in Alentejo

Food

Most restaurants in the Alentejo offer Portuguese or regional dishes; international food can be hard to come by. But the Alentejo – which is known as the breadbasket of Portugal – is one of Europe’s undiscovered culinary destinations, with a strong regional cuisine and some of Europe’s finest wines. Alentejan food has more verve than most Portuguese fare, with a bolder use of herbs like coriander and a broad array of dishes. Dishes are full and strong flavoured, and are served in generous portions. Vegetarian options can be hard to come by.

Alentejo cuisine developed out of local resources. With fertile soils, the region has been used for growing olives, vines, cork, wheat and barley since Roman times. Acorns form the cork and holm oaks, grains and the thin grass growing on the plains and slopes provide animal fodder for sheep, some cows and pigs, including the uniquely Alentejan black pigs that forage semi-wild. The Alentejo’s woodlands, pastures and river valleys are home to game, including wild boar (javali), hare, partridge, quail and deer. The meadows are rich with wild herbs and gardens grow bushes of scented rosemary, thyme and lavender, alongside the reddest, plumpest tomatoes you’ll ever see.

The Alentejo is renowned in Portugal for its olive oil and bread, its goat and lamb and – perhaps most conspicuously – its pork. Many products are prepared from Alentejan pork or lamb. The presunto (cured ham) is as fine as Spanish jamón serrano or Italian Parma ham. Chouriço sausages are flavoured with the herbaceous fodder and nutty acorns upon which the black pigs graze. Dishes are rich and flavoursome, designed for feeding workers on the land. Other dishes are served with thick bready sauces, such as migas (made from fresh olive oil, breadcrumbs and herbs) or açorda (a garlicky bread-thickened, cilantro-infused soup served so hot that the eggs broken into it poach on contact). In the hills locals harvest chestnuts in autumn that are used to flavour soups and game dishes.

Towns and villages like Serpa, Niza and Évora are famous for their creamy sheep’s milk cheeses. Queijo da serra is sweet, soft and delicious as an appetiser. Queijo de Évora is a stronger, more mature cheese, with a mouth-wateringly peppery taste that goes well with a rich Alentejo red. Queijo de Serpa is the best of the lot – rich and creamy with a full, nutty flavour. On the coast the seafood is as fresh as you’ll find anywhere in Europe and it comes in great variety. Dishes include ameijoas à bulhão pato (clams in white wine and fresh herbs), arroz de lingueirão (a kind of risotto stew made with razor clams), choco (cuttlefish), delicately flavoured dourada (gilthead bream), and white fish like pescada (hake) and robalo (bass).

And then there are the convent desserts made in every other small town or village from recipes invented in the convents and monasteries. Such delicacies include encharcada (sweet chestnut mousses made from sieved egg yolks swirled into a skillet of boiling sugar syrup), elvas da sericaia (baked on a traditional tin plate and served with ripe plums), or pão de rala, a cake made with almonds and pumpkin, first made by the nuns of St Helena do Monte Calvário.

Drink

The Alentejo has some superb, inexpensive wines – from crisp, light whites that soften the summer heat to hearty, full-bodied reds for washing down those gamey autumn and winter dishes or sipping with a Serpa cheese.

Portugal has the second largest number of indigenous grape varieties in the world, many of which are grown in the Alentejo, and which impart their distinctive, regional character to the wines. They include Antão Vaz (perhaps the best white grape in the region, with good acidity and tropical fruit flavours), white Diagalves, Aragonez (aka Tempranillo, the most widely planted red), Alfrocheiro, Castelão and Trincadeira. Blends are common, and one of the commonest is of Aragonez, Castelão and Trincadeira – producing a deep, fruity red.

Health and safety in Alentejo

Health

There are no serious health issues to worry about, and no endemic diseases. Insect bites are perhaps the biggest risk in rural areas so it is worth taking an insect repellent. It is wise to be up to date with the standard UK vaccinations including diphtheria, tetanus and polio which comes as an all-in-one vaccination (Revaxis), which lasts for ten years.

If you do have an accident or fall ill, the level of healthcare is on a par with much of the rest of Europe. Residents of EU countries including the UK and Ireland should obtain a European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) before travelling, as this covers the costs of any standard medical treatment you may require. Everyone, including holders of an EHIC, should also take out travel insurance that includes medical costs, as the EHIC doesn’t cover all eventualities, such as repatriation to your home country following an accident. This is available in the UK by calling 0845 606 2030, or online at https://www.nhs.uk/using-the-nhs/healthcare-abroad/apply-for-a-free-ehic-european-health-insurance-card/.

Emergency care

In a medical emergency, dial 112 to call for an ambulance. The major hospital in the region is the Hospital da Misericórdia in Évora.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available at www.istm.org. For other journey preparation information, consult www.travelhealthpro.org.uk (UK) or https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ (US). Information about various medications may be found on www.netdoctor.co.uk/travel. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Portugal is a safe country with low crime rates. Pickpocketing and theft from cars occur in the more heavily visited areas. Be especially vigilant on public transport at the airport and at the busy railway station in Lisbon. If you must leave items unattended in a car, then be sure to hide them in the boot. Hire cars and foreign-registered cars are often targeted by thieves.

If your passport is stolen, report it immediately to the local police. You will need the report for insurance purposes and to obtain a replacement travel document from the British Consulate.

Female travellers

Portugal is a safe country for women travellers. Adopt the same common sense principles you would at home: avoid empty streets late at night and watch out for being followed; keep doors and windows closed and locked when you sleep; beware of accepting invitations from people you are not certain you can trust; and let people know of your whereabouts if you go hiking or on a trip.

Travelling with a disability

Facilities for travellers with disabilities in Portugal are similar to those in the UK or USA. Lisbon and Faro airports have disabled toilets and can provide special wheelchair assistance by prior arrangement. Transport vehicles have specially reserved seats for disabled people, but few have wheelchair spaces. The Cartão de Deficiente – Caminhos do Ferro Portuguesas (CP Disability Rail Cards) can be obtained from CP ticket offices and are valid for two years. They entitle cardholders to a 25% discount on services run by the state railway operator CP. Forms to apply for a CP card for the disabled are available from ticket offices. The applicant will need to supply two passport-sized colour photos and a disability card valid within the EU.

UK Blue Badge drivers can use their permits in Portugal and while there are no roadside concessions, some car parks allow vehicles displaying a Blue Badge to park free of charge. Disabled spaces in car parks are marked with a wheelchair symbol. Avoid those that are also marked with a registration number. It is worth leaving a piece of paper next to your Blue Badge with the following translation printed out:

Cartão de estacionamento para pessoas com deficiência. Este cartão autoriza o portador a beneficiar das facilidades de estacionamento no Estado membro no qual o titular se encontre. Quando em utilização, o cartão deve ser colocado no interior do veículo, no seu vidro dianteiro, por forma a que fique visível. Modelo da Comunidade Europeia.

Some hotels and public buildings have disabled toilets and access ramps.

LGBTQ+ travellers

In southern Europe Portugal is perhaps the country most tolerant of gay and lesbian travellers. Legislation is some of the most tolerant in the world. Same-sex marriage was recognised in 2010 and there are wide-ranging anti-discrimination laws. World Rainbow Hotels and Purple Roofs list gay- and lesbian-owned and friendly accommodation in Portugal and gay- and lesbian-friendly travel agents and tour operators.

Travelling with kids

Travel with children is straightforward in Portugal. Portugal is a very family-orientated country and kids are never expected to be seen but not heard. Even expensive restaurants provide children’s seats and most have children’s menus. Many hotels offer a discount family rate, don’t charge for children under five and can provide an extra camp bed for a double room. Children under three generally travel for 10% on internal flights and for 70% until 12 years old. On tours children under six usually go free, and it may be possible to negotiate a discount rate. Bring Kwells or Stugeron from Europe or the US for motion sickness.

Travel and visas in Alentejo

Visas

Citizens from EU countries, the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, Israel, South Korea, Argentina and Brazil do not require visas to enter Portugal. Nationals of Australia, Canada and the USA can stay for up to 90 days without a visa. EU nationals can stay for an unlimited period, but must register with the local authorities after three months. After the UK leaves the European Union, documentation requirements for UK citizens may change. Check before travelling.

Getting there and away

The Alentejo is easy to reach. Lisbon is served by regular direct international flights with TAP from destinations in North and South America, Asia and European capitals. Australasians will need to change planes in London or another European capital. There are flights into Faro from UK, German and Irish airports, and Badajoz in Spain (which is just 15km from Elvas) has connections to other destinations in Spain.

Lisbon airport has car rental offices on the ground floor of Arrivals. Buses 208 and 705 connect the airport to the Estação Oriente railway station for trains to Évora and Beja. Badajoz Airport has connections only with other cities in Spain and is linked to Évora and Elvas by regular buses. There are car rental booths in Faro Airport but no buses from the airport to the Alentejo. You will need to take a taxi to Faro bus station, from where there are onward connections to cities in the Alentejo.

Getting around

By bus

The Alentejo has an extensive intercity and local bus network. Intercity buses are run by Rede Expressos, whose site has timetable and price information in English. Local buses run on weekdays only, on an extensive network that covers even the smallest villages. Information is available from Rodoviária do Alentejo. The website, while in Portuguese only, is easy to use. Click ‘Ver Horarios’ to see PDFs of timetables. Bus prices are less than half their equivalent in the UK for a similar level of comfort. Some buses have toilets.

By train

Évora, Alcáçovas, Alvito, Cuba and Beja are connected to Lisbon’s Oriente station by four intercidade (intercity) trains daily. For information contact Comboios de Portugal. Tickets are available through travel agents or in railway stations and do not need to be booked in advance except on public holidays. First class (primeira/conforto) is more spacious with better seating and more storage space than second class (segunda/turística). Fares are low, with a ticket between Lisbon and Évora costing around €17 one way/€30 return in first class and around €13 one way/€22 return in second class.

By car

The best way to get around the Alentejo is by car, as this affords access to the smaller villages, the beaches, and out-of-the-way castles and natural attractions. Portuguese roads are excellent and far emptier than those in the UK. Motorways have toll booths, so be sure to carry loose change with you. Streets in Alentejo towns were built for people or horses by the Moors and can be very narrow. Avoid driving in town centres if possible.

With 62 road traffic deaths per 1,000,000 in 2017, Portugal is higher than the EU average, but safer for drivers than Romania (with 98), but less safe than the UK (with 27). Drive on the right-hand side of the road, giving way to the left at roundabouts. Speed limits are 120km/h on motorways, 90–100km/h on highways, 30–50km/h in towns. The legal alcohol limit when driving is 0.05mg.

Child safety restraints are mandatory for all children up to 12 and under a height of 1.5m, who are permitted to travel in the front seat only if the proper restraints are in place and the airbags switched off. Cars with no seat belts in the back seats can’t carry children under three years old.

It is mandatory to carry your driving licence, vehicle registration document (V5) and certificate of motor insurance. Fines have to be paid on the spot; most police vehicles have a portable credit/debit card machine. Failure to pay on the spot will result in the retention initially of the documents (for which you will receive a receipt), and if the fine is not paid in three days, of the vehicle.

Car hire

Rental costs with unlimited mileage start at around €50 per week and are often cheaper midweek off season when booked ahead online. The major players all work in Portugal and have offices in the airport at Lisbon, which is the best place to hire for choice and prices. There are also car rental offices in Évora and Beja.

When to visit Alentejo

The Alentejo is best visited in spring, late summer and early autumn when temperature is in the 20s and low 30s and visitor numbers are at a minimum. Spring sees the meadows burst into multi-coloured bloom, storks nesting on telegraph poles and butterflies on the wing. In autumn the vines and olive trees are heavy with fruit, the leaves are beginning to turn golden brown and wispy mist floats over the Serra de São Mamede mountains. Wildlife lovers – especially birdwatchers – should also consider winter, when huge flocks of migrating birds arrive on the coast and around the lakes.

Climate

The Alentejo has a Mediterranean climate with hot (and occasionally very hot), dry summers, mild autumns and winters (with changeable, rainy weather and snow only in the Serra de São Mamede mountains), and warm, sunny springs.

What to see and do in Alentejo

Capela dos Ossos

If the Carmelite Church focuses on the spiritual, then its Franciscan counterpart is grimly material, built in the 17th century when the Inquisition was at the height of its powers and punishments, and executions must have been a frequent occurrence in the nearby Praça do Giraldo. ‘We bones wait here for yours to join us’ reads the inscription over the chapel. Thousands are squeezed into the walls of the building, yellowing in the frowsty air. It’s hard to know what’s more horrible – the chapel itself or visions of it being built. One imagines the friars with a huge pile of remains in the middle of floor, arranging them neatly by size, fitting them into the gaps in the wall like pieces of a puzzle – a femur here, a tibia there, a small skull squeezed into the last small space between the top of a column and the ceiling.

Popular mythology has it that the monks were trying to solve an overcrowding problem at the city’s monastic cemeteries and that the bones are all of the clergy. In reality the friars robbed graveyards throughout the city, exhuming the dead from the city’s cemeteries in a quest for morbid masonry. By the time they had finished their work the monks had consumed some 5,000 skeletons and were, it seems, so inured to death that they hung two desiccated corpses – one of them of a child – from the chapel walls for extra shock factor. A popular legend has it that they are the corpses of an adulterous husband and his son, cursed never to rot to bones by the betrayed wife on her deathbed.

Castelo de Marvão

There can be few castles anywhere with a better strategic position than Marvão’s. The fortifications seem to grow out of the rock, the walls perched on the edge of a ridge as it ascends to a peak affording 360° views running to scores of kilometres in every direction. In 1758, when Marvão’s fort had reached its greatest proportions, the Portuguese chronicler Frei Miguel Viegas Bravo described the castle as ‘the most unconquerable in the entire kingdom… whose walls serve more for preventing those inside from falling than those outside from entering.’

Like most Alentejo castles, Marvão’s is a composite building – walls upon walls, beginning with stones first assembled here before the Romans came. While some of the gates to the castle appear to be Roman in origin, the first great fort was built by Ibn Maruán, with many of the stones taken from the ruins of Ammaia. The castle keep and the walls were strengthened under the orders of Dom Dinis, who constructed an enormous cistern big enough to hold six months’ worth of water for the entire town population in the event of a siege.

Castelo de Vide

With sugar-white cottages, coloured pink and violet with hanging flower boxes and tumbling down a steep hill from a massive crusader castle, Castelo de Vide is one of the Alentejo’s prettiest towns. Old widows wander the cobbles, men in cloth caps gather to chat idly on street corners and cats ooze out of open windows, with a stretch and a yawn, to lollop and laze in the sun.

Spring and summer late afternoons are particularly beautiful, after the monuments and museums close and Castelo de Vide returns to being a tiny provincial town, bathed in light as yellow and warm as melting butter and drifting into slow, sedate sleepiness. The views are lovely – terracotta roofs against the meadows and vineyards of the plain, furrowed with shadows by the sloping sunlight, the curves of medieval terraced houses rising to battlements or dropping to bell towers, the mantled coronet of Marvão’s walls on a distant ridge. Around the castle meadow, butterflies fill the air like floating petals and in the narrow alleys of the ancient Jewish quarter the scent of dinner drifts out from half-open shutters.

Cromleque dos Almendres

Together with the cromlech of Vale de Maria do Meio and the Zamnujeira megalithic site, this group of mostly Neolithic monuments are the most significant in the Iberian Peninsula and rank among the most important prehistoric remains west of the Pyrenees.

Almendres Cromlech is one of the oldest and biggest stone circles in the world – with construction beginning around 6,000BC and continuing through to the structure you see today, which dates from around 3,000 years later. Almendres and the other monuments nearby are the best known of a scattering of some dozen stone circles and 800 menhirs in the Évora region – testament to the area’s large population in prehistoric times. The monuments are of probable astronomical significance. Évora is situated on one of only two latitudes in the world where the full moon appears on the zenith on certain nights of the year.

The more famous and impressive Cromeleque dos Almendres (Almendres Cromlech, or ‘Cromlech of the Almonds’) is a huddle of more than 20 stones, smoothed into concaves by millennia and clustered in a cork oak grove on a hill, also looking out towards Évora. They look like spectral, shrouded children, frozen in time. Try to come during the week early or late in the day when the site is empty, the breeze plays in the trees and the grove is imbued with a sense of the sacred.

Évora

Nowhere in the Alentejo is more redolent with history than its capital, Évora. Rising in narrow, winding Moorish streets to a central praça, crowned with a magnificent ruined Roman temple, ringing with the peal of bells from an array of Portuguese Golden Age churches and littered with stately mansions and monuments, the city has been protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986. Its listing as such owes as much to its architectural unity as it does to its magnificent churches and small museums, for while Lisbon was levelled by the 1755 earthquake, Évora retains its medieval and Renaissance buildings. Nowhere in Portugal better preserves the country’s architecture of Empire.

Évora is large enough to lose yourself in over a long summer day – idly wandering the cobbles, pausing to visit the Roman Temple, the cavernous cathedral and the beautiful churches of the Convento do Carmo and the Igreja de São Francisco (with its grisly chapel of bones). There are myriad fine restaurants dishing up traditional cooking from the area and cafés and bakeries serving local cakes, cheeses and wonderful coffee. The shopping is the best in the region – not just for souvenirs, but for everyday items like shoes, clothes and hats, which are so much better value in Portugal than back home, and for fine food and drink, including wonderful Alentejo wine.

But Évora is more than a historic monument. It is a bustling community too. And while many of the smaller villages in the Alentejo feel abandoned by the younger generation, Évora is eternally youthful, its streets rejuvenated annually by the arrival of fresh batches of students rushing to attend lectures at the Alentejo’s biggest university, gathering to gossip under the arcade in the Praça do Giraldo and nursing weekend hangovers over over a late breakfast in one of the numerous cafés.

What to see and do in Évora

Capela dos Ossos

‘We bones wait here for yours to join us’ reads the inscription over the Chapel of Bones. Thousands are squeezed into the walls of the building, yellowing in the frowsty air. It’s hard to know what’s more horrible – the chapel itself or visions of it being built. One imagines the friars with a huge pile of remains in the middle of floor, arranging them neatly by size, fitting them into the gaps in the wall like pieces of a puzzle – a femur here, a tibia there, a small skull squeezed into the last small space between the top of a column and the ceiling.

Popular mythology has it that the monks were trying to solve an overcrowding problem at the city’s monastic cemeteries and that the bones are all of the clergy. In reality, the friars robbed graveyards throughout the city, exhuming the dead from the city’s cemeteries in a quest for morbid masonry. By the time they had finished their work, the monks had consumed some 5,000 skeletons and were, it seems, so inured to death that they hung two desiccated corpses – one of them of a child – from the chapel walls for extra shock factor. A popular legend has it that they are the corpses of an adulterous husband and his son, cursed never to rot to bones by the betrayed wife on her deathbed.

Templo Romano

With dark Corinthian columns stark against the sky, the Roman Temple is the only significant remnant of the old Roman settlement of Ebora. It once stood on one edge of the main public square, or forum, which would have served as the Roman town’s principal meeting place and market.

The building you see today is not original, but is rather a romantic reconstruction built in the late 19th century by the Italian architect Giuseppe Cinatti. Archaeologists have had to piece together clues as to the building’s origin and purpose from its parts rather than Cinatti’s whole.

Sé (Évora Cathedral)

A vast stone hulk, Évora’s cathedral inelegantly fuses Romanesque, Gothic and Baroque. Its massive masonry and squat pinnacled lantern tower dominate the sky. It looks like a refuge in the shape of a church, built by a despot to fortify himself against any conceivable onslaught. And in essence this is what it was.

When work began on the building, the prevailing architectural style was Romanesque. The side façades, cavernous, top-heavy lantern tower and huge, frowsty nave (with its massive, rounded rose granite arches) are in this style. The expansive cloisters (with Manueline flourishes and sculptures of the Evangelists), rose windows and entrance portico are later Gothic. The last is particularly impressive – extending in six marble arches over corbels decorated with effigies of the apostles standing over rows of human and fantastical animal figures.

Igrejo do Carmo

This is the most peaceful and little-visited churches in the city. Entrance is through an impressive Manueline doorway made up of carved ropes and knots and transposed from an original Manueline Braganza palace destroyed in a fire in the 17th century.

The church interior has been largely renovated in recent years. The expansive, airy nave is flanked by chapels with towering gilt altarpieces which rank among the best in the city and whose exuberant carving seems inspired by the hope of Resurrection rather than the gloom of crucifixion and death so often expressed in Baroque church art in Iberia.

The city walls

Évora has two sets of city walls – one dating from Roman times, the other from the late Renaissance. Remnants of both still exist. The most impressive remnants of the early wall are the Porta de Dona Isabel, a very well-preserved Roman arch, and the Torre de Sisebuto, where bits of Roman wall are visible, together with the exposed ruins of a 1st century AD Roman house with simple glazed frescoes.

The city’s outer walls, which are still largely intact in a number of places – most notably around the Porta da Lagoa gate – date from between the Middle Ages and the 17th century. Évora’s aqueduct bisects the 17th-century walls between the Porta da Lagoa and the Porta de Avis gates in the city’s north. It was built on

the site of an earlier Roman construction, and dates from the early 16th century. A walking or bike trail follows its path, beginning on Rua Cândido Mendes and continuing for 8.5km past the 17th-century Forte de Santo António to Metrogos, from where it is possible to catch a taxi back to Évora.

Grândola

While it has no standout attractions, the provincial town of Grândola is perfectly situated and well appointed with hotels and restaurants, making it the best beach as a base for exploration of any location on the central or northern Alentejo coast. There are sweeping stretches of sand on the doorstep, and lovely rolling cork-covered countryside. Tróia’s least spoilt beaches are 15 minutes’ north, while the Lagoas de Santo André e da Sancha wildlife reserve and the Roman ruins of Miróbriga are just 20 minutes’ drive south. Beyond these, the Alentejo coast grows ugly and industrialised for a bit around Sines, the site of one of Iberia’s largest and smelliest oil refineries; it is recommended you avoid this area.

In Portugal this sleepy town is famous for being emblematic of the Alentejo’s stalwart socialist spirit. In the early 1970s the town was immortalised as ‘Grândola, Vila Morena’ in a song in the Cante Alentejano form by the Bob Dylan of Portugal, the poet and folk singer Zeca Afonso, who was strongly censured under the Salazar regime. Afonso used the townspeople as symbolic of the Portuguese fraternal spirit which stood in opposition to Salazar’s fascist regime. ‘Terra da fraternidade Grândola, vila morena, Em cada rosto igualdade, O povo é quem mais ordena’ he sung – ‘Land of brotherhood, Grândola, the sun-burned town with equality in every face, where it’s the people who give the orders’. The song was broadcast in 1974 by the Portuguese radio station Radio Renascença as the signal for the upsurge that became the Carnation Revolution. There’s an iron monument in homage to the singer outside the town hall. It’s about the only sight of interest in the town itself; Grândola, while pleasant enough, is not a destination in its own right, but it is nonetheless the best place to base yourself along the central and northern coast, positioned for easy access to the beaches north to Tróia and south to Sines. The wetlands and meadows around the Santo André lagoon and the Roman ruins at Miróbriga are on the doorstep, and Grândola boasts some of the best rural hotels and restaurants on the Alentejo coast.

Mértola

Clambering in a clutter of terracotta roofs and whitewash up a steep hill on the banks of the sinuous and sluggish Guadiana River, and surrounded by a natural park, is the prettiest of the Baixo Alentejo’s Moorish towns. And as it’s in easy coach reach of the Algarve, it’s one of the region’s most visited. The town has a long and noble history, but aside from an excellent museum of Islamic art and a fascinating old church built into an original Moorish mosque, there are no outstanding attractions. Like Castelo de Vide in the north, Mértola is a place in which to base yourself, or to visit on a long, languid summer afternoon to soak up the atmosphere and sip a beer or coffee while gazing out over the river.

Monsaraz

Ringed by a perfectly preserved medieval wall, criss-crossed with cobbled streets and with whitewashed bell towers brilliant under the burning sun, Monsaraz is the kind of fortified hill town that should come with an Ennio Morricone soundtrack. It’s all about atmosphere here. Try and come early, off-season and on a bright sunny day, when it’s so quiet that your footfalls echo along the streets and you can hear the braying of donkeys kilometres away across the plain. There are no outstanding sights; Monsaraz itself is the destination. And the views of the tiny town are the reason for coming here: from below, looking up at its rocky hill; from its highest point, white against the golden plain; and from its castle battlements out over the Alqueva Lake and the grasslands of the high Alentejo.

Monsaraz is 18km east of Reguengos de Monsaraz, its modern counterpart and a provincial olive-, sheep- and wine-producing town with no sights of real interest. There are dozens of prehistoric ruins in the surrounding countryside and a few wineries open for visits.

Parque Natural da Serra de São Mamede

North of Arronches the Alentejo’s plains become increasingly mountainous – the flat lands give way to low hills and then rugged country where rolling moors replace the plains, and crags become rocky ridges whose lower slopes are covered in woodlands of wild hazel, pine and oak perfumed with wild sage and interspersed with meadows of rock roses, silene, periwinkle and pimpernel. Prehistoric relics dot the fields – dolmens like crooked tables, the clustered circles of cromlechs and menhirs pointing skyward. Rivers and streams ripple through the hills and two big lakes dominate the lowlands, forming important havens for endemic amphibians and reptiles, as well as migratory water birds. Roads wind into the hills, to peaks and escarpments, some crowned with fortress towns like Marvão, Alegrete and Castelo de Vide, others bare and circled by soaring raptors. The land rises to the highest peak in southern Portugal, the Pico de São Mamede.

Most of the area is protected as the Serra de São Mamede Natural Park. It is contiguous with the Parque Natural do Tejo and links with the ZEPA Sierra de San Pedro to form one of the largest protected areas in southern Iberia and an important refuge for otter, wildcat and Cabrera’s vole, which is on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list. The disused Cova da Moura mine has one of the largest bat colonies in Europe and the Serra has more reptile and amphibian species than anywhere else in Portugal, including the brilliant green emerald lizard, and European and Spanish pond turtles. But it is the birds that make the Serra truly spectacular, with some 150 recorded species, including big spectacular birds like Bonelli’s eagles, as well as Spanish imperial and short-toed eagles and black and griffon vultures, which are particularly abundant in the south of the park near Arronches and in the north of the region around the Tagus.

With its hilltop castles – like Marvão – this is one of the few places in Europe where you can see raptors from above as they soar. Other rare species seen in the area include stone curlew, scops owl, purple swamp hen, azure-winged magpie, black stork, lesser kestrel, red kite, great and little bustards, great spotted cuckoo, roller, azure-winged magpie, rock bunting, black wheatear and Spanish sparrow.

The park has good hiking and mountain biking with myriad opportunities for day walks or rides and longer treks, including walking from village to village. As elsewhere in the Alentejo, there are many rural homestays whose owners can help with orientation.

Rota Vicentina coastal trail

The Rota Vicentina is one of Europe’s most spectacular coastal paths, running along deserted beaches, craggy cliff tops and riverbanks, through meadows bursting with wild flowers, cork oak and pine forests and herb-scented maquis, and cutting through a string of magical little villages along the way. Almost all of the route lies within the Alentejano e Costa Vicentina Nature Reserve, a 200km-long chunk of protected shoreline.

The route takes in all of the Alentejo and western Algarve coast between Santiago do Cacém in the north and Cabo São Vicente (Cape St Vincent) – mainland Europe’s westernmost point – in the south. Within the Alentejo there are two possible starting points.

The most popular route is the 120km Fisherman’s Trail, which takes in the best stretches of the beautiful Alentejo coast and begins in Porto Côvo. From here the path hugs the coast south through Vila Nova de Milfontes, where you can take the ferry across the River Mira, south to Almograve and Zambujeira do Mar. The path continues along the shoreline from here to Odeceixe, after which it cuts inland, running parallel to the coast through the Algarve. Where the path is forced to cut inland there are circular loops around some of the prettiest coastal stretches. It eventually reaches Cabo São Vicente.

An alternative route, the 230km Historical Way, begins in Santiago do Cacém further north, running inland through the hills to Odemira, then crossing the River Mira and joining the Porto Côvo route at Odeceixe.

Vila Viçosa

Today Vila Viçosa is a sleepy, unassuming little marble-producing town whose pretty streets are lined with orange trees. But between the 13th and 19th centuries it was one of the most important locations in the Alentejo, as the site of an imposing castle and a magnificent ducal palace, both built by the powerful Braganza dynasty, whose scions sat on the thrones of Portugal and England. Both their castle and their palace can be visited today.

Visit the birthplace of Catherine of Braganza

Popular belief in England has it that Catherine of Braganza was a poor choice of wife for Charles II – dowdy, unsophisticated and ill-equipped to deal with life at the brilliant English court. The truth is entirely the opposite. Catherine was a trendsetter who changed England more than any other consort queen. As the daughter of João IV, king of a new and independent Portugal, she came from a court with refined European tastes. The English monarchy, by contrast, was severely damaged, near bankruptcy and culturally decades behind contemporaneous Europe. Catherine’s dowry replenished the coffers and included the Bombay islands and free trade with the Portuguese colonies, among them India and gold-rich Brazil. And the new queen introduced tea (then a luxurious drink almost unknown in England), marmalade (originally quince jelly in Catherine’s court) and the use of forks rather than just knives at the dinner table. She also brought European dancing and a trend for wearing trousers and shorter skirts (the robust women of Charles II’s court were famously jealous of Catherine’s slim legs and ankles). After installing herself in Somerset House she introduced modern European music too, through the appointment Giovanni Baptista Draghi (an important influence on Henry Purcell) as the master of music in her chapel. By the 1680s Italian opera had become the most fashionable music in London. Despite her forbearance, Catherine was treated deplorably by Charles, who had 14 children by his various mistresses, one of whom she was forced to accept as her servant – the heavy-set, Rubenesque Barbara Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine, described by contemporaneous writer John Evelyn as the ‘curse of the nation’.

Yet Catherine is remembered unfavourably. This is largely because she was hated by the women of Charles’s immoral court. Furious that the queen disapproved of the immorality of the court, Charles’s myriad mistresses and Machiavellian courtiers desperately tried to persuade the king to divorce her, fabricating stories of her treachery. He repeatedly refused. So they resorted to portraying her as dull and dowdy, and her reputation only began to improve after the publication of an early 20th-century biography by the American historian Lillias Campbell Davidson, who famously wrote that: ‘Catherine lived in her husband’s court as Lot lived in Sodom. She did justly, and loved mercy, and walked humbly with her God in the midst of a seething corruption and iniquity only equalled, perhaps, in the history of Imperial Rome.’

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Alentejo:

Related articles

The Portuguese are wise; they keep the best for themselves.

There are many national parks in Europe that remain fairly unknown. Here you can discover 14 of the best. Why miss out on visiting somewhere spectacular?