Bulgaria’s attractions for visitors have grown both in number and diversity. Food and wines are delicious and affordable. Museums, churches and monasteries are a window into Bulgaria’s rich and turbulent history.

Annie Kay, author of Bulgaria: The Bradt Guide

It might be a cliché, but in Bulgaria there really is something for everyone. The question is: where to start?

Perhaps with the capital, Sofia – the perfect destination for a relaxing city break. The centre is compact and can easily be covered on foot at a gentle pace in a couple of days, even allowing for coffee and lunch breaks. There are some familiar fast-food and retail outlets, but there is also an eclectic mix of Viennese-style boulevards, monumental set-piece official buildings from the communist era and glorious gold-domed churches. The capital is very green with numerous parks, there are museums with recently unearthed treasures and a variety of colourful markets and stylish shops to discover. There are exciting new attractions, too: the Sofia History Museum, the new art gallery complex Kvadrat, and the excavated area of Ancient Serdika.

Outside Sofia there are several other rewarding towns and cities, such as Plovdiv, with its UNESCO-listed Old Town, and Veliko Turnovo, the former capital. The ski resorts of Bansko, Borovets and Pamporovo offer great skiing, great nightlife and great value. The Black Sea coast has fine beaches, watersports and nightclubs, but also quieter spots for family holidays, butterfly observation and birdwatching.

Rural Bulgaria has changed too in recent years: many young people have left for the cities or abroad, leaving an increasingly elderly population to work the land. However, investment in wineries, ecotourism and activity holidays should gradually attract more people back to the countryside. It is a wonderful place to drive; roads are quiet, wildlife is rich, the mountain scenery is unrivalled and there are monasteries, archaeological sites, caves and rock formations, as well as picturesque villages and vineyards, to visit.

Bulgarians tell a nice story against themselves: God was dividing up the earth between all the different peoples; characteristically the Bulgarians arrived late and God had nothing left. So he gave them a piece of Paradise.

So, whether you are looking for mountains or monasteries, wine or walking, beaches or birds, Bulgaria really does cater for all your needs. Visit and you will be welcomed with open arms.

For more inforamtion, check out our guide to Bulgaria

Food and drink in Bulgaria

There are said to be three great cuisines in the world: French, Chinese and Turkish. Bulgarian cuisine is very similar to Turkish. Its strengths are the wonderfully tasty salads, vegetables, herbs and fruits. There are slow-cooked meat dishes, grilled meats and plenty of meat-free dishes based on eggs and cheese. Nowadays many vegetables are available all year round from imported sources, but if you stay with the local seasonal produce you’ll get the best flavours. For more information and illustrations, click here.

Often folk-style restaurants (mehanas) have a choice of dried herbs and spices on the table, to dip your bread in. Choubritsa (a Bulgarian dried herb), sharena sol(choubritsa and salt) and paprika are the usual ones. Herbs are frequently used in cooking; local ones include savory, parsley, dill, mint, paprika and basil. The dipping of bread in this way is part of a traditional welcome; indeed, some restaurants have a waiter outside greeting guests by offering bread and herbs.

Salads are arguably the best part of the meal. The most popular is Shopska salad, named after the Shops, the people from around Sofia. This is a mixture of chopped tomatoes, cucumber, onion and fresh or preserved peppers, sprinkled with grated or crumbled sirene cheese (made from sheep’s or cow’s milk, this is the Bulgarian version of feta, subtly different, and available now in the UK at Bulgarian grocery shops).

There are many types of salad, and also single-ingredient salads of just tomatoes or baked peppers, for example. Snezhanka is made from chopped cucumber in strained yoghurt with garlic and chopped walnuts added. In summer the popular tarator (a cold soup) is essentially the same ingredients in a more liquid form and it’s very refreshing. In winter try turshiya, made from pickled vegetables such as cauliflowers, carrots, peppers and green tomatoes. Kyopolou is made by roasting aubergines and peppers and mixing them, minus their skin, with garlic, parsley and oil.

Bulgarian yoghurt, or kiselo mlyako, meaning ‘sour milk’, is world famous. It has a long history: the Thracians were very good at stockbreeding and produced a number of dairy products, and the word yoghurt is believed to be from the Thracian language. In 1905 the secret of Bulgarian yoghurt, a special bacteria named Lactobacillus bulgaricus, was discovered. There are different varieties made from the milk of cows, sheep, goats and buffaloes, and blends of these. In Bulgaria, they are all used for the preparation of various healthy dishes such as tarator and ayran (the ultimate drink for thirsty people – a mixture of yoghurt, water and salt).

Bulgaria has a long historical connection with wine; there is evidence of viticulture and winemaking in Thracian times. Archaeologists have proved this theory with their numerous finds of stone troughs which were used for winemaking and ageing. The wines of Thrace are mentioned by Homer in both The Iliad and The Odyssey.

Under the post-war communist government, wine production was nationalised. Winemaking became an industry as massive wineries, supplied by huge new vineyards, dramatically increased production levels. During the 1960s a more scientific approach was adopted, as varieties of grape were more carefully matched to the areas that provided the best growing environment for them. At this time too the classic grapes (mainly French) were introduced with resounding success.

Bulgaria’s winemakers are still fascinated by experiments with new grape varieties, but often blend them with indigenous grapes. Some older, almost forgotten, varieties are being revived.

Health and safety in Bulgaria

Health

There are state-run hospitals, private medical centres and local polyclinics in Bulgaria. Doctors are extremely well qualified and able, but they are often let down by poor equipment and facilities. Nurses are efficient but often without the friendly, personal touch that makes hospital treatment bearable. You will not find many English speakers, so try to take a Bulgarian friend with you if you do need hospital treatment, or take advice from your embassy.

All travellers are entitled to free emergency medical and dental treatment, but must pay for medicines (tourists and Bulgarians pay a fixed fee: 6.10lv in 2020).

Citizens of European Union countries need to obtain a European Health Insurance Card (EHIC), which entitles you to medical treatment on the same terms as Bulgarian nationals, though this is not a substitute for comprehensive medical and travel insurance, which should also be arranged. In the UK the EHIC is obtainable online or from post offices using form T7. Once the UK fully leaves the European Union, documentation requirements for its citizens may change. Check before travelling.

All foreign visitors should have valid medical insurance for the length of their stay, especially since access to public hospitals is not always easy to arrange. The availability of private medical treatment is on the increase and it is not expensive for foreigners; keep your receipts if you intend to claim on your travel insurance. Every town will have several pharmacies (look for the sign ‘Аптека’). Most have familiar proprietary brands on sale and can offer advice and recommend a local polyclinic.

Safety

Bulgarians believe that crime is at a high level, though it is actually much lower than in the UK. Regarding general safety, be careful, but don’t be worried. Theft, particularly of cars, is the most common crime in cities, but very rare in the countryside. However, there are plenty of inexpensive secure car parks available in cities.

Obviously you should behave with reasonable caution, particularly in crowded places such as markets and bus and train stations, as you should in any country. Keep money and expensive belongings out of sight, wear a money belt, and have your handbag across your body rather than on the shoulder.

There have been reports of drivers being stopped by con men posing as policemen and being asked to pay on-the-spot fines. You should play dumb and ask to be taken to the police station to have someone translate what you have apparently done to break the law. Similarly, it is probably best to be cautious if someone tries to flag you down to help with a breakdown, or, in the case of single male travellers, to be cautious if a ‘damsel in distress’ tries to attract your attention.

Bulgaria regularly experiences earth tremors, normally minor, registering up to 4.5 on the Richter scale.

Female travellers

In Sofia and on the coast the dress code for women is much the same as elsewhere in Europe, but in rural areas people are more conservative and, if you plan to travel alone, you should undoubtedly dress to camouflage rather than impress. You will certainly be stared at and commented on or even propositioned, but a firm rejection should suffice. As always, it is much better to avoid awkward situations than to have to get out of them. Travel with friends, or join forces with another solo traveller, especially in potentially hazardous places like overnight sleepers on trains.

Foreign and local businesswomen are treated in the same way as their male colleagues. Generally you will find Bulgarian men gallant in a way we have become unused to in the UK, opening doors and seating you at the table, for example. In both the private and public sectors there are many successful Bulgarian women, though attitudes to women are in general a little more conservative than in the UK, particularly among the older generation.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Although homosexuality is no longer illegal, outside the main cities and resorts there is little tolerance towards gay people. Overt displays of affection and flamboyant dressing should probably be avoided.

Travelling with a disability

Travellers with a disability, particularly wheelchair users, will find Bulgaria difficult. Few places have disabled access, many pavements are in poor repair, and many of the attractive old towns have steep and/or cobbled streets. New buildings are obliged to provide suitable access, but until the roads and pavements leading to them are better, there will still be problems. Public transport such as trams and buses are not adapted for wheelchair users, or those with walking difficulties.

Specialist UK-based tour operators that offer trips to Bulgaria include: Enable Holidays, Disabled Holidays, and Disabled Access Holidays.

Travel and visas in Bulgaria

Visas

UK nationals who hold a UK passport endorsed ‘British Citizen’ do not need a visa to visit Bulgaria for a period of up to 90 days in a six-month period. Passports should be valid for the period of the intended stay. Other UK passport holders require a visa and a passport that is valid for at least six months. Once the UK fully leaves the European Union, documentation requirements for UK citizens may change. Check before travelling.

Irish and other EU nationals do not need a visa to visit Bulgaria for a period of up to 90 days within a six-month period. A passport valid for the period of intended stay is required. Citizens of the USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia do not need a visa to visit Bulgaria for a period of up to 90 days within a six-month period. Passports must be valid for at least three months after entry.

South Africans, however, do need a visa to enter Bulgaria. A passport valid for at least six months on entry is required and a visa will be issued only if blank pages are available.

Getting there and away

By air

The main international airport is Sofia Airport. Terminal 2 opened in 2007 and is for international scheduled services. Terminal 1 is used for domestic, budget and charter flights. The three other airports, Plovdiv, Varna and Burgas, mainly operate with charter and budget flights.

There are regular flights between Sofia and Alicante, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Berlin, Brussels, Cologne, London, Madrid, Malaga, Manchester, Milan, Moscow, Palma de Mallorca, Paris, Prague, Rome, Tel Aviv, Vienna and Zurich, as well as internal flights to and from Burgas and Varna. There are also international flights to Burgas and Varna, but these are mainly holiday charters and mainly in summer. However, the budget airline WizzAir flies to both coastal airports several times weekly all year round from Luton airport.

There are no direct flights from Australia, New Zealand or Canada, so travellers from there will need to connect via a European hub.

By train

There are trains from Belgrade, Bucharest, Istanbul, Munich, Thessalonika, Venice, Vienna, Zagreb and Zurich. From elsewhere in Europe you need to make a connection via these stations or along the route. Customs formalities and passport control are carried out on the train. For information and timetables, click here.

It is worth booking a sleeper, which is both the safest and most comfortable option. Tickets can be booked through any European rail agency. In Bulgaria, train tickets are sold by BDZ Passenger Services Ltd. International train tickets are sold in Sofia’s central railway station and in the central stations of 11 district towns.

By bus

Buses from all the major European cities run to Sofia, Plovdiv, Varna and Burgas. The biggest bus company is Eurolines, and from the UK there is also Balkan Horn.

By car

It is very convenient to have a car in Bulgaria for travelling around the country, as there is a well-developed network of roads, although some are in poor condition. It is, however, a long drive there, so, unless it is part of some extended travelling, it may be easier to hire a car on arrival.

There is a compulsory road tax, which takes the form of an electronic vignette, and costs 10lv for a weekend, 15lv for a week and 30lv for a month. These are available at the border and major service stations, click here for more information. To cross any of the borders, you’ll need your personal documents and those proving ownership of your car, or the contract for your hire car, plus insurance documents.

When to visit Bulgaria

Climate

Bulgaria is very diverse geographically, and this is reflected in the climate, which is quite extreme. It can be bitterly cold in winter and uncomfortably hot in the cities in summer. The southwest has higher temperatures in both summer and winter, as warm air from the Aegean arrives via the Struma Valley. Places such as the ski resort of Pamporovo in the southern part of the Rhodope Mountains are noted for their mild sunny winters. The coast is hot in summer, though with pleasant sea breezes, and is usually damp and often misty in winter, but snowfalls, even of significant amounts, are possible.

Sofia is frequently foggy in winter with below-zero temperatures by day and night common, while in summer it is hot and sunny. The area north of the Balkan Mountains on the Danube Plain can be particularly bleak in winter, whereas to the south of the same range the Valley of the Roses and Thracian Plain are protected from the worst of the cold weather coming from the north.

Bulgaria has something to offer all year round. In spring the towns and cities blossom as parks and gardens reawaken and outdoor eating at cafés and restaurants begins again. For nature lovers this is the most spectacular time to come as plants flower and migrant birds return.

The Black Sea coast is the destination of most summer visitors, with its inexpensive water sports, fine beaches and lively nightlife, though increasingly the mountain resorts are attracting people to their new golf courses, as well as to more traditional summer activities such as hiking, biking, climbing and horse riding.

The summer is a good time to visit if you enjoy folklore and traditional festivities, as many small towns and villages organise local celebration. It can be almost too hot for sightseeing in Sofia and Plovdiv in summer, so it’s best to time a cultural visit in spring or autumn.

The winter is beautiful in the mountains and Bulgaria has some fine ski resorts. Music lovers might like to visit some of the big cities in winter, as there is a full programme of operatic and classical performances, as well as excellent restaurants, bars and nightclubs.

The choice is yours.

What to see and do in Bulgaria

Belogradchik

The minor roads from Chiprovtsi to Belogradchik make a pleasant approach to this small Bulgarian town. There is a fascinating big yard used by charcoal burners, each dome of wood being a perfect hemisphere, despite being made from the heaps of stiff, awkward and angular branches. Closer to Belogradchik the landscape gradually changes and distinctive red rocks in crazy shapes dominate the view. The rock formations cover a huge area of over 50km2 and the town itself is situated among them.

For most visitors, the main attraction is this rocky landscape. Local people have given names to the most distinctive rocks: the bear, the mushrooms, Adam and Eve, the monk, the camel, the cuckoo, the horseman and many more.

Legends about the origins of the stones abound. In the past, one such story relates, there was a nunnery near the rocks. Sister Valentina, who took the veil and joined the nuns, was said to be very beautiful and rumours of her loveliness spread far and wide, even reaching a poor shepherd boy called Anton. Every night he tried to woo Valentina by playing his shepherd’s pipe beneath her window. Apparently the musical Romeo was successful and Valentina fell in love with him. Later she gave birth to a child and was of course expelled from the nunnery. God’s anger was turned on the convent and all the nuns were turned to stone; Valentina became a stone Madonna and poor shepherd Anton waits for his love among the stone figures.

In fact, the rock formations are a result of millions of years of geological activity as stratified rocks were covered by a sea in which river sand, gravel and clay were carried. In time these materials were joined together by silicon or sand-clay solder. Local iron oxide caused the redness. Other rocks of grey and white limestone were piled on top in some places during the Jurassic period, and because of the different levels of hardness the rocks have eroded unequally, thus creating the fantastic outlines of today. Amid this rockscape are caves and waterfalls, and the area is a haven for many unusual flowers and birds.

The natural rocky fortress on the edge of the town has three parts, each of which could be defended separately, and two main gates, named Vidin and Nish, presumably because of the direction they faced. There were barracks, arsenals, food stores, a prison, water cisterns and a flour mill. It housed about 3,000 defenders, and was last used during the Serbian–Bulgarian war of 1885.

The citadel, which is built into and amid the rocks, is the destination of most visitors. Its obvious strategic significance means that it has been a fortified site since Roman times, with Bulgarians and then Turks adding to its defences. Over time it has been the guardian of the approach to the Belogradchik Pass and a Turkish garrison intended to overawe the local population.

Koprivshtitsa

Koprivshtitsa is a place that deserves to be thoroughly explored – not just the house-museums, lovely as they are, but all the little alleyways.

There are stone water fountains (чешми) to discover, fascinating details such as door handles to notice, and a variety of unusual colours on the houses: deep blue, cinnamon brown, light blue, yellow and a wonderful dusty violet. There are monuments and statues, and in summer the hills all around are a sea of wild flowers and a source of wild strawberries, raspberries and other fruits.

Visitors should obtain a map from the tourist information centre or ticket offices on the main square for orientation.

What to see and do in Koprivshtitsa

The house museums

The town is the birthplace of several well-known Bulgarians. Some of the Koprivshtitsa House-Museums recount their lives and display artefacts connected with them. Each house has a special charm and, as they are scattered around the town, a visit to all of them gives you a good itinerary for a walk. A permanent exhibition by the Georgi Benkovski House-Museum, Koprivshtitsa – Educational Centre during the National Revival is included in the joint ticket.

The earliest houses, in a very simple style, were built of wood and only one storey. Most of these were destroyed in the 1793 attack by Kurdzhaliya. One example remains: the Pavlikenski House (not open to the public). Those built in the first half of the 19th century, of which the Benkovski House is a good example, were two-storeyed with a veranda and sturdy doors. In the second half of the century the houses were larger and much more lavish. They had many windows, elaborate carvings and decorated ornamental niches (alafrangas), following the Plovdiv tradition.

The most popular to visit are Oslekov House and Todor Kableshekov, while Lyutov House, on the other side of the river, is considered the pinnacle of Koprivshtitsa’s building achievements.

The churches

The town also has two churches. The Assumption of the Virgin Mary, built in 1817, replaced the one burned down by Kurdzhaliya at the end of the 18th century. The icons and woodcarvings are by well-known craftsmen including Zahari Zograf. The iconostasis and pulpit are particularly elaborate. The church itself is inconspicuous, as the Ottomans required, and painted bright blue like many of the nearby houses to avoid drawing attention to itself. The prominent bell tower was added much later.

The so-called new church, built in 1844 and dedicated to Sv Nikolai, was funded by wealthy families in the town. Sv Nikolai is the patron saint of those who travel by sea or make long and hazardous journeys, so he was an obvious choice for the well-travelled merchants of Koprivshtitsa.

Nesebur

The beauty of Nesebur is threatened by its proximity to Sunny Beach. In high season it is very busy, and stalls, cafés and restaurants vie for the visitor’s attention. Yet even then actually, if you walk away from the centre, it is still just possible to get a feel for this little peninsula as it once was. This small space was home to as many as 40 churches constructed between the 5th and 17th centuries, many of which remain in part or whole.

This Bulgarian settlement is one of the oldest in Europe, with traces of Thracian settlement in the 2nd millennium BC. During the time of ancient Greece it was known as Mesembria, and was part of the Roman Empire in the 4th to 6th centuries. It retained this name until about the 11th century. Then, as Nesebur, it changed hands many times between the Byzantine and Bulgarian empires in the 12th and 13th centuries, but in the 14th, when it remained Bulgarian, it flourished, and many of its most interesting sites are from this time.

What to see in Nesebur

After crossing the causeway with its wooden windmill, once a common sight on the coast, you see the town gate and the ruins of some outer walls, layers surviving from Greek, Roman and Byzantine eras.

The numerous churches dotted around the peninsula are the wealth of Nesebur, many in the traditional local style with bands of white stone alternating with red brick, often decorated with blind arcading, ceramic discs and rosettes.

Holy Pantocrator Church of Christ

Situated close to the town gate, this medieval church dates from the 14th century and is one of the best-preserved in Bulgaria. The shape is cruciform and domed, and the stone and brick exterior is decorated with ceramic inserts.

The frieze of swastikas always attracts the attention of visitors; the swastika is an old religious symbol based on the form of a Greek cross. There is usually an exhibition by local artists inside the church.

Sv Ivan Aliturgitos

Meaning St John the Unconsecrated, this architectural masterpiece is close to the harbour and entrance gate. This church is beautifully adorned and its striking silhouette is often used in photographs to demonstrate the skill of local church builders.

The details are fascinating: patterns of mussel shells, images of the sun, decorative plaques, crosses and even four-leafed clovers. This was built in the 14th century, but much damaged by the 1913 earthquake.

Plovdiv

With its attractive Old Town, Plovdiv is often considered more appealing than Sofia: much of its charm lies in the incongruous juxtaposition of ancient, medieval and modern. The development of the Kapana Creative District has revitalised the new town and attracted young artists to the city. Known as Phillipopolis in ancient times, and Filibeto by the Turks, Plovdiv has Classical remains, Byzantine churches, mosques and some of the country’s finest National Revival domestic buildings. It is also an excellent base for exploring the Rhodope Mountains and villages.

Approaching from the north it is easy to understand why Plovdiv is an ancient settlement, as its hills rising from the Thracian Plain are the most significant natural landmark. It sits on both banks of the Maritsa River and has been a commercial and transport centre over the centuries. The climate is particularly favourable, with an early spring, a hot summer and a mild winter. Its strategic importance made it the target for invaders, and each new occupier has left their mark.

The treaty of San Stefano in 1878 envisaged Plovdiv as the capital of the newly liberated Bulgaria, as it was centrally placed, and already a commercial centre. However, the revision of the treaty at the Congress of Berlin was dominated by the Western powers who feared the expansion of Russian interests in the Balkans.

They divided Bulgaria into two parts: the new principality of Bulgaria and the province of Eastern Rumelia which was to remain under the influence of Turkey, with Plovdiv as its capital. The two united in 1885 on 6 September, a date which is still celebrated as a national holiday. By then Sofia was established as the new capital, and Plovdiv remains a splendid second city.

What to see in Plovdiv

Plovdiv is divided into two main parts, the Old Town built on three hills and the modern central area, which includes the popular Kapana Creative District, a pedestrianised area full of shops, restaurants and galleries. Elsewhere in the new town are some other Roman and Ottoman sites of interest.

Ancient Theatre of Phillipopolis

The photogenically cobbled Old Town is a place to wander and savour. The labyrinthine street pattern means following your nose is a better strategy than following a map. All roads seem to lead to the Ancient Theatre of Phillipopolis. Plovdiv’s most famous and spectacular landmark seats 4,000 spectators in 11 semi-circular tiers set into the hillside.

The backdrop of the stage is a tastefully restored façade of Ionic columns and statues – and the navy outline of the Rhodope Mountains behind that. Visit is you can during an evening concert or performance for the full effect of the place.

National Revival-style houses

Plovdiv has some of the finest National Revival-style houses in Bulgaria. Entry to each house is 5lv. A route ticket (available from participating houses and Tourist Information Centres, 15lv; valid 48hrs) gives entry to five houses. There is also a Plovdiv City Card (22lv; valid 24hrs) which gives free entry to over ten venues (a few of the National Revival houses, but not all), as well as the Roman Theatre and some museums, and discounts at selected restaurants and shops.

The architectural challenges of building on steep, narrow streets have been met and to overcome the lack of space at street level, the upper storeys were built outwards on wooden beams and trusses so they almost meet across the street above your head. Many of these Old Town houses have been restored and are open to the public – for most visitors, two or three will be sufficient.

Ethnographic Museum

The Ethnographic Museum is in a beautiful old house, dating from 1847. Probably Plovdiv’s most photographed building, it was built for a rich Greek merchant, Argir Kuyumdzhioglou. Sometimes on a summer evening there are chamber music performances in the garden; a small fountain adds its music, and the slightly sour smell of box trees and the sweeter perfume of roses complete the sensory experience.

The museum opened in 1962, and has a rich collection illustrating local skills such as the making of tobacco, wine and cheese, textiles and weaving, costumes, folklore traditions and music. The house itself is a joy to be inside, especially is you are lucky enough to catch it at a quiet time. The ceiling in the main upstairs hall features a stunning rosette and sunburst pattern. Outside, the roof sweeps in voluptuous curves, and ornate felt wreaths decorate its façade.

The New Town

Two mosques of note sit in Plovdiv’s New Town. The Dzhumaya or Friday Mosque probably dates from the 14th century. It is a very large, fine building with beautiful floral motifs inside. It was and is the major mosque in Plovdiv. Its minaret is particularly eye-catching, with its diagonal pattern of red bricks on white mortar. Visitors who find the mosque open are welcome to enter. Northeast of the mosque was traditionally a bazaar area and it is still busy with shops, cafés and stalls, which continue across the footbridge over the River Maritsa.

The Imaret Mosque was built in 1444 and named after the imaret or pilgrims’ accommodation that was nearby. It stands in a small garden and has been restored in recent years. The twisted patterns on its minaret are striking.

Rila Monastery

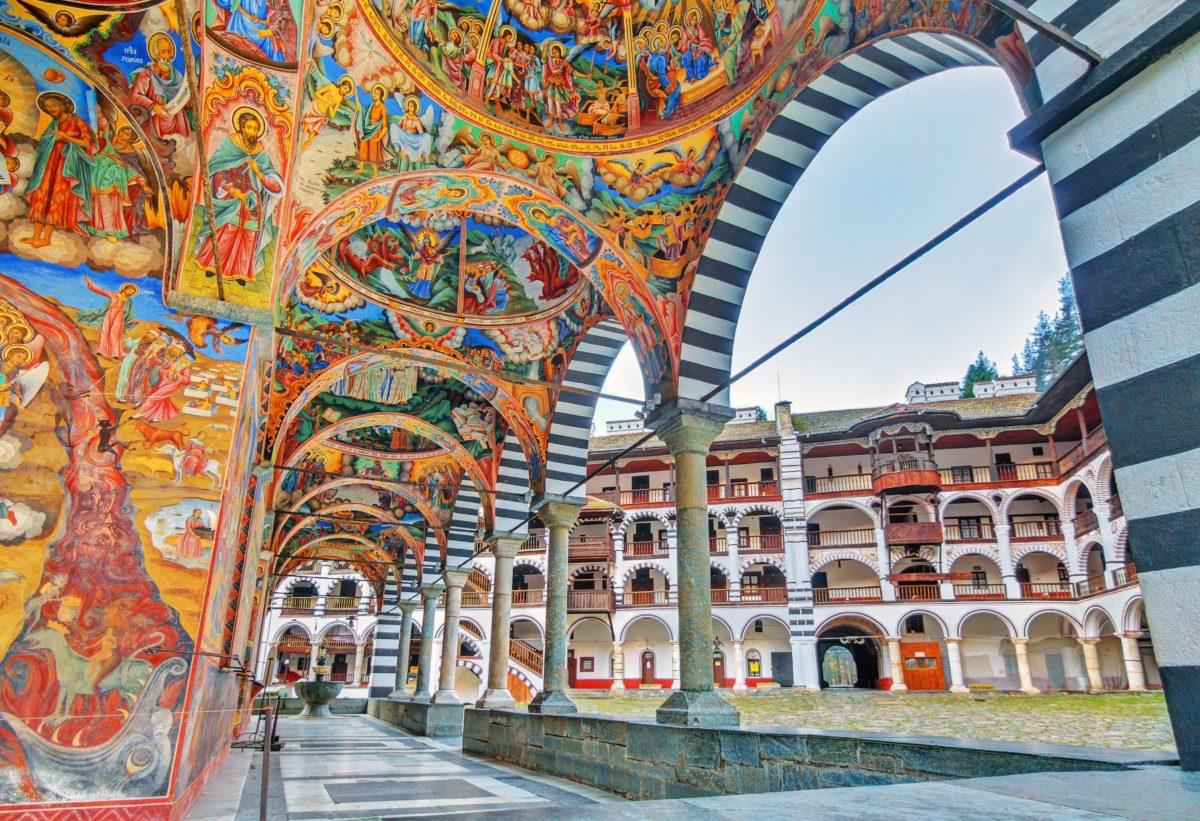

The road to Rila Monastery runs beside the River Rilska through beautiful wooded mountains. In summer and at weekends it is exceptionally busy, and, surrounded by buses and cars, it is hard to imagine what a remote and quiet place this was for most of its history. If you can arrive early, perhaps on a winter morning when a dusting of snow picks out the architectural features, then you may experience that feeling of awe at the immense walls and astonishment at the vibrant colours in the courtyard.

The first sight of the monastery’s towering exterior gives the impression of a fortress; in the past this security was necessary, as the wealth of the monastery attracted bandits and robbers, though its remote situation in the mountains and its altitude, 1,150m, helped to protect it. The founder, Ivan Rilski (880–946), was a hermit who sought enlightenment in the solitude of this place, but his reputation as a wise man with healing powers generated followers. In response to their requests he founded a religious community, which soon became a place of pilgrimage for people from all over the Balkans.

The monastery has occupied this location since 1335, a few kilometres southwest of the original hermitage, under the patronage of the bolyar, Stefan Hrelyo Dragovol. The oldest of the buildings visible today, Hrelyo’s Tower was built then.

The monastery suffered damage and destruction during the Ottoman conquest and the subsequent occupation, but after each setback renovation soon began again. The return of the relics of Ivan Rilski from Veliko Turnovo in 1469 was a significant event for the growing importance of the monastery.

After the great fire of 1833, the Ottoman sultan allowed the rebuilding of the monastery, and plentiful financial donations from the people, together with the gifts of time and skills by many great artists and craftsmen, resulted in the splendid building we see now.

Passing through the huge gates of the monastery for the first time is one of life’s special moments: the scene changes from grey severity to a carnival of colour. All round the enormous courtyard are tiers of monks’ cells behind boldly decorated, arcaded balconies. In the centre, the church itself, with richly coloured frescoes in the shelter of its porch, is the focus of attention, its lavishness emphasised by the simplicity of the 14th-century tower alongside it.

The temptation to conclude the visual feast by going straight into the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary should not be resisted. The iconostasis is a splendid mass of intricate carvings, heavily decorated with gold leaf. It is made of walnut wood and its subjects are from nature: flowers, fruits and birds.

The pulpit and bishop’s throne echo its magnificence and the colours are repeated and strengthened in the frescoes covering every available wall, ceiling and arch. Zahari Zograf, perhaps Bulgaria’s most famous mural painter, was one of the artists who worked here. The theme of the frescoes is the triumph of good over evil and light over darkness. The mood is optimistic and the colours light. The external frescoes have particularly lively depictions of the seven deadly sins and the descent of their perpetrators into Hell.

At the time of its completion it was the largest monastery church in the Balkans. It is a cruciform shape with several altars and two chapels. The acoustics are excellent, and hearing a service there is a wonderful experience. The service is preceded by a monk walking round the outside of the church banging a wooden stick, a ceremony said to be a reminder of Christ being nailed to the cross.

Sofia

Sofia has the buzz of a capital city and the convenience of a compact centre where all the main sights can be visited on foot, many on the famous yellow brick road, the central area paved in 1906–07 with stone ‘marl’ produced in a factory near Budapest. The city has a good selection of museums, religious buildings of several faiths and in many styles, from the ancient and unassuming Sv Sophia to the iconic Sv Aleksandur Nevski, and numerous good hotels, restaurants, cafés and bars. It has a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Boyana Church, and its own mountain, Vitosha, right on the edge of the city, providing skiing in winter and wonderful walks, climbs, flowers, birds and fresh, cool air in summer.

Sofia has only been Bulgaria’s capital since 1879 so its main boulevards are from the late 19th century, but in among them are some older sites: the Neolithic settlement at Slatina; the Roman rotunda of Sv Georgi and several recently excavated Roman buildings discovered during the construction of the metro; and the sunken Church of Sv Petka Samardzhiiska, which was built in Ottoman times.

There are several monuments and buildings reflecting Bulgaria’s long and close relationship with Russia: the sine statue of Tsar Alexander II the Liberator, the Russian Church of Sv Nikolai and the Sv Aleksnadur Nevski Memorial Chuch, for example. There is a mosque and a synagogue; indeed in the central pl Sv Nedelya you can see the Orthodox Church, the Banya Bashi Mosque, the recently built Catholic Cathedral of St Joseph and the Synagogue within a few hundred metres of each other.

Sofia in the 21st century has a real energy and a feeling of being a city that is on the up. It is also a rather placed city, expecially in summer, when people-watching while strolling and sitting at pavement cafés are favourite evening occupations. However, there’s plenty of culture available too: affordable opera, classical music, film and theatre. Bars, clubs and a wealth of excellent restaurants make spending a few, or indeed many, days in Sofia a pleasure.

What to see in Sofia

Sv Aleksandur Nevski Memorial Church

If you’re planning a walking tour of the city, it’s probably best to start here as it is the largest and most visible building in Sofia. Although the Church of Sv Sophia gave the capital its name, this much-photographed memorial church is the symbol of the city.

Sofia’s skyline is dominated by its gleaming golden domes. It was built in honour of the 200,000 Russian casualties who died fighting for Bulgaria’s independence in the Russo- Turkish War of 1877–78 and is named after Sv Aleksandur Nevski, a Russian prince who saved his country from invasion in the 13th century, and was the patron saint of Tsar Aleksandur II, Bulgaria’s liberator.

The foundation stone was laid in 1882, but the real construction works started in 1904 and finished in 1912 when a period of wars started in Bulgaria, so the official consecration only took place in 1924. Craftsmen and artists worked for many years to create this enormous church, which is said to hold over 5,000 people.

The belfry is 52m high and contains 12 bells, whose clamour is audible across the city. Its lavish exterior is, even so, surpassed by the frescoed interior and splendid iconostasis and the golden mosaics. There are nearly 300 mural paintings, including a dramatic vision of God in the main cupola and a Day of Judgement as a timely reminder above the exit.

Ivan Vazov National Theatre

The theatre was built in 1907 by two Austrian architects and is one of Sofia’s most elaborate buildings. Above the six white marble columns in the pediment is a scene of Apollo and the Muses, and on the two towers behind that the muse of tragedy Melpomene and the muse of dance Terpsichore are on chariots, drawn by lions.

The theatre has a capacity of 850 people. Inside there are colourful hangings woven by women from Panagyurishte and a vivid fire-bird on the stage curtain taken from Stravinsky’s ballet. In summer, lovely outdoor cafés are created in this area.

Mineral Baths

Bulgarians are generally rather interested in the different types of mineral water; sometimes in the most remote of places you will see a line of parked cars and a queue of people waiting beside a water spout with their plastic containers. The mineral baths in Sofia are no exception, and there are often long queues of people waiting to collect water from the tapped springs. This spectacular building was for a long time in a state of extreme decrepitude but has now been painstakingly restored to its original condition.

The larger rooms have become the exhibition space of the Sofia History Museum, which has long had a collection but until now no home. The exhibits include materials from archaeological excavations, coins, jewellery, weapons, clothing and the belongings of some famous figures such as Stefan Stambolov and Tsar Ferdinand.

Veliko Turnovo

Veliko Turnovo was the capital of Bulgaria during its period of medieval greatness (12th–14th century – Second Bulgarian Kingdom). After 500 years of subjugation under the Ottoman Empire, Veliko Turnovo was, symbolically, chosen in 1879 as the location for the meeting of the Grand National Assembly, which drew up the constitution of the newly liberated state.

Veliko Turnovo is probably the most picturesque Bulgarian city, its houses seemingly stacked up on the high banks of the sinuous River Yantra. In medieval times it was seen as second only to Constantinople in splendour, and it became a flourishing city again during the 19th-century National Revival.

It is set on three hills round which the river curves and loops. Each house is perched vertiginously on a precipice, some houses actually needing to be entered through the house below them. Every building has successfully overcome major architectural problems.

It is possible to walk along an alley with buildings towering above you on one side and an aerial view of a church belfry on the other. There are tantalising glimpses across to the Tsarevets and Trapezitsa hills, and wonderful views across the river to the wooded hillsides which surround the city.

It is worth going down to the riverbank in the evening; here frogs croak out their courtship songs, and the houses and lights are reflected in the water. From a distance the whole improbable structure of the city looks as if it is bound together only by the fragile lacework of vines, roses and geraniums which seem to grow on, up and over the houses.

Related books

Related articles

From carpet-weaving to fire-dancing.

What not to miss on a visit to this culturally rich country.

Sit back and enjoy this kaleidoscope of colours.

While some are a carnival of colour, others are characterised by a serene tranquillity.

From stunning landscapes to sites of historical and cultural importance, monasteries provide a wealth of interest for the avid traveller.

There are many national parks in Europe that remain fairly unknown. Here you can discover 14 of the best. Why miss out on visiting somewhere spectacular?