Start with a straight road that runs for 320km. Put all the hills on one side and the flatlands on the other. Sprinkle the whole thing liberally with red bricks, (former) Communists and tortellini, and you couldn’t get anything else but Emilia-Romagna.

Dana Facaros and Michael Pauls, authors of Italy: Emilia-Romagna

Italy is so full of world-famous sights that most visitors, racing between Venice and Tuscany, only know Emilia-Romagna from the train window. The big chunk they’re missing, wedged between the Po River and the Apennines, is a fascinating, wealthy, multi-faceted region, where tourism, refreshingly, is only a side-line, but where a string of dazzling art cities and the country’s best food (yes, even the Italians agree), are reasons alone for a weekend break or extended holiday any time of the year.

Start with the regional capital, Bologna, home to the world’s oldest university, hypnotic porticoes, medieval churches, markets and century-old taverns, a city that outdoes Pisa with not one, but two tipsy leaning towers.

Three cities are World Heritage sites: Ravenna, filled with gorgeous, glowing mosaics, like love letters from the Dark Ages; Ferrara, the refined Renaissance city of the Este dukes; and Modena, home to an extraordinary Romanesque cathedral. Then there’s elegant Parma, the city of prosciutto and Parmesan cheese, ceramic-filled Faenza, and a dozen more.

But Emilia-Romagna isn’t just about cities, great art and eating fresh pasta. Discover the world’s top supercars or take in an opera or concert in the homeland of Verdi, Rossini, Respighi and Pavarotti. Stay in a frescoed Renaissance castle, or in an agriturismo outside a sleepy medieval hill town.

Relax in a thermal spa, walk or bike Apennine trails through national parks and ancient forests. Or hit the beach in Fellini’s beloved Rimini, queen of a string of Adriatic resorts, complete with theme parks for the whole family and Italy’s hottest nightclubs for dancing until dawn.

For more information, check out our guide to Emilia-Romagna:

Food and drink in Emilia-Romagna

Emilia-Romagna is Italy’s ‘Food Valley’, the queen of culinary delights, home of the nation’s favourite ham, cured meats, cheese and balsamic vinegar, not to mention a cornucopia of fruit and vegetables, seafood, wild mushrooms and truffles.

Every province, every village even, has its own specialities, which often appear on menus in Emilio-Romagnolo dialect to complete the bewilderment of the innocent diner. In general, dishes tend to be meaty but vegetarians need not despair; there will nearly always be options or that old standby, pizza. Vegans, however, may find it tough going.

Salumi

Salumi means cured pork products – cold cuts, if you will – and no place in Italy does them as well and as abundantly as Emilia-Romagna, where the most typical antipasto is a selection of salumi, called an affettati or tagliere (literally,‘cutting board’).

Piadine and other obsessions

What goes with your plate of salumi? A foaming glass of dry Lambrusco and a something else, depending where you are. In Romagna it’s sure to be a hot and savoury piadina, a soft round flatbread traditionally made with flour and lard. Each province on the Emilia side also has its own flatbread or focaccia or paste fritte or gnocco fritto – deep-fried little golden pillows.

Throughout Emilia you’ll find tigelle, made with yeast and lard baked in a round waffle-iron, and borlenghi, enormous crepes usually cooked out of doors and traditionally topped with cunza – a mix of chopped rosemary, garlic and lardo – folded and served, although some heretics replace the lardo with Parmesan.

In Reggio and elsewhere, look for erbazzone, a very thin rustic pie filled with spinach or chard, onions and sometimes pancetta or cheese.

Primi

Pasta is the classic primo, or first course. Many of Italy’s favourite forms originated here, and taste better here than anywhere else. Several come from the word torta, or twist, which describes how they’re made: the pasta is rolled and cut, the filling is spooned on, and sealed in a ring with a twist. The classic tortellini are part of the region’s mythology, and ideally served in capon broth.

In Bologna they are filled with pork, ham, mortadella and Parmesan. Bigger ones are tortelloni. Tortelli, usually stuffed with herbs and ricotta, or pumpkin or other fillings, can be twisted but are usually square or shaped like half-moons and served with melted butter and Parmesan, or a sauce. Another classic, tagliatelle should be ideally served with a ragù– the mother of ‘spag bol’, a dish as bastardised in the UK as mortadella has been baloneyed in America.

Secondi

Main courses (secondi) tend to be on the hearty side as well. One heraldic dish is stracotto, topside of beef, cooked for hours (or days, by some extremists) in wine with herbs and vegetables until it becomes incredibly tender; sometimes it has sausage and a garnish of mushrooms.

You may also find rosa di Parma: a fillet of beef tenderloin, stuffed with Parmesan and prosciutto, rolled up, roasted and sliced. Another classic, bollito misto, is several boiled meats served with sauces, which oft en comes on a cart (carrello dei bolliti), allowing diners to pick and choose. Coppa arrosto, a speciality of Piacenza, is pork cooked in butter, oil, garlic and rosemary, then doused with wine and roasted in the oven.

Rabbit is popular: coniglio alla cacciatora, sweet and sour, or coniglio saporito, rabbit stew with chicken livers, anchovies and capers, or even the elaborate coniglio in porchetta, a speciality around Cesena, made with deboned rabbit, flavoured with fennel, garlic and rosemary, bacon and rabbit liver then stuffed with minced beef and pork, rolled up and baked.

Cheese

Besides Parmesan and its Grana Padano cousins, Emilia’s cheeses include stracchino (delicious soft cow’s cheese, often eaten on an antipasti plate with salumi, in a piadina or even mixed in mashed potatoes) and fresh semi-soft ribiòla made in Piacenza.

In the Apennines, try soft white raviggiolo, one of the country’s oldest cheeses; unlike most, the curd isn’t cut, but is simply left to drain on fern or fig leaves. It’s usually eaten fresh with olive oil and pepper, or stuffed in pasta. In Romagna, look for formaggio di fossa, or ‘pit cheese’.

Sweet stuff

Unlike some regions in Italy, desserts are serious business in Emilia- Romagna, and often there are special dessert menus. Among the most traditional are sbrisolona, a crumbly, cookie-like cake, often flavoured with lemon zest or almonds; torta di riso, a delicate cake of rice, sugar, almonds and milk; zuppa inglese, the Italian version of trifle (the name seems to derive from the trifle that members of the Este family enjoyed while visiting the court at London); buslàn, hard ring-shaped biscuits flavoured with lemon zest, for dunking in dessert wine at the end of a meal; spongata, a dense cake filled with honey, nuts and candied fruit; and a dense chocolate-and-coffee cake from Modena.

For sheer decadence, it’s hard to beat a torta di Duchessa di Parma, a hazelnut cake laden with pastry cream, zabaglione, and chocolate ganache.

Wine and liqueurs

Stretching from north of Genoa to the Adriatic, Emilia- Romagna is Italy’s fourth biggest wine producer. Much of the wine ends up as cardboard boxes of supermarket plonk, but the region also produces some gems among its 77 DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata) wines.

Two of the region’s finest, Pignoletto from the Colli Bolognesi and Romagna Albana, get Italy’s strictest rating: DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita). Best known of the DOC wines are Lambrusco in Emilia and the rubyred, fuller-bodied Sangiovese (the ‘blood of Jove’) of Romagna, made from one of the main grapes of Tuscany’s Chianti, although the results are usually lighter and fresher; the finest bottles, however, can hold their own with the noble Tuscans. The third by volume is straw-coloured Trebbiano, a refreshing single-grape wine, best drunk young.

Beer

With its huge student population and thirsty summer tourists, beer has always been a serious tipple, though not a distinguished one. Now, however, Emilia-Romagna is playing a big role in Italy’s momentous beer revolution, with more than a hundred craft breweries (microbirrifici) and brew pubs, nearly all founded in the last decade or so. The best known, so far, is the Birrificio del Ducato, which since its foundation in 2007 has won awards and exports all over the world.

Health and Safety in Emilia-Romagna

Health

Aside from the risks posed by exposure to the sun (both in summer and winter), and the nuisance of mosquitoes, health issues in Emilia-Romagna are no different from those in other westernised countries. In most cases, free care in Italy from the national health system, the SSN (Servizio Sanitario Nazionale). For more information, call Emilia-Romagna’s health hotline (800 033 033).

There will be a hospital, clinic or local health unit (Azienda Sanitaria Locale, ASL) with a Pronto Soccorso (casualty/first aid department) in every town of any size. Pharmacy staff are trained to assist with most minor problems. If a pharmacy is closed when you need it, look for the card in the window with the schedule of the farmacia di turno (the closest one open) or call 1100 for the details of the three nearest pharmacies.

Most Italian doctors speak at least rudimentary English; otherwise the US Consulate in Florence (055 266 951), which serves Emilia-Romagna, has a list of English-speaking doctors and dentists.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on ISTM. For other journey preparation information, consult NaTHNac (UK) or CDC (US). Information about various medications may be found on NetDoctor. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

While Emilia-Romagna’s cities (especially Rimini and Bologna) get their share of petty crime – purse-snatchings, pickpocketing, minor thievery of the white-collar kind (always check your change), car break-ins and theft – violent crime is very rare. Nearly all mishaps can be avoided with adequate precautions. Scooter-borne purse-snatchers can be foiled if you stay on the inside of the pavement and keep a firm hold on your property (sling your bag-strap across your body, not dangling from one shoulder).

Remember that pickpockets strike in crowded buses or trams and gatherings; don’t carry too much cash, and split it so you won’t lose the lot at once. In cities and popular tourist sites, beware groups of scruffy-looking women with babies or children with pieces of cardboard, apparently begging. They use distraction techniques to perfection. The smallest and most innocent-looking child is generally the most skilful pickpocket. If you are targeted, grab hold of any vulnerable possessions or pockets and shout furiously; Italian passers-by or plain-clothes police will often come to your assistance if they realise what is happening. Be extra careful in train stations, don’t leave valuables in hotel rooms, and park your car in garages, guarded lots or on well-lit streets, with portable temptations well out of sight.

Female travellers

Women travelling alone or in small groups should not encounter any particular problems in Emilia-Romagna. If possible, try to avoid arriving or leaving big city stations late at night. There have been complaints in the past of harassment etc, though no more or less than in any other European city.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Emilia-Romagna is the most tolerant region in Italy, so much so that Pope John Paul II called it a ‘Sodom and Gomorrah’. Politically left-wing Bologna is the home to the national headquarters of Arcigay, Italy’s first and largest LGBTQ+ organisation. In country towns, a certain amount of discretion may be called for as you may encounter confusion and animosity, especially among teenagers and the elderly. However, hotel workers are unlikely to question a gay or lesbian couple requesting a double room.

Travelling with children

Italians adore children, and you shouldn’t encounter any problems travelling with yours. However, if you are travelling with minor children with different surnames, you may need proof of guardianship. Contact your Italian consulate before you leave.

Many hotels now offer family rooms; staying in an agriturismo on a farm can be a great experience for kids. Children usually get half-price admission in museums. Children aged 4–11 years inclusive pay the child fare on Trenitalia; on long-distance trains those under 15 qualify for the child fare. Children under four travel for free, although you’ll still have to pay a small fee for a reservation. On Italo trains, children under two travel for free, while those aged 2–16 are eligible for a child rate.

Information for travellers with a disability

Emilia-Romagna is one of the best-equipped Italian regions for visitors with disabilities, although wheelchair users may well have difficulties in steep Apennine villages. Most hotels have at least one room designed for wheelchair travellers; public toilets and most restaurant toilets are accessible. Trenitalia provides free assistance to wheelchair users if you let them know your plans 24 hours in advance. Big city stations have a Sala Blu for travellers with disabilities where journeys can be arranged.

Travel and visas in Emilia-Romagna

Visas

According to the Schengen Agreement, citizens of EU member states and holders of passports from some 50 nations do not need a visa for stays of 90 days or less. These include Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Israel, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, South Korea, Singapore, Switzerland, the USA and, very likely, the post-Brexit UK.

Theoretically, all foreigners are required to register their presence with the police within eight days of their arrival in the country, but in practice few people bother; in any case, your hotel will take your passport and residence details for this exact purpose. Be aware, however, that if you are a non-EU citizen and get in a jam with the police, they can take your failure to report your arrival as evidence that you have already overstayed the legal period.

EU citizens can stay beyond 90 days if they have employment, sufficient resources, or an approved course of study. Even so, it will require filling out a form at the local police station or anagrafe (registry office). Non-EU family members will need to apply for a residence permit, a permesso di soggiorno. After five years, EU citizens and family members have the right to a permanent residence card.

For citizens of non-EU countries, extending your stay in Italy beyond 90 days can be rather difficult; you’ll need to come with an entry visa, before applying for a permesso di soggiorno through the provincial Questura (state police office). An entry visa is based on study, work and elective residence, few of which are entirely clear in their regulations or what’s required in order to secure one. Whichever you need, expect the rules to be infernally complex, onerous and confusing. See the websites of the Polizia di Stato and the Foreign Ministry, although their information is often contradictory.

Getting there and away

By air

Bologna is the main gateway to the region, with flights from 92 destinations around Europe and North Africa (all listed on the airport’s website). There are no direct flights from North America (the nearest airports with direct connections are Milan and Venice) or from Australia or New Zealand, although the daily direct flights on Air Emirates via Dubai make it the most direct route to the region.

By rail

From the UK, take the Eurostar across the Channel and connect with a fast train; if you’re lucky, a journey from London St Pancras to Bologna can take as little as 12 hours, changing in Paris (Gare du Nord to Gare de Lyon) and Turin. Trenitalia (892021) operates much of Italy’s domestic rail network.

Note that all the high-speed Freccia (‘arrow’) trains (Frecciarossa, Frecciargento, etc) require a reservation, though these come with the ticket. Some city-centre agencies sell Trenitalia tickets, and you can also buy e-tickets online or from the machines at the stations. Trenitalia’s competition, Italo (892020), operates state-of-the-art high-speed trains, with stations in Bologna, Reggio Emilia and Ferrara; trains zip from Milan to Bologna in 53 minutes.

By coach

A number of coach companies operate services from various European countries to Emilia-Romagna. Check out Bus Web for information on services including times, prices and booking options.

By car

It’s 1,340km from Calais to Bologna by way of Grenoble, the Mont Blanc Tunnel and Milan, and costs €152 in tolls. It’s much cheaper (tolls €20), if slightly longer, to travel instead via the A61 and A2 (Brussels, Cologne, Basel, Lugano and Milan). Italy has an excellent network of toll motorways (autostrade). For a useful journey planner, visit the autostrade website.

Getting around

Emilia-Romagna has excellent public transport, and you really can see its great art cities and towns by riding its frequent and affordable trains or buses without the expensive headache of finding a place to park and/or dealing with the limited traffic regulations in most historic centres.

By rail

Trenitalia, still often called by its old name, the Ferrovie dello Stato (FS), operates much of the country’s rail network. Tickets can be purchased up to three months in advance – your best chance to bag a discount. Economy fares and family fares are available if you purchase the ticket at least two days in advance. If you change your mind about the date, you have up until 23.59 on the day before travel to change it one time only.

Italo is Trenitalia’s state-of-the-art high-speed competitor. At present, it serves Bologna, Reggio Emilia and Ferrara. There is a variety of tickets available at the stations or online: low-cost, purchased up to three days in advance; economy, which allows you to change times and dates up to 3 minutes before departure, and offers 60% refund if you cancel; and Flex, similar to economy with an 80% refund if you cancel.

By bus

Italian bus services are excellent: modern, clean, frequent, punctual and inexpensive, generally cheaper to travel on than trains. Four firms serve the region: SETA (840 000216) for the provinces of Piacenza, Reggio Emilia and Modena); Tep (0521 2141) for Parma; TPER (051 290290) for Bologna and Ferrara; and StartRomagna (199 115577) for Ravenna, Forlì–Cesena and Rimini.

A new service, Mi Muovo Multibus (800 388988) allows you to travel all through Emilia-Romagna with a single €15 bus pass on all the region’s bus lines; good for twelve 75-minute journeys, in any combination (three people, for instance, can make four journeys). Pick up tickets at any of the local offices. Also check schedules with Baltour (0861 199 1900), a low-cost bus line that serves parts of Emilia-Romagna.

By car

Driving can be fun and fast on the autostrade but slow and frustrating elsewhere. Every city and town centre is enclosed in a pedestrian zone, or ZTL (zona traffico limitata); trying to tour them with a car will only make you miserable. The only place where you’ll really wish you had one is in the Apennines, where connections between villages aren’t always convenient. Petrol stations are generally open 07.00–12.30 and 15.30–19.00 Monday to Saturday. There are 24-hour stations along the autostrade.

Car hire

Car-hire companies are the same you would expect to find anywhere else in Italy: Hertz, Avis, Europcar, Sixt and Maggiore. Most have branches in the major cities, at Bologna and Rimini airports and at the main train stations; most domestic one-way rentals carry no surcharge. You must be at least 18 (age may vary by car category) and have held your licence for at least a year. Some companies will only rent to drivers aged 21 and over; drivers under 25 may incur a surcharge. There is no maximum age.

When to visit Emilia-Romagna

When to visit

Emilia-Romagna is a year-round destination. In summer, millions come from around the world to bake on the beaches along the Adriatic Riviera. In August, hotel prices are at their highest on the coasts, but lowest in the cities as the locals abandon them for the beach (although many of the best restaurants close then).

As elsewhere in Italy, spring and autumn are the loveliest times for touring. The sights are rarely crowded and temperatures are mild. In many ways the cities are at their best in winter: opera season runs from December to March, hotels are cheaper (though beware of major trade fairs), you can have many sights to yourself and the rich, hearty food of the region tastes best.

Climate

The Po plain can be hot and muggy in summer, with daytime temperatures often above 30°C, but relieved by the occasional thunderstorm. Spring and autumn are mild, while winters are cool, wet and foggy.

It occasionally snows, while up in the mountains there is enough white stuff in winter to maintain some modest ski resorts. The coast is reliably sunny and hot from June until August, but can get surprisingly rainy in September and surprisingly chilly in winter; in Rimini the average January high is 7°C, and in Parma 4°C.

What to see and do in Emilia-Romagna

Bologna

‘You must write all the beautiful things of Italy,’ said the Venetian on the train, but the man from Bologna vehemently shook his finger. ‘No, no,’ he insisted. ‘You must write the truth!’

And it is precisely that, a fervent insistence on the plain truth as opposed to the typical Italian delight in appearance and bella figura, that sets Bologna apart. A homespun realism and attention to the detail of the visible, material world are the main characteristics of the Bolognese school of art (recall Petrarch’s comment that, while only an educated man is amazed by a Giotto, anyone can understand a Bolognese picture). The city’s handsome, harmonic and well-preserved centre disdains imported marble or ornate stucco, preferring honest red brick. Bologna’s municipal government, which was long in the hands of the Italian Communist Party (now the PDS), is considered the most efficient of any large city in Italy.

In the 11th century it was the desire for truth and law that led to the founding of the University of Bologna, whose first scholars interpreted the law codes of Justinian in settling disputes over investitures between pope and emperor. And it is Bolognese sincerity and honest ingredients in the kitchen that has made la cucina bolognese by common consent the best in all Italy, a fact recently confirmed by the opening of Fico Eataly World, the world’s first theme park dedicated to food.

The city’s historic centre is considered one of the best preserved and maintained in Italy, to the credit of its policy of ‘active preservation’, developed in the 1970s – old houses were gutted and renovated for municipal public housing, maintaining the character of the old quarters. Nor is this the first time Bologna has found a creative solution to its housing needs.

One of the first things you notice is how every street is lined with arcades, or portici. The originals date from the 12th century, when the comune, faced with a housing shortage compounded by the presence of 2,000 university students, allowed rooms to be built on to existing buildings over the streets.

Over time the Bolognesi became attached to them and the shelter they provided from the weather. Along with the absurdly tilting Two Towers, they are the city’s soul, its identity; to the Bolognesi, their special world is the pianeta porticata, the ‘porticoed planet’. The city claims 70km (including the single 4km portico that climbs up to San Luca), more than any other city in the world.

La Dotta, La Grassa and La Rossa (the Learned, the Fat and the Red) are Bologna’s sobriquets. It may be full of socialist virtue, but the city is also very wealthy and cosy, with a quality of life often compared to Sweden’s. The casual observer could well come away with the impression that the reddest things about Bologna are its bricks and its suburban street names such as Via Stalingrado, Via Yuri Gagarin and Viale Lenin.

But Bologna is hardly a stolid place – its bars, cafes and squares are brimming with youth and life, and there’s a full calendar of concerts from rap to jazz to Renaissance madrigals, as well as avant-garde ballet, theatre and art exhibitions.

Brisighella

Brisighella, 12km south of Faenza in the Lamone Valley, is a charming colour-drenched village, a certified ‘Slow City’ and thermal spa with an unforgettable skyline of sharp crags crowned by the golden towers of the castle and the Torre dell’Orologio, the latter originally a respectable guard tower (1290) with a clock slapped on the front.

Brisighella produced much of the clay fired in Faenza’s kilns – next to the village you can see the gashes left in the hills by the old quarries. So precious was this cargo that a protected, elevated passageway, the Via degli Asini (road of donkeys), was built through the centre that could be sealed up at either end in case of attack. Be sure to visit at the weekend, when the sights are open.

Olive oil and artichokes

Brisighella has been on foodie maps for decades, thanks to its unusual thick green olive oil, the first in Italy to be designated DOP (Denominazione di Origine Protetta).

It all has to do with what the French call terroir: it’s one of the coldest places in Italy where olives grow, but it means the olives ripen more slowly and aren’t plagued by the olive fruit-fly pest. The Apennines here are lower than the mountains to the west, allowing warm Tuscan breezes to dissipate the fogs and frost, while the unique chalky soil, poor in clay, maintains the summer heat.

The resulting oil is very low in acidity, but richer in fat, giving it an extra-long shelf life. Three varieties grow here in the 12km zone: Nostrana of Brisighella (the bulk); Ghiaccola (the fattiest, sold as Nobil Drupa) with a grassy, peppery taste; and even rarer Orfana (bottled as Orfanella), which is mild and lighter.

In springtime, don’t miss Brisighella’s other one-off: carciofo moretto, long, pointy, reddish-purple artichokes that grow nowhere else in the world. They are tender enough to eat raw, or boiled for a few minutes and served with olive oil and salt, or in salads, or in a hundred other local recipes.

Ferrara

There’s been a certain mystique attached to Ferrara ever since Jacob Burckhardt called it ‘the first modern city in Europe’ in his classic Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. Whether or not Burckhardt was exaggerating can be debated endlessly; it is certain that the famous ‘additions’ to the medieval city in the Renaissance were far too ambitious. Ferrara, even in the most brilliant days of the court of the Este family, never had more than 30,000 citizens – not enough to fill the long, straight, rational streets laid out within the 9km circuit of its walls.

But what was a failure in the Renaissance is a happy success today. If Italian art cities can be said to go in and out of fashion, Ferrara is definitely ‘in’, popularised by a well-received international campaign to save its uniquely well-preserved walls, and a rebirth of interest in the city’s great quattrocento painters.

Thanks to the rather tyrannical Este, the charming city enclosed by those walls was one of the brightest stars of the Renaissance, with its own school of art led by the great Cosme Tura, Ercole de’ Roberti, Lorenzo Costa and Francesco del Cossa. Poets patronised by the Este produced three of the Italian Renaissance’s greatest epic poems – Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato (1483), Ariosto’s better-known continuation of the same story, Orlando Furioso (1532), and Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (1581).

Ferrara’s career as a centre of culture – along with its economy and its civic pride –went down the drain when the popes took over in 1598. Even more than in Bologna, the nearly three centuries of papal rule meant poverty and obscurity for the city.

It’s been a long climb back, but today Ferrara is a contented and very prosperous city of some 135,000, with a big chemical industry leading a diversified economy. The entire city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and its university is rated as one of Italy’s best. But don’t ask about the microclimate; it’s steamy and swarming with mosquitoes in summer, weirdly frosty in winter. A lot of its important buildings are still closed, under repairs from the earthquake of 2012.

Otherwise things are grand. Ferrara’s good fortune is to be off the tourist track. The people who are always getting in your way in Venice and Florence have never heard of the place; seeing the sights is a stress-free delight. Do it by bike. Ferrara’s proudest distinction right now is that of all European cities, it takes third place in the ratio of bicycles to people; many of the hotels are happy to lend or rent you one.

Labirinto della Masone

Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges was always fascinated by labyrinths, and in 1977 his Italian publisher Franco Maria Ricci made him a promise: he would create the largest one in the world. Designed with Pier Carlo Bontempi and Davide Dutto at Masone, Ricci’s family estate, the 8ha square labyrinth opened to the public in 2015. Consisting of 3km of paths lined with 200,000 bamboo plants, it’s set within an eight-pointed star reminiscent of the planned Renaissance city of Palmanova in Friuli.

The handmade brick buildings in the centre of the maze (which you can reach without going through all the turns) were inspired by writings on Utopia over the centuries. They house a museum with Ricci’s rich, eclectic art collection (the Carracci, Luca Cambiaso’s Venus Blindfolding Cupid, Houdon, Thorwaldsen and Art Deco pieces to name just a few) and books, including a copy of everything Bodoni ever printed. There’s a bistro and cafe, run by the Spigaroli brothers of the Antica Corte Pallavicina, and if money is no object there are two palatial art-filled suites, available by request.

Langhirano

The foothills south of Parma are the source of much happiness – almost all of the famous Parma hams are produced here, as well Parmigiano cheese, DOC Colli di Parma wines, mushrooms (porcini in autumn, prugnolo in spring) from Borgo Val di Taro, and truffles from around Calestano.

The Taro Valley was always an important route through the northern Apennines. It branches at Fornovo; one road (the SS308) follows the river before crossing the mountains into Liguria, and another (the SS62, paralleled by the A15 motorway) takes a more tortuous path over to Tuscany. Such a strategic area naturally has sprouted plenty of castles.

The most photogenic of all the duchy’s castles, Castello di Torrechiara is a magnificent brick fantasy, almost unchanged since it was built by Pier Maria Rossi ‘Il Magnifico’ (1413–82), humanist, linguist, astronomer and military captain. Visible from miles around, it’s defended by a double set of walls and four mighty towers, each surrounded and linked by covered walkways.

The elegant courtyard has ornate terracotta tiles; the ground floor has excellent frescoes by Cesare Baglione, who also painted the delightful cycle of acrobats performing impossible feats with hoops on the backs of lions. The castle’s best frescoes, however, are by Bonifacio Bembo in the beautiful Golden Bedchamber, where Pier Maria brought his young lover Bianca Pellegrini, and where he died in her arms. Bembo covered the walls with gold leaf (now gone) and a fresco cycle dedicated to their love and the Rossi’s 40 other castles.

Modena

Modena puts on a class act – ‘Mink City’ they call it, the city with Italy’s highest per capita income, a city with ‘a psychological need for racing cars’ according to the late Enzo Ferrari, whose famous flame-red chariots compete with the shiny beasts churned out by cross-town rival Maserati.

Sleek and speedy, Modena also has a lyrical side of larger-than-life proportions: Luciano Pavarotti was born here, and its scenographic streets take on an air of mystery and romance when enveloped in the winter mists rising from the Po.

Though it grew up as a feisty free comune in the Middle Ages, when it built one of Italy’s finest cathedrals, Modena learned its graces and style in a more aristocratic age, under the House of Este.

The city’s formative years came between 1598 and 1859, when it stood among the capitals of Europe – if only as the capital of the Este’s little duchy. In that period Modena was transformed into a model Baroque city, and its elegant streets filled up with churches, palaces and porticoes in the new style.

All this Baroque fussiness, however, is only a stage for a people as devoutly socialist as Bologna’s. Italy’s richest city is also one of its most progressive; Modena has the largest car-free centre in Emilia-Romagna, making it a delight to walk around.

The serene old capital of the Este comes back to life, and the Baroque effect is made perfect by the cadets of the National Military Academy, who live in the old Ducal Palace and never go out without their hats and capes.

Museo Ferrari

There are two Ferrari museums. One is in Modena, the other by the factory in suburban Maranello. A dedicated shuttle connects the two, with a stop at the Modena train station.

Museo Enzo Ferrari

Enzo Ferrari (1898–1988) loved his native Modena enough to put the city’s yellow on his badge, behind the prancing pony, and Modena loves Ferrari right back. Opened in 2012, this museum pays homage to his life and times.

The house where Enzo was born, next to the workshop where his father worked on rail carriages, has been restored to house the Museo dei Motori, with various engines on display from a small two-cylinder model to F1, along with a collection of race cars and videos.

Next to it rises the curving glass facade of a slick, ultra-contemporary hall in the shape of a yellow Ferrari bonnet (big enough to get in the faces of workers in the nearby Maserati factory).

Films cover Enzo’s long, colourful life (he died at age 90, still working on the blueprints of his next car). There are changing exhibits, which not surprisingly focus on cars, set up on white plinths. There are even three different sized Ferrari-shaped kennels where you can leave your pooch for free while you visit the museum.

Museo Ferrari Maranello

The older of the two museums was set up at the factory and testing track in Maranello: there are historic cars, F1 trophies and exhibits and films on the marque’s history, which boasts no fewer than 5,000 race victories around the world since 1940.

There’s a ‘pit stop’ and tyre change to recreate just what goes on there during a race, and F1 simulators for young and old. Tours of the Ferrari factory and the Fiorano Test Track can be booked in advance via the website.

Enzo Ferrari, who had his start building tractors on his father’s farm outside Modena, moved out to this village during war production in 1943, and promptly got bombed flat by the Allies.

Since the rebuilding, Maranello has been Ferrari City, the place where people throughout the town hear the buzz of the cars on the testing track and, as the town’s tourist bumph puts it, ‘listen for a false sound in the engine, as if it were a wrong note at the opera’. In fact, one division in the factory is dedicated to perfecting the precise sound of the engine. Each model has its very own tune.

It’s a strange little world: high tech, but at the same time an anachronistic stronghold of Renaissance-style Italian luxury craftsmanship. The town of Maranello also has an Enzo Ferrari Park, and a statue of the founder, 6m tall, unveiled for the centenary of his birth in 1998.

Parma

One of Italy’s great art cities, and the second city in Emilia-Romagna after Bologna, Parma’s many admirers cite her splendid churches and elegant lanes, her artworks and antiquities, the lyrical strains of grand opera that waft from her Teatro Regio – a house that honed the talents of the young Arturo Toscanini – and the glories of its famous cheese and ham at table as reasons not only to visit, but to return again and again.

Even the air in Parma is lighter and less muggy in the summer than that in other cities near the Po. There are plenty of castles in the countryside, and opera lovers can trace the career of Giuseppe Verdi around his home town of Busseto.

The French daily Le Monde once rated Parma as the best Italian city to live in, for its prosperity and quality of life. It would, of course, since Parma is also the Italian city most influenced by French culture, thanks to a remarkable episode in the 18th century when the city filled up with Enlightenment French artists and philosophes, followed by a booster shot of Gallicism when it came under the rule of Napoleon’s forsaken Empress, Marie-Louise.

Quality of life Parma has in abundance. You’ll eat well here, even by Emilia-Romagna standards, in Italy’s first UNESCO Creative City of Gastronomy.

But there’s more to Parma than food. It’s the place to see the masterpieces of Benedetto Antelami (active 1177–1233), the great sculptor trained in Provence whose baptistry here introduced the Italians to the idea of a building as a unified work in its architecture and sculptural programme.

Parma’s distinctive school of art began relatively late, with the arrival of Antonio Allegri, called Correggio (1494–1534), whose highly personal and self-taught techniques of sfumato and sensuous subtlety deeply influenced his many followers, most notably Francesco Mazzola, better known as Parmigianino.

No town its size is more devoted to theatre and music, and none is more tolerant (or indifferent) to its perennially underachieving football team, a bottom-feeder that recently went bankrupt and has now fought its way back to Serie B. But just how French is Parma? You can mull that over while munching a crepe, still a popular item in many Parma restaurants and street stands.

Po Delta Park

The main attractions along the coast from Mesola to Ravenna are the Po Delta and the magnificent Romanesque Abbey of Pomposa, though there are plenty of Italian family lidos in the vicinity if you’re tempted to join the summer ice cream, pizza and parasol brigades.

Duke Alfonso II was the first, at least in modern times, to start draining the marshes south of the Po Delta. Much of the land was planted with rice; a large part of the rest now belongs to the Parco del Delta del Po, one of Italy’s most important wetlands and a birdwatcher’s paradise, especially in the spring and autumn migrations: prominent among the 200 species sighted here are flamingos, coots, grebes, herons, a vast assortment of ducks, black-winged stilts, and owls in the wooded sections, along with that most overdressed of sea birds, the cavaliere d’Italia.

The white Camargue horse has also been introduced. The 54,000ha Parco Regionale Delta del Po, Emilia-Romagna’s largest park, is scattered along the coast south of the Po to the salt pans of Cervia. Parasol pine woods dot the coast from Ravenna to Cervia; at Bosco della Mesola you can visit a patch of the forest that once covered the entire Po plain, and close to Ravenna, the Oasi di Punte Alberete is the last surviving example of the flooded forests that once covered the delta.

Ravenna

Tucked away among the art towns of Emilia-Romagna there is one famous city that has nothing to do with Renaissance popes and potentates, Guelphs or Ghibellines, sports cars or socialists. Little, in fact, has been heard from Ravenna in the last thousand years.

Before then, however, this little city’s career was simply astounding – heir to Rome itself, and for a time the leading city of Western Europe. For anyone interested in Italy’s shadowy progress through the Dark Ages, this is the place to visit.

There’s a certain magic in three-digit years. History guards their secrets closely, giving us only occasional glimpses of battling barbarians, careful monks ‘keeping alive the flame of knowledge’ and local Byzantine dukes and counts doing their best to hold things together.

In Italy, the Dark Ages were never quite so dark, never the vacuum most people think. This can be seen in Rome, but much more clearly here, in the only Italian city that not only survived but prospered through those troubled times.

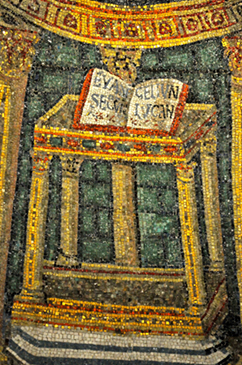

In Ravenna’s churches, adorned with the finest mosaics ever made, such an interruption as the Dark Ages seems to disappear, and you experience the development of Italian history and art from ancient to medieval times as a continuous and logical process.

Imagining Ravenna in its golden age takes some effort. It was Venice before Venice was invented, an urban island in a lagoon with canals for streets. Imperial processions through them must have been stunning. Unlike Venice, it was connected to the mainland by causeways. It contained a mixed population of Italians and Greeks, and its greatest ruler was an illiterate German warrior – the history is somewhat complex.

The advancing delta of the many small rivers that pour down from the Apennines gradually dried out all Ravenna’s magic, at least on the outside, but step inside the city’s ancient monuments, including eight sites on UNESCO’s World Heritage list, and you’ll see things you can’t see anywhere else in the world.

Rimini

Seen by the aliens from their spaceships, the Adriatic Riviera must be one of the most unusual and enticing sights of Europe. Welcome to ‘Linear City’ – 70km long and a few blocks deep, a mass of compacted (and mostly quite attractive) urbanity, with the SS16 and the Ravenna–Pesaro rail line on one side and a solid line of beach on the other.

It’s the place where Italians come because their grandparents did, where Germans come to look for Italians, the British come to fill shopping trolleys with gin, and Russians finally get a chance to wear their designer sunglasses. On any given night in August, more than 100,000 of them will be sitting down to tagliatelle al ragù in their hotels and thinking that life is pretty damn sweet.

There’s no place like it. And right in the middle is the surprising city of Rimini, home of one of the most beguiling monuments of the Renaissance and a vortex for weirdness of all kinds, from genuine haunted castles to hallucinogenically kitschy roadside attractions and the sovereign, independent Republic of San Marino.

At first glance Italy’s biggest resort may strike you as strictly cold potatoes, a full 15km of peeling skin and gelato, 10,000 selfie-taking teenagers with eternally whining, giggling little brothers and sisters. To many Italians, however, Rimini means pure sweaty-palmed excitement.

In the 1960s, following the grand old Italian pastime of caccia alle svedesi, a staple of the national film industry was the Rimini holiday seduction movie, in which a bumbling protagonist with glasses was swept off his feet by some incredible Nordic goddess, who was as bouncy as she was adventurous.

After many complications, embarrassing both for the audience and the actors, it could all lead to true love. For the bumbling protagonists of real life, all this may only be wishful thinking but they still come in their millions each year to ‘the Beach of Europe’. As a resort Rimini has its advantages. Noisy as it is, it’s a respectable, family place, relatively cheap, convenient and well organised, with the best nightlife in the north, if not all Italy.

Also, tucked away behind the beachfront is a genuine old city, with a four-star Renaissance attraction.

The Trebbia

‘Today I have gone through the most beautiful valley in the world,’ wrote war correspondent Ernest Hemingway in 1915, after driving through the Trebbia Valley, where the wild meandering river has carved verdant hills into odd-shaped cliffs and bowls.

The Trebbia’s sparkling turquoise waters are among the cleanest in Italy, perfect for a swim. Castles, one of Italy’s most offbeat museums and lovely places to stay dot the valley all the way up to Bobbio.

Museo della Merda

Founded in 2015, the ‘Shit Museum’ is the brainchild of Gianantonio Locatelli, owner of a dairy farm producing Grano Padano cheese – and 100,000kg of manure every day.

The tour takes in the farm’s ecological biomechanical works and the nearby methane-heated castle, featuring poop-inspired exhibitions including bioluminescent installations, dung beetles (the symbol of the museum) and art and household items made from ‘Merdacotta’, Castelbosco’s answer to terracotta, which are also on sale in the museum’s Shit Shop.

Castello di Rivalta

In a bucolic grove overlooking the Trebbia, this castle built by the Landi goes back to the 11th century, although the whole presents a stately Renaissance aspect; its round tower was built by an architect named Solari, who also designed parts of the Kremlin.

Inside are period furnishings, frescoes of country life, and a room of armour with three battle flags that were carried by the Christians at Lepanto in 1571. When the castle is very busy, there’s a mischievous ghost of a cook named Giuseppe who likes to turn lights off and on, close doors and move the furniture around; Princess Margaret, who spent ten summers here, met him at least once.

Rocca and Castello di Agazzano

This stronghold was begun in 1200, and mostly dates from the late 15th century. A cushier, U-shaped palace was added on the side in the 1700s, and a large French garden was planted between the two abodes. There are period furnishings and frescoed rooms to see; the cellar is full of the family’s Le Torricelle wine. The grounds of Agazzano’s other castle, La Bastardina, have been converted into a golf course.

Rocca d’Olgisio

Extending over a steep ridge east of Agazzano, this picturesque fortress enclosed in six walls goes back to at least 1037. Gian Galeazzo Visconti gave it to the condottiere Jacopo Del Verme, and it stayed in the family until the mid 19th century, after which all its furnishings were lost. The tour takes in a 16th-century loggia, walls and gardens; trails, some challenging, go to the odd-shaped grottoes underneath.

Villaggio Neolitico di Travo

This Neolithic village was excavated in the 1990s. Several huts have been reconstructed, and a museum with finds is a 10-minute walk away in Piazza Trento.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Emilia-Romagna:

Related articles

A trip to the capital of Emilia-Romagna offers some of the country’s greatest delicacies.

Discover some of the country’s finest architecture along this Roman road.

Even within a country that is itself known worldwide for its popular cuisine, the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy is famed for its delectable food.

It’s a world in itself, this pianeta porticata – ‘arcaded planet’, as the Bolognesi call their peculiar city. They like to be different, the Bolognesi.