My first visit to Estonia in 1992 was an adventure, travelling with a suitcase of soon-to-be-useless Russian roubles and wondering where I might next get petrol for the car.

Neil Taylor, author of Estonia: The Bradt Guide

The country had just gained independence from the Soviet Union, but I must admit it would have been hard to justify a Bradt guide in those days: Estonian towns were grey and I was often relieved to see green weeds as the only contrast in decaying concrete slabs. Since then, painters, designers, restorers and landscape artists have all had their part to play in ensuring that a walk in any Estonian town is now a pleasure, in the town centre or in the suburbs, in a park or by the sea.

By 1999, Estonia was certainly ready for a Bradt guide – it deserved more than just a few pages in a general Baltics guide. In the first edition, 200 pages was then more than sufficient to cover what a visitor might want to see, but this time around I am struggling not to go too far over 300, despite being as much a pruner as a writer.

While the country’s Soviet past is still evident in buildings and museums, it has no bearing anymore on day-to-day life in Estonia. More than half the population now has no memories of the Soviet occupation and they live in a world that could not be more different, one where the country looks to the West much more than to the East.

Over the coming years, the building of Rail Baltica from Finland to Poland will continue apace, linking Estonia firmly to the rest of Europe. NATO troops from a variety of countries are likely to be staying at the Tapa military base; they do not expect to participate in any action, but they symbolise, in a way that any number of words could not, how firm and loyal a member Estonia feels it is.

Tallinn receives constant accolades in the travel pages and on social media, all well deserved, but Estonia is so much more than the capital. Hopefully visitors will be enticed to the island of Hiiumaa, while its larger neighbour Saaremaa offers the best-preserved castle in the Baltics and the best-preserved windmills as well. Estonia’s second city, Tartu, will be the European Capital of Culture in 2024. Narva, on the border with Russia, hoped for this honour and will doubtless win it in due course, such has been its extensive transformation over the last decade. Buses, now travelling along well-surfaced roads, can whisk visitors to a host of isolated museums where individuals have dedicated their lives to collecting radio sets, weighing machines, bicycles and glass to name just a few passions. Churches have galvanised their parishioners into supporting extensive restoration, however small the local community.

Visitors will hopefully not only enjoy a holiday in Estonia but will feel an uplift from all that has happened in the country since 1991, in culture just as much as in business. On their return home, they will perhaps remember the Estonian contribution to any technology that they use, will enjoy being surrounded by Estonian crafts and perhaps will play some Estonian music whilst sipping a glass of Saaremaa gin.

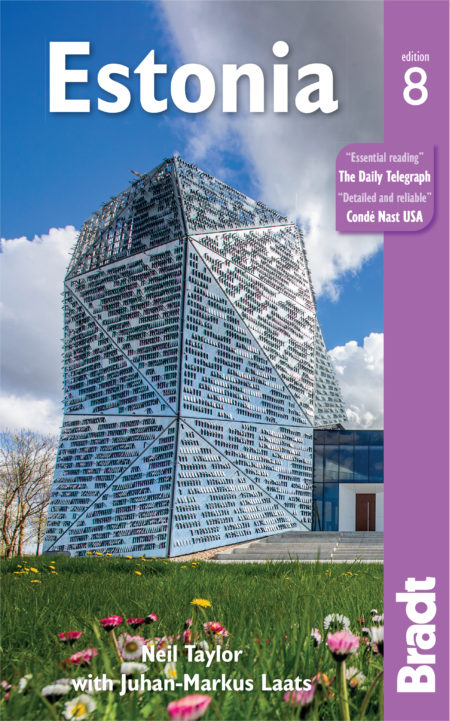

For more information, check out our guide to Estonia:

Health and safety in Estonia

Health

With regards to the Covid-19 pandemic, check the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office travel advice, including the country-specific pages, to get the latest information on travel restrictions, testing and quarantine requirements. Do this on a regular basis as changes can occur where there are rapid increases in case numbers.

No inoculations are required for Estonia as health standards are very high throughout the country. Still, travellers here as anywhere should be up to date with tetanus, diphtheria and polio, which now come as an all-in-one vaccine (Revaxis) that lasts for ten years. Hepatitis A vaccine may be recommended for longer-stay travellers or those visiting more remote parts of the country. Depending on what you are doing you may also be advised to be protected against hepatitis B and rabies.

Travellers planning to visit more rural parts of Estonia from late spring to autumn should take ample supplies of insect repellent, and are advised to take precautions against tick-borne encephalitis. Around 200 cases are reported each year. The worst-affected areas are Pärnumaa and Läãnemaa (west), Ida-Virumaa (east), Saaremaa Island (west) and Põlvamaa and Tartumaa (southeast). As the name suggests, this disease is spread by the bites of ticks that live in long grass and the branches of overhanging trees. Wearing hats, tucking long trousers into boots, and applying tick repellents can all help. It is important to check for ticks each time you have been for a long walk. This is more easily done by someone else.

If you find a tick then slowly remove it by using special tweezers, taking care not to squeeze the mouthparts. There is an effective vaccine available in the UK for adults aged 16 and over (Ticovac) and for children from one to 15 years of age (Ticovac junior). Two doses of vaccine should ideally be given about a month apart but can be given two weeks apart if time is short. A third dose should be given five to 12 months later if the traveller is at continued risk. Taking the preventive measures described above is also very important. Go as soon as possible to a doctor if you have been bitten by a tick (especially if you have not been vaccinated) as tick immunoglobulin may be needed for treatment. This is usually available in Estonia.

Tap water is safe to drink throughout Estonia; however, you may still prefer to drink bottled water, as the mineral content can be an irritant until you get used to it. Local hospitals offer a high standard of treatment for any emergencies. Most Western brands of medicine are available throughout the country.

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available here. For other journey preparation information, consult Travel Health Pro or CDC: Traveller’s Health.

Safety

Walking plays a major part of any tour in Estonia. Both in the towns and in the countryside many sites can only be reached and appreciated in this way. Whilst roads are usually well maintained, pavements rarely are, so be constantly on the lookout for pot-holes, ill-fitting manhole covers and loose paving slabs or cobbles. In winter, falling or dripping icicles are a further hazard but the accompanying sunshine that usually gives rise to this provides ample compensation. Town streets are well lit at night, important in midwinter when there are only 6–7 hours of daylight. Crime is less of a problem than in many other European countries and is very rare outside Tallinn.

Passports and unneeded valuables should be left in hotels; take the obvious precautions of dressing modestly and not flaunting money. Car theft is a problem at night so always use the guarded car park that most hotels have.

Female travellers

Estonian women might still have to do the majority of domestic chores at home, but at work and on the street they are equal. They can go to bars together, dress as they want and, with the high rate of divorce now prevalent, many live on their own, or often as a single parent. Women are in no more or less danger than men; pickpockets in tourist areas are opportunists on the lookout for anybody of either sex who they can take advantage of. Whether you are male or female, you are equally as vulnerable if you leave a bar after a few too many at 03.00.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Visitors to Estonia may be surprised at how limited the LGBTQ+ scene is. While the legal restraints faced by the gay community in Soviet times have all been abolished, the hostility has not been totally eradicated. In the communities living largely to the east of Tallinn, this may result from the continuing homophobic broadcasts picked up from over the Russian border. As a result, open affection outside the few gay clubs in the major cities is very unusual and visitors are advised to avoid this. And while civil partnerships are legal, same-sex marriage and adoption is not.

Travelling with children

Estonia is much more child friendly since joining the EU. Facilities on buses and at building entrances have been installed for people with disabilities and these are equally helpful for pushchairs. Tallinn Old Town, with its narrow, steep and cobbled streets, will remain difficult for small children, but elsewhere the flat landscape, the space and the mild summer climate make Estonia an easy destination for travel with children. Recently renovated museums all have children’s areas with games available linked to the exhibits. More playgrounds are being built, such as the one that opened in autumn 2020 in Tammsaare Park, beside Tallinn Opera House.

Travel and visas in Estonia

Visas

In 2007, Estonia and its Baltic neighbours joined the Schengen group of EU countries so there are now no border controls between them and no visas are needed for travellers from the UK, EU countries, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the USA.

For those who do need a Schengen visa, it is now valid in the three Baltic countries. The website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs lists Estonian embassies around the world that can issue visas to people entering the Schengen area through Estonia. It also lists foreign embassies based in Tallinn.

Getting there and away

From 1965 until 1988, Estonia’s sole link with the West was a twice-weekly ferry to Helsinki, yet it had daily flights to most of the then capitals of other Soviet republics. Now the situation is completely reversed, with minimal links east and an ever-increasing range of links to the West. Ferries go hourly to Helsinki and there are direct flights from Tallinn to most European countries. Bus routes link Estonia with Russia and with Latvia and some buses continue through Lithuania and Poland to western Europe. Trains operate daily from Tallinn to St Petersburg and to Moscow.

By air

Direct flights to Tallinn are operated by Air Baltic, easyJet and Ryanair from London’s Gatwick and Stansted airports. There are sometimes direct flights from Manchester and Edinburgh. Air Baltic also offer connections via Riga from London Gatwick and many European cities.

Helsinki is often used as a gateway for travel to Estonia; Finnair have multiple flights a day to Tallinn so there will always be connections with their onward flights to Europe, America and Asia. SAS offers a similarly wide range of connections via Stockholm and Copenhagen, while Turkish Airlines has a daily flight to Istanbul with extensive onward connections to all major airports in Asia. Finnair had a daily flight to Tartu from Helsinki until early 2020, but it is likely to be restored during 2022.

By ferry

The Port of Tallinn website gives full details of all services from/to Helsinki and from/to Stockholm.

By train

Rail services within Estonia and to/from the neighbouring countries consistently declined from independence until 2005 and were of little use either to business travellers or to tourists. However, there was then a sudden turnaround, with improvements every year in the quality of the rolling-stock, in frequencies and in speeds. The Tallinn–Narva and the Tallinn–Tartu routes are those of most interest to visitors. Tickets booked online in advance save about 15% on the prices charged on the train. There is a further reduction of around 20% for travellers aged 65 and above.

There is a daily service from Tallinn to Moscow, via St Petersburg, which takes 18 hours, and which is operated by Gorail, the company that runs the Schnelli Hotel next to the station in Tallinn. Tickets for this train can and should be prebooked abroad since the Russian visa will specify dates of entry and exit.

By bus

This is the easiest and cheapest way to reach Estonia from Russia and Latvia. Public buses always have priority over other traffic at the Russian border so delays there are minimal, but they are long enough to provide a respite for smokers.

International buses are operated by Eco Lines and by Lux Express. Wi-Fi is available on all buses and they all take about 4 ½ hours between Tallinn and Riga, with a short stop en route at Pärnu, where is also possible to join the service. About ten buses a day operate between Tallinn and Riga, usually with two classes on board, standard and luxury. Tickets can be bought at the bus stations, but given wildly variable prices, it is best to do some research before travel on the websites quoted above. Buses also operate from Tartu to St Petersburg and to Riga.

By car

Car drivers in the 1990s often had to face delays of several hours crossing each of the borders (eg: Poland, Lithuania, Latvia) between Germany and Estonia. Now that all the relevant countries are in Schengen, the borders are completely open. However, police do stop cars from time to time to check that drivers have all the correct documentation. The car ferries from Helsinki and Stockholm are convenient but expensive.

Car-hire rates are competitive in Estonia but in the short summer season it is normally essential to prebook. Travellers to Saaremaa or Hiiumaa can make considerable savings by asking their travel agents to arrange car hire separately on the islands and travelling by bus to and from Tallinn. This also avoids the difficulty of prebooking the car ferries from the mainland. Drop-off charges are high for cars picked up in one Baltic country and left in another so it is more economical to hire a new car in each country and to travel by bus in between.

When to visit Estonia

Estonia is warmer than many of its neighbours, thanks to the influence of the Gulf Stream. Harsh days do come each winter when temperatures can fall to –12 ̊C (10 ̊F), but such bitter weather rarely lasts for more than a few days. January 2012 was an exception, when temperatures dropped throughout the country for several days down to –30 ̊C (–20 ̊F).

In the summer, occasional heatwaves have brought temperatures of 30 ̊C (90 ̊F), but around 20 ̊C (65–75 ̊F) is much more common. There is no identifiable rainy season.

In December and January, with 18 hours of darkness, the days are so short that sightseeing outdoors offers little pleasure. October and March are excellent months with 12 hours of daylight, lower hotel prices and few other visitors. October offers autumn colours throughout the country and March the chance to enjoy snow-covered forests, the frozen sea and more sunshine than in any other winter month. The frozen sea often makes access to the smaller islands easier in winter than in summer since roadways are marked on the ice. Estonia follows the Scandinavian tradition of dealing with snow on the main roads immediately, so driving is rarely a problem in winter. All major roads are quickly cleared, even on Saaremaa and Hiiumaa islands.

In May and September there is little risk of cold weather and all outdoor facilities are open. By midsummer at the end of June, daylight lasts 18 hours, so July, the school holiday period in Sweden and Finland, is a very popular month for tourists. Fortunately for British visitors, August is no longer peak season so is ideal for those tied to school holidays. Throughout the year, rain tends to come in unexpected short sharp outbursts; always take an umbrella or a coat!

What to see and do in Estonia

Haapsalu

Its role as an air-force base restricted access until the end of the Gorbachev era and, as late as 1995, visitors were entitled to feel that it was a town looking backwards, not forwards. It had indeed much to look backwards at, with a turbulent history stretching back to its foundation in 1279, the year in which the construction of the castle was completed. Recent archaeological work has unearthed evidence of stone being used a century earlier.

Given its strategic location, every invader over the centuries had to secure the town, no matter at what cost. Most were to rebuild it, but Peter the Great, when he arrived in 1715, decided simply to destroy it so that the Swedes, with whom he was still fighting, would have little incentive to return. It would never again be seen as a major fortress. By 1715, as a result of war and plague, Haapsalu’s population had dropped to around 100 and even a century later it had only risen to 600. Its sudden rise to fame can be ascribed to one man, Dr Carl Abraham Hunnius, and to one product, mud. In 1825 Hunnius opened his first sanatorium and the popularity of the town was quickly established amongst the St Petersburg nobility.

Once the royal family showed an interest, as it soon did, the town’s continuing status was assured. Tsar Nicholas I himself came in 1852 for the first time, and Alexander II, who succeeded him in 1855, made repeated visits throughout his reign and Haapsalu became a major summer resort with a regular ‘season’. Tchaikovsky paid his first visit in 1867 and a wide range of his music was written in Haapsalu, including his Songs without Words and of course the Souvenir de Hapsal written in 1867. Soviet histories find it very difficult to cover this era in the town’s history, when support from the Imperial family, effectively Baltic-German entrepreneurs, and a rising Estonian middle class turned what had been barely more than a village at the beginning of the century into a resort on a par with many others in Europe by 1900. One history of the town, published in 1976, is forced to admit that ‘due to the mentality of the inhabitants, the town played a minor role in the revolutionary struggle’. A revolution in Haapsalu would have been as unlikely as one in Baden-Baden, Bath or Biarritz.

The sea is very shallow in the bay, which makes it warmer than elsewhere in Estonia, giving rise to the name ‘Africa Beach’. The water temperature is often around 21 ̊C (70 ̊F) in the summer, much higher than anywhere else in the Baltic Sea. The protection of the bay makes the sea less prone to storms, so the town became one of the most popular resorts along the Baltic coast.

What to see and do in Haapsalu

Haapsalu Castle

The town centre has always played the combined role of fortress and cathedral. When first built with local limestone at the end of the 13th century, it had a far more isolated location than it does now as it was right beside the sea and could be more easily defended. The land around it has risen quite considerably in the intervening seven centuries.

It has probably had the most turbulent history of any castle in Estonia, with frequent fires adding to the many attempts to conquer it. A convenient legend of the ‘Lady in White’, whose ghost stalks the supposedly all-male redoubt each August, has given rise to an annual festival centred on the castle with son et lumière performances each evening. She was alleged to have had an affair with a priest, disguising herself successfully as a pageboy for two years before being discovered. When this finally happened, her punishment was to be impaled on the castle walls. During full moon in August, her ghost can be ‘seen’ through the central window of the cathedral.

The ruins themselves involve tough climbs, so are not for the frail, but a walk around the outside walls, 800m in length, is not difficult. These ramparts date from the 16th to 17th century, when the Swedes built them, and consisted of seven towers and four gates. As so often with major fortifications in Estonia, they were never actually used, and were allowed to decay from the 18th century onwards.

Läänemaa Museum

This is housed in an 18th-century building, which was the Town Hall before World War II. In 1946 it was designated as a museum and through the Soviet era housed a collection of antiquities which had previously been in the castle. Since re-independence it has taken great trouble to bring to life Haapsalu’s history and every year it seems to expand its collection.

There are models of boats used in the harbour as well as Arabic coins to show the extent of early trade links. The archaeological collections have been put into one large case with a shelf for each century from the 13th onwards.

Getting to Haapsalu

Buses, both local and long distance, leave from the railway station forecourt and tickets can be bought in advance from the office inside the station (long-distance buses can also be prebooked on the website.

Ironically, since the closure of the passenger line in 1995, the only tickets the station can sell are those for buses (although at the time of writing in early 2021, the rebuilding of the railway line was being discussed). There are hourly services to Tallinn (1½–2hrs), as well as several services a day to Pärnu, Tartu and Hiiumaa Island. In summer, buses also operate to Virtsu for Saaremaa Island.

Kuressaare

The basic quadrangular structure took 40 years to build between 1340 and 1380 and the massive walls were added in the 15th century. The Germans, Danes, Swedes and Russians all maintained the original structure but the Russians withdrew their garrison in 1836 and from then the castle no longer had any military significance so escaped damage in later wars. It was therefore not attacked by the British during the Crimean War. Vestments and weaponry from each of these periods survives and is on display.

Not even bishops could live flamboyantly on Saaremaa in the Middle Ages. Austerity and simplicity are the impressions that remain. The original heating system still functions. Fortunately an early penal system does not – those sentenced to death in the second-floor Hall of Justice were allegedly thrown down a 20m shaft to be devoured by the animals waiting eagerly below.

There is an extensive exhibition of the history of Saaremaa up to 1940. The later period is of most interest to visitors; a wide range of memorabilia from the first independence period was hidden during the Soviet occupation but is now on view and is described in English. The presentation of a hardware shop shows the variety of goods available in the 1930s. This section could do with a redesign but at least the exhibition that opened in 2006 makes up for this. It covers the German and Soviet occupations, concentrating in particular on the World War II period. It is ‘hosted’ by a wax model of Konstantin Päts, Estonia’s pre-war president whose last major tour outside Tallinn was to Saaremaa on 20 and 21 August 1939.

Films and recordings bring that tour back to life and show the genuine enthusiasm with which he was welcomed. On 23 August, his subsequent fate was determined by Germany and the USSR in the Molotov–Ribbentrop agreement. A year later he would be in prison in Russia, as would be most of his cabinet colleagues, and many would soon be dead, although Päts himself was not in fact executed by the Soviet authorities and lived on in prison until 1956. For all Estonian visitors, the message is very clear. The 50 years between 1940 and 1990 were a mixture of horror and waste.

Among the exhibits from the communist era is a copy of the magazine Säde (Spark) from New Year 1977, which skilfully uses the three colours black, blue and white. That this was a reminder of pre-war independent Estonia was clear to most readers, but fortunately not to Russian censors. The stairs have jokes from the communist era written on each step in Estonian, English and Russian. One such is: ‘If capitalism is the exploitation of man by man, what is socialism? It is the exact opposite.’ An election rally is shown, hardly a necessary activity given that the Communist Party always claimed a 99% turnout in its favour. The forced smiles in some of these pictures can be contrasted with the genuine ones in the pictures mentioned above, taken when President Päts visited in 1939.

It is easy to miss the natural history gallery, housed in a basement close to the entrance. Apart from displaying every animal and plant that can be seen on Saaremaa, it has a special section devoted to juniper wood, on which the island’s economy will doubtless continue to be based. It is a very flexible material for furniture and the berries are a basis for gin.

During the summer, there is a full programme of concerts inside the castle; the surrounding park often hosts song festivals and carnivals. From the photographic point of view, the best shots of it are to be had from the port during early evening.

Lahemaa National Park

The von der Pahlen family, which owned Palmse Mansion, the architectural high point of a visit to the park, contributed to Estonia for two centuries with their administrative, commercial and academic activities.

Whilst to the west the Soviets would blight the outskirts of Tallinn with shoddy tower blocks and to the east ransack the coast with oil-shale exploitation, Lahemaa, the Land of Bays, was given the status of a protected national park in 1971 and great efforts were made to support and enhance the wildlife of the area. Similar support was given to restoration of the manor houses and fishing villages.

The boundaries of the park stretch for 40km along the coast and include several islands. Most Estonians, and all foreigners, were forbidden to enter the park because of its proximity to the coast but this did at least prevent any tourist and industrial development. Building work is now restricted to the minimum necessary to grant access to visitors and to provide for their stay.

What to see and do in Lahemaa National Park

Touring the park

Leave the St Petersburg highway from Tallinn to Narva at Viitna and then drive through Palmse, Sagadi, Vihula, Kunda, Altja, Võsu, Käsmu and Kolga before returning to the main road 18km further west. Drivers starting from the east or south will come off the main road at Rakvere or Viru-Nigula and begin the tour at Kunda.

Viitna is best known for its coaching inn, Viitna Kõrts, which dates from 1791. Like so many buildings in Estonia, it was destroyed at some stage in its history by fire; what is surprising is that the fire here was in 1989. Let us hope that it is the last serious fire to blight Estonian architecture. The inn appeals most in midwinter with its open fire and substantial portions of food, but at all times of year offers a good respite from the dull drive between Tallinn and the Russian border at Narva. It is no longer a hotel, but in the days of horse-drawn transport it served this function, being a day’s ride from Tallinn. The inn was clearly divided into two sections so that masters and servants would not eat together.

Palmse Manor

The manor is 6km off the main road, the perfect distance to ensure easy access but equally to ensure a totally calm natural environment. It is without doubt the most impressive manor house in Estonia and the 15 years of restoration between 1971 and 1986 have left a lasting and appropriate memorial to the von der Pahlen family. They were diverse in their brilliance, some entering Russian government service, some succeeding in business and some running this estate.

Among those still remembered are Peter Ludvig von der Pahlen (1745–1826) who, as Governor of St Petersburg, was one of the plotters involved in the assassination of Tsar Paul I in 1801, and Alexander von der Pahlen (1819–95) who initiated the building of the St Petersburg–Tallinn railway. The main building and the surrounding gardens were begun in 1697 but the Northern War between Sweden and Russia halted construction. It was completed in 1740 and then work started on the other buildings.

The family lived here until 1923, when the estate was nationalised in accordance with the Land Law of 1919. The land was then divided amongst ten families and the house became a convalescent home; after World War II the Soviet administration converted it into a pioneer camp for young people. The other buildings had all been left to decline and by 1972, when restoration began, were in such poor condition that it was necessary to consult drawings and photographs from the turn of the century to see their original format.

Sagadi

Sagadi is a 6km drive from Palmse and its manor house is very different. Local writers prefer it to Palmse, making comparisons with the chateaux on the Loire and even with the Garden of Eden. Travellers arriving with such expectations will definitely be disappointed, but those with a more open mind will see how a typical Baltic-German family lived and ruled. The land was owned by the von Fock family from the 17th century, but the current building, and those immediately surrounding it, date largely from the 1750s. Construction was not therefore hindered by the Northern War, which halted work at Palmse.

The façade was rebuilt in 1795, with the addition of the balcony. The von Focks had a variety of business careers, largely in shipbuilding and in forestry, but none reached the eminence of the von der Pahlens. The family lived in the building until 1939 although, following the Land Law of 1919, the estates were nationalised and the main building became a primary school. It kept this function until 1970, and soon afterwards full restoration of the whole estate began. Some of the furniture is original but, as at Palmse, many pieces have been brought from other houses that were not restored.

Allow time for a leisurely walk in the park behind the house. It contains what is probably Estonia’s tallest oak tree (about 33m in height) and also exhibitions of contemporary sculpture.

Altja

The fishing village of Altja is 8km from Sagadi. It has never been much more than a hamlet but it suffered under the Soviet regime when fishing, its sole livelihood, was banned and the population dropped from around 120 to merely 20. Subsistence farming was hardly a substitute as only potatoes could grow in the sandy soil and the grazing lands supported only a minimal number of cattle or oxen.

Fishing is now being revived and the excellent inn, which tourist groups use for lunch, provides employment during the summer. The mashed potatoes, with a diversity of ingredients always added, are the highlight of a meal here. Although outsiders, even Estonians, were not allowed access to the coast at that time, restoration of the wooden buildings started in 1971. The inn dates from the early 19th century and, for most of its life, women were not admitted except on 25 March, Lady Day.

Off-the-beaten-track highlights

In the central provinces

Around Gavar

The most important site in the vicinity of Gavar is the field of khachkars at Noratus but for those who enjoy visiting small village churches there are a number of some interest in and around Gavar. Although the churches are often locked the key holder can usually be found or will soon appear, having spotted visitors arriving. In the southern suburb of Hatsarat are two adjacent, well cared for, working churches, 9th-century Mother of God and 19th-century St Gregory. (The road to the churches goes west off the Gandzak road where the latter makes a right-angle turn.) The Mother of God Church, entered from St Gregory, is a domed three-apse church. St Gregory is a three-aisle basilica with very narrow side aisles. The front of the bema has khachkars. The gravestones in the cemetery around the churches have interesting carvings, including men on horseback, deer, horses, animals fighting, flagons and people with musical instruments.

Going southwest from the Gandzak road the very rural village of Tsaghkashen (when I was there water still had to be collected from a standpipe) has the church of St John (9th–10th century). Externally the church has a rather curious appearance, four wings of rough stone around a central rectangular red tuff upper part surmounted by a small belfry. Inside it is a four apse church, elongated north to south, with a central dome and a wooden balcony in the west. Obviously a much used church it is festooned with pictures and other offerings. Gandzak, just south of Gavar, has two small churches, St George (9th–10th century) and the small Mother of God (4th–5th century). St George has been restored externally and has a new roof with a small belfry perched on one corner. Inside it is in some ways a typical village zham its wooden pillars holding up a temporary hardboard ceiling when I was there. However its blue, white and red paintwork, the paintings on the walls and the delightfully uneven bema fronted by khachkars make it a ‘one-off’.

There is a large tombstone among the stone floor flags, which seems to be that of a person of significance. Both doors have carved lintels. Mother of God Church has also seen some restoration and now has a corrugated iron roof. Its floor level is significantly below present ground level and the eastern apse is very obviously an addition to a previous rectangular building; given its age this may well indicate conversion from a pagan to a Christian shrine. Some 10km further south is Lanjaghbyur village. On the steep hillside behind the village is the tiny restored 7th-century chapel known as Ilkavank and above it, on top of the hill, a 70ha cyclopean fort. Neither the chapel nor the fort of themselves justifies the detour unless you are particularly interested in such places but it does make a good walk and the views across the plain to the Geghama Mountains are splendid. If you go quietly you may spot one of the foxes which seem to favour these cyclopean forts. The track from the village to the chapel goes up through the cemetery.

Karmirgyugh, southeast of Gavar, also has two restored churches. Mother of God Church has a bell tower on its south side and another small belfry on the roof. Internally it looks as if what is now the chancel, to the east beyond the stone balustrade, was once a small cross-dome church with the typical stone columns and arches which would have supported a dome. The west part of the church is a typical zham with pairs of wooden pillars supporting the wooden ceiling. Externally the new walls show no east/west division apart from the fact that only the western part has windows. Within the bell tower the south portal has old masonry with carved details. Inside the church, khachkars, some of them painted, have been incorporated into the walls. St Gregory is built of rougher boulders which are also visible inside in the wide apse.

A painted khachkar in Mother of God Church, Karmirgyugh © Deirdre Holding

About 14km south of Gavar a small church can be seen on a knoll near the lake. It marks the site of Kanagegh medieval settlement and a cyclopean fortress. The remains of both cover a vast area; khachkars, two small churches and innumerable low walls, some in concentric circles near the lake, can be seen. Walking across the grassland to a headland overlooking one of Lake Sevan’s attractive bays gives some idea of the size of the settlements. There are no signposts but a church symbol appears on the most recent maps.

According to the plaque on the church it was renovated in 2000 by one Surik Jraghatspanian. Inside are before and after photographs and the church is surrounded by khachkars. The second church remains in a more ruined state but it too has had some restoration. Entering through the low door one finds oneself in a tiny but typical zham with wooden posts supporting the wooden ceiling all protected by a corrugated roof. The well-kept interior has a large stone in front of the small bema, such stones said to be an indication that the site was originally a pagan shrine, later converted for Christian use. In this small church the past can somehow be felt. The new cross outside commemorates the renovation in 2008 ‘in honour of St George’.

In the northern provinces

On the way to Lake Arpi

On the way north to Lake Arpi there are sights of some interest, all of which can be combined with a walk which can be as long or short as you wish to make it. This is a particularly attractive option in spring or early summer when the whole countryside is awash with the colours of an amazing variety of wild flowers.

At Hoghmik a Hellenistic site has been excavated on a small plateau above a tributary of the Akhurian River. There is not a lot to see apart from low walls, floors and fragments of columns but the complex is thought to have been a 6km long complex of three temples along with their associated buildings, fields and villages. Ceramics, altars and statuettes were found during excavation. Part of the pleasure for me lay in walking through the masses of early summer wild flowers then down a grassy track and along the river. Later in the year when the vegetation has died it might not be so colourful but the excavation would be easier to see. The site is 800m east of the leaving Hoghmik sign.

Colourful flowers at the Hellenistic site of Hoghmik © Deirdre Holding

The village of Tsoghamarg is on another tributary of the Akhurian River. Follow the turn-off as it bears right into the village. Immediately obvious is a roofless, black and red tuff village church or zham. It is of no particular interest although it does have some carving on its south façade and still has the wooden columns and roof beams typical of such churches. More interesting are the four ancient graves just northeast of the church and now within a small building which the villagers built in the 1960s to protect what they regard as a holy place, akin to a Tukh Manuk shrine.

The four graves are massive stone sarcophagi, thought to date from somewhere between 4,000–1,000BC but little is known about them. Immediately above, on top of the plateau, is a small cyclopean fort which can be reached by a 15-minute scramble up the steep, rocky slope. A gentler route is via the small ravine to the left as you face the cliff. Once on top not only is one rewarded by the fort, its size and easily traceable walls making it more comprehensible than some larger cyclopean sites, but there is often a pleasant breeze. The plateau is a good place for a walk, either along the small ravine or along the edge of the cliff with good views across the village to the hills to the south.

Perhaps even older and certainly just as mysterious are the megaliths near the village of Hartashen. Thought to date from 6,000BC, two lines of three long parallel rows of standing stones, all inclined downhill, stretch across the hillside in regular formation, one line half way up the hill following the contour, the second triple row lower down the hill and at a right angle to one end of the upper series, although not contiguous. The road I took to reach them was through the old village of Zuygaghbyur (in the few references to the stones they are called the Zuygaghbyur megaliths) but it may be easier to reach them from the Vardaghbyur turn-off.

Mysterious lines of standing stones – the Zuygaghbyur megaliths © Deirdre Holding

(Note that the Zuygaghbyur village marked on the Collage maps to the east of the main road is ruinous. The present day village of the same name lies on the main road just north of the turn-off for the old village.) The configuration of the stones reminded me of anti-tank defences I had seen in Estonia and, interestingly, some villagers are reported to have said that their grandparents erected the stones. Early 20th century or 6th millennium BC? Mysterious megaliths, indeed!

Northeast from Ijevan

Continuing south the main road winds up and down the hills with views across the plains of Azerbaijan. Here it is easy to appreciate that historically Armenians inhabited the hills and Azeris the plains. From the village of Tsaghkavan a very bad dirt road (parts of which are impassable even for a 4×4 with high clearance and mud-terrain tyres) leads to Shkhmuradi Monastery (or Getakits), about 6km from the main road. An alternative to walking through the woods is to contact one of the local farmers, Farmer Ararat, on his mobile phone (094 554786) who, if he is free, is willing to take two visitors there on his SAME German tractor. The ride takes about 45 minutes perched on the slippery mudguards of his tractor and you have to hold on very tightly. He asks just for the cost of fuel but it seems appropriate to add something more for his time away from his farm. Even if walking, a local guide is advisable.

The overgrown monastery is picturesquely situated below towering rock faces amidst the forest. Were it not that the main church abuts the road it would be easy to miss it. Most of the buildings are below road level. What looks at first like a grassy mound to the west of the church is in fact the roof of a gavit. There are no written records about the monastery apart from inscriptions on the buildings themselves. Descending round the end of the gavit, whose south door is blocked off, one enters the Mother of God church, built 1248, on its south side through a smaller, ruined second gavit which has an interesting khachkar with several human figures. The church is a cross-dome church of yellow felsite. From its west end steps lead down to the larger gavit. The earliest building, the Khoranik of 1149, lies to the east of the smaller gavit, only its west and north walls still standing. It was a single-aisle vaulted basilica with an east apse.

In the southern provinces

The large village of Angeghakot (7km west of the western entry road to Sisian), overlooking the Shaghat Reservoir on the Vorotan River, must be a cartographer’s nightmare. Streets seem to go in all directions in this ancient settlement of low houses, haystacks and khachkars but it is possible to find the most interesting features by doing a big loop through the village. The asphalt road from the highway becomes the dirt road which runs along the top of this long village. On entering the village, turn left to reach the large open area in front of the post office. Apart from a small modern cemetery with a statue of Zoravar Andranik, and one semi-derelict building, the open space, once a cemetery, is bare.

Angeghakot Reservoir from the Mother of God Church in Angeghakot village © Deirdre Holding

Old gravestones are dotted around, some still upright in the ground, some piled up with junk in corners, some used as seats in warm weather. There were once seven churches, most of which are now totally ruined. Two still stand. Continue downhill from the post office to the gorge. Where the road bends sharply right a path leads down through rocks to the medieval church of St Stephen, rebuilt in the 17th century. The single-nave church of rough stones is built up against the hillside. The road continues to the Mother of God Church a short distance away on the edge of the plateau. The three-aisled barrel-vaulted basilica (5th-century, several rebuildings and recent restoration) is built of rough stone inside, dressed stone outside. The roof, with a small central belfry, has been turfed for protection. If the church is locked the key is available from a nearby house if the keyholder is at home.

Continuing uphill the road brings you back to the west end of the top road on which you reached the village. The main cemetery (on the northwest edge of the village), with burials from the Bronze Age to the present day, is up a narrow track off this road (third left, if I remember correctly, but ask for the gerezman). There are some unusual gravestones. The most striking is a three-tier memorial which has what is thought to be a christianised vishap for its base, surmounted by a stone with an eye-hole, topped with a small khachkar.

Nearby is a khachkar on a seven-stepped pedestal and base with carved sun symbols, thought to be the grave of a Syunik prince. It is surrounded by other graves, some of which are also unusual: recumbent slabs with disc-shaped stones at each end. Carved with both the Armenian swirling eternity symbol and the star of David, they are believed to be the graves of members of a Jewish community who served rulers in Syunik and Vayots Dzor. There are khachkars carved from earlier eye-hole stones, and tombstones with a variety of carved human and animal figures.

Pärnu

Admitted to the Hanseatic League in 1346, the Estonian port city of Pärnu for many centuries rivalled Tallinn and Riga, but since the 19th century has been better known as a health centre and seaside resort, as well as for its yachting harbour. It has long been the go-to summer destination for locals, thanks to its long, sandy beach, relaxing spas and vibrant nightlife, but its medieval centre is also worth a stroll.

What to see and do in Pärnu

Rüütli Square

Where Rüütli and Ringi meet is now Rüütli Square but the 40 years of its previous life as Lenin Square needed to be obliterated. The building on the left side of the square, now shared between several banks, was the last in Pärnu to be completed in 1940 before the Soviet invasion. From the end of the war until 1967, the first floor served as a temporary theatre. It now houses the Museum of New Art, which moved here in December 2020 and has a small permanent collection but concentrates on temporary exhibitions, each lasting about four months.

Straight ahead is a monument unveiled in 2009 to commemorate the first signing of the Declaration of Independence, which took place in Pärnu at the Endla Theatre on 23 February 1918, a day before it did in Tallinn. The monument displays the full text. To the right of the Pärnu Hotel, on the corner of Rüütli and Aia, note the model of the former Endla Theatre which stood on this site before the war. Built in 1911, it had been the best example of Jugendstil in Pärnu, and could have been restored after bombing but was totally destroyed by the Soviets because of its association with the founding of Estonia.

Koidula Museum

Estonia’s most famous man, pre-war president Konstantin Päts, and Estonia’s most famous woman, the 19th-century poet Lydia Koidula, both went to school in Pärnu. Koidula became a household name during the national awakening of Estonia and her school has since been transformed into a museum about her life.

Located in the house where she lived from 1850 to 1863 (her father Johann Voldemar Jannsen worked as a schoolmaster at the time), this is a useful place to learn about their lives and activities in the context of national awakening, all while gaining a deeper insight into the traditional settings of 19th century Estonia. The statue of her made in 1929 was the last work of sculptor Amandus Adamson who died that year.

Pärnu Yacht Club

The town council granted permission for the building of the first bathing centre in 1837 but support was so poor that in 1857 public bathing on the beach was banned in the hope that this policy would force more people to use it. Fortunately the council realised at the turn of the century that Pärnu needed to cater for the healthy as well as for the sick.

The park was laid out, the yacht club established in 1906, and between the wars it attracted many foreign visitors. By 1938, over half of the 6,500 summer tourists were from abroad, Finns and Swedes replacing the Russians as there was a ferry service each summer between Stockholm and Pärnu. The yacht club closed during the Soviet period but is now thriving again.

Concert Hall

Pärnu’s pride and joy, the Concert Hall opened in the autumn of 2002. Although famous for the music that is offered year-round, Pärnu has never before had a suitable venue for orchestral music and opera.

For the €5.75 million it cost it is a real bargain, and, as it is a circular glass building, Estonians can see both by day and by night what activities their taxes are generating. Had the world-famous conductor Neemi Järvi not lobbied and given constant support to the project, it might never have gone ahead.

The main auditorium seats a thousand and can be easily adapted for choral or theatre performances; it can equally be turned into a private ballroom. The higher floors are a music school. Neemi Järvi’s extended family is as musical as the Bachs and many of them participate in the annual David Oistrakh Festival in Pärnu each July. Future programmes at the concert hall can be seen on the website.

Elizabeth’s Church

Walk along Rüütli into the Old Town taking the second road on the left, Nikolai, and the Baroque façade of Elizabeth’s Churchon Kuninga comes into view. It was built between 1744 and 1747 and is named after the Russian empress on the throne at that time.

It has two links with Riga: the spire was designed by the architect Johann Heinrich Wilbern, who designed the spire of St Peter’s, and the organ, installed in 1929, is the work of Riga’s most famous organ builder of that time, Herbert Kolbe. It was restored in 2013. The statue on the corner of Kuninga and Nikolai is of Georg Richmann (1711–53), one of the pioneers in the discovery of electricity and probably the first scientist to be killed experimenting with it. His eyes light up at night.

The Red Tower

Just off Hommiku, on the west side of the road, is Pärnu’s oldest extant building, the Red Tower, which dates from the 15th century. As its thick walls and deep basement suggest, it was a prison for much of the time since then. It housed the town archives from World War I until 1972, after which it was largely empty. Fortunately, it reopened in 2020 as a cinema in the round, with a 10-minute 360° film, which skilfully summarises Pärnu’s 11,000-year history.

Alevi Cemetery

The Alevi Cemetery is where all the great and the good from Pärnu are buried, but what is surprising is how simple all their tombs are, and very few have statues with them.

Oskar Brackmann’s has a line from a Goethe poem Überallen Gipfeln ist Ruhe (Beyond the peaks, there is calm) famously set to music by Franz Liszt, amongst many others. The Ammende family who built the grand hotel that carries their name are buried together but there is no hint of the exuberance here that characterises the hotel.

Amandus Adamson lies behind the Independence Monument he built for the cemetery and which of course was destroyed in the Soviet period. It had to be rebuilt from his designs and photographs that fortunately remained. The monument is now surrounded again by tombs of those who fought for Estonian freedom in both world wars.

Tallinn

The departure board at the airport lists London, Copenhagen and Stockholm but rarely St Petersburg. The boats that fill the harbour, be they massive ferries or small yachts, head for Finland and Sweden, not Russia. The traffic jams that are beginning to block the main streets are caused by Volkswagens, Land Rovers and Audis, not by Ladas. Links with the West are celebrated; those with Russia are commemorated.

Tallinn was always ready to defend itself but in the end hardly ever did so. Only for 16 years, between 1561 and 1577, were its fortifications put to the test, when the Swedes, Danes and Russians all attacked the city. The nearest it came to what might have been a major battle was at the conclusion of the Northern War in 1710, but plague had reduced the population from 10,000 to 2,000 so the Swedes offered little resistance to the army of Peter the Great. Tallinn has suffered many occupations but, apart from a Soviet bombing raid in 1944, the city has not been physically harmed as no battles were ever fought there. Its fate was always determined elsewhere, in the 14th just as much as in the 20th century. Only after 30 years of independence is Tallinn firmly in its own hands.

The division in Tallinn between what is now the Old Town on the hill (Toompea) and the newer town around the port has survived political administrations of every hue. It has divided God from Mammon, tsarist and Soviet governors from their reluctant Estonian subjects, and now the Estonian parliament from bankers, merchants and manufacturers who thrive on whatever coalition happens to be in power.

Tallinn has no Capitol Hill or Whitehall. The parliament building is one of the most modest in the Old Town, dwarfed by the town walls and surrounding churches. When fully restored, the Old Town will be an outstanding permanent monument to Gothic and Baroque architecture, and a suitable backcloth to formal political and religious activity. Outside its formidable wall, contemporary Tallinn continues to change rapidly according to the demands of the new business ethos.

Visitors returning to Tallinn who had previously been in the 1990s will today be surprised at how much time they want to spend outside the Old Town. Areas such as Telliskivi and Noblessner, both Soviet slums for all too many years after re-independence, are now each worth a day in their own right for their cultural and gastronomic diversity, highlighted by Fotografiska in the former and Proto in the latter. On the edge of the Old Town is the rejuvenated Rotermann Quarter. Its sleazy past was brought to life in 1979 by the film The Stalker, the last one made in the Soviet Union by Andrei Tarkovsky before he came to the West. Today, however, the area is keen to flaunt its luxury status, perhaps appropriately as it borders on Tallinn’s Wall Street.

There is a legend that, should Tallinn ever claim to be ‘complete’, the monster in Lake Ülemiste next to the airport, will flood the town. But now, more than ever, Tallinn continues to expand, outwards and upwards.

What to see and do in Tallinn

Alexander Nevsky Cathedral

Entering the cathedral represents a symbolic departure from Estonia. No-one speaks Estonian and no books are sold in Estonian. It is a Russian architectural outpost dominating the Tallinn skyline and was built between 1894 and 1900, at a time when the Russian Empire was determined to stifle the burgeoning nationalistic movements in Estonia.

It was provocatively named after Alexander Nevsky, since he had conquered much of Estonia in the late 13th century. The icons, the mosaics and the 15-ton bell were all imported from St Petersburg. Occasionally plans are discussed, as they were in the 1930s, for the removal of the cathedral as it is so architecturally and politically incompatible with everything else in Toompea, but it is unlikely that any government would risk the inevitable hostility that would arise amongst the Russian-speaking population of Tallinn.

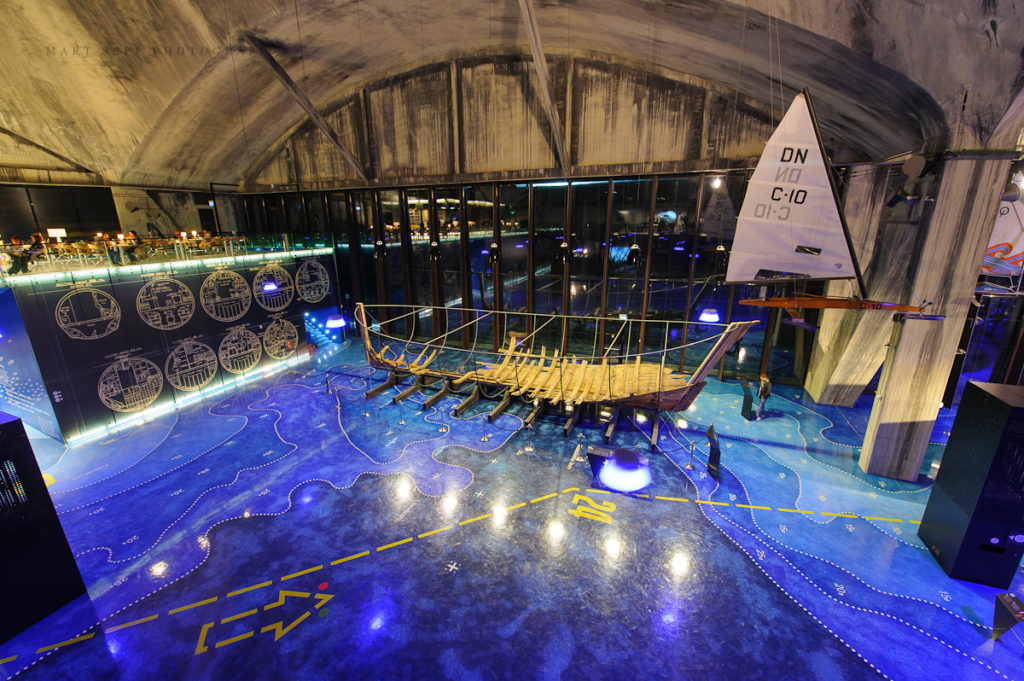

Seaplane Harbour

Since the spring of 2012, one of the highlights of a visit to Tallinn has been the complex next to Patarei Prison, which opened in May that year. The basic structure of the hangars dates from 1916, when they were commissioned by the tsarist Russian government from a Danish company, Denmark being neutral in World War I. Such was the strength of the concrete with which it was constructed, that the building survived intact for the next hundred years and was happily exploited by each new army of occupation throughout the 20th century.

There is an instant impression of 3D on entering the building, as it is necessary to look up, ahead and down at the same time to gauge the true effect of the collection. A walk begins on a bridge above most of the collection, in the air as it were, looking down on the boats at surface level and the submarines below it, with planes directly ahead and on both sides.

Old Town Hall

This was the administrative and judicial centre of the town until 1970 and the extensive range of woodwork and paintings in the Council Chamber mainly reflects judicial themes. Six centuries of Tallinn’s history have been determined in this room and it is only since 1991 that its use has changed to a purely ceremonial role, with visitors allowed to tour and concerts taking place here.

For much of this time, there were clearly ample funds in the public Treasury, as is shown by the opulence of the candelabra, the money chests and the size of the wine cellars. One of the carvings of David and Goliath on the magistrates’ bench is often taken to symbolise the relationship between Tallinn Council and its nominal masters on Toompea in the Old Town.

Tartu

Unlike Tallinn or Pärnu, Tartu is not a town of instant charm. Arriving by any of the dreary approach roads does not suggest the imminence of a famous university town or of one where Estonia gained its statehood. Yet intellectually and architecturally it is the centre of Estonia. Its university cultivates an Oxbridge/Ivy League tradition but has combined it with the radicalism of Berkeley or the London School of Economics.

Estonia’s most famous scientists studied and taught here and its most famous patriots, whether in opposition to the tsar, the pre-war president Konstantin Päts or the Soviet regime, likewise spent their formative years in Tartu. The 200km distance from Tallinn suited both sides. Political activists could be more daring and the government could feign liberalism, safe in the knowledge that its detractors would not be a threat to the capital. With independence and democracy now safe in Estonia, Tartu is taking up new causes.

The celebration in October 2007 of the 375th anniversary of the founding of the university, which was attended by Queen Silvia of Sweden, was a great incentive for renovation in the Old Town. It was also around that time Tartu realised, if it was to be a successful second city, it would need to be a business centre as well as an academic one and had to compete with Tallinn as a base for Estonian and international companies. It has been successful, particularly with start-ups; Playtech and Nortal are among the larger companies based here, with the former now listed on the London Stock Exchange. On the cultural side, the opening of ERM, the National Museum, in 2016 gave the town further prestige and excellent publicity.

Tartu now has a diverse programme of festivals that take place all year round except in July and August (when the hotels fill up anyway). If it matters whether you turn up for the cross-country ski marathon, the break-dancing finals or student rag week, check their dates here. This also gives the programme at the Vanemuine Theatre, which spills out on to the Town Hall Square (weather permitting) during the summer.

A full day is needed to cover the town centre and the university, and a further half day to visit a selection of the museums. The parks beside the river offer relaxing walks and concerts in the summer.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Estonia:

Related articles

Celebrate the festive season the Estonian way.

Find out how to walk on the wild side in this forested Baltic nation.

Rest, rejuvenate and recharge.

Shining a spotlight on sustainability.

Perfect for any hopeless romantic seeking an escape away from the crowds.

Explore two of Tallinn’s most vibrant and creative districts.

There are many national parks in Europe that remain fairly unknown. Here you can discover 14 of the best. Why miss out on visiting somewhere spectacular?