Flanders surprises at every turn. Its main cities are epicentres of culture and you could easily spend all your time visiting just these. But where possible, take the time to explore the outer towns and villages away from the regular tourist trail – they give an excellent insight into real Flemish life and its driving values.

Emma Thomson, author of Northern Belgium: the Bradt Guide

Most people think they have Flanders – the Dutch-speaking northern half of Belgium – figured out: beer, chocolate and the EU are the standard tag lines.

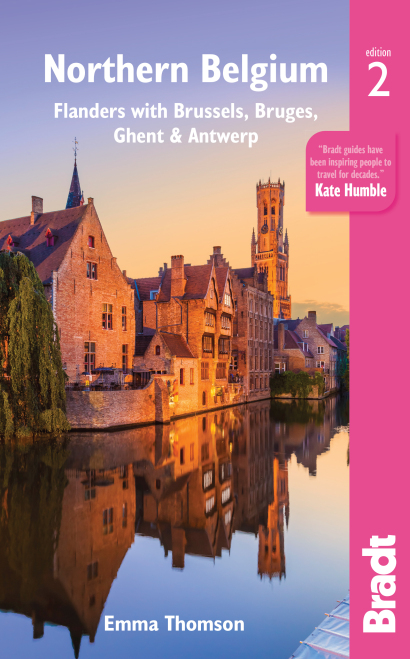

Once labelled ‘boring’, the region is now being radically reappraised thanks to its refreshing mish-mash of buzzing cosmopolitan cities and relaxed rural villages, which allow travellers to visit UNESCO-listed highlights such as Brussels’ Grand’ Place or Bruges’ romantic canals one day, and snug off-the-beaten-track sites like the bewitched village of Laarne the next.

Flanders’ appeal lies in its ability to really satisfy life’s fundamental desires: thirsts are quenched (or should we say drenched) with the choice of over 400 beers, hungry tummies are filled with Europe’s most-respected cuisine, and eyes can feast on the works of world-renowned artists and cartoonists.

Dig beneath the surface and you will discover a region of quirk and style, whether it’s sampling the world’s rarest beer in a time-forgotten estaminet, or spending the night in a traditional begijnhof. Prepare to develop a life-long devotion to Europe’s most underrated region.

For more information, check out our guide to Northern Belgium:

Food and drink in Northern Belgium

Flanders might be best known for fries, beer and chocolate, but foodies have long since cottoned on to its dense concentration of Michelin stars – there are more starred restaurants in Bruges alone than in the whole of Denmark – and this trickles down to a huge glut of high-class bistros and, latterly, street-food pioneers reinventing traditional snacks. It’s quite possible to let your nose and appetite guide you around the region, sampling fresh fish on the North Sea coast and beer-soaked stews in cosy, wood-panelled establishments in the countryside. When all this can be washed down with award-winning beers or a cheeky shot of jenever, the appeal of Flemish dining is irresistible – gastronomes prepare to let a notch out of your belt.

Food

When it comes to dining, there are two types of Flanders meals: traditional meals based around meat and fish – often filling fodder that would have kept farm hands happy until dinner time in the old days – and the entirely different experience offered by fine-dining restaurants, which proliferate in villages, suburbs and cities. National favourites are undoubtedly steak-frites – the meat is of high quality and usually from a local butcher – and mosselen-frieten/moules-frites; mussels and other shellfish are in season between September and March, or – according to the adage – any month whose spelling contains an ‘r’. In winter, the Flemish like to tuck into witloof in de oven (chicory wrapped in ham and covered in a creamy cheese sauce); waterzooi (a broth containing fish/chicken and vegetables); stoemp met prei (mashed potato mixed with leeks); stoofvlees (beef stew made with brown beer); konijn en pruinen (rabbit cooked with prunes and beer); and paling in ’t groen (young eel cooked in a green sauce of spinach, sorrel, mint, thyme, tarragon, bay leaf and white wine).

Belgian waffles need no introduction and come in two varieties: the Brussels and the Liège. The latter (and tastier) is a dense, doughy mixture laced with sugar and served piping hot. The yeast-leavened Brussels variety, on the other hand, may contain fewer calories but is similar in weight and taste to polystyrene, perhaps the reason why they cover it in icing sugar, chocolate sauce, ice cream or fruit. Also look out for the marzipan-flavoured mattentaart , cinnamon-flavoured speculaas biscuits and Diksmuide’s custard-filled IJzerbollen. Most cities produce chocolates referencing the nickname of inhabitants.

Drink

Beer is to Belgium, what wine is to France – a daily essential, with UNESCO recently recognising Belgium’s entire beer tradition – from the brewing to the drinking – as a slice of intangible cultural heritage. The two have a long and distinguished relationship and it’s invariably the first word people associate with the country. With over 800 varieties, the production and consumption of beer are a source of national pride and their breadth and quality have had beer aficionados fizzing with delight for years. Like a fine wine – and treated with the same respect – the majority of these beers should be sipped slowly and savoured, which is no bad thing when alcohol percentages reach 12%.

Also high in the alcoholic stakes is jenever, a juniper-flavoured spirit unique to Flanders and the Netherlands. Traditionally developed from the distillation and fermentation of malt, this liver-warming shot drink comes in two varieties: oude (old) and jonge (young). In fact, the differentiation has nothing to do with age, but rather varying distillation recipes; younger jenevers are made from grain and are served chilled, tasting similar to vodka; old jenevers have a higher concentration of malt, are aromatic like whisky and are served at room temperature. Alcohol percentages range from a hefty 20% to a toe-curling 40%. Hasselt is particularly renowned for its production and has a dedicated museum.

Surprisingly, Flanders also has a modest sprinkle of vineyards, including Genoels-Elderen on the outskirts of Tongeren, and award-winning DIY outfit Schorpion, situated just outside Hasselt and renowned for its sparkling and white wines.

Health and safety in Northern Belgium

Health

There are no official vaccination requirements for entry into Flanders and no serious health issues to worry about. However, it is best to be up to date with the vaccinations recommended for Britain such as diphtheria, tetanus and polio – now given as the all-in-one vaccine Revaxis – that last for ten years and MMR. There has been an increase in the number of cases of measles in Europe so ensure that you have either had measles, mumps and rubella (the diseases) or have had two doses of the MMR vaccine. Other vaccinations would include hepatitis B for health-care workers, plus influenza and pneumococcal vaccines for the elderly and those at special risk. If you are walking in long grass, check yourself for ticks afterwards; they may carry Lyme disease which manifests as a rash accompanied by a fever, headache, neck stiffness, painful muscles and joints, swollen lymph glands and fatigue. It is treatable with antibiotics if it is recognised at an early stage.

Safety

Flanders is safe to visit. Like most places there are instances of bag-snatching, pickpocketing and very rarely mugging, and you should be vigilant if walking late at night in the vicinity of Brussel Zuid/Bruxelles Midi and Brussel Noord/Bruxelles Nord railway stations. As long as you aren’t flashing huge sums of cash or leaving valuables exposed in the back seat of your car, you shouldn’t encounter any problems. Nonetheless it’s a good idea to make photocopies of your important documents, and to store them separately from the originals.

Terrorism

There have been a number of high-profile attacks in recent years conducted by terrorists linked to Daesh, most notably on 22 March 2016, when coordinated attacks killed 32 and injured hundreds at Brussels Airport Zaventem and on the capital’s metro system. Brussels’s profile as the ‘capital’ of Europe and HQ to numerous international institutions like NATO and the EU will continue to make it vulnerable, but with a stepped-up police presence at transport hubs and in major cities, there’s absolutely no reason to avoid travelling to Belgium or to feel unsafe once there. In fact, it’s worth taking a leaf out of locals’ notebooks: in the wake of an anti-terror lockdown in Brussels, when requested not to give away the police’s positions, residents took to posting (often defiant) pictures of cats online instead!

Travel and visas in Northern Belgium

Visas

Citizens from Ireland, EU countries, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the US do not require a visa to enter Belgium and are permitted to stay for 90 days, as long as you have three months left on your passport. If your country does not appear in this list, then you must apply for a visa.

Getting there and away

Flanders is incredibly accessible. Bang in the middle of Europe and hugging the North Sea coastline, it can be reached by air, sea or land. It also helps that Brussels is a major international business hub and, as a result, transport links have increased to meet the demands of countless international commuters. Companies are battling to provide competitive fares and travellers can benefit from these price wars.

By air

From the UK and Ireland

You can fly direct from London, Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol and Edinburgh, and, in Ireland, direct from Dublin. Flights from the UK take about an hour; those from Ireland an hour and 40 minutes.

Brussels has two major airports: Brussels Airport Zaventem and Brussels South Charleroi Airport. Zaventem is 13km northeast of Brussels and served by most major airlines, including national carrier Brussels Airlines. Outer-lying Charleroi is 60km south of the city, or around an hour’s drive away, and serves budget airlines.

From the US and Canada

Direct flights from the US to Brussels are no longer hard to find, and there are also direct links from Canada. The most competitive rates start at just over US$300 for a week-long trip. Brussels Airlines (see above) serves Brussels from New York, Washington, DC and Toronto. Other companies flying direct to the Belgian capital include Air Canada from Montreal, United from New York, Chicago and Washington, DC; and Delta from New York and Atlanta. On average, flights from the east coast of the US and Canada to Brussels take around 7 hours.

By Eurostar

Eurostar runs up to ten services a day from St Pancras International to Bruxelles Midi/Brussel Zuid; the journey time is about 2 hours. There are three classes of ticket: Standard; Standard Premier, which includes a light meal; and Business Premier, which you can change or cancel for free. The cheapest returns start at £58; standard singles can run as high as £170 if booked last-minute. You can buy an ‘Any Belgian Station’ ticket for a small supplement, which includes an onward journey within Belgium; high-speed trains such as Thalys aren’t included, and if you are heading to Brussels Airport Zaventem you’ll have to pay a €5.25 ‘Diabolo’ supplement each way either at a Belgian station or on board. They frequently run promotions combining rail travel and hotels, so check their website. For flexible travellers, Eurostar Snap, launched in 2016, offers discount rates as low as £50 return. You can specify the day of travel and whether you want to leave in the morning or afternoon; 48 hours before departure, you will get an email with your allocated train. It’s the luck of the draw so be prepared to travel at dawn or late; check their website for the latest promotions.

By ferry

Travel by boat has been heavily eclipsed by the faster Eurostar and Eurotunnel services, but if you’re not in a rush, cross-Channel ferries can offer savings, especially for families. P&O runs services from Dover to Calais, and an overnight service from Hull to Zeebrugge (the only UK to Belgium crossing now), while DFDS Seaways sails from Dover to Calais and Dunkirk.

By car

To reach Belgium from the UK by car, either take a car ferry or Eurotunnel. This high-speed car train runs from Folkestone to Calais 24 hours a day, with up to four departures an hour during the day and every couple of hours between 23.00 and 06.00. The journey takes 35 minutes, then from Calais it’s a 2-hour drive along the E40 to Brussels; De Panne is just 50 minutes away.

By bus

If you’re prepared to put in the bum-numbing hours, Eurolines, a division of National Express, offers daily departures from London Victoria coach station to Brussels and Antwerp. The journey takes 8½ hours, with fares from £30 return if booked well ahead. Cheaper still is German company Flixbus, launched in 2013 to rival state railway Deutsche Bahn. It connects London and Bruges twice a day, taking a mere 6 hours; it also has daily services to Ghent, Antwerp and Brussels, and is useful if you’re on a wider European jaunt, with direct links from Flanders to Paris, Amsterdam and beyond. UK–Belgium routes start from £9.99 for a single journey.

Getting around

The public transport system in Flanders is exemplary. Trains and buses service every corner of the country and, what’s more, they nearly always arrive on time.

By car

Belgian drivers get a lot of bad press and I’ve certainly seen evidence to back this up, but on the flipside, Belgian highways are some of the best in Europe, are toll-free and, until energy-saving measures were put into place, so well lit at night that you could see them from space. Naturally, you will encounter some common irks, which include getting stuck in traffic jams during the summer exodus for the coast and driving in cities riddled with one-way systems. Then of course there are the road signs that switch from one language to another. However, with a little preparation and bravado, travelling by car will give you the freedom to drive off track and discover sights, or that special restaurant, that would otherwise pass you by as you stare out of the window of the train.

By train

Trains are operated by the excellent national railway company SNCBNMBS, with services starting at 05.00 and ending at midnight. Tickets may be bought online, or at the station; avoid the premium for buying them on board if you can. Fares are relatively low. Antwerp to Poperinge, for instance, which is one of the longest direct journeys in Flanders, costs €21 one way; Ghent to Brussels is €9. It’s worth planning trips for the weekend when return tickets are half-price (you must depart after 19.00 on Friday). Those under 26 can travel anywhere in Belgium except Brussels Airport Zaventem for €6.60 each way, while seniors (aged 65+) pay only €6.80 for a same-day return anywhere in Belgium, as long as they leave after 09.00 on weekdays. Up to four children under 12 also travel free when accompanied by an adult. Seats cannot be reserved. Most stations have coin-operated luggage lockers. Bicycles are allowed on trains; buy a one-trip card (€5) or day card (€8). Folding bikes are free.

By metro, tram and bus

All three are operated by De Lijn in Flanders and STIB-MIVB in Brussels. Tram systems operate in Brussels, Ghent, Antwerp and on the Flemish coast. Unless you are heading to out-of-the-way attractions, or on a very tight budget, you will probably not need the bus, which works in harmony with the rail network. In all cases, you can buy tickets from dedicated kiosks, from automatic ticket machines or on board, though you will pay a premium for this. A day pass (dagpas) or multi-day pass is usually the cheapest option for travellers. Once on board, you will need to validate your ticket by punching it in the yellow machines situated at the front and by the doors.

By taxi

Stands can be found outside most railway stations, airports and hotel entrances; drivers rarely do random street pick ups. Fares are based on a meter; they begin with a fixed charge of €2.40 at the start of the journey (this increases at night) and are then calculated at around €1.80/km within the Brussels Capital Region and €2.70 elsewhere.

When to visit Northern Belgium

Flanders is best visited during spring and summer, or just before Christmas. From March to May the countryside is alive with newborn lambs and calves, and orchards are filled with blossom; July and August are marked by an impressive array of music and folk festivals and parades; and come December romantic Christmas markets line cobblestone squares. There are a few provisos: avoid the coast during winter when it becomes a series of ghost towns whipped by gale-force winds and rain; and be aware that from mid-November to February many of the smaller towns – and the World War I memorial sites – tend to go into hibernation; and that in July and August you’ll be battling the selfie sticks in Bruges, so plan your trip accordingly.

Climate

Notorious for its four-seasons-in-one-day climate, Flanders lies on the same latitude as the south of England and experiences similar weather patterns – it is luck of the draw as to whether it will be a summer of heatwaves, or one of endless rain, though the latter has tended to dominate of late (just don’t say global warming). Between spring (Mar–May) and autumn (Sep–Nov) you can expect temperatures to fluctuate between 14°C and 6°C and cool, sunny days to be intermingled with overcast, drizzly days. During summer temperatures hover around the 20°C mark, but in winter (Dec–Feb), when the Baltic breezes come whistling down uninterrupted from the North Pole, temperatures plummet, rarely rising above 6°C and occasionally dropping to –5°C. However, even the darkest days have their splendour, and the changeability of the weather is better than solid grey. And, there’s something incredibly romantic about dashing from café to café across soaked but sparkling cobblestone streets.

As a guide, July tends to be the hottest month, January the coolest, November the wettest and February the driest. During summer, the sun rises between 05.00 and 06.00 and doesn’t set until 22.00. During winter, the days shorten considerably – sunrise is between 07.00 and 08.00 and sunset between 16.00 and 17.00.

What to see and do in Northern Belgium

Aalst Carnival

This relatively tourist-free folkloric feast dates back to the Middle Ages, when local rulers allowed the townsfolk to enjoy three days of no-rules debauchery prior to Ash Wednesday, the start of Lent. A word of warning: be prepared to party – this is a non-stop knees-up (think Rio Carnival on a Flemish scale) but it’s not just that, with UNESCO recognising the event’s intangible cultural heritage in 2010.

In 1851 townsfolk introduced the procession of flotillas that parade through town and mark the arrival of carnival. Local groups spend months preparing these floats, which take the mickey out of local figures and recent events – eg: a former mayor’s holiday indiscretions or, in 2016, a float with a Trump-esque character demanding a wall between Aalst and Dendermonde (at Dendermonde’s expense, of course)!

The procession starts on the Sunday/Monday before Ash Wednesday and ends with Aalst dignitaries throwing thousands of onions from the balcony of the town hall into the crowd, including one lucky golden onion. Tuesday is Voil Jeanetten – sure to stir up conversation. Men arrive dressed in stockings, corsets and birdcages, and stumble around on high heels drunkenly embracing each other (it’s a nod to Aalst’s working-class roots – in decades past, men couldn’t afford fancy costumes, so dressed in their wives’ old schmatters). As evening falls, everyone gathers on the Grote Markt and, with genuine tears of remorse, watches the Carnival Prince light a bonfire, signalling the end of the party.

Brussels

A capital, an independent region, an island in a language-divide dispute, the centre of Europe and the seat of the European Union – Brussels wears many hats. Which side you see depends on the purpose of your visit, but most agree that the city is initially something of an enigma – and it’s still common to hear people invoking its supposedly ‘boring’ reputation.

Situated at the centre of a cultural crossroads of Latinate and Germanic traditions, and home to 1.2 million people – almost 70% of whom are of foreign descent – Brussels is, perhaps surprisingly, the second most cosmopolitan city in the world after Dubai. Not classically chic like Paris, or hip and stately like Berlin, it can be hard to pigeonhole – much like its architecture, which is a mishmash of historic buildings and ultra-modern constructions. But conventional beauty is banal and Brussels’s trump card is its multi-cultural make-up and small scale. Often described by residents – known as Zinnekes – as a village, Brussels is compact, easy to get around and not overwhelming like most European capitals.

It may be introverted – shy to share its secrets with those who live there, let alone with visiting strangers – but therein lies the appeal. All romantics know the exhilaration is in the chase and what better thrill than to pace her streets in search of what makes Brussels tick? Look among flea markets and award-winning kitchens of passionate, headstrong chefs, hang out in glorious Art Nouveau cafés and amble through intriguing residential communes. I guarantee that underneath the calm and composed surface you’ll find the heartbeat of a city with an unmistakably Bohemian, eclectic spirit.

Lier

It’s a hard heart that isn’t charmed by Lier. This small town, equidistant between Antwerp and Mechelen, is officially older than Brussels, having received its town charter in 1227, 15 years prior to the capital. It was also the stage for one of the most famous marriages in history. To prevent arguments breaking out between the competing cities of Ghent, Brussels, Bruges and Antwerp, it was decided that Philip the Fair and Johanna of Castille would marry in Lier. The story goes that they fell in love at first sight – she was 16, he was 18 – and Philip insisted that the marriage took place that very evening, presumably so the lustful teenager could consummate the marriage as soon as possible! Among their six children was Charles V, who would rise to become Holy Roman Emperor.

The town has a strong association with lace – between 1820 and 1950 3,000 women were employed at home making it – and you can watch local lace-making clubs hard at work in the pretty béguinage. You also shouldn’t miss Lier’s pride and joy, a 90-year-old clock tower known as the Zimmertoren. If you can, visit in spring when the surrounding orchards are in full bloom and a racing-pigeon market animates the Grote Markt on Sundays (until mid-April) – such markets are very rare these days.

Lissewege

Just north of Bruges, Lissewege is a tiny conglomeration of whitewashed cottages nestled around an ancient Gothic church. It’s one of Flanders’ prettiest villages and home to a close-knit community of 2,400 inhabitants. However, this number can seem considerably greater during summer when groups of locals and tourists stop off for lunch during cycling tours of the surrounding polders, or potter about open-air exhibition Statues in the White Village, when over 100 artists create works strewing Lissewege’s most picturesque spots. Visit at the beginning of September when the season is dying down and you’ll be able to wander its cobbled streets in peace. I guarantee you’ll start enviously eyeing up the Te Koop (‘For sale’) signs in some of the cottage windows.

Mechelen

Mechelen (Malines in French) is one of Flanders’ most underrated cities, and as the seat of the archbishop, it is to Belgium what Canterbury is to the UK. Equidistant between Brussels and Antwerp, it might be overshadowed by its neighbours now, but in the late 15th century it was the most important town in the southern Netherlands. Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, established parts of his administration here in 1473; future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V lived here as a child with his aunt Margaret of Austria, under whose governorship the city peaked. Its glow faded when Margaret died in 1530, and the royal court moved to Brussels. Mechelen later reinvented itself as Belgium’s ecclesiastical hub; more recently it has won plaudits for its integration policy under Bart Somers, who was voted World Mayor of the Year in 2016, owing to his success at uniting 86,000 inhabitants of 138 nationalities. While it is a manageable day trip, Mechelen merits a longer stay: with more UNESCO sights than any other art city in Flanders, it’s home to atmospheric museums and restaurants – and two important, albeit dark, World War II sites.

Ooidonk Castle

People come from far and wide to visit Flanders’ most complete, and beautiful, castle. Surrounded by a moat and rich woodland, Ooidonk Castle once belonged to Philippe II de Montmorency-Nivelle, also known as the Count Hoorn, who was executed on Brussels’s Grand-Place alongside Count Egmont for resisting Spanish rule. The castle suffered extensive damage during the religious wars of 1579 and was rebuilt in the Flemish-Spanish style you see today. You’re free to wander the lovely gardens all week, but the interior is only open at weekends because the current owner, Henri t’Kint de Roodenbeke, still lives in the castle. Its collection of period furniture, paintings, tapestries and silver is sumptuous.

While in the area, we highly advise stopping off for creative Flemish classics at restaurant Bachtekerke, whose tree-lined terrace on the banks of the Leie river was voted the best in Belgium by Gault&Millau in 2018.

Oostduinkerke

Quaint and quiet Oostduinkerke is famous for its paardenvissers (horse fishermen), who trawl the shallows at low tide fishing for the grey North Sea shrimp used in dishes like tomates-crevettes. Today, despite numbers dwindling to three fishermen in living memory, and despite global warming bringing unwanted jellyfish and other catch close to the shore, Oostduinkerke is the only place in the world where the tradition lives on, hence UNESCO designating it as intangible cultural heritage in 2013. From spring to autumn, ruddy-cheeked, bearded fishermen (and, nowadays, one or two beardless fisherwomen) wearing yellow oilskins and sou’westers ride hefty Brabander horses up to their chests into the muddy North Sea. For 2 to 3 hours they wade up and down the beach pulling nets behind them and occasionally coming ashore to empty their catch into the wicker baskets slung either side of their saddles.

Tongeren’s antiques market is one of Europe’s finest © Jeroen Broux, VisitFlanders

Tongeren

Flanders’ oldest city, Tongeren was home to the Eburones, a Gallic tribe who protested furiously when the Romans arrived and tried to take over. Their king, Ambiorix, rose to fame for his bravery on the battlefield and even impressed Julius Caesar, who described him in his memoirs as the ‘bravest of all Gauls’. Of course, this didn’t stop Caesar crushing the tribe and forcing them into slavery. Ambiorix managed to escape and, consequently, is embraced as a Flemish hero. The Romans named the town Atuatuca Tungrorum, and when Brussels was still no more than a few dirt lanes, Tongeren was a bustling Roman trading outpost connected to the imperial highway. It was also one of the first towns in the Low Countries to adopt Christianity after the appointment of Bishop St Servatius in ad342. Under the protectorship of Liège, it continued to thrive, allowing for the construction of the medieval city walls. However, a huge fire reduced the centre to rubble in 1677, and the town didn’t enjoy a revival until Belgian independence in 1830.

Today Tongeren is an instantly likeable place which has embraced its Roman history with gusto. It now boasts one of Europe’s best museums and the largest antiques market in Benelux (07.00–13.00), with 350 stalls and 40 shops spanning Leopoldwaal, Clarissenstraat and Maastrichterstraat on Sundays, and a huge covered antiques hall near the Moerenpoort. The tourist office has a free brochure pinpointing all the stalls. Expect to rub elbows with experts and amateurs from around the world.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Northern Belgium:

Related articles

Linger a while and you’ll find that the Belgian coast has a charm of its own.