Aimed at adventurous, possibly even eccentric, people of all ages and on all budgets, eastern Turkey really has something for everyone.

Diana Darke author of Eastern Turkey: The Bradt Guide

Even Turks themselves are only just starting to discover the beauties and mysteries of the eastern half of their own country. Little known and little understood, this staggering region east from the capital, Ankara, has been transformed in recent years by a wave of prosperity bringing with it new road networks and new boutique hotels and restaurants.

Accounting for over two thirds of Turkey’s landmass, but with less than half of its population, it has been the beneficiary of Turkey’s huge investment in development schemes, above all the series of 22 dams on the Euphrates.

Water is everywhere, in lakes, rivers and waterfalls, something that is especially clear when you fly into one of the many domestic airports, all of which are within two hours of Istanbul or 1½ hours from Ankara.

Security concerns are a thing of the past, when Kurdish guerrilla fighters of the PKK had regular clashes with the army back in the 1980s and 90s. But now, since 2000, you can travel freely, with no permits required except for the ascent of Mount Ararat itself, always granted as a formality.

Far removed from the cosmopolitan Istanbul and the bustle of the Aegean and Mediterranean coastlines, Eastern Turkey is like a country within a country. Wild and rugged, the Anatolian Plateau was home to civilisations of a completely different kind, all of whom left relics for exploration.

Early Christians escaping persecution carved out churches and entire cities underground; mountain Hittites and Urartians built fairytale castles on impossible crags; power-mad chieftains honoured themselves with fantasy palaces and colossal statues. Best of all, you can enjoy these sights untrammelled by over-development, with empty roads and a vast sense of space.

For more information, check out our guide to Eastern Turkey

Food and drink in Eastern Turkey

Food

No-one comes to eastern Turkey for the food, and while Turkish cuisine has been praised, even by French gourmets, as one of the finest in the world, sadly such praise rarely applies in eastern Turkey, where food is on the whole far more limited than in the rest of the country. Notable exceptions are in the extreme southeastern parts close to Syria, heavily influenced by Syrian cuisine, so in towns like Mardin, Midyat, Gaziantep and Antakya, there awaits you a gastronomic experience of a different order. Make the most of it, for as you head north and east, the food becomes increasingly basic and unvarying. Doğubeyazıt, at the foot of Mount Ararat, is known as the cheapest place to eat in all of Turkey, and quantity outweighs quality by a long way. Hors d’oeuvres or mezze, usually the highpoint of Turkish cuisine, are hard to come by except in the areas close to the Syrian border. Soup is usually the only thing on offer as the prelude to the main course. The common staples are as follows:

• Hot yoghurt soup with rice and mint (usually quite good)

• Tomato soup (very bland, a Heinz lookalike)

• Potato or lentil soup (variable, and best inspected before deciding)

• Lukewarm or cold green beans cooked in tomato sauce and grease

• Baked beans

• Chips or pilav rice

• Salads with tomatoes, cucumber, onion and green chillies

• Stuffed green peppers with rice and pine nuts (usually cold, and though rather greasy, not at all bad)

• Chicken cooked in grease

• Meat (mutton) stew with aubergine and okra

• Meat kebab, lamb or mutton (usually quite grisly)

• Trout (alabalık) plainly grilled or fried (available close to rivers)

• Rice pudding (strangely comforting)

• Crème caramel (usually very good)

• Baklava (not one for picnics – too sticky)

• Fresh fruit in season: strawberries (May), oranges and apples (late summer), guavas, green erik (a small sharp kind of plum), peaches and cherries (May and June)

• Nuts: pistachios are especially good in Gaziantep and Antakya

Drink

Like the food, all drink in Turkey, alcoholic or not, is very cheap. Ayran is the non-alcoholic national drink, a chilled unsweetened yoghurt liquid, thirst quenching and slightly sour. Rakı (a clear aniseed spirit similar to the Greek ouzo) is the national alcoholic drink, usually mixed with ice and water, which makes it go cloudy white. It goes well with Turkish food and is usually drunk with a meal, rather than on its own.

As befits the place where it is thought the grape was first cultivated, Turkey today has the fourth-largest area in the world under viticulture, and is the sixth-largest wine producer in the world. Very little of this wine is exported. On the red side the best is Buzbağ, a full-bodied red, closest to a Burgundy; other good reds to ask for are Yakut, Villa Doluca, Dikmen and Trakya. The premium whites are Çankaya, Villa Doluca, Kavalıdere and white Trakya. The locally brewed beer is the ubiquitous Efes, sold in cans and bottles. It is very refreshing and tastes like a kind of Pilsner lager.

While alcohol – spirits, wine and beer – is available in all the better hotels in the cities, around 70% of the local restaurants never serve it at all, and during the holy fasting month of Ramazan this percentage may go up to as high as 90%. If you want a drink with your food it is therefore best to check before ordering so that you are not disappointed once it is too late. Of the non-alcoholic drinks available, ayran and water are the most common, although cola and fizzy orange are usually available as well.

Health and safety in Eastern Turkey

Health

With a few sensible precautions most health problems can be avoided, and most people only experience a few minor things which can be easily treated with medicines you can carry with you. Sunstroke is the most likely thing to strike if you are travelling in the summer months, so make sure you always have your head covered with a proper rimmed hat and keep well hydrated. Use copious amounts of a broad-spectrum (UVA/UVB) sunscreen with an SPF of 15 or higher to avoid burning.

Stomach upsets are difficult to avoid in eastern Turkey so you should be careful about everything you eat and drink. Lomotil and antibiotics can be bought over the counter from the chemists’ shops (eczane) in all towns, but it is wise to consult a doctor before you go to check what is appropriate for you and buy before you travel. Always carry a few sachets of oral rehydration salts with you. In central Anatolia and Cappadocia standards of hygiene are higher so you are less likely to pick anything up until you hit the east proper, ie: Adıyaman and eastwards.

the summer months the dust can cause much discomfort to the eyes, with aggravated catarrh in the nose and sore throats. It is a good idea therefore to take eye drops and throat lozenges. Protect yourself from mosquito bites by using a DEET-based repellent, ideally containinig 50-55% as the optimum. This should be used during the day to prevent the risk of dengue fever and again at night to protect against malaria and to ensure a good night’s sleep.

Vaccinations

There are no certificate requirements for entry into Turkey, however some vaccinations are recommended to protect against certain diseases. It is wise to be up to date with diphtheria, tetanus and polio, which comes as an all-in-one vaccination: Revaxis. There is also a moderate to high risk of hepatitis A and therefore vaccination against this is also recommended for most travellers. There is a low risk of typhoid, but vaccination may be recommended to longer-term travellers in more rural areas.

Turkey is classified as an intermediate risk for hepatitis B. Vaccination would be recommended for longer term or frequent travellers, children and those working with children, people working in medical settings and those playing contact sport or other risky sports.

Turkey is classified as high risk for rabies and vaccination should be considered for all travellers if budget allows, as getting treatment is not always easy if you have not had the rabies pre-exposure vaccine before you go. Those handling animals are at highest risk, as are those who are in more remote parts of the country or who are travelling for a month or more. Hepatitis B and rabies courses consist of three vaccines given over a minimum of three weeks, so it wise to seek advice well in advance of your trip.

Safety

Eastern Turkey used to suffer from political instability due to problems with Kurdish insurgents but thankfully these problems have essentially been resolved and so travel in the region is now safe and easy. Everywhere is accessible and can be visited without restriction. Petty crime rates for such things as pickpocketing and car theft are very low, and there are too few tourists for the habit of overcharging foreigners to have caught on.

However, the region has had a history of violence between its various ethnic groups, which resulted in martial law being imposed by the Turkish government throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Very few foreigners get caught up in violent incidents, and if they do, it tends to be by accident. In July 2008 three German tourists were kidnapped by the PKK, a Kurdish separatist group, on the slopes of Mount Ararat, and released unharmed a few days later, an act of protest against the German government for its closure of PKK offices in Germany. Two people, both Turkish nationals, were killed in the Gezi Park protests.

Female travellers

Bus or long-distance coach is the best and safest way for solo women to travel round the country. Women travelling on their own should keep away from traditional male enclaves like the meyhane (wine house) and birahane (beer house), as their presence there drinking will be taken as an invitation for sexual attention. In cities where there is a university and therefore a student population there may be some Western-style barlar (bars) where it is acceptable for women to go for a drink if other female students are present.

Otherwise, you should bear in mind that gender segregation is much more prevalent in eastern Turkey than in the western parts of the country, and foreign women who drink too much in public will be regarded as conforming to stereotype and only after one thing. In Turkish baths, hammams, there are always separate times for men and women. Etiquette varies from hammam to hammam about whether or not you remove your underwear under your pestemal (short cotton sarong you are given), while men keep theirs on at all times. Carry a scarf to cover your head and shoulders on visiting a mosque and always dress modestly so as not to invite unwanted attention.

Body language is very important, especially eye contact. If you make too much direct eye contact with a male stranger it is seen as very forward and again, inviting attention. Try to learn therefore to make only as much eye contact as is necessary when buying tickets, food, etc, so that it is clear you are only interested in carrying out the task. Watch how Turkish women behave and interact with other men in public. Whether or not you get hassled as a female in Turkey (or any Muslim country) has nothing to do with how attractive you are. A blond blue-eyed woman for example will not get hassled if she behaves modestly and dresses and carries herself demurely, because her whole body language is conveying she is not available. It is best to be polite but distant.

Dress is important in the eastern provinces, and you should always make sure you are not scantily clad. Tight shorts and low-cut T-shirts are not at all appropriate and will cause offence. If you are decently dressed, covering bare flesh above the elbows and knees, and behave sensibly and discreetly, you will cause no offence but will simply be regarded with great curiosity by men and women alike.

Travelling with children

The family is very important to Turkish people and children of all ages are welcomed everywhere. This does not mean that society is child-centred, as nowhere will you find child menus or toys supplied. It is simply that they are accepted as a normal part of life, so adults can relax and enjoy themselves. Even very young children are taken out to eat in restaurants in the evening with their parents and amuse themselves happily with the forks and spoons on the table, eating small amounts of their parents’ food.

High chairs are a rarity, as young children either sit on an adult’s knee or are big enough to have their own chair. Formula milk and nappies are available now in the eastern regions, either at the budding supermarkets or at the pharmacies. Baby food in jars is not always easy to find, however, but restaurants and hotels will usually be happy to purée food for you. UHT milk is widely available in small cartons with a straw. Some hotels can provide cots if these are requested in advance, but standards vary quite widely, and sides can be lower than those common in the UK for example, making them fine for a baby but less suitable for a mobile toddler. Child car seats are not regarded as standard, so you should check with the car hire firm whether they can provide these on request.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Unlike in the rest of the Middle East, homosexuality is legal in Turkey (and has been since the Ottoman times). While it is tolerated in big cities like İstanbul and Ankara, however, in eastern Turkey it is a different story and you will need to be very careful in public, as there is still strong prejudice against both gays and lesbians. There are now a couple of gay-friendly travel agents such as Absolute Sultans and Pride Travel.

Travelling with a disability

In Turkey’s eastern regions, many Turkish cities, hotels and tourist sites have no wheelchair access, though Turks will always try their best to improvise and be helpful. A visit to eastern Turkey will therefore be very challenging to travellers with mobility problems, with virtually no adapted toilets, ramps or wide doorways. Turkish Airlines does, however, give a 25% discount to travellers with minimum 40% disability and their accompanying carer(s), but you need a doctor’s letter as proof at the time of booking. Ankara and Cappadocia do have better facilities, but it is best to check in advance via a tour operator.

There is one tour operator, Mephisto Voyage based at the İn Pension in Çavuşin, which can arrange special tours of Cappadocia for mobility-impaired people, using the Joelette system, a comfortable wheelchair on one wheel with adjustable treadle, head- and foot-rest.

Travel and visas in Eastern Turkey

Visas

A new system of e-visas (electronic visas) was introduced in April 2013, and all nationalities who require a visa can now apply online at www.evisa.gov.tr. In order to apply you need your passport details, flight details and a MasterCard or Visa credit card for advance payment. Once your visa has been approved, you must print it off in order to show it to passport control on arrival in Turkey. Applying online avoids the sometimes-lengthy queues to buy a visa on arrival, but it costs more for non-American travellers at a flat US$20 irrespective of nationality. Your credit card will take an equivalent amount and convert it for you. The visa is still multiple entry and valid for three months.

Ordinary British passport holders can still buy a visa costing £10 on arrival at a Turkish airport, and this visa is multiple-entry and is valid for three months. Nationals of Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Netherlands, Norway (one month only), Portugal, Spain and the USA have the same arrangement, though the amount varies from country to country (Americans pay US$20 for example) and it must be paid for in hard currency notes, not coins (US dollars, euros or pounds sterling). You have to queue first to buy your visa stamp at the separate kiosk before queuing again at passport control. This has to be done at the first point of landing in Turkey, so even if you are transiting directly to an airport in eastern Turkey, you will still need to queue for your visa first before transiting to the domestic terminal for your onward flight, unless you already have your e-visa. Nationals of Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Sweden and Switzerland do not require a visa at all. Tourist visas do not give the right to take up employment, whether paid or unpaid, to reside or to study (excluding student exchange programmes), or to establish a business in Turkey.

Getting there and away

By air

Flights to İstanbul from London take around four hours and arrive either at Atatürk International Airport which is on the European side of the city, with onward domestic flights leaving from the Domestic Terminal, a short walk away, or at the newer but smaller Sabiha Gökçen International Airport on the Asian side. Whilst Sabiha Gökçen is further from the historic centre of İstanbul and therefore less convenient if you are having a stopover, flights to it are often cheaper and if you are planning an onward flight the same day it can end up more convenient for transiting. Its small size makes it very user-friendly and there are fewer queues.

Eastern Turkey has domestic airports at Adana, Adıyaman, Ağri, Batman, Diyarbakır, Elâzığ, Erzincan, Erzurum, Gaziantep, Hatay (Antakya), Kahramanmaraş, Kars, Malatya, Mardin, Muş, Samsun, Şanlıurfa, Trabzon and Van. All these have flights linking to İstanbul and Ankara, and sometimes in season from Izmir or even Antalya, making two-centre holidays within Turkey entirely feasible. İstanbul’s Atatürk International Airport is 30–40 minutes’ drive away from Sultanahmet, İstanbul’s tourist centre and where the Blue Mosque, the Aya Sofya and the Topkapı Palace can be found.

The most popular scheduled service carriers to Turkey from the UK are the national carrier Turkish Airlines, British Airways, Pegasus Airlines and easyJet. These fly from London’s airports (Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted) but Turkish Airlines also operate a direct flight from Birmingham, and Jet2 flies to İstanbul from East Midlands, Leeds Bradford, Manchester and Newcastle airports. Germanwings is a low-cost airline based in Cologne that operates from several German airports to İstanbul (Sabiha Gökçen) and Ankara. The Spanish airline Spanair flies from several Spanish airports to İstanbul’s Sabiha Gökçen airport.

By sea

The only ferry services to eastern Turkey are the regular services to and from Girne (Kyrenia) in Northern Cyprus and Taşucu near Silifke, from Girne (Kyrenia) to Alanya (summer only), and between Mersin and Gazimağusa (Famagusta). You can arrive in western Turkey by car ferry from Piraeus in Greece at Ayvalık, Çeşme, Bodrum or Marmaris. Direct car ferries from Italy to Turkey no longer run, though you can link from Brindisi or Bari in Italy to Patras in Greece, then drive on to Piraeus.

By train

There are direct sleepers running once a day from Serbia (Belgrade, taking 22 hours), Greece (Thessaloniki, taking 11 hours), Bulgaria (Sofia, taking 15 hours) and Romania (Bucharest, taking 19 hours) into İstanbul run by the Turkish State Railway. Fares range from TRY75 to TRY300 depending on whether you just have a seat or a first-class couchette. Once a year in August the ultra-luxurious Venice–Simplon Orient Express runs a six-day trip to İstanbul. This service sells out very quickly so early booking is recommended. All trains coming from the west arrive at İstanbul’s historic Sirkeci station on the Golden Horn, just a short distance from Sultanahmet, where İstanbul’s main sights are concentrated. Haydarpaşa station on the Asian side is currently closed due to work on the high-speed rail link between İstanbul and Ankara, which is scheduled to continue until 2014. The Trans-Asya Ekspresi to Tehran in Iran will start at Haydarpaşa once engineering works are complete, but currently starts at Ankara, running weekly on Wednesdays via Kayseri and Van, and taking 66 hours. Consult www.rajatrains.com (the Iranian railways site) or www.seat61.com for details of these services, which also involve a five-hour crossing of Lake Van.

By bus

Regular coach services run to Turkey from Bulgaria, Romania, Germany, Austria, Italy, Greece and Holland to the west, as well as Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Iran and Syria to the east (see www.eurolines.com). The most comfortable and direct services run from Italy, Germany, Austria and Greece, with a direct route between Vienna and İstanbul taking 27 hours, and a direct route from Athens to İstanbul taking 20 hours. These routes are operated by Ulusoy and Varan Turizm using large Mercedes coaches which are hard to beat. All buses (both international and domestic intercity) arrive into the colossal Esenler Coach Station (just known as the otogar) in the northwest of İstanbul, about 10km from Sultanahmet. The cheapest way into Sultanahmet is to catch the LRT (Light Rail Transit) service from its otogar stop to Aksaray, then catch the metro from the Aksaray stop to the Sultanahmet stop. The whole journey takes 30 minutes and costs TRY5. By taxi it costs about TRY35 and takes around 20 minutes.

By car

You can drive your own car to Turkey via Bulgaria or Greece. Your vehicle is allowed to stay in the country for up to six months after entry. At the border you will need to provide a valid passport, national driving licence, vehicle licence, international green card (insurance card) and vehicle registration document. Make sure your vehicle insurance is valid for the Asian side of the country. If you want to keep your car in the country for longer than six months you will have to pay import tax. For further information consult the Turkish Touring and Automobile Club. The drive from the UK to Turkey is about 3,000km and the two common routes are a) the northern route via Belgium, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria and b) the southern route via Belgium, Germany, Austria and Italy, with a ferry to Patras or Igoumenitsa in Greece, then onward to Turkey via Piraeus.

Getting around

By air

Tickets are best bought online using a price comparison website or direct through one of the airlines. The usual system applies whereby the cheapest tickets are available a couple of months in advance, so the earlier you book the better. Tickets can also be bought on the spot in the Domestic Terminal, although this is risky as the flights are often full.

The national carrier Turkish Airlines (Türk Hava Yolları; www.thy.com) flies at very reasonable prices between all the main cities of eastern Turkey, namely Adana, Adıyaman, Ağri, Batman, Diyarbakır, Elâzığ, Erzincan, Erzurum, Gaziantep (Antep), Hatay (Antakya), Kahramanmaraş (Maraş), Kars, Malatya, Mardin, Muş, Samsun, Şanlıurfa (Urfa), Trabzon and Van. All these cities have flights at least once or twice a day linking them to İstanbul and Ankara. The flights range in time between one and two hours, bringing even the remotest corners of eastern Turkey within easy reach. In the summer high season there are also an increasing number of connecting flights to the eastern airports to and from Izmir and Antalya, making two-centre holidays within Turkey a realistic option.

By train

The rail network in Turkey was constructed in the late Ottoman period, mainly by the Germans, and often follows a mysterious routing system, said to be because they were paid according to the distance. Newer, more direct lines are currently being laid.

All onward travel from İstanbul used to be from the historic Haydarpaşa station, Kadıköy, a gift from the German Kaiser to the Ottoman Sultan in 1908. This station has been closed since 2012, however, while the new high-speed line to Ankara is being constructed and it may never be reopened. A new station, 25km east of İstanbul called Pendik, is planned for 2014 or 2015 and eventually, a year or two later, this will link to a new station in central İstanbul via the new Bosphorus rail tunnel. The high-speed İstanbul to Ankara express train will take just six hours.

Until all the work is completed, you can take a ferry from İstanbul (Kabataş terminal) to Bursa, and then link up with the high-speed Bursa–Ankara train, or alternatively take a bus from İstanbul to Eskişehir, where there is a high-speed train line to Ankara.

By coach and bus

This is by far the most popular and convenient way to travel by public transport inside Turkey. Every town and city has its own bus station (otogar) with many routes linking every corner of the country, many frequent services and many companies to choose from, each varying slightly in frequency and comfort. The competition between them means that the system is efficient and cheap. Some of the biggest names are Kamil Koç, Metro, Ulusoy and Varan. Varan and Metro have an online reservations service so you can even book tickets from the UK, something that is otherwise extremely difficult to do unless you speak Turkish. Tickets can usually be bought on the day at the bus station, where each bus company has its own office, though at weekends or on public holidays it is advisable to book in advance. Specific numbered seats are allocated, so to ensure the best position on the bus you can buy your ticket a day or two in advance. The middle seats are generally considered to be the best, as the ride can be bumpy towards the front or rear. Bus companies also have central offices in cities and large towns where tickets can be bought.

By taxi and dolmuş

Taxis are always yellow. Although meters are usually fitted in eastern Turkey, they sometimes do not work, so it is wise to agree on the fare first. If you are travelling outside the city boundaries it is usual to agree a fixed rate in advance. The dolmuş is a shared taxi, usually a minibus, sometimes a large car, which follows specific routes within larger towns and cities, picking people up and setting them down anywhere along the route. It is recognisable by its yellow band. The word dolmuş means literally ‘stuffed’, from the fact that they do not follow a set timetable but simply set off when they are full. The fares are fixed by the relevant municipality, and each passenger pays according to the distance travelled and can get out at any of the specified stops. Much cheaper than a private taxi, it is often good to take a dolmuş from the airport to the bus station or to the centre of town. As well as linking the city centres with the suburbs, there are also some intercity dolmuş services, but these are more expensive than the bus and often less comfortable.

By bicycle

Eastern Turkey is a good place for cyclists (Bettina Selby did it alone in 1992 and wrote her book Beyond Ararat, Mountain House Publishing 1993), as roads are often empty and little used. In Cappadocia there are already plenty of places hiring out bicycles, a perfect way to explore the lesser-known valleys. It is possible to take your own bicycle on Turkish trains and buses as long as you have notified the train or bus company in advance. On buses they will put it in the baggage compartment underneath with all the other luggage (so beware of possible damage), and on trains they will put it in a baggage compartment, assuming the train has one. Often it is the slower trains that have them, not the faster trains with Pullman seats and couchettes, so check in advance direct with the station concerned if you speak Turkish or else via an agency like Tur-ISTA. On ferries you can just wheel it on and off yourself. A good map for cyclists is available in İstanbul bookshops, it is called Köy Köy Türkiye Yol Atlası.

By car

Travel by car is by far the best way of exploring Turkey. Without one you will be able to see less, or you will need more time (adapting your plans to bus schedules, etc) to see everything. The roads in central Anatolia and eastern Turkey are usually very empty. Many places in eastern Turkey lie off the main roads, making them difficult to reach with public transport. Having your own car is therefore a huge help and saving in time, and sometimes even in cost if you are travelling in a group of four, say. Another saving if travelling by car is that you can stock up with suitable picnic food and drink and keep it in the boot, so that you are not dependent on finding somewhere to eat during the day. You can also keep to your own timetable. The number of private cars on the road is still quite small in relation to the number of buses and trucks, due to the high price of cars in the country. The area where you do get heavy traffic is on the main transit highway from Ankara south through Aksaray and Pozantı to Tarsus, along the coast to Adana, Gaziantep, Şanlıurfa and Nusaybin, where the transit route enters the eastern corner of Syria or border crossings to Mosul in Iraq.

When to visit Eastern Turkey

When to visit

The best time to visit the eastern Turkey is between April and September, with June probably the best month of all for most places. Even then, you should be prepared for a huge diurnal range, with temperatures between day and night routinely differing by over 20ºC, and your clothing needs to take account of this. The main tourist season runs from 1 April to 31 October, and the heavy winter snowfall means that many of the smaller hotels and pensions close from November to March. Ramazan, the Muslim month of fasting, is probably best avoided in eastern Turkey, as it is more strictly observed than in the Aegean and Mediterranean parts, and you may find it difficult to find places to eat during the day.

The high-summer months of July and August are extremely hot during the day, with temperatures often reaching 40ºC, though it still drops sharply at night. Cities close to the Mediterranean coast like Adana and Antakya are also very humid in high summer, and air conditioning in your hotel room becomes something that can make a big difference to your night’s sleep. The Black Sea swimming season is from June to early September, though the weather is not as dependable as the Mediterranean, with far heavier rainfall.

In the winter months some parts can be especially attractive, notably Cappadocia and Lake Van, when the snow enhances the landscapes and there are still clear bright days to be had. Temperatures of –30 to –38ºC are possible during the daytime up on the Anatolian Plateau and temperatures of –20 to –25ºC are normal from December to February, so your clothing needs to reflect that, but the roads are mainly kept clear by snowploughs, with only the highest of passes (above 2,000m) closed for the winter, and even then only on the more minor roads. If you want to avoid the crowds and pretty much guarantee having the place to yourself, the winter may be the time to come, as long as you do not want to climb any of the volcanoes or visit Nemrut Dağı, which, at 2,150m, is inaccessible because of snow from November to April.

Climate

Extremes of temperature are the order of the day in eastern Turkey, not just between winter and summer, but also between night and day. This is because of the presence of mountain ranges close to the coast and the great height of the interior plateau ranging from 800m to 2,000m. The most dramatic example of this is Kars, in the northeast, where the highest temperature recorded has been 35ºC in the daytime in summer, and the lowest –37ºC at night in winter. These enormous seasonal variations are among the widest in the world. Rainfall too is extremely variable.

Along the eastern Black Sea coast towards the Georgian border, over 2,500mm fall per year, while parts of the central plateau, shut off by the mountains from the influence of sea winds, are arid, with annual rainfall less than 250mm. Temperatures around the coast are a little more clement, both on the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, but the Anatolian Plateau of the interior, raised up at around 1,500m and exposed to the full harshness of the elements, bears the brunt of the severe weather extremes. For more information about travelling by boat, check out Gulet cruises Turkey.

What to see and do in Eastern Turkey

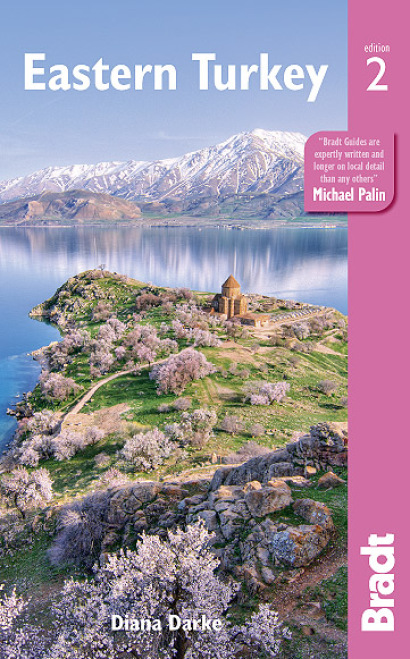

Armenian Cathedral Church of the Holy Cross on Akdamar Island © MURAT KARSLI, Shutterstock

Akdamar Island and Lake Van

No-one forgets Lake Van. Make sure you spend at least three days around the shores of this, Turkey’s biggest lake, seven times bigger than Lake Geneva, enjoying the water and the scenery and visiting the castles, churches, mosques and tombs left round its shores by earlier civilisations. May and September are the best times to come. In winter from mid-October to mid-April it is too snowbound to be able to enjoy it properly. The high summer months of June, July and August are the best for climbing in the area however, so if you want to scale the two huge volcanoes that stand on the northern and western shores, Nemrut Dağı (not the same as the more famous mountain sanctuary of Antiochus further west, though sharing the same name) and Süphan Dağı, come then. These require camping on the mountain, so at least three further nights are necessary. The area has almost unlimited hill walking opportunities, where the goal can be a remote mountaintop Urartian citadel or a ruined Armenian monastery long abandoned in the wilderness. Until the mid 1960s this whole region was a restricted zone which no-one could enter without special permission. The roads were unspeakable then, and terrible in the 1980s, but they are very good now, so moving about has been transformed.

The serenity of the lake hides its troubled history well. The Hurrian ancestors of the Hittites were the first rulers here in the 2nd millennium BC. It was the Urartians, however, coming from the south and the southeast around the great Zab Valley in the Hakkâri region, who created the greatest empire and period of stability, ruling from 900BC to 500BC. Their civilisation only began to be truly appreciated in the 20th century with the excavation of their hilltop citadels and palaces and the discovery of their beautiful gold artefacts.

A century ago the shoreline was much more wooded and green, but man has left his mark and only very few wooded stretches now remain. Cuneiform documents dating back to the Assyrian invasion here in the 8th century bc talk about cutting down forests as dense as rushes. ‘Van in this world, Paradise in the next’ is the old Armenian proverb that summed up the once-legendary fertility of this region. In some of the villages however, like Adilcevaz, there are still excellent fruit trees, especially apricots. Van was also where the cantaloupe melon originated. The pope in Rome once had a farm of his own called Cantalupo and he imported Van melons to grow on it. From there they spread all over the world as cantaloupes.

Ankara

As Turkey’s modern capital, Ankara has many new roles, and it is the interplay and conflict of these roles that makes the city so intriguing today. When Atatürk moved his headquarters here in 1919 at the start of the War of Independence, it was a deliberate distancing from cosmopolitan İstanbul, a statement that Turkey was much more than its Ottoman past. Ankara then was a small town of only 30,000 inhabitants. Now official UN figures for 2013 estimate it is a metropolis of nearly five million, making it Turkey’s second-largest city, but still a long way behind İstanbul’s 14 million. It may be a modern city today, but its origins go back to the 2nd millennium bc when it was a Hittite settlement called Ankuwash.

It is fitting therefore that the two major sights Ankara has to offer reflect both its ancient and its modern ties: the spectacular Museum of Anatolian Civilisations and the Cyclopean Anıt Kabir, Atatürk’s mausoleum. One day should be sufficient to visit Ankara’s attractions. In fact, in an energetic half day you can visit the museum (two hours), take a brief stroll around the medieval citadel (45 minutes), then visit Anıt Kabir (one hour), have lunch and set off for the Hittite heartlands, with the museum still fresh in your mind.

© NikoNomad, Shutterstock

Cappadocia

Cappadocia, this region of strange rock formations and painted cave churches was largely forgotten by the Western world until 1907, when a visiting French priest, Guillaume de Jerphanion, decided to devote the rest of his life to the study of its churches, publishing his vast research in the 1930s and 1940s. Since then the renown of the area has spread worldwide and Cappadocia has become one of the most visited and photographed areas of Turkey.

It is probable that even in pre-Christian times the rural population of Cappadocia made use of natural caves. They were easily extended, with the soft rock so readily carved out that early Christians would have found them ideal for hiding from pagan persecution. The area became an important frontier province during the 7th century when the Arab raids on the Byzantine Empire began. By now the soft tufa had been tunnelled and chambered to provide underground cities where a settled if cautious life could continue during difficult times. When the Byzantines re-established secure control between the 7th and 11th centuries, the troglodyte population surfaced, now carving their churches into rock faces and cliffs in the Göreme and Soğanlı areas, giving Cappadocia its fame today.

Their churches and monasteries were many and small: the landscape was suitable for recluses in search of the spiritual life, and the region was distant from the contending doctrines of orthodox Constantinople and Monophysite Syria. St Basil, a 4th-century Father of the Church from Caesarea (Kayseri), opined that small and disciplined communities were most conducive to religious feeling. At any rate here they flourished, their churches remarkable for being cut into the rock, but interesting especially for their paintings, relatively well preserved, rich in colouring, and with an emotional intensity lacking in the formalism of Constantinople; this is one of the few places where paintings from the pre-Iconoclastic period have survived.

Icons continued to be painted after the Seljuk conquest of the area in the 11th century, and the Ottoman conquest did not interfere with Christian practices in Cappadocia, where the countryside remained largely Greek, with some Armenians. But decline set in and Göreme, Ihlara and Soğanlı lost their early importance. The Greeks finally ended their long history here with the mass exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey in 1923.

Gazīantep

This northeast corner of Turkey from Mount Ararat up to the Black Sea coast boasts some of the most spectacular scenery anywhere in Turkey, with magnificent, heavily forested mountains, serene lakes and beautifully green and lush valleys. Water gushes everywhere and this is the place for Turkey’s white-water rafting fraternity. The Kaçkar Mountains offer fantastic trekking landscapes, and much of the scenery in the Georgian valleys is reminiscent of the high Alps in summer with green meadows covered in tiny brightly coloured flowers. The difference is the buildings, for nowhere in the Alps will you find the ruins of Armenian churches and monasteries tucked away in remote valleys, or castles in black basalt perched on hilltops.

Allow a minimum of two nights in this area if you plan to pass through quickly, staying one night at Kars while you visit Ani, the Armenian ghost town right on the Armenian border, and one night in the Artvin area while you visit Georgian churches, before continuing your itinerary onwards to the Black Sea coast. To do it justice, however, you could easily spend a week or more, especially if you want to do some trekking in the Kaçkar Mountains. The main city of the northeast, Erzurum, has some interesting Islamic monuments, but can be safely bypassed if these do not appeal.

Göbekli Tepe

‘First came the temple, then the city’.

These are the words of the German excavator in charge, Dr Klaus Schmidt. Pre-dating Stonehenge by 6,000 years, Göbekli Tepe is a remarkable site, enclosing the world’s oldest known temples, and it has turned our perceptions of man’s early history upside down. The world’s earliest known city, Çatalhüyük, also in eastern Turkey, has been dated to 6000BC, a full 3,000 years later.

Although excavations started in 1994, and have continued every year since, only 10% of the site has so far been uncovered. It is likely to stay that way for some years to come, as Dr Schmidt has said he will leave the rest of the site for future generations since there is more than enough to keep him busy for the rest of his life in what he has already discovered. Schmidt happened upon the site in 1993 after he had been working on the Neolithic site of Nevalı Çori before it was lost to flooding – the result of the Ataturk Dam being built on the Euphrates. He currently works on the site from February to June, and late September to early December, making these the best times to visit, both to coincide with the excavations and the cooler weather.

Evening over Mardin’s old town © muratart, Shutterstock

Mardin and the Tûr Abdin

Mardin

Mardin is 96km south of Diyarbakır. As you approach from the north, the modern town now sprawls unattractively over the hill before you can see why you have come here, but be patient. You must continue right up on to the rocky crag where old Mardin sits, perched, facing south over the Syrian Desert. Only then do you begin to catch glimpses of the beautiful stone-carved and decorated mansions, Arab-style, which are Mardin’s real attraction. Some are almost like palaces, hinting at the past splendour of the town, though unfortunately many ugly modern buildings have recently been allowed to insert themselves. Back in the 1980s many of the old houses were decaying, but now a significant number have been restored and put to use either as museums or as plush hotels or restaurants.

Mardin generally has cleaned up its act, and the squalor of the back streets 20 or 30 years ago is a thing of the past. The Turkish government is promoting Mardin to both Turks and foreign visitors, and projects an optimistic five million per year visitors within the next ten years. Tourism here needs to be handled sensitively, otherwise Mardin is in danger of becoming overpriced and over trendy. Allow at least half a day here to appreciate it properly, either overnighting here or at Deyrulzaferan, the nearby Syriac Orthodox monastery, if you have set it up in advance.

The Tûr Abdin

The Tûr Abdin translates literally as ‘the Servants’ Plateau’, but the French phrase it more elegantly: ‘Montagne des Serviteurs de Dieu’. This highland region east of Mardin and with Midyat at its centre is the heartland and homeland of the Syriac Orthodox Church. A stay of several nights would be warranted in this region to visit the fascinating mix of monasteries and churches, some still functioning, some ruined, which are scattered about the landscape, often in defensive positions on hills or cliffs. The final monastery is listed under Midyat.

Sometimes known as Jacobites, they owe their founding to Jacob Baradai who, in the 6th century, was sent to Antioch by the Monophysite-leaning Empress Theodora, wife of Justinian. From there he roamed for 35 years, dressed only in a horsehair blanket, preaching and converting across Syria and the Tûr Abdin.

Among the legends associated with the region is the one that Noah’s Ark came to rest on Mount Kadur (also known as Mount Cudi), which rises to 2,114m east of Cizre and opposite the town of Şırnak (rather than on Mount Ararat, the more popular story). The name of Şırnak is a deformation of Şehr-i Nuh, meaning City of Noah. At any rate, Noah’s grave in Cizre is a point of pilgrimage for Christians and Muslims alike. From a base of Mardin, the excursion to Deyrulzaferan, the closest to Mardin and most westerly of the monasteries, takes half a day.

Mount Ararat

From afar the slopes of Mount Ararat look deceptively easy to climb, but in practice the jagged lava fields are very tricky to negotiate, and significant numbers have been killed in the ascent. Long considered impossible to climb by local people, it was first climbed in 1829 by a German, Professor Parrot, on his third attempt, and then by a steady trickle of German, Russian, British and most recently Turkish mountaineers. All ascents were still discounted by both local Kurds and Turkish officials until the 1950s, and even today some villagers do not believe it is possible to ascend the mountain.

Political problems dogged the area for most of the 20th century, and before 1982 there were no more than a handful of successful ascents, many of them illicit. The base of the mountain’s cone covers an area in excess of 2,500km, a fact which helps us to understand why, in summer 2008 when the PKK kidnapped three Germans from Camp 1 at 3,200m and hid with them on the mountain for ten days, the Turkish military had no chance of finding them, or indeed of sealing off the mountain.

The risk of kidnap by Kurdish separatists is small, but when times are tense, the Turkish authorities close the mountain to climbers. It was closed for several years in the 1990s, but reopened in 2000. It has generally stayed open ever since, apart from the occasional short closure, such as the six-week closure that followed the kidnap of some German climbers in summer 2008. Whole communities of Kurdish nomads live on the lower slopes of Ararat in the summer months, below 3,200m, either in villages or in tented encampments with their livestock of sheep, cattle, horses and chickens to enjoy the rich pastures.

Ancient statues atop Mount Nemrut © Pecold, Shutterstock

Nemrut Daği

Along with Cappadocia and the Sumela Monastery, Nemrut Dağı is one of the best-known sites east of Ankara, and most people will have seen photos of the large stone heads on the top of the mountain. Virtually unknown until after World War II and not even mentioned in the 1960 edition of the Guide Bleu, the site was first excavated by the American School of Oriental Research in Connecticut in 1953. The first outsider to come upon it, however, was a German engineer called Karl Puchstein, who in 1881 stumbled across the statues whilst conducting transport route surveys for the Ottomans. Since the building of an approach road in the 1960s the site has been regularly visited and now, with the upsurge in visitors to Turkey, the droves of people heading up the mountain in organised minibus tours have reached the proportions of a pilgrimage.

Nemrut Dağı has almost no significance historically, being no more than a vast funeral monument to the ruler of a small local dynasty with delusions of grandeur, but for all that – or because of that – it is astonishing, unlike anything else in the world. This kingdom, extending from Adıyaman to Gaziantep, was called Commagene, and was established in the 1st century bc by a local ruler called Mithradates. The Seleucid dynasty in Syria to the south was disintegrating and the Commagene rulers managed to rule independently until ad72 when the Emperor Vespasian incorporated it into the Roman province of Syria. Cicero, Governor of the Province of Cilicia to the south, referred to the Commagenes scathingly in his letters as this ‘petty kingdom’ with its ‘petty princelings’.

19th-century Ottoman houses in Safranbolu © Fran C. Muller, Shutterstock

Safranbolu

Safranbolu represents a pocket of wealth built on the trade of caravans on the silk route between Gerede and the Black Sea in the 17th century. Over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries the prosperous merchants built themselves these beautiful homes, perfectly adapted to the local climate. The richest even built themselves two homes, one in the lower and rain-shadow sheltered Çarşı district for the winter, and another in the higher Bağlar (vineyards) district for the summer.

Safranbolu has what is widely agreed to be the finest collection of beautiful old Ottoman mansions in the country. They date to the 18th and 19th century and are built of timber frames which were then filled in with adobe (mud brick) and then plastered over and usually painted white but with the timbers still showing. Most are two or even three storeys tall and quite square in shape, standing detached in their own gardens. The larger mansions had ten to 12 rooms and often had internal courtyards and separate areas called selamlık, where the men received guests, and the haremlik where the women and children lived. The ceilings were often very beautifully carved and throughout the house there were decorative elements either of carved wood or plaster, according to the wealth of the owner. The Safranbolu houses also often had a revolving cupboard (donme dolaplar) between the selamlık and the haremlik so that the women could pass prepared food for guests without themselves being seen.

The tiny cupboards around the rooms were designed to store the bedding during the day when the rooms doubled as living areas with seating on low benches (sedirs). Today ingenious conversions have managed to make these into tiny en-suite bathrooms, and you can see them properly if you stay in one of the hotels and pensions that many of the larger homes have now become. The household animals used to be kept downstairs in the courtyards overnight, while the living areas for the family were upstairs, often with attractive overhanging window areas supported on carved wooden corbels.

Urfa

From afar the slopes of Mount Ararat look deceptively easy to climb, but in practice the jagged lava fields are very tricky to negotiate, and significant numbers have been killed in the ascent. Long considered impossible to climb by local people, it was first climbed in 1829 by a German, Professor Parrot, on his third attempt, and then by a steady trickle of German, Russian, British and most recently Turkish mountaineers. All ascents were still discounted by both local Kurds and Turkish officials until the 1950s, and even today some villagers do not believe it is possible to ascend the mountain. Political problems dogged the area for most of the 20th century, and before 1982 there were no more than a handful of successful ascents, many of them illicit.

The base of the mountain’s cone covers an area in excess of 2,500km, a fact which helps us to understand why, in summer 2008 when the PKK kidnapped three Germans from Camp 1 at 3,200m and hid with them on the mountain for ten days, the Turkish military had no chance of finding them, or indeed of sealing off the mountain. The risk of kidnap by Kurdish separatists is small, but when times are tense, the Turkish authorities close the mountain to climbers. It was closed for several years in the 1990s, but reopened in 2000. It has generally stayed open ever since, apart from the occasional short closure, such as the six-week closure that followed the kidnap of some German climbers in summer 2008. Whole communities of Kurdish nomads live on the lower slopes of Ararat in the summer months, below 3,200m, either in villages or in tented encampments with their livestock of sheep, cattle, horses and chickens to enjoy the rich pastures.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Eastern Turkey:

Related articles

From crumbling Persian empires to colossal Roman cities, here are some of our favourite ruined civilisations from around the world.

Diana Darke takes a closer look at the ancient temples, Ottoman mansions and remote valleys of Turkey’s little-visited eastern region.

Marble caves, salt lakes and rainbow mountains.