The Arctic is a huge area. There is no clear agreement on its extent, no simple geographical or even political definition of its territory.

Tony Soper, author of The Arctic: the Bradt Guide

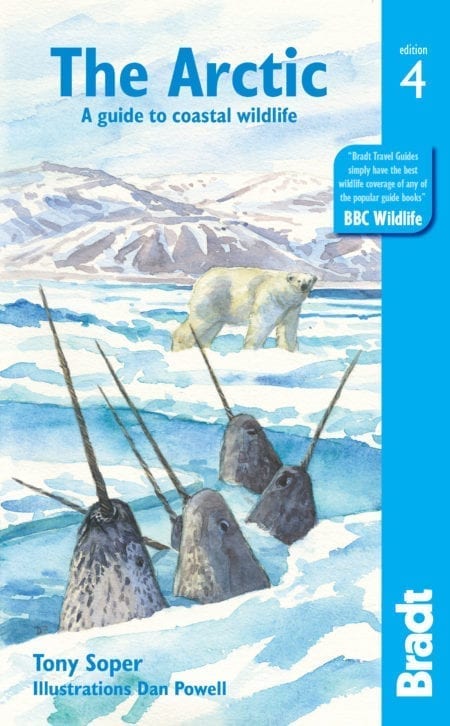

The Arctic has stunning coastal scenery and a wealth of wildlife, from narwhals and belugas to glaciers and tundra, and not to mention polar bears and gyrfalcons. The permanent home to only a handful of hardy creatures, it is an inhospitable place for much of the year. But come summer, the region explodes with life.

Plankton flourishes to support fish, seals and whales, a huge number of shorebirds and waterfowl arrive to take advantage of flourishing insect life. For a few short months there is endless daylight and a parade of wildlife delights. At risk of climate change and industrial exploitation, it needs all the help it can get.

What to see and do in The Arctic

Arctic fox

Circumpolar and restricted to the Arctic, these foxes are most abundant in the coastal regions, although they wander freely over the sea ice. They are often the only indigenous land mammal present in a region, for instance on Svalbard. They are small, much smaller than the red fox of lower latitudes, of which more than half is tail. The dog is heavier than the vixen.

The Arctic fox has a short, blunt head with small furry ears and thick insulating underfur, all in pursuit of effective heat retention; it may survive in temperatures as low as 70ºC. ‘Gloger’s Rule’ says that terrestrial vertebrates tend to be white if they live in the far north, an adaptation to living with snow, and the Arctic fox is a perfect example, along with the polar bear and the ptarmigan. But in summer they are dimorphic, appearing in two forms – greyish-brown or smoky-grey. The smoky form, known as the ‘blue’ fox, is less common in the Canadian Arctic, but represents about half the population in Greenland, Jan Mayen and Iceland.

Rather solitary creatures for much of the year, they nevertheless enjoy a strong pair bond, reuniting at the family den for the breeding season between February and May. The den will be in sandy soil or soft ground, perhaps burrowed into a creek or lake bank, the side of a pingo or a dune ridge. It will have a series of tunnel entrances, and is very often sited alongside a seabird colony, of little auks for example. The vixen may breed in her first year, but more normally in her third, dropping an average of seven pups, but as many as twenty. They are born in the underground den in the late spring after a 51–57 days gestation period. By mid-summer they will be weaned, at a time when the abundance or otherwise of food will have a major impact on success. At this time the dog fox will bring food to the den for the pups to learn to tear apart. They are cared for through the summer until they disperse to forage and fend for themselves. The foxes may not breed at all in a year when food is scarce.

Given fast ice or convenient ice floes to aid its travel the fox, which is perfectly capable of swimming short distances, may cover great areas in search of food. Whereas mainland populations prey mainly on rodents such as voles and lemmings, on the high Arctic islands much of the fox’s food comes from seabird colonies and tideline carrion. Coastal individuals are heavily dependent on fish, eggs, and young seabirds and the scavenging potential offered by polar bear leftovers. In fact they are opportunists, eating anything they can get hold of. Along the coast of east Greenland, foxes will establish themselves close to the cliffs where barnacle geese are nesting, in order to snatch the goslings as they leap off the nest ledges and while they are negotiating the scree boulders on their way to the grazing grounds of the tundra. In this activity they are greatly helped by the way the adult geese honk a distinctive call at the crucial moment of the jump.

Rising temperatures are encouraging northward expansion of the temperate red fox; Arctic foxes are in decline.

Arctic hare

Arctic hares are highly adapted to a life on the tundra. They have the short ears typical of all Arctic animals, making them less susceptible to cold. They also enjoy a thick fur coat. Somewhat rabbitlike in demeanour (also known as jackrabbits) they are found on the barren grounds north of the treeline, from Greenland to northern Alaska across the top of Canada. Their pelage is grey-brown in summer, moulting to snow-white in winter. But, astonishingly, those of the Baffin area stay winter-white all year round, making them highly visible and, surely, even more attractive to predators like Arctic foxes. They are active and sociable creatures, moderately indifferent to contact with people. You might see one hop like a kangaroo, forepaws held in the begging position.

Powerful sharp claws and projecting teeth help them to dig for food under the snow in hard conditions. They enjoy the bark and leaves of dwarf willow. The Inuit take them unenthusiastically for the pot but use the skins for clothing.

Auks

Auks are black-and-white sea-going birds which come ashore only to breed on cliffs and cliffslopes. At their breeding places they congregate in noisy clusters, standing upright in penguin fashion. Hunting prey they use their wings to ‘fly’ underwater in hot pursuit of small fish and plankton. Their wings are short and paddle-like, and their flight in air – though they are somewhat reluctant to fly at all – is fast, furious and direct.

The most abundant of Arctic auks, the little auk has strongholds in Greenland – well over a million breeding pairs – and Svalbard – well over ten million breeding pairs – and has extended its range even to the northernmost part of Franz Josef Land. Little auks are highly gregarious birds, gathering at sea in great rafts inshore, taking off for mass aerobatics, almost darkening the sky, before coming ashore to their nests.

The Arctic is also home to huge colonies of guillemots, including common guillemot and Brünnich’s guillemot, and the less sociable black guillemot, which often hunts alone but may join with others to form line-abreast on the water and herd fish.

Brown bear

Once much more widely distributed, the grizzly has now retreated to the relatively few remaining wildernesses, but there is a fair chance of seeing one on the coastal Arctic tundra. Though closely related to the polar bear, it is a land-based animal. In colour, it is a mix of chocolate-brown, tan and sandy-buff. Unlike the polar bear, it is decidedly territorial, and aggressive in defence of its resident females.

As a tundra-dweller, the brown bear’s diet contains a high proportion of plant food, including berries and roots. But it will hunt whatever mammals present themselves, from caribou/reindeer to lemmings and voles. Although they have been known to kill a seal, they are more likely to scavenge the sea ice, taking advantage of the leftovers from a polar bear kill.

The Sami people of Siberia regard them as sacred, treating them as messengers from the gods, worthy of proper respect while still a welcome food source. Like its marine cousin, the grizzly is dangerous, as it is more inclined to attack than retreat.

Gulls

Gulls are sturdy and sociable birds with powerful bills, webbed feet, long and pointed bowshaped wings and fairly short, square tails. The sexes are similar in plumage, immatures tending to a mottled grey-brown, adults becoming more white, grey and black after several years. They nest noisily and colonially, sometimes in large numbers, often in close proximity to a convenient food source. Scavengers by trade, they take anything from seashore invertebrates to carrion to the eggs and chicks of other birds, including those of their own species.

Polar bear

Circumpolar and a decidedly marine mammal, the polar bear’s whole life is associated with the pack ice. Normally living within 200 miles of the shore, polar bears travel as far north as the pole. From east Greenland to Novaya Zemlya there may be 5,000 individuals, 2,000 of them in Svalbard waters. Satellite tracking has shown that polar bears range widely between southern Svalbard and Novaya Zemlya.

The polar bear is a huge animal, especially threatening when it stands up on its hind legs. Males may stand 2.6m tall and weigh over 400kg, females rather less. A curiously small triangular head sits on top of a long neck and a massive body encased in a thick layer of blubber. It has a roman nose, small eyes and short, round, furry ears. Its long legs are covered with dense fur and its large feet are covered with fine hair even to the toes; the soles are densely hairy. It has yellowish-white fur throughout the year in aid of cryptic colouration – camouflage. The long guard hairs form a watertight outer coat over a soft and fluffy undercoat which traps a layer of air against the skin; this allows it to swim well without getting wet to the skin. Once out of the water a quick shake leaves the outer coat almost dry. The guard hairs are air-filled and exceptionally strong. If you are lucky enough to find a tuft of white hairs on the shore, try pulling one apart. If it breaks it belongs to a reindeer!

‘…as the master walked along the ship, he heard a beast snuffe with his nose, and looking overboard he saw a great beare hard by the ship, wherewith he cryed out, a beare, a beare; and with that all our men came up from under hatches, and saw a great beare hard by our boat, seeking to get into it, but we giving a great shout, shee was afrayd and swam away, but presently came backe againe, and went behind a great peece of ice, whereunto we had made our shippe fast, and climbing upon it, and boldly came towards our shippe to climb up the bow, but we had placed the sail on deck as a screen and lay with foure peeces at the capstan and shotte her into the body, and with that, shee ranne away; but it snowed so fast that we could not see whither shee went, but we guest that she lay behind a high hummock of ice.’

Gerrit de Veer (9 August 1596) in The three voyages of William Barents to the Arctic Regions, Hakluyt Soc, 1876

The polar bear is buoyant in the water, with its head held high. It is a strong swimmer, with seemingly endless stamina. One individual was GPS-tracked swimming continuously for 232 hours, covering a distance of 687km in water varying from 2 to 6˚C. The bear’s main prey is seal, including bearded and harp, but especially ringed seals. It has a keen sense of smell and can detect seal pups even beneath the snow.

Polar bears are solitary by nature, living perhaps the loneliest life on the planet, but there may be a gathering of numbers to take advantage of an abundance of food. Of course there is also interaction at the time of breeding – the only time both sexes meet. They court in the spring, but after copulation in early summer the male takes no further part in the process. Implantation is delayed, and the female takes to a den excavated in the snow in late October. One, sometimes two, helplessly weak cubs are born in the den in late December. At this time they are blind and almost naked, but their diet of rich milk – 30% butterfat – means that by the time the mother breaks free in April, the cubs have increased from a birth weight of 680g (1½lb) to a healthy 11kg (25lb). At this time, conveniently, ringed seals have just given birth and are at their most abundant and their most vulnerable.

The mother will take care of the cub or cubs, teaching them their predatory trade for a good two years before she abandons them to make their own way over the ice and the polar seas. Starvation is the commonest cause of mortality in the first couple of years after they are abandoned. The females breed only once every two years.

Summer is the lean time for polar bears. Deprived of the fast ice with its breeding population of seals, they come ashore to snooze the time away on tundra meadows, eating eider ducks and chicks, grazing the sparse vegetation and searching for ripe berries. At this time they are hungry and dangerous. They need to be taken seriously.

Polar bears have been much persecuted in the past, especially by the Norwegians with the devilish ‘self-kill’ device of a gun set within a cage, offering a choice morsel to the inquisitive bear. In taking the meat, it releases the trigger. From the 1950s, they faced safari hunters. Since 1973, they have enjoyed circumpolar protection, at least on paper, allowing only native hunters a quota. Now they face global warming.

Raptors

Raptors – birds of prey – are diurnal carnivores, hunting live prey, though they are not above taking carrion. Typically they have strong feet with which they grab and kill, while powerful hooked bills are used for tearing prey. The males are usually smaller than females. They are superb fliers.The white-tailed sea-eagle, for instance, appears massive in flight, with broad, rectangular, deeply fingered wings and a white wedge-shaped tail. It is fairly widespread along the coasts of the Russian Arctic, Scandinavia (but not Svalbard), Iceland and southwest Greenland (as well as the Middle East and Eurasia).

The gyrfalcon, meanwhile, the largest and most northerly of falcons, is a truly Arctic species. A coastal and inshore bird, it holds vast territories. Smaller than the gyrfalcon, the peregrine does not penetrate so far north and has totally different hunting habits. A stocky falcon with a short tail and a prominent ‘moustache’, it is compact and powerful. In flight its wings are broadly based but sharply tapered towards the tips. The female is significantly larger than the male. It is widely distributed from the tropics to the Arctic, where it is circumpolar, with strongholds in Novaya Zemlya, Franz Josef Land and the Siberian Arctic.

Reindeer

The most northerly of all deer, the reindeer’s range is circumpolar on the tundra. Sub-species of the reindeer range from Arctic Canada – the Peary caribou – by way of introduced animals in southern Greenland to Svalbard, where the smaller version R. tarandus platyrhynchus is closely related to the Siberian and Canadian reindeer and is presumed to have arrived via the winter ice from Severnaya Zemlya and Franz Josef Land. They are not related to the domesticated reindeer of Scandinavia.

Reindeer are all small animals, but the buck of this Arctic sub-species reaches only to about a metre at the shoulder. They range widely over the tundra and islands, are slow-moving and are relatively easy to approach. The population in Svalbard was in danger of extinction from hunting until it was given legal protection by the Norwegians in 1925; it is now moderately abundant. They are the only deer in which both sexes wear antlers, those of the males being particularly impressive on such a small body; those of the females are less generous, being little more than forked spikes. Adaptation for the Arctic includes a thick coat and a hairy muzzle. The ears and tail are short, reducing loss of body heat. They have broad and deeply cleft hooves which splay out for support on snow.

In winter reindeer forage for lichens; in summer they graze the abundant vegetation of sedges and grasses, perhaps taking a few birds and bird eggs, even lemmings if they are available. During the summer months they patronise the coast to feed almost continuously in order to build up a layer of fat which will see them through the hard times of winter.

The rut takes place in September or October, when a dominant male holds a herd against intruders until towards the end when he is exhausted and lesser males have their wicked way. Males shed their antlers after the rut and grow replacements in the following spring. Females keep them through the winter, shedding after giving birth to the single calf in May or June. Lactation lasts three months, during which time mortality of the calves is high on account of predation by bears and foxes. In Greenland, sea eagles probably concentrate more on afterbirths and the opportunities arising from sick or injured calves than healthy young.

The Arctic reindeer tend to be more gregarious than those of lower latitudes, and they make impressive long-distance seasonal migrations.

Seals

Seals are well adapted to aquatic life in polar regions, cushioned and insulated from the cold air as effectively as they are from cold water with a thick coat of blubber and dense pelage. There are two main divisions – or Superfamilies – in the Pinnipeds. First the Otariidae which includes fur seals, sea lions and walruses. In the Arctic, the main representative of these ‘eared’ seals is the walrus (although the northern sea lion has a stronghold in the Bering Sea). The other major grouping is the Phocidae, the ‘true’ seals which have no protruding external ear, cannot run or raise themselves on fore-flippers, cannot swivel their hind flippers and must clumsily haul or hump themselves on land in caterpillar fashion. These are well represented in the Arctic.

Seals have torpedo-shaped bodies superbly designed for fast underwater travel. Their nostrils are closed and sealed by muscular contraction as they enter the water and they exhale before diving to reduce the amount of air in their lungs, deriving the necessary oxygen from their well-supplied blood systems. Their heart rate reduces and slows and their metabolism is reduced. On surfacing it is several minutes before their heart rate returns to its usual surface beat.

Breeding must occur ashore, but they are comfortably able to pup on the fast ice. Males and pregnant females gather annually at the breeding place, where copulation takes place soon after the previous year’s pups are fully grown. Implantation is delayed for three months so that although the gestation period is nine months the annual cycle is maintained.

Polar bears and killer whales are their natural enemies, but seals have also suffered greatly from the depredations of human sealers.

Skuas

The name ‘skua’ comes from the Faroese Old Norse skúgver, presumably a rendering of their chase-call in flight. Known to North Americans as jaegers, skuas are large, gull-like seabirds with dark plumage and markedly angled wings. They have conspicuous white patches at the base of the primaries. Superficially like immature gulls, they are heavier, more robust and menacing in mien, as befits a bird of prey. Theirs is a piratical nature and they have hawk-like beaks to serve it. They are kleptoparasites – carnivorous buccaneers – chasing other birds, mostly gulls and terns, in the air and forcing them to disgorge their catch. True seabirds, they come ashore only to breed.

Whales

Whales, dolphins and porpoises are members of the order Cetacea. They are totally adapted to a life at sea but, as air-breathing mammals, they must surface to breathe. Modifications to the standard mammal design involve a hairless fishshape encased in a thick layer of insulating blubber, the nose on top of the head, forefeet becoming paddles, effective loss of hind feet and the tail becoming a horizontal fluke. Supported by water, they are free to grow to a great size and weight. They are divided into two broad suborders: the Odontoceti (toothed whales with a single blowhole) and the Mysticeti (whalebone or baleen whales with a double blowhole).

In diving, the blowholes are firmly closed and the heart rate is slowed down. Whales are tolerant of a high concentration of carbon dioxide in the blood with which they are plentifully supplied; the result is that they are able to hold their breath for periods that would drown land animals. The breathing passages are separated from the gullet so that they are able to feed underwater without choking.

Working in murky water and at great depths, toothed whales find their prey by echo-location, using ultrasonic pulses which are inaudible to human ears. They also communicate within their group with trills, whistles, grunts and groans, which are perfectly audible above water.

Baleen whales have a profoundly different method of feeding. In relatively shallow water, they plough through the concentrations of plankton (possibly finding them by taste), gulping great quantities of water, expelling it through filter-plates of whalebone by contracting the ventral grooves of the throat and pressing the large tongue against the roof of the mouth, then swallowing the catch of uncountable numbers of small shrimps and larval fish. Not needing the agility and manoeuvrability of the hunting whales, they enjoy the advantages of greater size. The blue whale is the largest animal ever to live on earth – 30m long and weighing 150 tonnes.

The three truly Arctic whales – bowhead, narwhal and beluga – do not have dorsal fins, an adaptation that fits them for working under ice (and of course they are well supplied with heat-retaining blubber). But it is possible to see several other species of whale in Arctic waters, especially in the summer. Fin, humpback, minke and pilot whales have been recorded commonly, and even the blue whale is sometimes seen in the coastal waters of the Denmark Strait in summer. There is always the chance of killers.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to The Arctic:

Related articles

It is, quite simply, magical.

Expert author, Tony Soper, uncovers the history of the pioneers of Arctic exploration.