Umbria’s majestic, lush Tiber valley is home to three ancient and fascinating art towns, each dramatically different and each boasting secret underground worlds.

South of Perugia, Old Father Tiber flows below the proud eagle’s eyrie of Todi then swells behind a dam to form the Lago di Corbara and takes a sharp left to border Lazio. This corner of Umbria has a character all of its own, concentrated most densely in Orvieto, where mementos of Etruscans rub elbows with papal nobility, under the shadow of one of Italy’s greatest cathedrals. Amelia, wrapped in walls ancient to the ancients, is the third town here, charming but often forgotten in favour of a more well-trodden path.

All three towns make a fantastic addition to any itinerary covering this gorgeous region of Italy. Here’s what not to miss.

Todi

The town of Todi enjoys a gorgeous setting high over the Tiber, nested in three rings of walls, with a medieval piazza so lovely it has been used as a film set, and a proud escutcheon, a fierce eagle over its device SPQT (Senate and People of Todi).

Its beauty attracted artists, and in the 1990s it made the headlines when Richard S Levine, a professor of architecture at the University of Kentucky, chose it as an example of a sustainable town that has adapted over the centuries – which was good enough for the Italian press to declare it the world’s most liveable town, which brought American tycoons to snatch up villas and castles as holiday retreats, inviting comparisons with the Hamptons on Long Island, where wealthy New Yorkers spend their summer.

Whether hoping to socialise with the American elite or simply relax among some of the most picturesque surroundings this region of Italy has to offer, Todi is unlikely to disappoint.

Soak up the sun in the Piazza de Popolo

There is no better place to get a sense of the atmosphere of an Italian town than in its piazza. Todi’s streets converge on the Piazza del Popolo, the centre of civic life ever since the Etruscans. After its glory days as a medieval comune, it was preserved in aspic, leaving a medieval pageant in grey stone.

The stern Palazzo dei Priori (1293–1337) has square battlements with a chunky tower, while the Palazzo del Popolo (1213), with swallow-tail crenellations, and its adjacent Palazzo del Capitano (1290), are all graced by comparison. These last two, linked by a grand Gothic stairway, make up one of the most remarkable medieval town halls in Italy; these outer stairs emphasise how easy it was for the citizenry to have access to local government.

Learn about town culture in the Museo Pinacoteca di Todi

The Museo Pincacoteca is home to a variety of unexpected oddities that offer a small insight into Todi’s unique history.

The city’s attic museum harbours fond civic memories immortalised in retired eagles (clutching rolled-up tablecloths), archaeological finds, including a bronze pig, 16th-century scenes of charity, among portraits of saints and worthies, a model of the Tempio di Santa Maria della Consolazione from 1570, a fine Coronation of the Virgin by Lo Spagna, and paintings by a 16th-century so-so painter, Ferraù da Faenza, who spent a lot of time in Todi. The town is especially proud of a saddle it made for the ailing and pregnant Anita Garibaldi.

Marvel at the Tempio di Santa Maria

This is the most ambitious attempt in Umbria to create a perfect Renaissance temple, a beautiful essay in pure geometry, isolated on the slope of Todi’s hill. The church was designed by the otherwise unknown Cola da Caprarola but shows the influence of Bramante, who may indeed have helped with the design. Scholars attempting to unravel its origins found only more puzzles: a similar design was discovered in an architectural sketch by Leonardo da Vinci from 1489.

Begun in 1508, but not completed until 99 years later, there was time for every starchitect of the day to stick in his oar, including Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, Peruzzi, Vignola and Sanmicheli. In 1589, a Perugian, Valentino Martelli, designed the drum and dome. But too many cooks did not spoil this broth: the Tempio’s purity of form, harmonious restraint, and careful proportions of the dome and four apses (three polygonal and one semi-circular) emerged as if the work of a single genius.

The interior, in the form of a Greek cross, is white and serene, with good Baroque statues of the Apostles and an altar with a venerated 15th-century fresco of the Madonna della Consolazione.

Don’t miss… Grechetto di Todi

This dry white wine dates back to the Roman Republic and is a favourite among locals and visitors alike. No visit to Todi is complete without a leisurely dinner in one of the town’s restaurants (we recommend the pasta with wild asparagus at Pane e Vino) and a glass (or two) of Grechetto di Todi!

Orvieto

There’s no mistaking Orvieto, a town that owes much of its success to an ancient volcano which created the city’s rupe, its magnificent pedestal of golden tuff – a 322m sheer-cliffed mesa that wouldn’t look out of place in a cowboy film – and enriched the surrounding hills below with the minerals that form part of the alchemy of the eponymous wine.

Orvieto is a solid, bourgeois, medieval town, dotted with palazzi built for Roman and local bigwigs. In 1999, along with Greve in Chianti, Positano and Bra, it founded the Cittàslow movement, dedicated to making small cities a pleasure to live in. Today Orvieto is the movement’s international headquarters and the perfect place to get a glimpse of the enviable Italian way of life.

Visit the town’s candy-striped cathedral

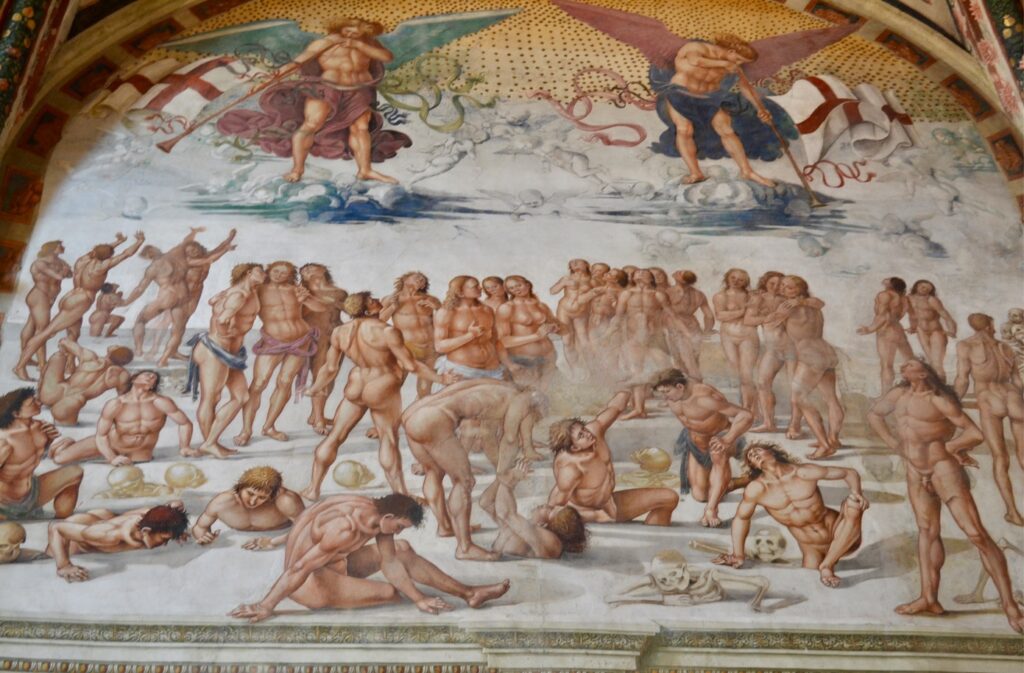

Orveito’s Duomo is visible for miles around, but it is best known for its sumptuous polychrome façade resembling a triptych. Nicknamed the ‘Golden Lily of Cathedrals’, Lorenzo Maitani of Siena’s creation is an architectural and decorative whole, its geometric forms and gables emphasised to make them strong enough to take the lavish detail.

Close up, the richness of the sculptural detail is breathtaking. Some 152 sculptors worked on the cathedral, but it was Maitani himself who contributed the best work – the remarkable design and execution (along with his son Vitale, and Nicolò and Meo Nuti) of the bas reliefs (1320–30) that recount the stories from the Creation to the Last Judgement. This Bible in stone captures their essence with vivid drama and detail and is a must-see sight for any visitor to Orvieto.

Get to grips with archeology at the Museo Etrusco Claudio Faina

In the 19th century the Faina family accumulated a superb archaeological collection, then donated it to the city in 1954 where it is now housed in the Museo Etrusco Claudio Faina. There are terracotta decorations from the Belvedere temple – male figures, a warrior, a horse and the goddess Artemis that show a strong Greek influence.

The Venus of Cannicella, an Archaic Greek statue (6th century BC), was found in Orvieto’s oldest tomb; a giant warrior’s head from the same period came from the Crocifisso del Tufo necropolis, along with three vases by Exekias (550–25BC), the stars of an exceptional collection of Attic ceramics imported by wealthy Etruscans.

A 4th-century BC sarcophagus shows gruesome scenes from the Trojan War, of Achilles sacrificing Trojan prisoners to Patroclos, and Neoptolemos killing Polyxena, Priam’s daughter, on Achilles’ tomb. Also here are ancient coins, Etruscan gold, bronzes, and a sarcophagus still bearing traces of bright paint.

Enjoy a quiet moment at San Domenico

Built in 1233, just after St Dominic’s canonisation, this was the first Dominican church ever built. It originally stretched for 90m; St Thomas Aquinas taught at the former monastery here.

You can still see St Thomas’s chair and the wooden crucifix that spoke to him; and the elaborate, elegant Tomb of Cardinal Guillaume De Braye (1285), a revolutionary work for the time by Arnolfo di Cambio; the Madonna was modelled after a Roman goddess, but the acolytes pushing aside the curtains to reveal the Cardinal’s body are small, tender, and natural. Also seek out the Cappella Petrucci off the presbytery, designed by Sammicheli, with a pretty majolica floor.

Don’t miss… Orveito Undergound

While visitors to the town might be (unsurprisingly) tempted to stay above ground, they would be wrong to do so. Over the past 2,500 years, the residents of the rupe have excavated a shadow city of galleries containing wine cellars, silos, wells, cisterns, ovens, aqueducts, little religious shrines, medieval rubbish pits, dovecotes – more than 1,000 ‘rooms’ in all. Daily tours are available in English and offer a unique insight into Orveito’s more unusual character.

Amelia

The Elder Pliny and Cato claimed that ‘Ameria’ was among the oldest cities in Italy – founded in the 12th century BC. It didn’t take much advantage of its head start, although it was an important Roman municipium by 90BC and gave its name to the Via Armerina, linking Perugia to southern Etruria.

In a beautiful setting on the ridge dividing the valleys of the Tiber and Nera, modern Amelia retains its tranquillity, at least in its centro storico, even if the surroundings are gritty and prosperous.

Stroll through Piazza Vera

Just off Via della Repubblica, Piazza Vera opens up with a war memorial and the church of San Francesco (1287).

Remodelled in the 18th century, it retains a chapel containing six Renaissance tombs of the locally prominenet Geraldini family; Matteo and Elisabeta’s is by Agostino di Duccio, exquisite if worse for wear. The best-known Geraldini, Alessandro (1455–1525), lobbied in the court of Ferdinand and Isabella for Columbus’s voyage, and was rewarded by being appointed Bishop of Santo Domingo, the first in the New World.

Get a glimpse of history at the Duomo di Santa Firmina

Via Duomo ascends steeply towards the cathedral, passing by way of pretty Via Pellegrino Carleni. At the summit, the 9th-century AD Duomo di Santa Firmina hasn’t had much luck; it was destroyed in the 1200s by Frederick II’s army, rebuilt, burned in 1629, rebuilt and then given a brick façade in 1887 after an earthquake.

Despite this, the cathedral preserves a worn column, where Amelia’s patron saint, Firmina, is said to have been bound and tortured to death under Diocletian in 303 AD. In 1986, John Paul II donated the wooden cross in the left transept, a copy of the one that Alessandro Gerladini left in the Cathedral of Santo Domingo.

In the first chapel on the left, the tomb of another Bishop Geraldini (1476), has reliefs attributed to Agostino di Duccio. The cathedral’s venerated 15th-century painting of the Assumption is usually hidden behind a curtain except in May or between 15 and 20 August so be sure to look out for it if you happen to be visiting Amelia during this period.

See the sights in the Piazza Matteotti

The Via Garibaldi leads into Piazza Matteotti, home of Amelia’s delightful Palazzo Comunale. Fragments of Roman Ameria decorate the courtyard and a Madonna with Saints presides in the Sala Consiliare, painted by Piermatteo d’Amelia who, through art history sleuthing, has been identified as the Master of the Gardner Annunciation.

A steep stair descends to the remarkable Roman cisterns beneath capable of holding more than 4,000m³ of water. Built in the 1st century BC, the ten chambers were filled with rainwater; another channel released the waters periodically to keep them fresh. Guided tours are available throughout the week.

Don’t miss… fiche girotti

Strolling around the hilly terrain of Amelia is no laid-back feat. Reward your efforts and boost your energy with one of the town’s decadent fiche girotti (candied figs), made with cocoa and almonds.

Getting to Umbria’s Tiber Valley

Todi is only accessible by bus until the FCU line reopens. Links to Perugia, Terni, Massa, Martana, Orveito and Collevalenza are provided by BusItalia.

Orvieto is on the main Rome-Florence train line and is also well-connected to Todi, Perugia and Terni via BusItalia.

Amelia is on the BusItalia routes from Terni, Orvieto and Orte with links to Orte station which coincide with the trains.

More information

For more information on Umbria and the Tiber Valley, check out Dana Facaros and Michael Pauls’s guide: