From the political history of Stowe House, to the Baroque delights of Blenheim Palace, join us on a tour of England’s best historic houses.

Castle Howard

Situated in the Howardian Hills, Castle Howard still does what it was always designed to do – dominate and impress. What is in effect one building is the focal point of the whole area, having for instance more attached shops than the nearby villages of Terrington, Welburn, Bulmer, Crambe, Whitwell and Coneysthorpe, put together. Built in its entirety by the end of the 19th century, the house and gardens were opened to the public in 1952 and the estate has not looked back since.

The palatial grandeur of the house, inside and out, is instantly familiar to anyone who has seen the filmed version of Evelyn Waugh’s novel Brideshead Revisited, either the wonderful 1981 TV 11-hour adaptation or the 2008 movie. The grounds are big enough to escape the crowds and get lost in. Public rights of way thread through the wider estate, allowing you to get some choice glimpses for free of the house, the majestic 20-column mausoleum, and Palladian splendour of Temple of the Four Winds from a distance.

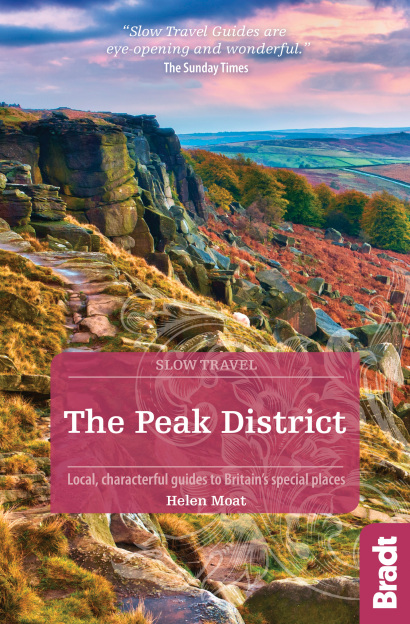

Chatsworth House

What the Peak District lacks in terms of museums is made up for in Chatsworth House. The stately home is a grand and opulent treasure trove of design, art and sculpture.

From porcelain, silver and textiles, to Neoclassical sculptures, furniture, drawings, objets d’art and other curios from around the world, Chatsworth is the V&A of the Midlands.

Kingston Lacy House & Estate

One of Dorset’s grandest houses, Kingston Lacy was the home of the Bankes family from 1665 until 1981, when Ralph Bankes bequeathed the magnificent 8,500-acre estate to the National Trust.

Today it draws a steady flow of visitors for its sumptuous interior, outstanding collections of art and Egyptian artefacts, and serene grounds.

Blenheim Palace

Brushing up against Woodstock, on the outskirts of the Cotswolds, is the huge Blenheim Estate, in the middle of which is Blenheim Palace, the seat of the Duke of Marlborough, aka the Spencer-Churchill family. The house is itself a masterpiece of Baroque, grand in scale and with all the pomp and stature inside and out that you’d expect from a symbol of victory.

In 1874 Sir Winston Churchill was born here, an unexpectedly early arrival while his mother was visiting relations. It’s also where he later proposed to his wife. There is a large, permanent exhibition on his life and work focused around the room in which he was born. Churchill, together with his wife and parents, is buried in the churchyard in the neighbouring village of Bladon, all their gravestones facing towards the Blenheim Estate.

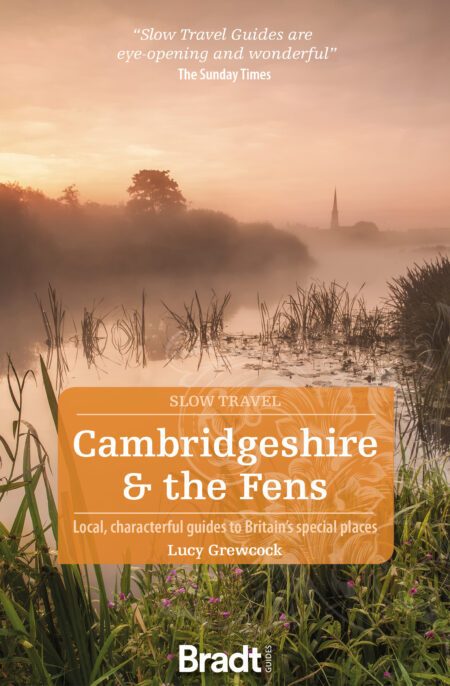

Wimpole Hall

Cambridgeshire’s largest stately home, Wimpole Hall spans 3,000 acres and includes a mansion, formal gardens, rare-breeds farm and sprawling parkland which you can explore on foot or by bike.

There’s a vast amount to experience – inside the main house there are sitting rooms, servant quarters and bedrooms galore. Highlights include a library with more than 6,000 books, and a dramatic drawing room that welcomed Queen Victoria in 1843. Don’t forget to look up at the ceilings – they’re incredibly ornate.

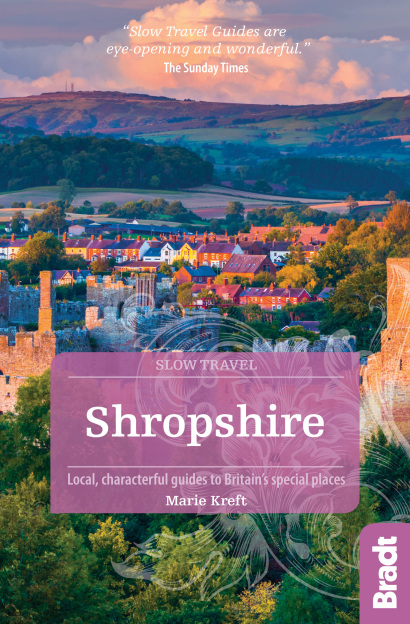

Stokesay Castle

‘Castle’ is a misnomer here since Stokesay, in south Shropshire, is actually a fortified medieval manor house, albeit the best preserved and probably most magnificent example of its kind of England, having never been remodelled – only conserved – by later generations.

It’s largely unfurnished and small in scale so you won’t need hours to view it, but the castle has the power to capture imaginations and its setting is stunning. Stokesay village is less than a mile south of Craven Arms in the valley of the River Onny and cradled by wooded slopes.

Blickling Hall

A couple of miles north of Aylsham, north Norfolk, Blickling Hall has been in the care of the National Trust since 1940. Anne Boleyn may well have been born here, although there seems to be some uncertainty, but the building that you see standing today dates from after her time, the 1620s, and is a superb example of Jacobean architecture.

The miles of footpaths that run through the estate are open and available to be enjoyed for free.

Ickworth House

Amid sugar beet fields a few miles outside Bury in the village of Horringer, Suffolk, Ickworth House is an extraordinary rotunda of a house that is now in the ownership of the National Trust.

It was built at the beginning of the 19th century by the fourth Earl of Bristol and Bishop of Derry as a storehouse for his art collection and estranged wife and family; but some of the intended works of art never arrived because they were taken by Napoleon. Notwithstanding this setback, a collection was amassed that includes Gainsborough, Titian and Hogarth paintings as well as a vast array of Regency furniture.

The exhibition in the basement beneath the rotunda depicts 1930s life in domestic service at Ickworth. The surrounding park, open throughout the year, was landscaped by Capability Brown between 1769 and 1776, although the basic design goes back to around 1700 when the first Earl of Bristol carved out the landscape to his own requirement after the original Ickworth Hall was demolished in 1701.

A herd of deer was introduced in 1706. Also seek out the Italian-style garden with its terrace walk created in 1821, the walled kitchen garden and the Victorian stumpery that contains a large fern collection and stones from the Devil’s Causeway in Northern Ireland.

Seaton Delaval Hall

Seaton Delaval Hall has become one of Northumberland’s most visited historic properties, celebrated for its formal gardens and exterior by Sir John Vanbrugh (the most famous country house architect in England during the early 1700s), who died a few years before the mansion – one of his greatest – was completed in 1730.

A fire destroyed the interior of the central block in 1822 (the heat was so intense that the roof leading was said to have ‘poured down like water’) and the great hall and saloon remain gutted, but you gain a strong sense of how grand and lavish the entrance must have been before the disaster.

Stowe House

Stowe, the house, gardens and estate, all 250 acres of it, is about power; what it looks like, what you should do with it and who should have it. It is also, paradoxically, a symbol of dissent. Much of this is down to Sir Richard Temple (1675–1749), later Viscount Cobham, who fell out with Sir Robert Walpole, the prime minister, and was dismissed from his government.

Visit the impressive house to discover how Cobham used Stowe as a base from which to mentor younger politicians whom he hoped would uphold the Whig vision of liberty which Walpole had (in the view of Cobham and other dissidents) abandoned. But if your interests lie less in political history and more in landscape gardening, don’t miss the Grecian Valley – an early example of the more informal style of landscape for which Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown (1716–83) became famous. The landscape garden and park Stowe are open, and visits must be booked in advance.

Athelhampton Hall

Thomas Hardy was a frequent visitor to this beautiful manor house in Dorset dating from the 15th century, and he referred to it in his writings as ‘Athelhall’. Today, the owners live in the Edwardian extension and open the oldest parts of the house to the public. A carved stone monkey wearing a chain sits above the front door, and he makes appearances throughout the house, including in its stainedglass windows. He is also said to make ghostly appearances.

The story goes that he lived as a pet in the hall in the 15th century but was accidentally imprisoned in a secret passage, starved to death and has haunted the house ever since. Don’t miss the delightful Grade I-listed gardens surrounding the house, which visitors are free to wander. Largely laid down in the late 19th century, they feature perfect topiary pyramids and colourful herbaceous borders. Highlights include a supremely photogenic 15th-century dovecote and a 19th-century toll house.

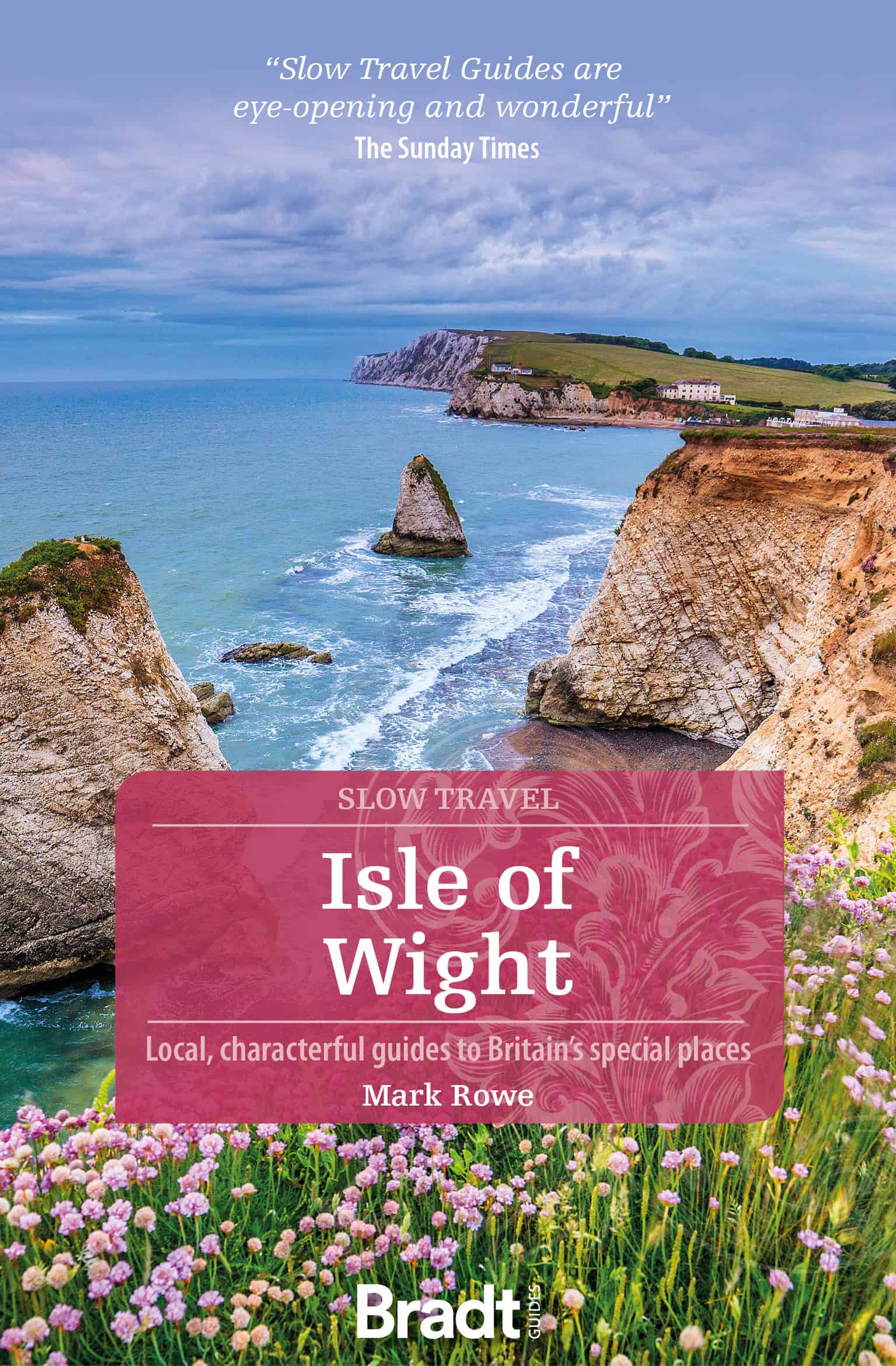

Appuldurcombe House

Along the westerly edges of the large, missable, village of Wroxall is the Grade I-listed Appuldurcombe House, widely recognised in its heyday as a masterpiece of 18th-century English Baroque architecture. Sadly, the same could not be said of it today. Despite being regarded for 150 years as the finest house on the Isle of Wight, it had fallen into disrepair by World War II.

Today’s visitor encounters a slightly surreal spectacle: a stately home version of the ruins of Fountains Abbey or Whitby Abbey, set in 11 acres of pleasingly landscaped Grade II-listed grounds originally shaped by Capability Brown, with mature yew and oak trees and rolling lawns hemmed in by wrought-iron fences. The house was built as the seat of the Worsley family, who were a classic example of a gentry family making a fortune out of royal favour in Georgian times. In reality, the rot set in even as the house was being built, for its ruinous cost stretched the family to the limit and they eventually ran out of cash to pay for the building to be fully completed.

More information

For more information, check out our guides: