There’s nothing like a spot of crafting on a rainy day. Whether you’re grabbing your crochet hooks, sharpening your colouring pencils or threading your embroidery needles, creating something from scratch brings with it an undeniable sense of satisfaction.

But across the globe, traditional craft also plays an important role in a country’s culture and economy. Below are a selection of our some of favourite handicrafts around the world: from delicate needlework to intricate woodcarving. The perfect inspiration for your next project!

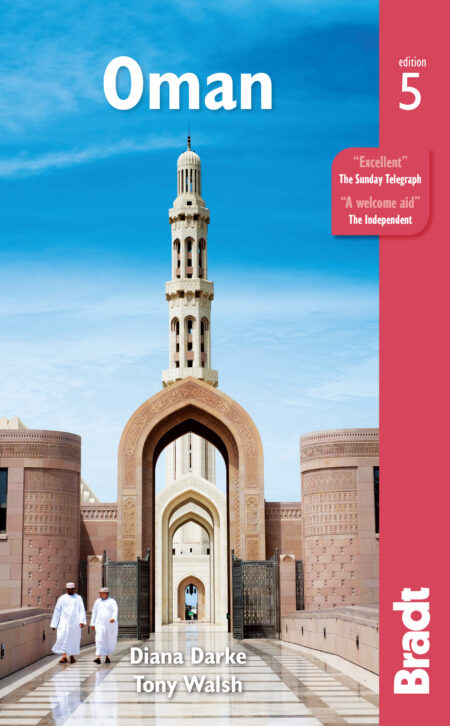

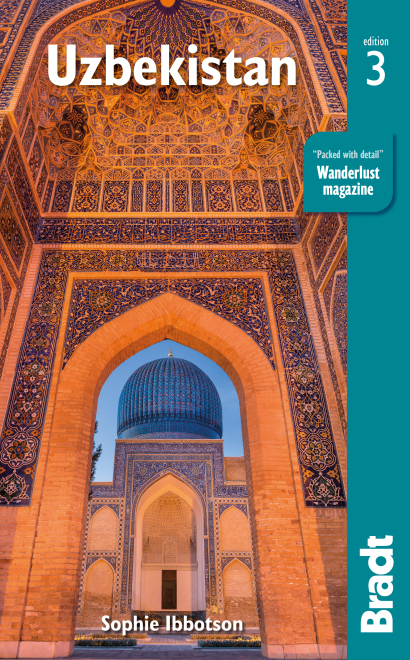

Suzanis, Uzbekistan

The suzani is an Uzbek embroidery. Though suzanis can be sewn on to a single piece of fabric (usually cotton), it is not uncommon for several pieces to be stitched together into an elaborate patchwork. The three main stitches used in embroidering suzanis are chain (yurma), cross (iroqi) and satin (bosma) stitches. The most popular motifs are flowers, leaves and fruits, though the designs often also take on symbolic properties: suns represent life, pomegranates indicate fertility and peppers give protection from the evil eye.

The earliest suzanis seen today, either in shops or in museums, date from the 18th and 19th centuries. Then, as now, they were made by young women for inclusion in their wedding dowries. Suzanis for use as bedspreads, wall hangings and throws were therefore particularly common. Today, suzanis can be bought throughout the country: Bukhara is the best place to find ancient ones, while in Khiva you can pay a visit to the Suzani Workshop.

Mandoos, Oman

These are Omani chests that have been traditionally used to store valuables. It is said that this stemmed from a Portuguese tradition that Oman inherited when it was invaded in the 16th century. Today, mandoos can be bought in a variety of sizes (down to jewellery-box dimensions) and are usually made from either walnut or rosewood.

On the surface they are inlaid with brass, gold or silver, in Islamic and geometric designs, and sometimes decorated with precious stones. You will spot them all as decorative furnishing all over Oman, in hotels, official buildings, offices and private homes. They are sometimes referred to as bridal chests.

Batik, Sri Lanka

The making of batik is a Sri Lankan village craft that has benefited from foreign demand. Bolts of cloth are put through several stages of waxing and dyeing in village workshops. Designs done by untutored but talented village artists result in bright wall hangings, dress and shirt lengths, and sarongs.

Batik is popular for souvenirs because of its exotic, colourful patterns and light weight, which makes it easy to pack. One place to purchase them is the popular JEZ LOOK BATIK in Matara, Sri Lanka, which Jezima Mohamed has been running for almost 50 years.

Kente cloth, Ghana

Of all the crafts practised in West Africa, few are more readily identifiable with a particular country than kente cloth with Ghana. Strongly associated with the Ashanti, modern kente is characterised by intricately woven and richly colourful geometric designs, generally dominated by bold shades of yellow, green, blue, orange and red. However, in its earliest form, before the introduction of exotic fabrics and dyes through trade with the European castles of the coast, kente cloth was somewhat less kaleidoscopic, since white and navy blue were the only available dyes.

According to Ashanti tradition, kente design originated at Bonwire, the small village close to Kumasi that still serves as one of the main centres of kente production in south-central Ghana. Five kente stools were proclaimed by the first king of Kumasi, of which only Bonwire and Adanwomase remain active. The Ewe people of Volta Region, the country’s other important centre of kente production, maintain that they were the first kente weavers, and that their techniques were adopted in Ashanti after some Ewe weavers were captured as slaves. While the Ewe claim has a certain ring of truth, the reality is that most people now associate kente cloth with Ashanti, where the skills of the finest weavers are reserved for the use of royalty to this day.

Chiprovtsi carpets, Bulgaria

The tradition of carpet-making continues in Bulgaria’s northwest village of Chiprovtsi (and Kotel in the eastern Balkan Mountains). The rugs are woven on vertical handlooms, by the women of the village, who have learned the traditional motifs and patterns from their mothers and grandmothers before them.

Men produce and process the wool. The weavers observe certain beliefs and practices, such as praying and asking for success before starting a new carpet, and they sing and recount stories as they work.

Pottery, Socotra

Traditional Socotri pottery has been made and used on Socotra for millennia, and archaeologists have found pottery similar to that in use today in some of the earliest ruins on the island. It is back-breaking work that is traditionally done only by women; they have to walk several hours just to find a suitable area to get clay and temper, and bring this back to the village to begin making the pottery. The type of temper added to the clay and the methods used in making the pots differ between each region on the island.

Typically, the women either make pots for storage or heating and drinking milk and food, or incense burners. However, today you can also purchase model dragon’s blood trees, Egyptian vultures and even camels. Pottery is normally decorated with designs made using shells before it is fired in a bonfire. It is then sometimes further decorated using either the juice of crushed plant leaves or dragon’s blood resin, which is applied directly to the pot as it comes out of the bonfire.

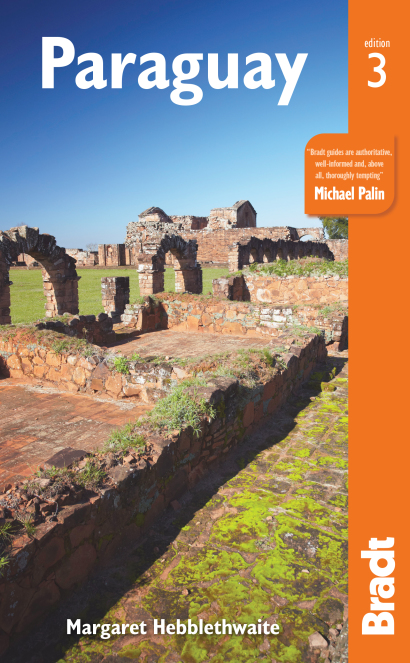

Ñandutí lace, Paraguay

Paraguay is notable for its craftwork. Most famous are its traditional forms of lace, painstakingly done by hand. One of these kinds of lace is called ñandutí, which is the Guaraní word for a spider’s web: this is usually circular in shape, and then the circles are sewn together to make a large cloth. This lace is traditionally made in Itauguá, where there are several ñandutí shops.

The traditional ñandutí is white, and the most delicate examples of this are exquisite. But while foreign visitors tend to like the whites and natural colours, Paraguayans like bright hues, so ñandutí has been developed into multicoloured tablemats and decorations. Particularly beautiful are the long, elaborate dresses made from ñandutí, although they are expensive because they take so long to make. Because the ñandutí is starched, it hangs with a good weight, and makes a superb skirt for folk dancing, with richly subtle colour variations as well as a good swing.

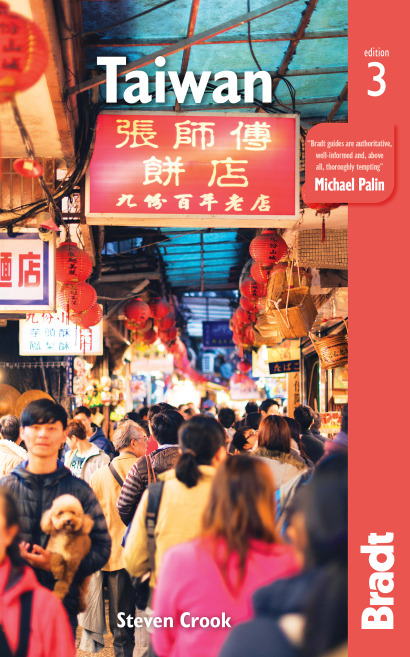

Woodcarving, Taiwan

Sanyi is Taiwan’s foremost woodcarving centre. The woodcarving industry began here during the early part of the Japanese colonial period when the local camphor forests were heavily logged. Roots and stumps were plentiful and carvings made by local artisans were popular with Taiwanese and Japanese Buddhists. Americans were important customers after World War II: Catholics commissioned sculptures of the Virgin Mary while soldiers based in Taiwan picked up souvenirs. Each summer there are exhibitions and competitions.

Over 100 shops sell woodcarvings in the town, and they range from stores packed with mass-produced souvenirs to exclusive galleries, and there’s also the Wood Sculpture Museum, which has galleries on four floors and is permeated by woody aromas. Among the hundreds of religious, practical, decorative and abstract carvings are exquisite prize-winning works by local artists. The most interesting sections are those devoted to the history of the art in China, aboriginal woodcarving and temple carving.

Korhogo cloth, Ivory Coast

Whatever social upheavals have befallen Ivorian society, its arts and crafts scene has always remained vital, fecund and significant. The north specialises in Korhogo cloth, which is renowned across Ivory Coast and West Africa as a singular, high-quality artefact. What is special about it is less the way the cloth itself is produced (hand-spun and woven) and more the artistic techniques used to decorate it.

Liquid is extracted from trees and plants and left to ferment until it has attained a bright, black, sticky property. The paint is then applied to the cloth using a stencil. As with other West African creative modes, Korhogo cloth painting is highly figurative, the deceptively basic pictures of animals and villagers standing for significant cultural, political and religious themes. Chickens, for example, represent fertility and refinement while guinea fowl represent inner beauty and moral uprightness.

Ceramics, Italy

‘Faience ware’ was born in Faenza in Emilia-Romagna in the 1470s, with the invention of a new style of majolica. Terracotta would be coated with a solid white glaze using tin oxide, then rapidly, almost impressionistically, laying down coloured pigment decorated with wavy rays and peacock-feather designs in dark blues, oranges and copper greens that stood out boldly when fired. In the following century, the style achieved its peak popularity, when the potters started depicting histories, mythologies and Biblical scenes, making Faenza a household name across Europe.

Today Faenza has regained much of its 16th-century reputation: 500 students are enrolled in its Istituto d’Arte per la Ceramica and experimental laboratory, and some 60 artists run botteghe in Faenza. Seek out the Vignoli sisters; Ivo Sassi; La Vecchia Faenza; and Goffredo Gaeta.

More information

For more information, see our guides: