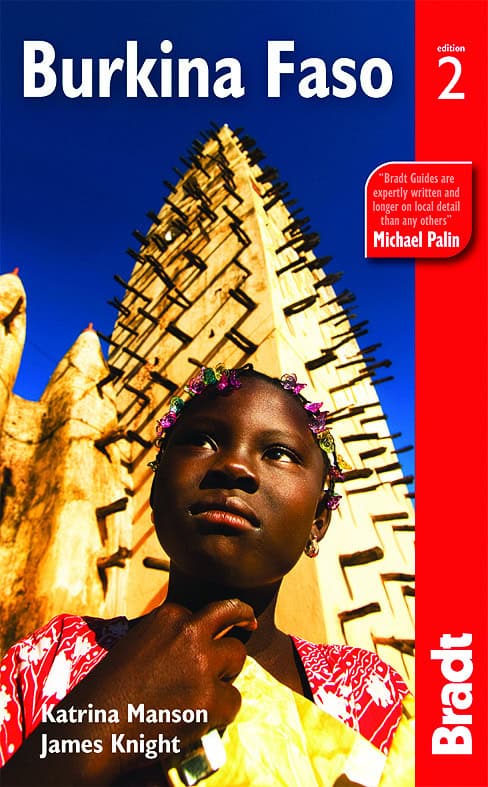

Kassena architecture is undeniably distinctive.

In a country where mud architecture is arresting and varied throughout, the small group of villages east of Po inhabited by the Kassena – one of the sub-groups comprising the Gourounsi along the northern Ghana and Burkina Faso border – is a unique marvel.

The houses are variously circular, square or figure-of-eight-shaped depending on the status of the occupants. They are beautifully decorated with geometric, repeating patterns on the walls.

The best-known and most visited examples of this style are at Tiebele, where a relatively established tourist structure can sometimes feel a little showy or cloying. Still, it’s exactly what the guides say it is – a living museum – and makes a fascinating visit. At Tangassoko, the houses feel more cared for, the atmosphere quieter, and it was much our favourite.

In this article, James Knight and Katrina Manson – authors of our guide to Burkina Faso – give an insight into what the symbols on the houses mean.

Kassena architecture: understanding the symbols

Calabash

The walls of Kassena houses are painted with a repetition of coded geometric signs. The most popular symbol is the calabash – not that you would necessarily recognise it by looking at the paintwork. It is the mainstay of Kassena culture and breaking one is considered a minor catastrophe. It is a jack of all trades: drinking goblet, paint-pot, tombstone, receptacle for sacrifices.

The calabash is entwined in particular with the life, and death, of a woman. A lifelong kitchen companion, it is the only object she is said to take with her after death, and the only object authorised for worship. By tradition, a calabash will be broken on the fourth day after a woman dies, on the path that leads to her parents’ house. All this is represented in the repeated rows of diamond and triangular geometric shapes – fragments of the calabash.

Bats

The Kassena think well of mosquito-eating bats, believing that a house without a bat is an evil one. They endeavour to protect them, and honour a stylised image of bat wings on their walls.

Sparrowhawk wings

Sparrowhawks are feared because they hunt poultry and, the Kassena believe, eat human flesh. Only priests and pallbearers may eat the birds of prey, since only they can avoid serious disease.

Boa constrictor

Look out for these, sculpted in bas-relief onto the sides of houses. They are sacred, thought to hold the spirits of grandmothers, and so never killed, unlike the common fate befalling the viper.

Crosses

Scarification – cutting people’s faces so that healed scars remain in geometric patterns – was much more widespread among the Mossi, mainly for reasons of recognition. But Kassena medicine men believed in scarification to protect against disease. It was practised on children up to the age of three.

Tortoise

This is the sacred totem of the royal family. Should a courtier come across a tortoise in the wild and bring it back to the royal court, he will soon be married, or, if he is already married, he will shortly have a child of the same sex as the tortoise.

Other popular signs

Look out for sun and moon designs, representing the universe; various zig-zags show the footprints of both chickens, used extensively in sacrifi ces, and birds of prey; fi sh skin, drums, bat-wings and poisoned arrows, used in hunting and in battle; lizards, required to ‘christen’ a house by running across it before it can be lived in; the quiver, a reminder that every person is a hunter and warrior; and the pipe and sack, essential accoutrements of old age.

You can find out more about this unique country on our Burkina Faso travel information page.

More information

For more information, check out our guide to Burkina Faso: