In this compelling extract from his book, Minarets in the Mountains, Tharik Hussain explores the hidden Muslim heritage of Zenica’s Sultan Ahmed Madrasa library. Introducing the Effendi, an eccentric and old-fashioned librarian of yesteryear, Hussain offers a fascinating insight into the culture of literary Islam in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

***

We awoke to a miserable, wet Thursday in Zenica. It seems that, during Balkan summers, central Bosnia is the only place it constantly rains.

‘My friend from London loves Bosnia in the summer for that reason. He says the weather is just like London,’ grinned Mevludin Sahinovic.

He was right about the weather: the sky was grey, there was a chill we hadn’t felt since being in Sarajevo, and I could even see London’s famous fog as we walked through the misty town centre.

Mevludin had lived through the Bosnian War, where his brother died fighting for the ‘resistance’ Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH). He now lived in London and we met when he gave a talk at an event to commemorate the Srebrenica genocide, where I was exhibiting some of my photography exploring the Muslim heritage of Europe. Mevludin spent his summers here at home in Zenica, and when I told him about our plans to travel around the Balkans, he insisted I come and see him in his home town.

Knowing the purpose of my trip, he had arranged a visit to a beautiful local Ottoman Islamic school dating from 1720, called the Sultan Ahmed Madrasa. We entered through a set of dark wooden doors into a small, square courtyard, in the centre of which stood an ornate fountain with bronze taps.

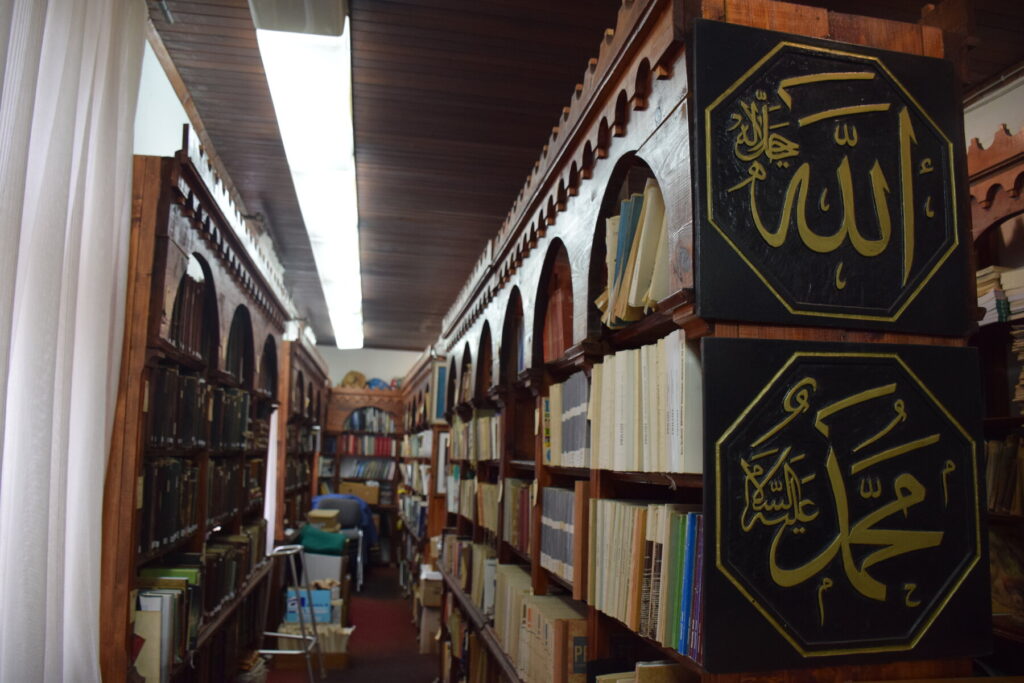

‘Come with me, I want you to meet someone,’ Mevludin said, leading all three of us towards one of the larger rooms overlooking the courtyard. Entering through an open doorway, we were suddenly transported several centuries back in time. Row upon row of ornate wooden bookshelves lay before us, overflowing with books written in a host of languages, from Bosnian through to Persian. Many sat in messy piles, sometimes on the stools and stepladders used for reaching the higher ones. They were waiting to be organised and squeezed in somewhere. Larger books poked out as they lay flat due to a lack of space. Some shelves had ‘Allah’ and ‘Muhammad’ written in gold on large black plaques at the ends, others had black-and-white photos of previous teachers at the school.

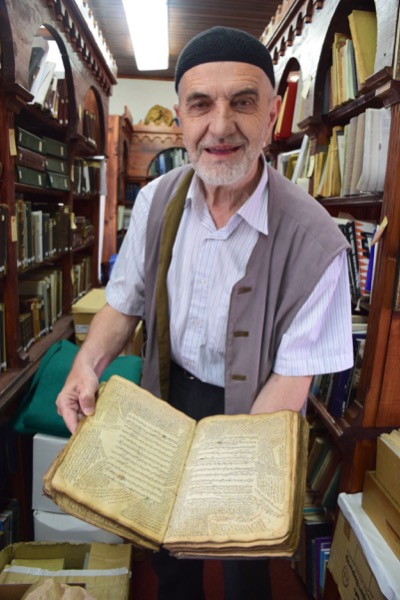

The air was filled with the stench of stale tobacco and old books. It was as if I had walked into a huge secondhand bookshop from another century. Mevludin’s frame filled the aisle as he wandered through it. He was a typically large Bosnian but, untypically, he had a large beard and a shaved head. When he got to the end of the aisle and stepped aside, a huge, old-fashioned librarian’s desk emerged, behind which, cigarette in hand, sat an elderly man wearing a black skullcap, a short-sleeved, stripy shirt and a grey Eastern waistcoat.

‘Salamaleikum, Effendi,’ Mevludin said, greeting the man, who had a short, neatly trimmed white beard. The man returned his greetings and then they began conversing briefly in Bosnian. Mevludin then turned to me, Amani and Anaiya.

‘This is Ibrahim Babic Effendi, the librarian at the Sultan Ahmed Madrasa,’ he said.

I salaamed the man, and so did the girls, before I asked why he was called Effendi. A throwback to the Ottoman days, it was apparently an honorific Turkic title given to Ibrahim because he was one of the lead imams at Zenica’s main mosque. During the Ottoman era, Effendi was often used to refer to ‘educated gentleman’ and was the second most-widely used title after Agha.

‘This is the oldest book in the library,’ translated Mevludin as the Effendi held open an ancient book with yellowing pages and Arabic writing covering every inch. The most legible Arabic was the main words of the book in the centre of each page; emanating from this, in what would have been the margins, were several other paragraphs written in smaller script.

‘These are commentary notes,’ explained Mevludin, who was fluent in Arabic himself, having studied Islam for many years.

The script was in the widely used naskh style of calligraphy, and was apparently a book of religious jurisprudence.

‘It’s a book of fiqh. That’s why there is so much commentary added to the main text.’ Mevludin began examining the text, reading segments of it. ‘It is a combination of Hanafi and Shafi‘i fiqh,’ he concluded.

These were amongst the two most popular schools of traditional Islamic theology, the Hanafi being the most popular in Ottoman territories and the one my parents brought me up with. It was developed by the 8th-century Islamic theologian Imam Abu Hanifa.

‘How old is it?’ I asked.

Mevludin turned to Ibrahim Effendi and the two of them had a brief but animated exchange that made Mevludin’s eyes widen behind his thick-rimmed spectacles.

‘Apparently, it is more than six hundred years old according to some recent experts from Turkey who came and visited the library.’

‘Wow! That’s older than the madrasa. In fact, that’s older than Sarajevo and the Ottomans.’

Mevludin nodded. I could see he was also genuinely astonished.

The Effendi put the book away, before disappearing to grab another.

‘This one is my favourite,’ he said, opening a slightly smaller book with pages that were cleaner than the previous one.

‘This is a Seerah of the Prophet Muhammad sallallahu alayhi wa sallam. It is more than three hundred years old,’ he said, smiling to reveal his nicotine-stained teeth.

A Seerah was a biography of the Prophet. The style of the calligraphy in this book was a more modern naskh font, and it didn’t have a commentary around the main text, which sat two inches in from the edges of the page, all neat and justified. The scribe of this book was not as skilled as the one who had written the fiqh book, as the script was not as artistic. There were markings in red highlighting certain words and, as the Effendi flicked through the pages, we noticed one or two had small annotations on them.

‘I am working on a book that I hope will warn young people,’ he said sitting back down at his desk, which was piled high with papers.

I had asked him about Islam in Bosnia and if he had concerns about young Muslims beginning to lean towards more radical interpretations. He lit a white cigarette and inhaled deeply. His old eyes went from the window into the courtyard where I could see Anaiya posing in front of the fountain. I noted the deep wrinkles under his eyes and around his mouth. He stroked his small, neatly trimmed white beard, as Mevludin and I waited for him to continue.

‘People think Wahhabism arrived here during the war with the mujahideen that came to fight for us. But it was here long before that, when the humanitarian efforts from the east first arrived.’ He flicked his cigarette into a small wooden ashtray, overflowing with used butts.

‘They have taken out the name of Muhammad and the oneness of God from the faith!’ he said, raising his voice and waving his hand angrily. This sent bits of ash all over his desk, which he then carefully swept up.

‘The worst thing is that Saudi theology fails to accommodate or appropriate the Muslim’s heart for taqwa [piety].’

The Effendi stopped abruptly. Mevludin, who was being brilliantly tactful with his whispered translations, fell silent too. We both waited, but he now seemed reluctant to continue, so I tried to cajole him.

‘So why do young people find this attractive?’ I asked. The question snapped him back into life.

‘It offers them a purpose. They are young and this harsh way is attractive to them. This is the fault of the ideologists. Did you know that someone tried to renounce this by writing refutations about the creed and he was not allowed to publish in Saudi so he had to publish his book in Egypt?’

Mevludin and I both shook our heads.

‘We need to go back; we need to go back to Abu Hanifa, and also the great ulema of the past. Young Bosnians need only look at their own heritage to figures like Hasan Kafi Pruščak, who made it clear that “actions” and iman [faith] are not the same thing. “Deeds” are the fruits of iman.’

I had no idea who Pruščak was and couldn’t ask the Effendi either. He was in full flow and becoming more and more animated, jumping from one chain of thought to another.

In the end, the call to prayer from the school’s mosque brought the conversation to a halt. The Effendi explained he needed to lock up to go and perform his salah.

As we headed for the door, I asked him what he made of the rise in Gulf tourism to Bosnia. Was he happy about this?

‘No, I’m not happy about this at all. It is just money chasing,’ he said, locking the library door behind him.

I wanted him to elaborate but it was too late, he was already shaking our hands, and so we thanked him for his time as he hurried off in the direction of the old mosque.

More information

To read more, check out Tharik Hussain’s Minarets in the Mountains: