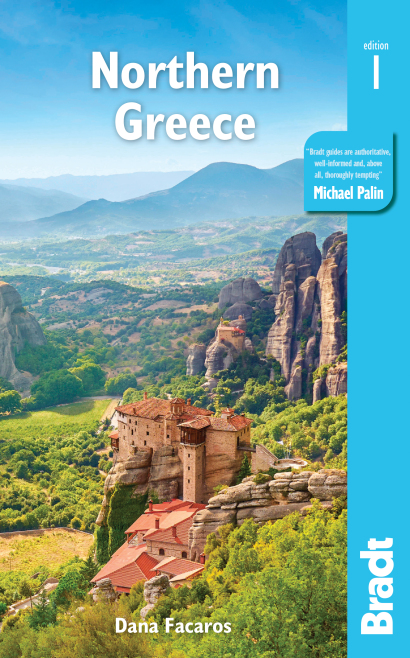

The road from Tríkala northwest to Kalambáka is mesmerisingly boring – until suddenly out of nowhere a forest of sandstone pillars appears, rising straight up from the valley floor. Eroded, iron grey and water scarred, their sometimes stubby, sometimes pointed pinnacles are visible for miles, and from a distance they look as two-dimensional as a cartoon backdrop. More than 800 smooth and windswept rocks, some over 360m high cover 20km2.

Geologists drily call it debris left over from a primeval river delta that the earth pushed up to create a lofty, fault-filled plateau 60 million years ago, but it’s really the mighty Pindus range’s last and greatest conjuring trick, a spectacular geographical non sequitur, before it releases its spell on the landscape and subsides into the dull Thessalian plain.

Even if monks of old had not built in its improbable recesses and on its inaccessible peaks, the area would still be visited for the sheer grandeur of its scenery. Meteora (Μετέωρα) means ‘things hovering in the air’ – as in meteor – as apt a name for the rocks themselves as it is for the stupendous and unforgettable monasteries that crown them. These are the main monsteries to visit. As per usual when visiting Greek monasteries, dress modestly. Women should cover their knees and upper arms; shawls and skirts are available for those who come unprepared. Men should wear long trousers and shirts with sleeves.

Ag Nikólaos Anapavsá

This monastery, now down to its last monk, was built by Dionysios, bishop of Lárissa, in the 16th century over the foundations of an older building. The katholikón (1527) in the centre of every monastery, symbolising the church as the centre of the human cosmos, traditionally faces east, but here it faces north; Meteora’s topography required some rearrangements.

Restored in 1960, its frescoes by Theophánis the Cretan are exquisite, and include one of most the charming scenes in Byzantine art, Adam Naming the Animals. A footpath to Varláam just up the road leads to the base of Varláam’s pinnacle for a look at the 90m-deep Dragon’s Cave.

Roussánou

Dedicated to St Barbara, Roussánou looks as if it grew straight out of its rock pedestal; a frighteningly narrow bridge built in 1868 between two mini peaks replaced an earlier, even scarier approach. Founded in 1545 by Maximos and Joseph of Ioánnina, with art from 1560, it is now a convent with 13 nuns, whose new kitchen inside the entrance nicely highlights an ongoing dilemma for monasticism.

How much of the modern world should this conservative institution embrace? Formica and spiffy new kitchen cupboards look wildly incongruous after the gruesome frescoes in the katholikón (the nun’s habits haven’t changed much, though).

Varláam

The second-largest monastery, now home to seven monks, Varláam is wonderful. Founded in 1517 by Theophánis and Nektários Apsarádas from Ioánnina, it was named after the hermit who originally built on the spot. Its 195 stairs were added in 1932, and its overhanging tower room contains a windlass and rope, next to a tiny lift. The katholikón (1544) has a carved and gilded iconostasis, frescoes by Frángos Katelános, and two charming cupolas, one in the main body of the church and one in the narthex.

Varláam has a fascinating museum in the old refectory, with relics, ecclesiastical treasures and explanations of the monks’ lives, with a great collection of old photos and a documentary filmed in Meteora in 1924 – including a scene of a monk with a mallet banging the semantra, the flat wooden beam all the monasteries have, said to replicate the ‘bell’ Noah used to summon the animals to the Ark.

The Great Meteora

Sprawling over Platýs Líthos (flat rock), this is the big one, and well worth the trek up its 146 steps. It’s the most popular among visitors, who keep its three monks busy. Founded by Ag Athanásos, who flew here on the back of an eagle, it’s officially dedicated to the Transfiguration (Moní Metamórphoseos tou Kyríou).

Its privileges were guaranteed in 1362 by Serbian emperor Symeon Uros, whose son, taking the name of Joásaph, became a monk here and built the first katholikón, at his own expense, in 1387–88; subsequent alterations never needed to be done on the cheap. Joásaph’s original church is now the ierón behind the iconostasis of the 16th-century katholikón – the incorporation of older structures within newer ones, like so many Russian dolls, is common in Byzantine monasteries.

The cross-in-square katholikón under its lofty 12-sided dome was beautifully frescoed by Theophánis and his workshop, completed in 1552. The pictures are exquisite and well preserved: in the narthex, they depict all the gruesome details of the Roman persecution of the Christians, while the saints line up along the walls in the nave. On the pilasters, you can pick out the two founding fathers, Athanásos and Joásaph, each holding a model of the monastery. On the north side of the katholikón, the vaulted refectory (c1557) is now a history and folk art museum. A seashell incense burner is one of its less serious exhibits; others cover the role of the Orthodox church in resisting the Nazis.

The domed kitchen is interesting, as is the library, noted for its 640 fine manuscripts, codices – the oldest date back to ad861 – chrysobulls from various emperors and a rare printed volume of the Greek classics by Aldus of Venice. The cellar has a carpenter’s workshop, with rare old wine barrels. Before leaving, consider the 30-minute path to the restored 14th-century church of the long-gone Monastery of Ypapandí, tucked in a small cavern. A path leads up to the statue of the klepht Thýmios Vlachávas, who organised an uprising against the Ottomans in 1808 but was betrayed and captured by Ali Pasha; chances are you’ll have the views all to yourself.

Ag Triáda

Farther east, on an isolated 400m pillar with ravines on both sides, this 15th-century monastery will look familiar to James Bond Thessaly fans, who will recognise the spectacular backdrop for some of the skulduggery in For Your Eyes Only, when it played the villain’s lair.

The 140-or-so-step approach is mostly through a tunnel, offering some relief for vertigo sufferers. A plinth on the outer wall of the church states it was built in the year 6984 since the creation of the world (1475); the small chapel of St John the Baptist (1682) has gorgeous paintings. Four monks hold the fort.

Ag Stefánou

High on its pinnacle, the easternmost monastery (now a convent with 24 nuns), is separated by a deep gorge from the road; the two rocks are connected by a bridge. It was bombed by the Nazis during the war, who suspected it was sheltering Resistance fighters, then abandoned and rebuilt, so it has a newer look. The fabulous view out over Kalambáka and the plain beyond is alone worth the journey.

Its church of Ag Stefánou (c1350) has a timbered roof, some gold-leaf wood carvings, and wall paintings (c1545) by a local priest, Ioánnis of Stagoi. The katholikón, dedicated to Ag Charálambos (c1798), contains the said saint’s skull, a gift of Vladislav of Wallachia.

A distant dependency of Ag Stefánou, the 18th-century Moní Ypséseos Timíou Stavró (44km west at Dolianá, just north of Kranía (Κρανία) is one of the most unusual churches in Greece. Nicknamed the ‘Acropolis of Aspropotámos’ it is built entirely of stone and punctuated by 13 tall domes. Although the rest of the monastery was burned by the Germans, the church has been lovingly restored by the locals, and stands alone amid the pines, very much like an illustration in a fairy tale.