In Glasgow, Stratford-upon-Avon and Twickenham, you can find the traces of four women who made their mark in a man’s world.

Glasgow: Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh and Catherine Cranston

While the architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) is famous in particular for his work in Glasgow, he could not have gained this reputation without the help of two women. His wife Margaret was a talented designer who worked with him on many projects, while Miss Catherine Cranston was a businesswoman who employed Mackintosh to design her tea rooms, as part of the creation of a unique ‘Glasgow Style’.

Margaret Macdonald (1864–1933) was born in Tipton in the West Midlands, the daughter of a colliery manager and engineer. The family relocated to Glasgow, where she and her younger sister Frances studied design at the Glasgow School of Art. There they met Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Herbert McNair, who worked in similar styles and who later became their husbands.

By 1894, the quartet were showing their work jointly in student exhibitions, becoming known as ‘The Four’, and Margaret and Frances opened a studio in Hope Street in 1896. Charles and Margaret exhibited together at international events, and Margaret collaborated with her husband on projects, including tearoom interiors for Miss Cranston.

Known as Kate, Catherine Cranston (1849–1934) was born into a family of hoteliers from whom she inherited business acumen and a talent for catering. Her brother Stuart was a tea dealer, and his premises allowed space for customers to sample his wares with a sandwich on the side. These ‘tea shops, pure and simple’ (as Stuart called them) provided working-class people with an alternative to pubs, as part of the temperance movement.

Kate saw the potential for something more ambitious. She opened four Glasgow establishments: the Crown Lunch and Tea Rooms in Argyle Street, Miss Cranston’s Lunch and Tea Rooms in Ingram Street, 91–93 Buchanan Street and The Willow in Sauchiehall Street. Kate became a leading figure in the Glasgow hospitality industry for 40 years, the last 21 in partnership with the Mackintoshes.

She remained known as ‘Miss Cranston’ even after she married, relatively late in life. The tea rooms provided a socially acceptable venue for unaccompanied women to meet outside their homes, though men were also catered for; facilities included billiard rooms, smoking rooms, reading and writing rooms. Contemporary journals for the catering trade advised how much might be learned from a tour of Miss Cranston’s establishments – she was a model employer, taking great care for the wellbeing of the young women who worked for her.

It was the opening of Kate Cranston’s third establishment in Buchanan Street that saw the start of her collaboration with the Mackintoshes. Although Charles played only a small part, stencilling a large frieze for the walls, Kate then commissioned him to design new furniture for the Argyle Street premises. Rennie Mackintosh’s work included the innovative high-backed design now known as the ‘Mackintosh Chair’.

In 1900 Miss Cranston commissioned her first complete Mackintosh interior, the Ladies’ Luncheon Room for Ingram Street. Silver and white walls contrasted with dark furniture. Just below the ceiling hung two large gesso panels: The May Queen by Margaret and The Wassail by Charles.

The culmination of the partnership between Miss Cranston and the Mackintoshes came with the opening of the Willow Tea Rooms on Sauchiehall Street in 1903. Kate employed Charles both as architect for the exterior and as the interior designer. Willow was a recurrent theme of the design, from stylised plaster reliefs in the front saloon and stylised willow leaves in a metal screen to the gesso panel Oh ye, all ye that walk in Willowwood by Margaret in the opulent Salon de Luxe. Visitors to Glasgow today can see furniture from the Buchanan Street and Ingram Street premises, along with the originals of The May Queen and the Willowwood gesso panel, in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

The interiors of the Mackintoshes’ home at 78 Southpark Avenue have been reconstructed a few metres from the original site in The Mackintosh House, now part of the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery. Margaret’s gesso panel The Red Rose and the White Rose is displayed above the fireplace in the studio.

For an immersive experience, you can dine in the painstakingly restored interiors of the Willow Tea Rooms, now called Mackintosh at the Willow. The menu has been brought up to date; the fascinating exhibition next door reveals that customers in Miss Cranston’s day could sample sheep’s head and herring in custard. It is well worth booking one of the tours of the building to appreciate the full glory of the designs. The tea rooms, exhibition and tours are run by a charitable trust, which also oversaw the restoration work.

Stratford-upon-Avon: Elisabeth Scott

Elisabeth Scott (1898–1972) was one of the first women to train at the Architectural Association after it began admitting women to its courses in 1917. Architecture perhaps ran in her blood, as her great uncle was George Gilbert Scott and Giles Gilbert Scott was her second cousin.

In the early 20th century, the general expectation was that women in architecture would focus on housing. But in 1928 Scott became one of the first female architects to receive a major UK architectural prize, winning an international competition to design a replacement for the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. Elisabeth submitted her entry under the gender-disguised pseudonym ‘E Scott’.

Her modern Art Deco design was not universally popular. The building’s exterior appearance gained it a nickname, ‘the Jam Factory’. Sir Edward Elgar considered it ‘unspeakably ugly and wrong’ and refused to participate in the opening ceremony. George Bernard Shaw was a supporter, however, considering that the design was the only competition entry to show any theatrical sense.

The theatre, now the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, was redeveloped in the 2000s to meet modern needs, but the outer shell of Scott’s brick-built design remains. Visit the bar area or, better still, book a tour of the building to see the Art Deco box office and other original features.

Twickenham: Henrietta Howard, Countess of Suffolk

Two centuries earlier, Henrietta Howard (1689–1767) made her own mark on the arts. A member of the Hobart family of Blickling Hall in Norfolk, she was an orphan by the age of 12. In 1706 she married Charles Howard, the youngest son of the 5th Earl of Suffolk, but the marriage proved a disaster, as her husband turned out to be abusive.

Henrietta did not despair, raising funds to travel to the Hanoverian court, in the hope of ingratiating herself with the dynasty that would inherit the throne of Great Britain on the death of Queen Anne. Her plan worked. She returned to England when the Elector of Hanover succeeded to the throne in 1714 as George I. She was made Woman of the Bedchamber to Caroline, Princess of Wales and became mistress of the Prince of Wales (later George II) shortly afterwards.

Henrietta received a generous gift of £11,500 of stock, together with jewels, plates and furniture from the prince, which he stipulated must be free from any interference from her estranged husband. As a result, in 1724 Henrietta was able to start building a house, Marble Hill, on the banks of the Thames at Twickenham in the fashionable Palladian style.

Henrietta’s wit and intelligence attracted the attention not only of George II, but also of notable politicians and writers including Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope and John Gay. Through her friendship with Twickenham neighbours Pope and novelist Horace Walpole, Marble Hill became a centre for her cultural, intellectual and political circle. In 1735 Pope wrote that ‘there is a greater court now at Marble-hill than at Kensington’.

Marble Hill House has recently reopened after a major refurbishment project, with displays about Henrietta and her circle.

More information

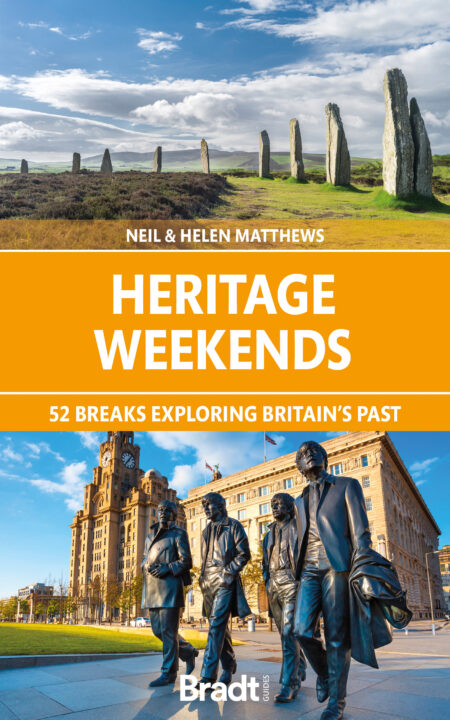

For more information, check out Neil and Helen’s guide: