Written by Doug Goodman

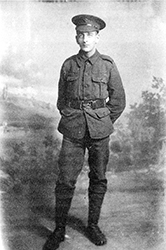

The faded photograph of a solider in uniform among the bundle of 1920s holiday snaps had little significance for me as a child; I remember once being told only that it was my uncle ‘lost in France in the war’. But it was to become very significant indeed.

The faded photograph of a solider in uniform among the bundle of 1920s holiday snaps had little significance for me as a child; I remember once being told only that it was my uncle ‘lost in France in the war’. But it was to become very significant indeed.

In the early hours of Friday 15 September 1916, at a spot known as High Wood near Albert, a whistle gave the signal for infantrymen of the 47th Division to go over the top as Allied forces attempted to capture German trenches along a section of countryside on the Somme.

For Private Alec Reader, the battle was to be the culmination of 13 months’ training as a rifleman and bomb-thrower. It was also to be his last chance for action as his release papers were almost complete; he was being allowed to leave the army because on the day of his enlistment he was only 17 – four months underage.

The Times talked of the 15 September attack as a ‘great day for the cause of civilisation’ and The Telegraph listed several thousand killed and injured. Alec was one of them. His mother received a letter saying that his body had been found in the wood and properly buried.

For years she tried to find out the place of burial, but in 1923 the Imperial War Graves Commission told her that, although the area had been searched and the remains of all soldiers buried in isolated graves had been reverently reburied in cemeteries, the last resting place of Private B A Reader, No 3623 of the 1st/15th Battalion Prince of Wales Civil Service Rifles, remained unidentified.

And that might have remained the case had not his 77 letters home to his family come in to the possession of Doug Goodman, his nephew. His citations and medals were found, press cuttings and official correspondence assembled, photographs acquired and memories jogged. His name was ‘discovered’ on the roll of honour in the chapel of Emanuel School, south London. Military records were examined and visits to the Imperial War Museum and Musée de la Guerre in Paris provided valuable information. Old books on the battles and modern ‘then and now’ publications were obtained, battlefield maps and diaries held were scrutinised, until eventually the missing details fell into place.

It is difficult to imagine the Somme as a battleground now. Neat villages, well-signposted roads, ploughed fields and tidy woods cover one of the earth’s most devastated regions. But hundreds of cemeteries, monuments, memorials and museums attest that something terrible occurred there.

On the edge of High Wood where the last cavalry charge and the first tank attack took place and where more than 8,000 soldiers died, stands a monument to the men of the 47th Division.

On 15 September 2016, 100 years to the hour, on the spot where he died, eight family members remembered Alec. Later that day three generations of the Goodmans placed a wreath on the Thiepval Memorial where Alec’s name is carved in stone, along with over 73,000 other brave men who have no known grave.

Learn more about how to trace relatives from World War I in our guidebook: