In October 2021, our late friend, author and tour guide Geoff Hann headed back to Iraq with a group for the first time in two years. He shared his impressions with us of how this remarkable country has developed over the decades.

* * *

‘I’ve just come back from Iraq.’

‘Iraq?!’

‘Ooh, you wouldn’t get me going there!’

‘Did you take your flak jacket?’

‘Why on earth……?’

Why on earth indeed. These are some of the most common responses I get when I tell people that I’ve just returned to Iraq, or that I’ve been taking other travellers there with my company, Hinterland Travel, for over 50 years now. We’ve taken tours during the Saddam era, after he’d gone (including the infamous post-war tour when US soldiers refused us admission to the blue-domed Martyr’s Memorial, not because of security risks, but because they were sleeping in there), during insurgency and the rise of ISIS and now, post ISIS, as the country and its people recover yet again.

After a two-year hiatus from travelling thanks to Covid, I seized the opportunity to visit Iraq when it reopened earlier last autumn. Of particular interest this trip was the north of the country, in particular Mosul and Hatra. Being a stronghold of insurgency and an ISIS battleground, Mosul had been inaccessible to us until 2018, when we were able to make a short visit – and became the first group to witness the devastation of the north following the ousting of ISIS. I was interested to see what had changed since my last visit.

First impressions

The tour started on an unusual note. A last-minute closure of Baghdad airport because of the Iraqi elections meant the group arrived in the capital the day before the tour officially began. As pretty much everything was closed, it could have been a rather boring day. However, the Baghdad Hotel had a swimming pool in which we enjoyed some cold beers in the 30+ degree heat, while getting to know one another and recovering from our long flights.

Part of the joy of these tours are the interesting – and interested – people who join them. Originally, the majority of those joining the tours would be from the UK and Commonwealth countries, but over the years nationalities have diversified (I remember having an interesting argument at the Kurdistan border with guards who refused entry to a Mexican gentleman on the basis that a country called Mexico did not exist!), but be it their first visit or tenth return, their enthusiasm to learn about the country, its history and its people makes every trip different and rewarding.

We spent the first few days exploring Baghdad – the Royal Tombs, Kadhimiya Mosque and Shrine, the National Museum, the copper souk, the Mustansiriya Madrasa, the Kassite ziggurat at Agarquf and, a particular favourite of mine, Al-Mutanabbi Street, where time stands still as you explore the bookshops and outdoor bookstalls that have long contributed to this street’s reputation as the centre of Baghdad’s cultural and intellectual community.

Then, it was time to head north. Making an early start, we drove first to Samarra to admire the magnificent, ruined 9th-century Abbasid Great Mosque, with its iconic ascending spiral minaret, before heading to Tikrit. Standing on the banks of the River Tigris, this was once the family home of Saddam Hussain and is where he was buried – and owing to a security mix up, I once saw this fabled tomb.

When we visited Tikrit I always asked to see it and my request was always firmly refused, but on one occasion a young and inexperienced security guard agreed, helpfully leading the group to his mausoleum and grave, along with that of his recently interred cousin, Chemical Ali. We managed a few photographs before alarm bells rang and the group were hustled away by very worried-looking officials. Further requests to visit have always been refused and, post ISIS, the whereabouts of their remains are now unknown – or, if known, remain undisclosed.

Mosul

From there we continued to Mosul, the home of Nineveh, Nabi Younis and other ancient sites, all heavily damaged by ISIS: churches, mosques, nothing was spared. Nineveh’s famous Nergal Gate, flanked by stone sculptures of winged bull- men known as lamassu, was toppled, the statues smashed and the walls reduced to just a few stones high. At the deserted museum virtually all the exhibits and artefacts have been stolen, destroyed or sold on the black market. ISIS cared nothing for the history of the country, but certainly knew how to profit from it.

There are few places left in the city that were not damaged or destroyed by ISIS. Driving through the streets there are bullet holes everywhere, churches with their steeples missing or cupolas blown up – even the mosques are devastated, the fighting spilling into them from the streets, nothing sacred. But there is hope. Builders are busy working across the city, although as always it is not easy to distinguish the half-built buildings from the half- ruined ones. One success story lies to the southeast of Mosul at Qaraqosh, the site of many churches destroyed by ISIS (burnt altars, bullet holes in the window frames, blown-up belltowers), stands the Assyrian Church of the Immaculate Conception, now fully renovated and visited by Pope Francis earlier this year.

Hatra

Situated in a gloriously isolated location across the desert sands from the bustling Mosul to Baghdad highway, Hatra is a truly unique and remarkable place. With its mix of Roman and early Arab architecture, Greek temple and Persian-style sculptures, it has a style all of its own. The first real Arab city, it was still surrounded by the ruins of its massive walls on our last visit over 10 years ago which, along with its numerous sweet water wells, enabled its inhabitants to withstand the besieging Romans for two long years without defeat. More recently, its crumbling fortifications proved no defence and it fell to ISIS and desolation, its fate unknown to the outside world.

As we approached, Hatra arose like a mirage in the desert. Her walls a little more ravaged, her buildings a little more dilapidated, but she had again withstood the onslaught of those intent on her destruction. Even the huge crane, which for many years has watched silently over the sleeping site, remained and greeted us like an old friend.

Our joy at seeing that there had been little destruction was matched by the warmth of our welcome. Italian archaeologists are working hard to clear the site and restore the damaged walls and architecture and they are enthusiastically planning further restoration and archaeological excavations.

The future?

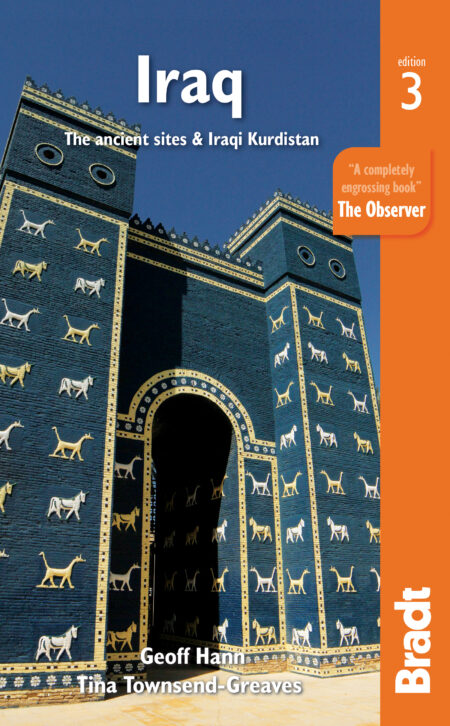

Writing Bradt’s guide to Iraq for the last 20 or so years means I have seen many changes in this country. There have been times when it has been impossible to visit – indeed, the second edition was essentially an ‘armchair traveller’s’ guide, as the start of the Iraq war just as publication happened made it a no-go area. Instead, the book became a rich read of Iraq’s glorious past peppered with tantalising hints of the treasures to be viewed when travel was once again possible.

Despite the ravages, I feel Iraq is turning a page and starting a new chapter. A new appetite for growth, visible in the plethora of new buildings springing up across the country and the opening of a new museum in Basra, is matched with a new fervour for the past and a growing local interest in the history of their country. The increase in Iraqi archaeologists working on the restoration of ancient sites, rather than their destruction, is a sign that there are greater things to come.

Travel to Iraq is never straightforward. Every year things change: in good years, new sites and archaeological discoveries open up to visitors; in bad years, sites suddenly become ‘not possible’ to visit for irrational and illogical reasons, which after hours of discussion and questions leads to the admission from our guide that he does not know the way there! Today, travel is a far cry from my early days, when a Land Rover parked in the street outside my house with a sign in the window ‘London to Kathmandu, leaves Friday’ heralded the start of another adventure across Europe, the Middle East and, of course Iraq – no roadblocks, no red tape, no permissions, just glorious drives across this most beautiful of regions.

Over the years my travels have taken me through Iran as the Shah left and anarchy reigned, through Afghanistan (including an attack by the Taliban), and along the legendary Khyber Pass, alive with feuding tribes and refugees. But through it all, it is Iraq to which I keep returning. From the early days when we travelled across the desert from Palmyra (not quite on Nairn Coaches, but traversing the same tracks) and crossed borders with Turkey and Iran, suspiciously guarded by shady characters dogging our footsteps, to more recent trips of jetting into a heavily fortified Baghdad Airport, every arrival creates the same frisson of excitement at what this trip to Iraq may hold.

More information

For more information on travel in Iraq, see Geoff Hann’s comprehensive guide: