The history of Shrewsbury Abbey is a long and complicated one.

In this article, Marie Kreft – author of our Slow Travel guide to Shropshire – dives into the past of one of Shropshire’s best churches.

The history of Shrewsbury Abbey: an introduction

Shrewsbury Abbey’s history began in 1083 when Roger de Montgomery, the Earl of Shrewsbury, vowed to turn the Saxon chapel of St Peter’s into an abbey, sending for two monks from Normandy to supervise its construction. Monastic life began in the late 1080s, flourishing thanks to the abbey’s convenient location between London and Wales, the River Severn providing a valuable means for conveying freight, and De Montgomery’s gift of the monopoly rights to three mills.

In 1137 the monastery acquired what every 12th-century monastery needed: holy relics. The remains of St Winefride were brought from Gwytherin in north Wales and interred in a shrine, attracting pilgrims, wealth and power. For insight into medieval abbey life we can read the novels of Edith Pargeter (writing as Ellis Peters), who made Shrewsbury Abbey the home of her fictional crime-solving monk, Brother Cadfael.

Fancy yourself a church aficionado? Don’t miss our guide to the prettiest churches in Britain.

Myths and legends

According to the legend, Winefride was the beautiful virgin daughter of a 7th-century Welsh prince. A nobleman named Caradoc fell violently in love with her but, not returning his passions and having taken a vow of celibacy, Winefride fled from his advances. Enraged, Caradoc chased the maiden and cut off her head, which rolled to near where her uncle, St Beuno, was praying.

At this spot, now called Holywell (in Flintshire, Wales), pure water sprang from the ground. Caradoc fell to the ground, dead, and the earth opened to swallow him up. St Beuno replaced his niece’s head on her body and she came back to life. She became the abbess of a nunnery at Gwytherin, in north Wales, and lived for another 15 years. Even Henry V is said to have visited St Winefride’s shrine in Shrewsbury Abbey in 1416, to give thanks for his conquest of France.

Although the shrine was destroyed in the 1540 dissolution of the abbey, a 13th-century stone redo survives and a modern-day Guild of St Winefride continues to pray for the abbey’s peace and prosperity.

For more Shropshire legends, don’t miss the story of the Wem Ghost.

The Middle Ages

Through the Middle Ages the abbey continued to thrive, even hosting parliaments under Edward I and Richard II. But by the reign of Henry VIII, it was in poor shape, physically and fiscally, the abbey monks turning to more worldly matters (land, property, money). Following the dissolution of the monasteries, Shrewsbury Abbey was allowed to serve as a parish church but stripped of its abbey rights and accoutrements. Furnishings, records, books, silver: all were removed.

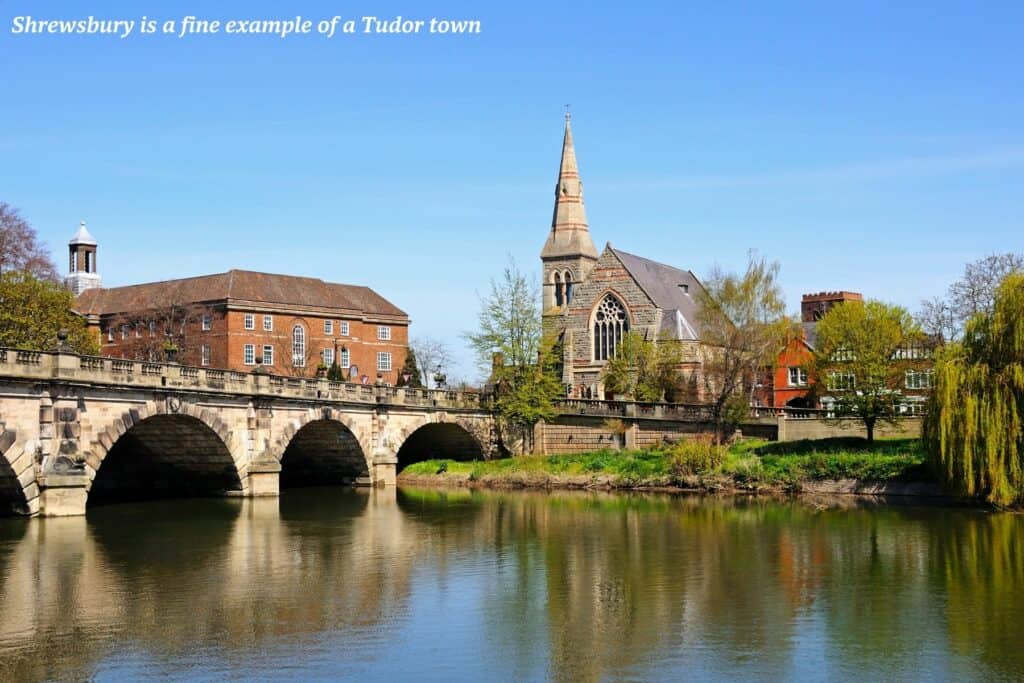

- Recommended reading: how to spend 48 hours in Shrewsbury

The 17th century…and beyond

The 17th century brought Civil War and damage to the abbey and the 18th century saw further decline. The 19th century was a period of restoration under the advice of Samuel Pountney Smith (also responsible for the church of St Mary Magdalene at Battlefield;). The Victorian era saw the advent of railway and the building of roads.

The remainder of the Norman ruins were flattened in 1836 to make way for the London to Holyhead road engineered by Thomas Telford (bringing us neatly back to that lonely refectory pulpit separated from the abbey church by a road – a victim, according to H Thornhill Timmins (1899), of ‘the exigencies of modern travel and traffic’).

More information

For more information, see our Slow Travel guide to Shropshire: