Written by Dana Facaros & Michael Pauls

The idea of an ideal, geometrically planned city has been around a long time. The ancient Persians built cities that were perfectly circular, as did the Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur, with his new 8th-century capital Baghdad. No-one really knows why they did it, and the background to the ideal cities of the Renaissance is similarly obscure.

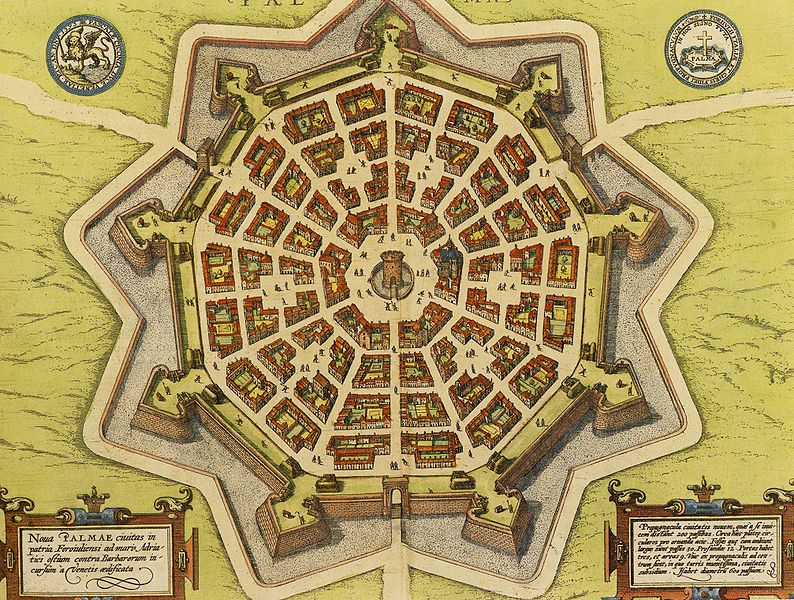

Palmanova was conceived and built by the Venetian army © Wikimedia Commons

Palmanova was conceived and built by the Venetian army © Wikimedia Commons

As exercises in perspective, Renaissance artists painted many ‘Ideal City’ views, such as the famous one by Piero della Francesca, now in Urbino. Some scholars see an influence from the cities of Thomas More’s Utopia, and at the same time Palmanova was underway, a Calabrian monk named Tommaso Campanella described a similar layout in his mystic, rather hallucinatory book called The City of the Sun.

In the 1500s, Renaissance thought collided with a military revolution, resulting in geometric cities that actually got built. Modern artillery was making old walls obsolete; the Habsburgs and the terrible Turk, both not far away, had some of the best in the world. The new fashion in fortifi cations would be long and low, spread over an enormous expanse of land to keep the city itself out of the range of the guns. The outer walls consisted of arrowshaped bastions, giving the defended place the form of a star.

Star cities are not an Italian idea, though there is another one in Italy, Grammichele in Sicily. When Palmanova began in 1593, radial fortress towns had already been built in the north of France, such as Villefranche-sur-Meuse, Mariembourg and Philippeville (the latter two now in Belgium). All these places served a dual purpose, at once settlements and fortresses. They were big enough to house an army, capable of pouring out and attacking any invader from the rear.

Palmanova was conceived and built by the Venetian army. Its design was the work of many hands, including Giulio Savorgnano, the noted, Friuli-born military engineer who built the walls of Nicosia and Candia.

A lot of thought went into it. No part of the walls was weaker than any other. The radial streets were seen as the most effi cient way of moving troops and supplies from one part of the walls to another as needed, as well as the most convenient for commerce in peacetime. Some military architects disagreed: the plan was effi cient for commerce, but a possible disaster if an enemy broke through the gates, where he would have a straight path to attack the centre. In the end, the civilian concerns of beauty and convenience won out, and the radial avenues carried straight into the central piazza.

For all the money and labour that went into this place, it was never seriously attacked. That may be the whole point. The raids of the Ottomans ceased after it was built, and Palmanova successfully protected the Serenissima’s eastern borders for almost two centuries. Sometimes a smart defence wins.

Keen to explore more of Friuli Venezia Giulia? Start planning your trip with 10% off our guide: