Written by Iain Campbell

The Abbot took our gifts of white silk scarves wordlessly. His face was wide and his thin hair was brushed over his forehead. He wore pink sheepskin boots with a cartoon figure printed on the heel. I looked at his solemn face and realised that the Abbot we were being presented to was a young child – three years old, I was told. I gazed up at him and he looked back with a constant, almost unnerving stare. Still he had not said a word. When I stared into his unblinking eyes, I saw the gaze of someone much older and the idea that he had been reincarnated and had already filled this position for two lifetimes didn’t seem so ridiculous.

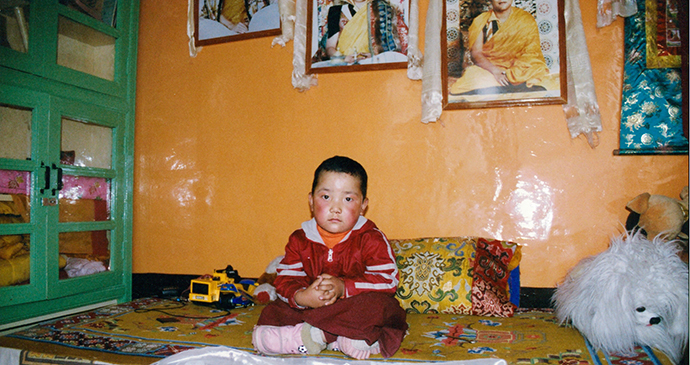

The Abbot of Mahe was just three years old when Iain met him © Iain Campbell

The Abbot of Mahe was just three years old when Iain met him © Iain Campbell

I was nearing the end of my four-month journey up the course of the Indus River through Pakistan, Kashmir and now across the predominantly Buddhist state of Ladakh. I had seen the tangled delta of the river at its mouth near Karachi and its flood plains in the Punjab, but up here the river was so narrow that in some parts I could have waded across. We drove along its course all afternoon, heading east towards its source at Mount Kailash in Tibet. The valley closed in after the city of Leh and the road burrowed into the cliffs. The rocks showed off all their colours in the high clear sun. Red scree fanned out from cracks in the mountain so that it looked like the hills had been slashed and spilled their insides. Massive boulders fallen from above were black-red and shiny, as if still showing the effects of their volcanic birth. Where the river had carved its course, the smooth cliffs were the dull yellow of ground ginger, while above the rock was sculpted into the impossible shapes of reptilian armour and burned meringues, creased with cracks and faults.

We passed teams of road builders. Theirs was a purgatorial task. The first team collected rocks and laid them in piles 30ft apart along the road. The second team followed and broke up the rocks into chips that were then used to make the road bed. I had seen this done in Pakistan with a diesel-powered stone breaker, but here it was done by migrant Nepali labourers with hammers. They were wrapped in layers of clothing, hats and turbans of scarves but still they looked freezing, keeping their elbows close to their bodies and their heads down to keep out the draughts. For several more miles the piles of unbroken rocks continued. It looked like there were many years of work still to go. Finally, in the late afternoon, we had reached a bridge at Mahe beneath this isolated monastery, and curiosity had driven me uphill to its doors.

As I was putting on my shoes in the atrium I looked up and saw that the tiny Abbot had come to his door to watch me leave. He tottered across the floor with his toddler’s gait and stared with that unashamed curiosity that children of that age have. This was the beginning of his third lifetime in the monastery, and more lifetimes would follow them in these small rooms high in his white, wind-whipped palace. The cycle stretched on and on like the geometric whirls of rivers on the thangka, the silk paintings that decorated the walls of the temple, re-circulating, unstoppable, even by death.

Outside, some of the young monks, aged eight or nine, were cleaning the steps of the prayer hall. They jostled as they worked and tripped each other up with their mop handles. A stooped old monk shouted at them, but when he had gone they giggled. When they got older, many of them would leave the monastery; when they reach their late teens, monks are allowed to choose whether they want to spend their adult life there. The prayer hall steps were visible from the Abbot’s window, but he would never walk on them – he was bound to stay in the monastery forever.

I wondered whether it was fair to have the same person in charge all the time, whether he would get jealous of the boys who were not as important as him. While it was undoubtedly a privileged position to hold, for a moment I felt sorry for that little solemn boy with all his lives stretched before him like piles of rocks.

Read more of Iain’s journey along the Indus River in his book, From The Lion’s Mouth: