Written by Iain Campbell

We paused after a deep river crossing to empty our shoes. It was getting dark, we had been walking for ten hours and Bachshar was getting worried. ‘No-one walks at night. It is dangerous, but unfortunately we must go on because I told the police that you would be back today.’

I had made my plans fairly well known in the roadside village of Dandai, so I shouldn’t have been too surprised to find that they had filtered back to the police station. I had chosen not to register officially because I was concerned they would prevent me from going.

‘It is not good to walk at night. Only robbers and bad men walk at night. There are dogs and the farmers will be scared. Stay close and walk quietly.’

After the stifling heat of the day, a strong wind was now bending the trees and far away I could hear the muffled bass of a storm. The wind blew the rain in quickly and we pulled our blankets over our heads and stumbled on. In some ways the weather was useful, as the dogs were less likely to hear or smell us over the storm. Very soon I was completely soaked and my blanket lay in heavy folds around me. Bachshar’s beard was drenched and stuck together in strands like seaweed.

It had been over a month since I had started my journey following the course of the Indus River through Pakistan and India to the Tibetan plateau. For hundreds of miles I followed its broad lazy meanders on the plains of Sindh and the Punjab, but now I had arrived at the mountains in Kohistan district where the river cut through steep ravines and thundered against the cliffs of the Karakorum foothills. The British had called this area Yaghistan, ‘Land of the Ungovernable’, and it had remained an area of weakly controlled territory throughout the colonial period. It had also caused strategic problems for Alexander the Great who found his great sweep eastwards delayed by the people and geography of Kohistan, whom he was only able to subdue after a lengthy siege and massive earthworks to get around the mountain fortifications.

Bachshar was a local merchant and had agreed to guide me to the top of Pir Sar, the naturally fortified mountain stronghold where over 2,000 years earlier the inhabitants had resisted Alexander’s advance. For most of my journey I walked alone, but as tensions remained in Kohistan, I had been advised to take a guide.

Three hours of walking up steep cultivation terraces brought us to the broad, grassy plateau where cows and goats were being pastured. Bachshar called out to a man sitting silhouetted against the sky. He stood up and walked to us. He was tall with an aquiline nose and a twirled Salvador Dalí-like moustache. He carried a Kalashnikov that had been elaborately decorated on the butt with patterns of stamped metal. His skin was darker than Bachshar’s because he was a Gujar, one of the original Dardic clans that herd animals on the highlands of Kohistan.

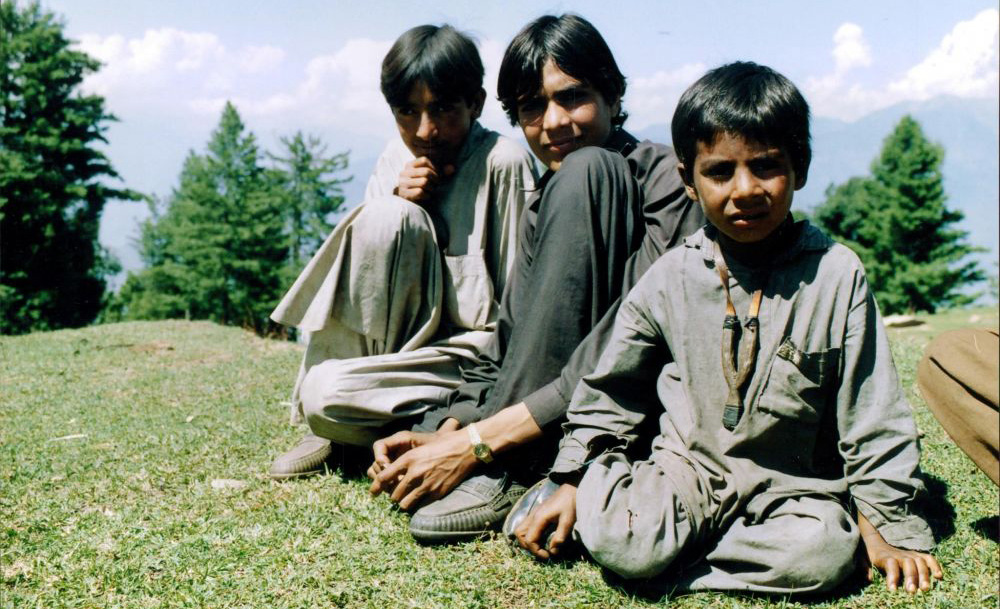

The Gujar now accompanied us along the ridge. The cows had cropped the grass bowling green-short and children ran among the animals playing with homemade catapults. All the men we passed were armed, most with antique-looking rifles –although a few of them had automatic weapons. Today, as in the past, these lands are well defended.

The ridge narrowed to a rocky slope. We climbed over boulders and across fallen pine trees and finally reached the crumbling walls of the old fort. The land dropped away on every side and it was clear how immense the task was that faced Alexander the Great when he tried to conquer the land of the ungovernable. Indeed, his army would fight onlyone more battle in his Indian campaign before his troops demanded he turn home.

In the end, it was the hospitality of the Kohistanis that made our journey difficult. As we descended in the late afternoon, the farmers were back from the fields and at almost every house we passed they demanded we stop for tea and this slowed our progress dramatically. It was only darkness and rain that allowed us to push on, but they brought their own problems. It was a relief when we finally saw the lights of the roadside village below us. We stumbled awkwardly down the scree that led to the truck-stop hotel where we dried ourselves as best we could, and ate bowl after bowl of dal mash and chapatti. Trucks normally drove through the night and gave the hotel plenty of visitors, but in heavy rain rock falls were likely, and the highway would be quiet for the night.

Read more of Iain’s journey along the Indus River in his book, From The Lion’s Mouth: