The ‘Land of Fire’ is a strange moniker for a place that’s home to one of the world’s largest extra-polar ice sheets. Swathes of ice flow down from the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, calving off into stormy seas and pooling into still lagoons. According to one Chilean guide I met, ‘In Patagonia, you’re almost always standing on a glacier.’

Like most first-time visitors to Patagonia, it was the dramatic landscapes that drew me there. Setting off from Punta Arenas in Chile, I backpacked my way through the national parks on either side of the border with Argentina, taking buses that zigzagged back and forth from Los Glaciares and Perito Moreno on one side, to Torres del Paine and Pali-Aike on the other. And, as expected at the pointy end of South America, there were vistas of glacial ice and snow-tipped Andean peaks at every turn.

A good couple of months to hit the trails also allowed for lazy days and the important business of ice (well, ice-cream scoffing in Argentina, to be specific). It felt like I was experiencing it all, from trekking the Torres del Paine W route, to horseriding to view the summit of Cerro Fitz Roy and donning crampons to climb over the ice at Glacier Viedma. As the trip wore on and the cold and the ice filled my every waking moment, the desire to look into the origins of fire became less pressing.

Like many travellers who venture to Patagonia, I didn’t see much of Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tail of the continent, beyond the town of Ushuaia. After all, there is a lot of land to cover down there and even two months can’t do it justice. The parks are many hundreds of kilometres apart, and the Andean terrain makes journeys by road even longer.

On subsequent visits though, I’ve had time to venture further southwest – and pick up my quest to search for the fires. Chile and Argentina share the main island of Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, but the larger part of the archipelago exists to the west of the border. Those Chilean fjords and innumerable islands make up the expanse of Chile’s southwesterly national parks – Alberto de Agostini and Cabo de Hornos, to name but two, well known for their remote and windswept allure. The best way to get to them is by sea.

A journey through the fjords

At the start of 2020, I joined a small-ship expedition with Chilean-owned Australis to navigate the Fuegian fjords. And still there was no upward change in the temperature, and no obvious explanation for the fire metaphor. From the abundant hanging glaciers viewed from the deck of the ship, to tidewater glaciers like Garibaldi and Águila, it was pretty clear from the worsening weather and our latitude that after Cape Horn, the next port of call was the deep freeze itself – Antarctica.

It might seem that much of the exposed and often inhospitable Tierra del Fuego archipelago is too harsh for human settlement – that if trees need to bend with the wind to avoid snapping, then people might be better off in more temperate climes. And though most of the archipelago is now uninhabited, during expert on-board lectures by Australis expedition leaders, I learned of a time before conquistadors and buccaneers, when humans lived in ways we can only imagine.

And that’s when it all fell into place. Most of us know of human endeavours in the region through the exploits of men such as Charles Darwin and Robert FitzRoy. They voyaged here on the HMS Beagle in the 19th century, mapping the area and taking samples to further the cause of naturalism and maritime cartography. The region’s nomenclature pays homage to their explorations, from the Beagle Channel to the Darwin Mountain Range.

And 500 years ago, it was the indomitable Portuguese adventurer, Ferdinand Magellan, and his expedition ships, searching for a sea passage that would shorten the journey along the competitive spice trade route, while circumnavigating the globe. Magellan’s name is similarly set in stone here – literally on the plinth of his bronze statue in the main square in Punta Arenas – and in the natural world, from the area’s diminutive penguins to an entire Chilean province and the now famous Strait of Magellan.

But far from stumbling upon an uninhabited world, Magellan’s men did what most explorers had done before them, and laid Western eyes on lands that had already been discovered. In fact, one of the first things that greeted them in 1520 was the smoke from large fires that emanated from the settlements of indigenous groups, lit to attract traders from the north, according to my Australis guide.

Finding the fires

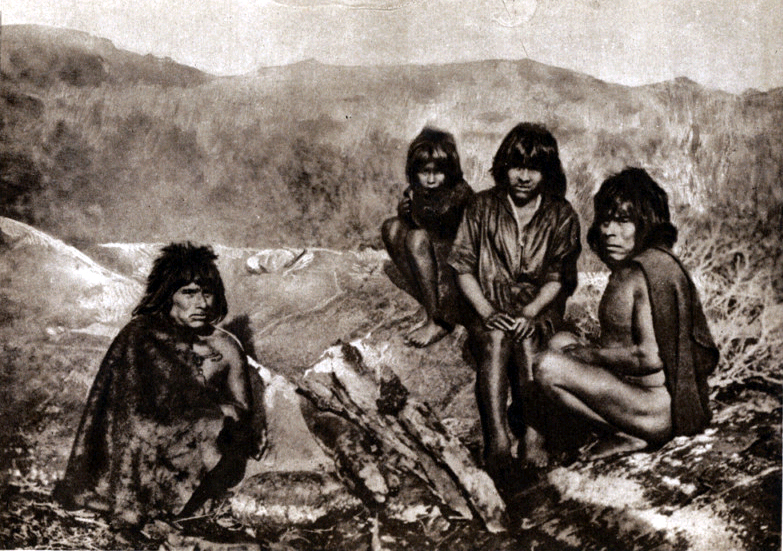

The Yagan, also known as the Yámana, are the world’s southernmost indigenous peoples. From the main island of Tierra del Fuego, to the tempestuous seas around Cape Horn and Onaašáka, or the Beagle Channel, as we now know it, they’d been living as sea-faring nomads for thousands of years before Magellan’s arrival, with archaeological sites in the region dating to 11000bc. In large canoes made from local coigüe or Nothofagus trees, they kept permanent fires smouldering on beds of sand and mud. Always naked, but using animal oils and fats, and trading in skins and furs, the Yagan used fires to quickly dry and warm themselves. When they moved into simple structures on land, they took the fires with them, these eternal flames being central to their survival.

And so it became Tierra del Fuego when it might so easily have been Tierra del Hielo, had Darwin been the one to name it. He wrote in his notebook: ‘It is scarcely possible to imagine anything more beautiful than the beryl-like blue of these glaciers, and especially as contrasted with the dead white of the upper expanse of snow. The fragments which had fallen from the glacier into the water were floating away, and the channel with its icebergs presented, for the space of a mile, a miniature likeness of the Polar Sea.’

I tried to imagine what this must have looked like to Magellan’s men, with the hundreds, even thousands of flames of small communities glowing against the glacial blues and whites. The vivid fires, reminiscent of their own hearths and homes, would have perhaps been more striking to a homesick sailor than the inhospitable ice.

There were other groups in Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia too, from the Tehuelche and the Selk’nam to the Ona and the Kawésqar, some venturing further into the mainland for sustenance and shelter. But it was the Yagan, being seafarers, who were the most successful living along the coast. While the women rowed and dived naked into icy waters to forage and fish, the men hunted seals with 3m-long harpoons, constructed with detachable bone spears. At Wulaia Bay, there’s a small museum that pays homage to the largest Yagan settlement.

The usual story of zero resistance to Western diseases, dispersal and genocide saw each thriving indigenous group largely decimated, despite having survived there for thousands of years prior to European settlement. Now reduced to a small village, Ukika, near the naval town of Puerto Williams on Isla Navarino, the last-remaining local descendants of the Yagan have tried to keep their language and their ancestral stories alive, making audio recordings and giving language lessons. In the slim volume of transformation tales, Hai Kur Mamášu Čis (I want to tell you a story), sisters Úrsula and Cristina Calderón passed on the stories that were told to them by their grandmothers. From cormorants and penguins to the ice and rocks of the landscapes, Yagan tales, like the indigenous Australian Dreamtime stories, all relate human existence to the natural environment.

The Yagan believe that there are spirits in the ice and that looking directly at a glacier is to be avoided, telling transformational tales of girls becoming birds. The book tells us that these stories ‘take place below the same sky and over these same waters, in giant voyaging canoes and around eternal fires and on immense mountains. A landscape which has always been open to the passage of humankind…’ Although Magellan didn’t colonise Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, he set the course for the colonisers responsible for the demise of the Yagan people’s nomadic way of life. Úrsula has since passed away, leaving Cristina as the last full-blooded Yagan woman in Chile, and the only person to remember fully her language and ancestral stories. The coastal fires of nomadic groups have long been extinguished, leaving just the glow of electricity from Puerto Williams and Ushuaia, alongside the legacy of the seemingly incongruous but very significant name – the Yagan Land of Fire.

About Nori Jemil

Nori Jemil is a UK-based award-winning photographer, writer and videographer, specialising in travel. She is also the author of Bradt’s recent book The Travel Photographer’s Way: