Planning a future trip to Uzbekistan? There are plenty of ways to familiarise yourself with the country and its culture before you visit. Here’s our pick of the best:

To read: The Devils’ Dance by Hamid Ismailov

Uzbekistan’s literary canon is a reflection of its diverse linguistic and cultural heritage. In addition to writings in Uzbek, some of the finest works of Persian/Tajik literature were written in Samarkand and Bukhara, and in the 20th century writers seeking a Soviet Union-wide audience for their work were compelled to write in Russian.

Uzbekistan has a number of contemporary writers, though few of these are known outside the country as their works are rarely available in translation. Hamid Ismailov, however, has lived in Britain since 1992 and has produced many fine novels. His most notable work is The Devil’s Dance (2016), a book about Kadiriy and the other writers shot by Stalin, and supposedly the first novel to be translated from Uzbek into English; it won the prestigious EBRD Literature Prize in 2019.

To listen to: shashmaqam music

Uzbekistan is widely considered to have the most diverse range of musical styles in Central Asia. The classical style of shashmaqam, now widespread across the region, is believed to have developed in the cities of Bukhara and Samarkand in the pre-Islamic era. The term refers to the structure of music with six sections in different musical modes.

This style is similar to classical Persian music and is often in terspersed with devotional Sufi poetry. This lyrical, deeply spiritual music is usually accompanied by stringed instruments like the dutor, tanbur, sato and ghizhzhak. Shashmaqam music was placed on UNESCO’s list of the world’s intangible heritage in 2008, and there’s a good supply of fine young musicians from the State Conservatory in Tashkent.

To cook: plov

It sometimes seems that Uzbekistan runs on plov, the heavy, calorie-laden dish that is the nation’s undisputed favourite (and also features on UNESCO’s intangible world heritage list). Here’s how to make it (serves 8).

Ingredients

- 1kg of lamb shoulder, separated from the bone and cubed

- 1kg paella rice

- 250ml sunflower oil

- 1kg peeled carrots cut into 1cm lengths

- 3 whole garlic bulbs

- 3 medium-sized onions, sliced thinly

- 1 tbsp cumin

- pinch of salt

- 2 chillies (optional)

- You will also need a 5-litre cooking pot.

Method

- Wash and soak the rice in cold tap water.

- Heat the oil in the cooking pot over a high flame and deep fry the meat until it is golden brown. Take the meat out and put to one side.

- Fry the onions until they are golden and then add the meat again, as well as the carrots. Heat for 20 minutes (stirring frequently) or until the carrots are soft and slightly caramelised. Add the cumin.

- Reduce heat and add water to cover the carrots and meat. Leave it to gently simmer for 1 hour, or until most of the water has evaporated.

- Place the whole bulbs of garlic and the chillies (if using) on the top of the meat and carrots.

- Add the rice that has been soaking on top of the meat and carrot layer in the cooking pot, and then cover contents with 2cm depth of boiling water. Boil it gently until the rice has completely absorbed the water. Be careful it doesn’t burn on the bottom.

- Reduce the heat and cover the pot with a lid. Allow the plov to steam for 20 minutes. If you think it might be catching, remove it from the heat entirely.

- Remove the garlic bulbs and chillies and put them to one side. Don’t stir too much – the plov should be served upside down, ie: with the rice on the bottom, vegetables in the middle and meat on top, on a large communal dish, and decorated with the garlic bulbs and perhaps quail eggs, herbs and spring onions.

- Enjoy with a tomato and onion salad, flat bread and a pot of freshly brewed tea.

To create: traditional tile patterns

Tiles must be the most impressive of Uzbekistan’s decorative mediums, and tile making reached its peak during the Timurid era. Soft clay tiles were individually carved, painted, fired and glazed, their colours derived from ground lapis lazuli and turquoise, yellow ochre and burnt sienna, terra verde and red iron oxide. Similar techniques have been used to produce a variety of plates, bowls and other homeware items, which are popular and affordable souvenirs for visitors.

If you’d like to learn more about the patterns that adorn the tiles you’ll spot in Uzbekistan, and have a go at recreating them for yourself, Samira Mian offers a pattern tour of the country on her website. Her four lessons focus in turn on patterns found in Bukhara, Khiva, Samarkand and Tashkent.

To learn: Central Asian dance

There are two main types of dance in the Uzbek tradition: folk and classical. Some folk dances are reserved for special occasions, while others are impromptu expressions of joy. Classical dance is primarily the domain of women; lyrical upper body and hand movements, facial expressions and empathy with the music characterise performances.

Fancy learning the art of Central Asian dance yourself? On her YouTube channel Nilofar Dadikhuda has a series of videos that aim to do just that. The first lesson teaches you the basic necessities, before progressing into choreography and simple dance routines.

To watch: a traditional sporting match

Traditional sports include kupkari, a sort of prototype of polo in which teams (theoretically of six on each side, although there can be hundreds) compete to seize a headless goat’s carcass and throw it into a kazan – a round structure of brick, concrete or truck tyres.

One event where traditional sport can be seen in action is the World Nomad Games, which also features eagle hunting, dog handling, intelligence games and various cultural displays. The biennial event was first held in Kyrgyzstan in 2014; at the 2018 games Uzbekistan came fifth in the final medal table, taking home 33 medals, indlucing a silver in kok boru (a horseback sport similar to kupkari). Check out the video above to see the Uzbek team in action.

More information

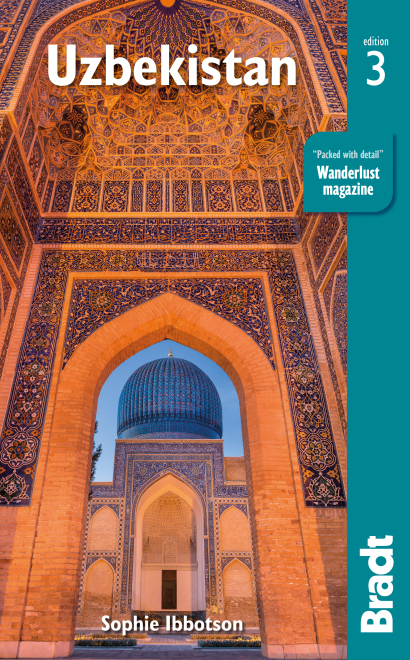

Inspired to plan a future trip to Uzbekistan? Check out our guide: